As much as we’d like to think we’re in charge of our lives, the earth’s natural forces can disrupt our thoughts, emotions, and livelihood. A violent storm can destroy a mood”¦or even a home! City-dwellers often grow to dislike the rain, considering it to be an annoyance at best.

Why do we so often antagonize the weather—and is there another way to relate to the earth’s natural forces?

Monsoons in Himalayan Culture

The monsoons can seem like incredibly wild and destructive forces, but in South Asia, torrential downpours are often greeted with great enthusiasm. Imagine that reaction from New Yorkers! While these rains can certainly be intense, the people of India and Nepal have not only learned how to live with downpoursbut actually depend on them for growing and harvesting rice. For them, the rain storms are seen as a return to life after the desolate pre-monsoon season and are celebrated in different facets of life.

Godly Waters

In India and Nepal, the rivers are often portrayed as godly. The most famous example is the Ganges River, which people worship like a goddess in its own right. According to Gautama Vajracharya, curator of the Museum exhibition Nepalese Season: Rain and Ritual, all bodies of water are associated with the “feminine divine.” That makes the sky a goddess as well since it holds the waters necessary for all life below. From this perspective, every drop of rain is a blessing!

The Sky is a River

Monsoon rains fall so powerfully, it would be easy to imagine them as river waters flowing down from the sky. In fact, natives of the Kathmandu Valley traditionally believed that the same animals found in a river could also be found in the sky.

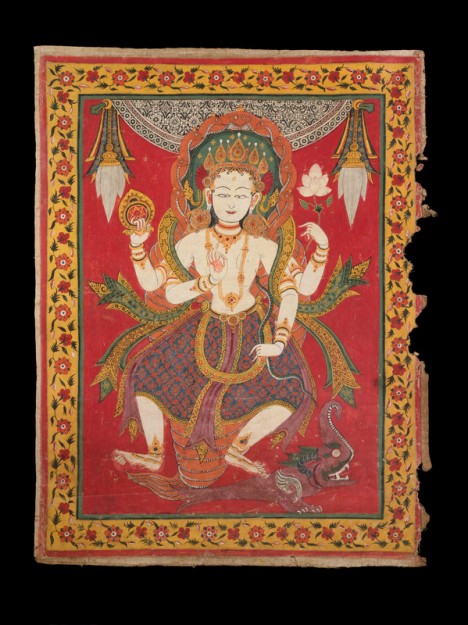

We can see this idea represented in Nepalese art. The 19th-century torana from Nepal, pictured above, used to be a gateway to a temple. At the peak of the torana sits a kirtimukha, or “face of glory,” which Vajracharya interprets to be that of a lion—a common symbol of the sky in Newari culture.

Looking closely at the details, you can see other creatures emerging from the “cloud foliage” in the background: the kirtimukha holds two snakes in his mouth, animals often associated with subterranean levels and water; further down at the base of the torana there’s a pair of makaras, mythological aquatic animals with the trunk of an elephant, the head of a crocodile and the body of a fish.

The use of these various animals together in a single work of art demonstrates how the Newari people so closely related the sky with the waters of Earth. Vajracharya even remembers his grandmother teaching him how to look for these river animals in the heavy and dark pre-monsoon clouds—adding to the celebration and wonder of the monsoon rains.

The art of the Kathmandu Valley reminds us to be grateful for the natural world and see the ways that the water in the skies is linked to all water on earth—including the water within our bodies! The next time it rains, instead of jumping to frustration, you might look to the sky and smile. Perhaps you’ll even see a makara.