In this blog post, Fabiana Weinberg, Exhibition Designer for Monumental Lhasa: Fortress, Palace, Temple, explores the qualities of monumental representation. She traces how images are constructed, heard, and placed. Read her reflection below and visit Monumental Lhasa to see Fabiana’s work in person.

Exhibition curator Natasha Kimmet holds up a postcard of the Potala Palace, a main monument located in Lhasa, Tibet. In one of our first staff meetings to discuss the exhibition Monumental Lhasa: Fortress, Palace, Temple, the simple gesture—postcard held high while indicating, this is the Potala Palace— made the point clear: an image of a monument can stand in for the actual place, even when one cannot visit. Immediately, sites visited as image, via a postcard, publication, online search, photograph, or painting, come to mind. Dissemination of images is part of how we see and how we experience. Furthermore, the images themselves, and what they reveal through looking, such as the maker, the individual who commissioned the work, the selected medium, the context in which it was created, the chosen view, and the purpose of the image, tell us even more.

Constructing Monuments

As a student of architecture, representation through image making is fundamental to my work. Architects rely on a set of tools, drawings, renderings, and models, to communicate a full-scale structure. The process requires abstraction: reflecting on the main qualities of the building and then deciding how best to communicate them. To heighten the imposing nature of a structure, the rendering may present a perspective that looks up at the building, or, its surroundings may be represented proportionally smaller. To communicate that a building is light and airy, it may be modeled out of translucent materials. There is an intention to materialize specific motivations or qualities. Once the work is made, it is then required to stand back from it and see if this is achieved.

Hearing Monuments

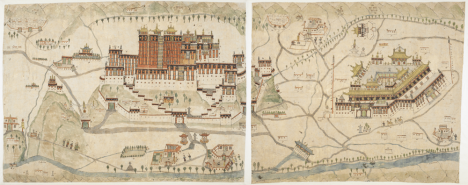

My graduate thesis advisor would say that once an image is made, stand back and listen to it. Listen because the work is an active participant; it has something to say. One may have certain intentions in the making, but the image, the thing created, becomes autonomous. We must be open to what it says back to us. It is not unlike listening to the images in Monumental Lhasa. In one painting of the Potala Palace and Jokhang Temple, the entrance facades of both structures face the viewer, a spatial relationship that is not actually experienced (an accurate mapping would rotate the entry of the Jokhang Temple so that it faces the Potala Palace, not the viewer). But accuracy is not of primary interest here. Instead, the painting is offering an invitation to enter, it is saying, “See the most impactful and recognizable facades of these monuments.” Imagined relationships become real qualities. By noticing these details we have started to listen to the painting’s story. And there are many stories that require listening in Monumental Lhasa.

Placing Monuments

In the galleries, a vast sky is created along the outer blue walls where these monumental views have gracious space to reside; space for each to have autonomy. Objects of various media, including photography, painting, drawing, watercolor, printed material, and film are juxtaposed and immediately visible when stepping onto the gallery floor, highlighting the various “tools” that tell the story of this place.

The central green-walled space provides solid ground on which vintage View-Masters are staked looking upward toward another sky, the Museum’s oculus, illuminating views of Lhasa over time. As we look up through the viewer with nostalgia, thinking back to all the images of place we have made, seen and experienced, time and place collapse as we are transported through image.

Images surround us; stand back, or look up, and listen.

Continue listening to these images in Monumental Lhasa: Fortress, Palace, Temple during your next visit to the Rubin.