How wargs and tulkus master their consciousness

This post is part of a series exploring the connections between Game of Thrones and the dynamics of power in the world of Tibetan Buddhism. Warning: spoilers from seasons one through seven lie ahead.

Nothing in this world is more universal””or more final””than death. We try to avoid or delay it, yet it has complete power over us. Or does it? Many religions espouse the belief that the faithful can gain power over death through resurrection or reincarnation.

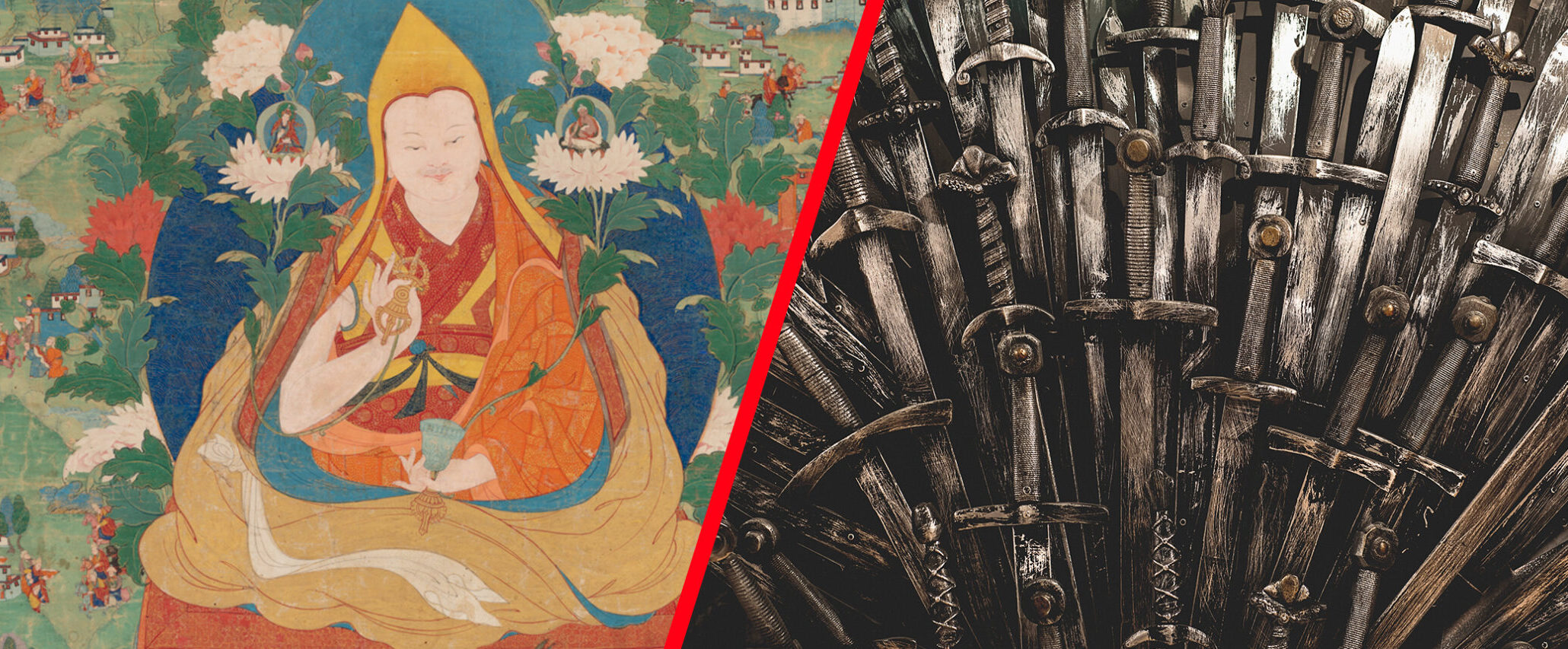

Fictional narratives similarly explore the idea that death is not the end. Characters may die only to return later, or they find ways to separate their minds from their mortal bodies. George R. R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire novels and the Game of Thrones television series are filled with such twists. They also share remarkable parallels with ideas in Himalayan religions pertaining to multiple lives and the transfer of consciousness outside the body.

Religion and the Transcendence of Death

In Western culture, we are familiar with the Christian belief that Jesus was resurrected from the dead, and Christianity, Judaism, and Islam all foretell that God’s Last Judgement will deliver the dead to eternal bliss or eternal punishment.

Adherents of Himalayan religions likewise do not believe death is the end, but rather than an afterlife they believe in reincarnation. All but the most spiritually advanced beings die and then return to this world in another form. Buddhists and Hindus want to escape the endless cycle of rebirth, suffering, and death called samsara. Without control over the karma that shapes one’s destiny, rebirth is not power over death but subjugation to it.

Reborn Lamas and Sinister Yogis

On their way to Buddhahood, bodhisattvas overcome the prison house of karma and gain greater and greater mastery over life and death. Buddhas are beyond life and death but can manifest emanation bodies (nirmanakaya) to help mortal beings. The Tibetan term tulku refers to lineages of honored religious masters like the Dalai Lamas who can compassionately reincarnate to carry on their teachings and benefit all. The painting Scenes from Life of the Fifth Dalai Lama, currently on view in the Rubin’s exhibition Faith and Empire: Art and Politics in Tibetan Buddhism, depicts Avalokiteshvara descending into the Dalai Lama’s palace, showing that the Dalai Lama is an incarnation of this deity.

The ability to direct one’s consciousness at the time of death is a goal of Hindu and Buddhist yogic practice. One skilled in the Tibetan practice of phowa, or transference, can direct their mind through the skull to a pure land where Buddhahood is easy to achieve. Powers of this kind are not always used for good. Stories of sinister yogis in Tibet and South Asia tell of sorcerers who take over other people’s bodies, raise the dead, and create zombies.

Resurrections and Skinchangers

Game of Thrones is notoriously ruthless about killing off its characters, heroes and villains alike, but they have a way of returning. Beric Dondarrion repeatedly comes back from the dead by the magical intervention of a Red Priest, and Jon Snow similarly cheats death through the rites of Melisandre. No one returns to life entirely the same. In the book series, Catelyn Stark is “resurrected” as Lady Stoneheart, but she does little but croak out words demanding vengeance against the Lannisters. According to the Lord of Light religion, the ancient hero Azor Ahai will be reborn to fight the forces of darkness once more, and Melisandre has tried to identify his reincarnation.

The wargs are more like South Asian yogis of legend, with the ability to mentally enter another body. Brandon Stark, for instance, can take over wolves, birds, even the stable boy Hodor. Warging is a congenital ability, but it is dangerous and requires training. A skilled warg can use this power to escape death, as with a wilding who entered an eagle when Jon Snow killed his human body. Although this act is reminiscent of Buddhist reincarnation and phowa practice, it is not permanent, and the warg will eventually lose his or her consciousness inside the mind of the beast.

The Finality of Death

There are striking parallels between Game of Thrones and Himalayan religions in the way advanced practitioners can manipulate their consciousness to transcend their bodies or even avert the finality of death. One aspect of Himalayan philosophies that does not appear in Game of Thrones is salvation from the powers of death. Whether or not you believe it’s possible to gain such control over death, these stories appeal to the faithful and skeptical alike.

Take a special Game of Thrones tour of the Rubin Museum and learn more in the exhibition Faith and Empire: Art and Politics in Tibetan Buddhism, on view February 1-July 15, 2019.

About the Contributor

William Dewey is a curatorial fellow at the Rubin Museum. He recently completed a PhD in Tibetan Buddhism from the University of California, Santa Barbara, and spent a year teaching at the Rangjung Yeshe Institute in Kathmandu.