What do our minds sound like? Every day they fill with running internal dialogues of which we are largely unaware. These are constant and repetitive thoughts, whirring like wheels and dripping like interminably leaky faucets. In their individual bodies of work, John Giorno and Christine Sun Kim become aware of these private voices and ponder how external social forces shape their public expression. Their graphic work is simultaneously minimalist and sumptuous, bursting at the seams from the effort of resisting the narrow self-definitions these dialogues impose.

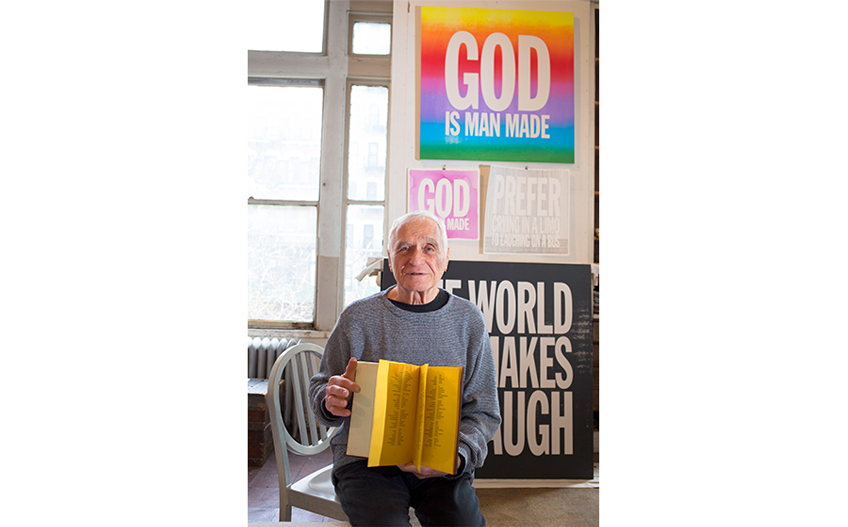

Giorno’s canvases revolve around words, which emanate from the paintings’ centers against bright rainbow or monochromatic backgrounds. The phrases are short and pithy, proclaiming: “BIG EGO,” “GOD IS MAN MADE,” “YOU GOT TO BURN TO SHINE.” They resound in your brain. Giorno draws these words largely from his own poetry, which in turn draws text from the mass media and common culture.

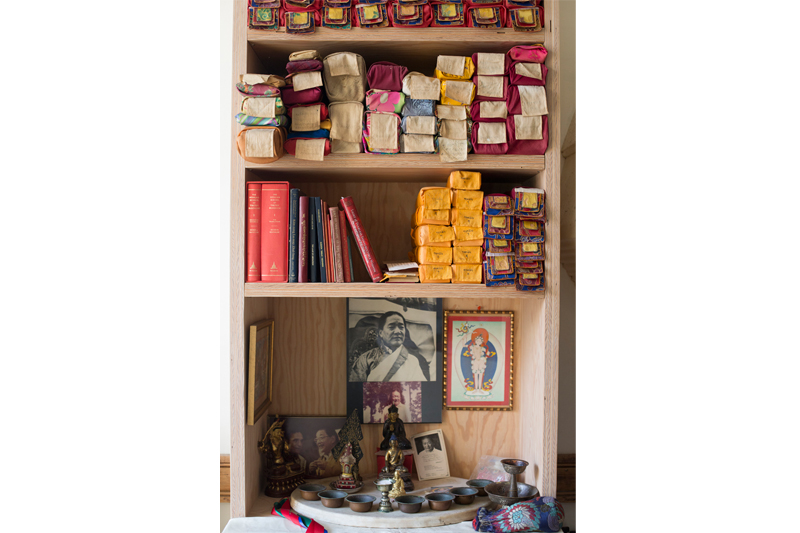

Giorno’s poetry, in earlier incarnations, contributed to the genre of “found” or “cut-up” poetry, which appropriated texts from newspapers and other sources. Giorno’s flat surfaces and confrontational, yet seemingly generic typeface (he actually developed the typeface with a designer) continue to allude to mass-produced poster advertisements, many of which use catchy slogans that bombard and control the consumer in daily life. Even if the texts of his more recent paintings are not official examples of his “cut-up” style, they are components of an immense graphic archive””from the 1980s onward, Giorno created hundreds of similar or nearly identical poetry-slogan paintings silk-screened on canvas. Their messages also index Giorno’s commitment to Tibetan Buddhist practice. For decades the artist has hosted numerous Tibetan Buddhist lamas and held ceremonies at his loft on the Bowery in Manhattan, which contains an elaborate shrine room. Each painting may be read on its own as a mantra, which when repeated, has the potential to transform the reader’s mind and to loosen the ego’s hold. In an introduction to Giorno’s poetry book You Got to Burn to Shine, the renowned Beat writer (and Giorno’s former housemate) William Burroughs describes the effect of Giorno’s repeated phrases, writing that they “break apart the too familiar “˜meaning’ of the words, to crack them open and show their emphasis. This explicit realization conveys a feeling of liberation.” In public poetry performances, Giorno accentuates his repetitive verse with changing volume and pitch to achieve similar effects, building into a fiery energy he has likened to a Tibetan Buddhist heat-generating meditation practice called tumo.

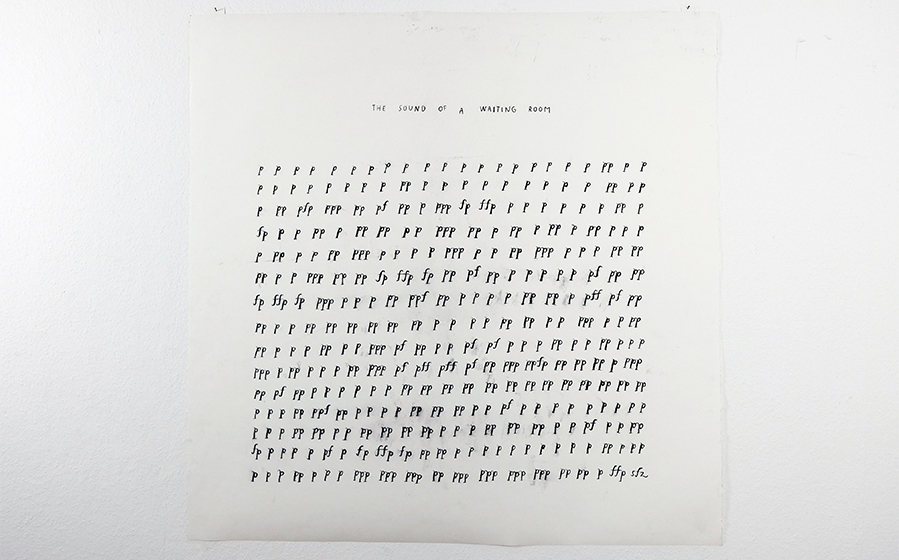

Similarly Kim’s drawings use strategies of repetition to break apart familiar meanings, but instead of deconstructing words, she deconstructs the politics of sound. Musical notations known as dynamics””originating in European classical music to indicate the relative loudness of a note or phrase””fill the paper in successive lines, forming constrained and irregular grids. Collectively the dynamics in each drawing communicate the frequently playful central titles. In The Sound of a Waiting Room, the first two lines contain an orderly sequence of piano (p) markings, meaning soft, and a couple of pianissimo (pp) notations, meaning very soft. We are in a waiting room filled with complacent individuals leafing through Time and Women’s Health magazines. In the following lines they grow impatient, perhaps one checks in again with the receptionist (forte piano, fp = loud then soft), while another is visibly agitated (fortissimo piano, ffp = very loud then soft). Others fall more silent in embarrassment (pianississimo, ppp = very, very soft), and so on. The last dynamic on the paper is the loudest and most abrupt change (sforzando, sfz = with sudden emphasis): “The doctor will see you now!” In her composition Kim’s sounds are anthropomorphized, each exuding an individual personality only understood in relation to another. But sounds in this setup are inaudible and, rather, refer to their behavioral dimension. Ultimately Kim, who was born deaf, enables the hearing viewer to participate in the same mediated experience of sound that she does, de-familiarizing the process of hearing itself. For Deaf audiences the drawings are accessible and poignant; while Kim says that she often does not have a Deaf or hearing audience in mind when making drawings, she has observed that in her encounters with other members of the Deaf community they have not needed explanation to understand her work.

Kim frequently has stated that her art practice “deals with socially informed ideas surrounding sound” and attempts to unlearn sound etiquette and challenge “vocal authorities.”1 For Kim the audible and cochlear dimension of sound is shaped by others, including American Sign Language (ASL) interpreters, subtitles on television, texts on paper, and digital media. Because of this she is particularly attuned to the social politics of sound, and her drawings are a score for listening. She repeatedly has referred to hearing people as her “speakers” for transmitting bits of sonic information. Many of her graphic and performance works focus on the musicality of ASL and, by extension, all spoken language. In Face Opera ii Kim composed a score of emotions presented in sequential text on an electronic tablet , which the conductor (sometimes Kim herself) displays to a choir of pre-lingually Deaf people. The choir performs the score by using corresponding facial expressions and body movements, drawing attention to these expressions that qualify nuances of speech and language. ASL is music in which each component, such as a hand movement or facial expression, comprises a chord in a composition.

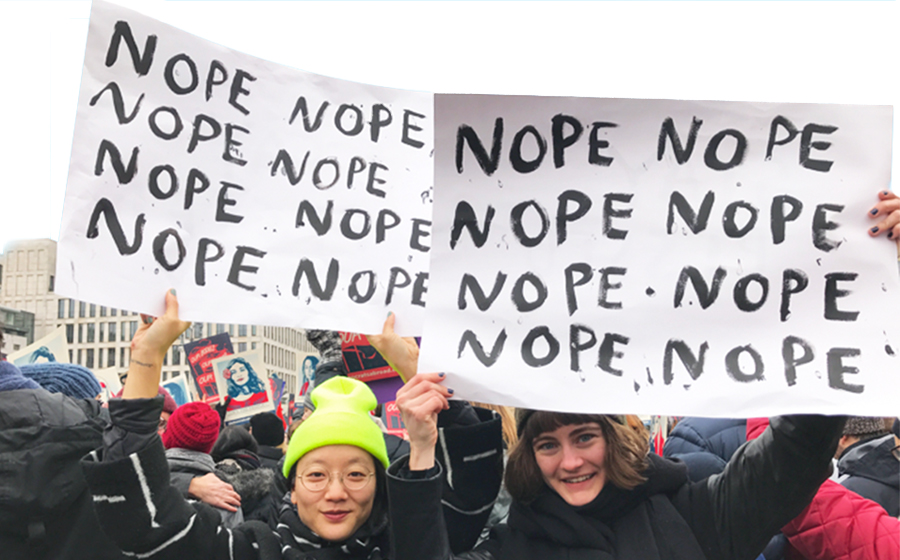

Just as Giorno and Kim’s graphic works may be read as extensions of their performances, they also gesture to the artists’ political activism. Giorno’s poetry-slogans share the aesthetic of protest signs, perhaps alluding to the artist’s well-documented participation in Vietnam War protests and his lifetime advocacy of gay rights. Kim’s work advocates for a broader definition of listening and for marginalized ASL communities. As much as the artists question the politics of voice, their work collectively communicates an optimistic message about the potential of voice to transform our inner and outer worlds.

About the Contributor

Risha Lee is a curator for the Rubin Museum who was born in Oakland and is now based in Brooklyn. She earned a BA with high honors from Harvard College and a PhD in Art History from Columbia University. Her work has focused on artistic connections and encounters that traditionally have fallen under the rubric of Asian art but defy easy categorization. She has taught a variety of art history courses at Columbia University and the American University of Beirut.