Societal ideas about identity, gender, and sexuality have changed dramatically in recent years, allowing new possibilities for expression. Yet power structures embedded in religions with long-standing spiritual traditions present complex challenges to these new ideas for practitioners and teachers alike.

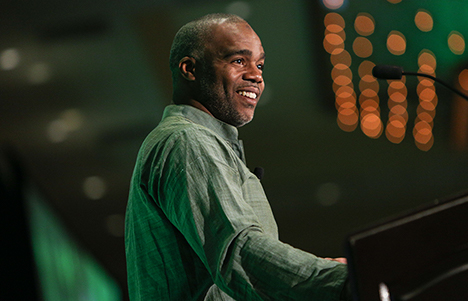

This spring at the Rubin, Buddhist lama and Harvard-trained theologian Lama Rod Owens met with meditation teacher Kate Johnson as a part of our Compassionate Action series. Together they explored how we can use this cultural moment as an opportunity to liberate our collective conditioning around power, pleasure, gender, sexuality, and consent.

Read adapted excerpts of their conversation below.

On forging your own spiritual path

Kate Johnson: You don’t call yourself a Tibetan lama but a lama who trained with Tibetans. What’s the distinction there?

Lama Rod Owens: I have gone through this period of leaving some of the structures of Tibetan Buddhism, because it actually creates harm for me. It’s an effort to claim the space of being an American tantric teacher. I want to practice Tantra within my cultural context—and from my cultural perspective as a person who is descended from slaves. I have to be me. I think that’s the beginning of creating an authentic practice.

You actually have to become yourself, you know? The risk is, “Will people be interested in me? Will people come to my talks, give me money, give me titles, will I get to come to the Rubin Museum?” These are the things we have to think about. This all lies at the root of how we create harm for ourselves in our communities. If we can’t be ourselves, then it’s more than likely you’re going to be a violent person.

Johnson: What forms do your practice take now that it’s no longer Tibetan?

Owens: It’s still rooted in tradition, but it’s more about exploring what it means to be in this body, in this country, all the things we’re calling upon in our practice. The protectors, the deities, the bodhisattvas, the ancestors . . . I want to bring ancestor practice into it, because I can pray to all these lineage lamas, but I want to pray for the beings who made sure that I was able to reincarnate into this body, to have the privileges I have now. I have been reincarnated into this body that has been dependent upon people like me, who have survived systematic oppression within samsara. I have to honor that.

On the relationship between gender, identity, and spirituality

Johnson: I was reading the book Open to Desire by Mark Epstein, and in the book he talks about psychoanalyst Jessica Benjamin. She discusses, not necessarily female desire, but feminine desire or the Yin form of desire, as a desire for space. And I was reflecting on my own coming into maturity and process of maturing around sexuality. Especially in my teens and twenties, I felt like an object because I was being looked at too closely, and just in terms of my parts, you know? And there’s something about this desire for space and spaciousness that I identify with, in terms of what enables me to feel desire. It’s like there’s a right amount of space, and it’s not so close that it’s picking me apart and reducing me to body parts, but it’s also not so far away that it’s clinical. It’s like desire requires this right spatial relationship. Does that align with the tantric view?

Owens: Yeah, absolutely. I mean, the female principle in Tantra is space. One of the things that’s really powerful about the traditional practices is that you’re going through practices where you’re imagining yourself to be different than what you are in reality. So you’re imagining yourself to be female and male, you know, or through some practices where you’re not gendered at all.

Johnson: And you visualize yourself as this?

Owens: Yeah, there’s a practice with Vajrayogini—she’s a fierce red deity—and you become her, regardless of who you are. You’re just divine, you become the embodiment of a divinity, and that means that there’s a spaciousness you’re entering into. But that spaciousness is actually the experience of suffering, initially. Because you’re trying to disrupt clinging to ego, which is creating the boundaries that we’re living in. For me, when I was moving into that space, I was like, “This is rough.” Because I didn’t know how to relate to boundlessness; I could only relate to boundaries. “This is who I am.”

And then in Tantric deity practices, you say, “You’re not this. Matter of fact, become that, and see what happens.” And that really plays with gender and gender identification. You can come through that like, “Wait, what are my pronouns now?” It had a profound impact on my attraction and how I related to my body. It gave me permission to touch into the feminine experience within my own body and mind. And it intensified pleasure, it intensified eroticism, it intensified how I began to be attracted to many other kinds of people. And it was actually decolonizing my sexuality.

On celibacy and sexual exploration

Johnson: When you make a choice not to engage in sexuality or sex, it doesn’t necessarily feel repressive. It can be a very freeing moment. But for me, it started to feel like this part of me is not welcome. And it was an interesting path to try to integrate that—like, most of our teachers are monastic teachers, how am I going to ask them? You know, that’s rude!

Owens: But I heard such a transformative teaching on sexuality from a Theravada nun that completely blew my mind open, because the renunciation gave her a positionality that helps her to be super objective and not attached to how she explored human sexuality.

Johnson: So she was still exploring sexuality, but as a celibate person?

Owens: Yeah. And several years ago, I used to do this program called Bringing Queerness to the Path, and my teaching partner was a Western monk in the Tibetan tradition. It was just profound, as a layperson, talking about sex, and as a monastic person talking about the expression of sexuality. Sangye was also gay, and he was like, “I’m still sexual though; I’m not having sex but I’m still sexual.”

About the Speakers

Kate Johnson works at the intersections of spiritual practice, social action, and creativity. She has been practicing Buddhist meditation in the Western Insight/Theravada tradition since her early twenties and is empowered to teach through Spirit Rock Meditation Center. She holds a BFA in dance from the Alvin Ailey School at Fordham University and an MA in performance studies from NYU.

Kate is a core faculty member of MIT’s Presencing Institute and has trained hundreds of leaders and changemakers in Social Presencing Theater, a mindfulness and dance improvisation methodology used to inform strategic planning and systems change in our complex world.

Lama Rod Owens is an author, activist, formally authorized Buddhist teacher, and graduate of Harvard Divinity School. He is the co-founder of Bhumisparsha, a Tantric Buddhist practice community, as well as a co-author of Radical Dharma: Talking Race, Love, and Liberation. His next book on anger and love is due out later this fall.

Image Credit

The Red Yogini; Vajrayogini; Tibet; 17th century; metalwork with pigments; Rubin Museum of Art; C2003.18.1 (HAR 65230)

The Red Yogini; Vajrayogini; Tibet; 19th century; pigments on cloth; Rubin Museum of Art; C2002.24.11 (HAR 65127)

Power surrounds us and is an inescapable part of life. But its nature can be a little hard to pin down. Where does it come from, and how can it work for us?

To better understand power, we asked our Compassionate Action speakers Jungwon Kim of the Rainforest Alliance, author Ibrahim Abdul-Matin, and series host Kate Johnson what power means to them and how we can move through life more powerfully.

Meditation teacher Kate Johnson on Power:

“Greed has power, hatred has power, and fear has power. But so does love, so does generosity—and these are the kinds of powers that can fuel profound social change. I think part of our [mindfulness] practice is to look within and notice what is powering our actions in the world. If we know strategies and tools to shift our power source from fear to trust, from hatred to curiosity, then we can actually make a different kind of impact, one that is more aligned with our values.

We each have great individual and personal power that we can use to transform ourselves, to transform our relationships, and to transform the world. Paradoxically, we might not always be aware of our power, especially if we happen to be empowered by society. What’s amazing is that we can also use our individual and our relational power to start to shift these powerful social systems.

Want to learn how to access the clarity, connection, and courage needed to effect change in challenging times? Join us for our Compassionate Action series events throughout May and June. You’ll leave fortified, inspired, and more prepared to turn your wise intentions into compassionate action.”

Activist, Author, and Changemaker Ibrahim Abdul-Matin on Power:

“Knowing who you are is an important part of knowing what you want—knowing how you want the world to be. Power, in this instance, becomes about freedom, and freedom is not just the freedom to do whatever you want. It’s freedom to control your lower self, to master yourself. Mastery of yourself and controlling the part of yourself that’s going to hurt other people—that is true freedom. True freedom is being able to say “no” to certain things that are harmful, to stop people when they’re getting hurt. That’s true freedom because you’re allowing yourself to be the best human you can possibly be. That’s where the work is when it comes to inner power. You have to cultivate practices that are going to bring out the best in you, as opposed to practices that are going to let you go to the bottom rung and just do whatever you might feel is necessary, or what your body might feel is necessary. To me, mastery is critical to personal power.”

Jungwon Kim, the Head of Creative & Editorial at the Rainforest Alliance, on Power:

“To me, power is not only about brute strength or military force. Power is not always relational. Power is the drive that we have within us to express or create a vision that we have. When we think about power in those terms, we no longer measure it in degrees; we measure it in terms of the skill with which we are able to bring that vision to life. That allows us to expand the vocabulary we use to describe power to include terms like imagination, creativity, language, or even the ability to connect deeply with other people. And when we talk about connection, we begin to touch collective power, or power between us. Power between us is the ability to understand your vision, to look around and find others who share it, and to work toward it together”“”“with each person contributing their best effort and unique skills to that shared vision.”

Learn more about Power and our Compassionate Action series.

About the Contributors

Kate Johnson works at the intersections of spiritual practice, social action, and creativity. She has been practicing Buddhist meditation in the Western Insight/Theravada tradition since her early twenties and is empowered to teach through Spirit Rock Meditation Center. She holds a BFA in dance from the Alvin Ailey School at Fordham University and an MA in performance studies from NYU. Kate is a core faculty member of MIT’s Presencing Institute and has trained hundreds of leaders and changemakers in Social Presencing Theater, a mindfulness and dance improvisation methodology used to inform strategic planning and systems change in our complex world.

Ibrahim Abdul-Matin is a bright, playful spirit who authentically reflects and acts on bold questions. His artful blending of idealism and spiritual commitment with pragmatic application has led him into government, public administration, parenthood, and media. His unique voice has helped elevate the environmental vision of Islam, the spiritual opportunity of parenting, and the cultural and political side of sports.

Jungwon Kim is the Head of Creative & Editorial at the Rainforest Alliance, an international nonprofit organization working with farmers, forest communities, governments, businesses, and consumers to build a world where people and nature thrive in harmony.

To some viewers, Netflix’s hit series Russian Doll is a sexier, edgier, video-gamer update of the 1993 movie Groundhog Day. But for a practicing Buddhist, this new show offers a particularly rich trove of allusions to Buddhist ideas. In truth, for Buddhists, such ideas are everywhere and in everything, but I found Russian Doll particularly good spiritual fun.

The show begins (in this case, repeatedly) on our main character’s 36th birthday, a time when the first existentially angsty hints of a mid-life crisis may start to ripen into full bloom. As played by Natasha Lyonne, Nadia faces the issue of death head-on (often actually landing on her head) by repeatedly dying and coming back to life, only to relive her birthday over and over”¦maybe until she finally gets it right?

Spoiler alert: if you haven’t already done so, watch all 8 episodes now. As Buddha taught, there’s no time like the present.

The cycle of death and rebirth is just the show’s most obvious Buddhist theme. Russian Doll also plays with the Buddha’s teachings on interdependence and the wisdom teachings on emptiness: the ultimate nature of reality. Play is the key word here. This is a comedy, albeit often violent, sometimes bloody, and certainly dark.

In the playground of the East Village, Nadia and her male counterpart, Alan, eventually emerge having learned some powerful lessons tied to those Buddhist teachings.

The Cycle of Death, Rebirth, and Suffering

When Nadia looks in the bathroom mirror (or, in a few instances late in the series, at the absence of one) we can’t be sure if it’s the realization that she’s just died again or that she’s been given another chance at life that makes her say “Fuck.”

She’s grappling with two concepts central to Buddhism: reincarnation and the endless cycle of suffering known as samsara. The concept of reincarnation predates the birth of Buddha Shakyamuni in the 6th century BC, so the Buddha’s teachings assume an understanding that this life is just one of many along a timeless mental continuum. The first of his noble truths describes how our lives are characterized by suffering, or at the very least, by discomfort, a lack of abiding mental peace.

While the word “suffering” may seem a bit extreme, particularly to the young and fortunate, anyone who has lived long enough (maybe to 36?) understands this, at least to some degree. According to the second noble truth, because we suffer from distorted perceptions of reality, we are trapped in an endless cycle of death and rebirth known as samsara. The third and fourth noble truths outline a way out of samsara through meditation and developing wisdom and compassion, but understanding the nature of samsara, our current mode of existence, is essential. We generally have to learn the hard way, through suffering.

Having died and returned to life 22 times, with increasing fear and anguish each time, Nadia has experienced this cycle with her eyes wide open. As she says in the last episode, “Being a person is a fucking nightmare.” It seems she’s articulated the Buddhists concept of samsara pretty succinctly.

Interdependence

An only and ultimately abandoned child, Nadia has grown to be a loner who views commitment as “a base instinct for suckers and mediocres.” Though he yearns for connection and realizes its virtues, Alan’s compulsions clearly alienate those around him and he refuses to get help.

Their first point of connection is a video game that Nadia herself coded. “You created an impossible game with a single character who has to solve everything entirely on her own.” Alan tells her, “It’s stupid.” It’s also impossible.

As Ruth tells a misanthropic Nadia, “We need other people.” Moments later, after Ruth has gone, Nadia chokes on a chicken bone, alone, with no one to save her.

As the show repeatedly reveals, everyone is profoundly connected, a revelation tied to another Buddhist concept: interdependence.

Nadia and Alan moved toward this realization over the course of the show, with Alan ultimately trying to save Nadia in the finale by telling her, “You and I are intrinsically and inexplicably linked.”

According to Buddhist thought, this interdependence even goes beyond our relationships to one another. Everything, including our conception of self, is a dependent-related phenomenon, all related to our minds. This brings us to perhaps the most profound of Buddhist teachings touched on in Russian Doll: the concept of emptiness.

Emptiness

In the penultimate episode, “The Way Out,” Nadia has a breakthrough answer to her own question, “What do time and morality have in common? Relativity. They’re both relative to your experience. Time is relative to your experience. We’ve been experiencing time differently in these loops”¦but this tells us that somewhere time, linear time as we used to understand it, still exists.” As viewers, we’ve noticed the increasingly wilting flowers and rotting fruit across the episodes, so Nadia’s realization makes sense.

“Our universe has three spatial dimensions,” Nadia explains, cutting into a piece of that aforementioned fruit. “So it’s hard for us to picture a four-dimensional world, but computers do it all the time.”

“This is not good or bad,” Nadia explains, touching a bit on non-duality of a sort. “It’s just a bug. It’s like if a program keeps crashing, the crashing is just a symptom of a bug in the code.”

“I’m stuck with a mind that wants to kill me,” Alan says, realizing both the source of his dilemma and his salvation. With our minds, we invent ourselves (in truth, countless versions of ourselves) and likewise do we do ourselves in. From a Buddhist perspective, it is with our minds that we invent our whole world; we create our reality.

Alan and Nadia’s realizations touch on the Buddhist concept of “emptiness”—the total absence of the inherent, independent existence of all phenomenon, including the self. Through a profound realization of emptiness—motivated by compassion—it’s possible to wake up in enlightenment. Alan and Nadia’s words also hint at the source of what keeps us from reaching enlightenment—the so-called root delusion of self-grasping ignorance: a profound misunderstanding whereby we grasp at a self (and all other phenomenon) as existing inherently, independent of the mind perceiving—or more accurately, conceiving—it.

In Russian Doll, these concepts of emptiness and self-grasping are most obviously reflected, quite literally, in the recurrent theme of mirrors. As the mirrors disappear, Nadia and Alan move closer toward freedom. They can no longer see themselves, which is frightening. But they are even more terrified when others start disappearing. From a Buddhist perspective, that these two migrators begin to fear losing loved ones and to feel increasing compassion for everyone—engaging in the essential practice of developing empathy by mentally exchanging self with other—is very good news.

In the final episode as the two parallel universes take shape, we move most obviously into the place where Buddhist ideas meet quantum theory, where the observed is shaped by the observer, giving rise to the possibility of countless perspectives and therefore realities.

Nadia has overcome her self-destructive habits and even something of a death wish. She has experienced the pain of cyclic existence and seen the true nature of interdependence and emptiness. Her life force has grown. As she tells Ruth—with an apparent mix of resignation, comfort, and warmth—in a late episode, “I’ll see you in the next one.”

Katy Brennan teaches Buddhist meditation in the East Village.

The exhibition The Power of Intention: Reinventing the (Prayer) Wheel (on view through October 14, 2019) explores how intentions shape our connections with the world. To have an intention is to have a desire to act, but not all intentions truly become actions. Without an intention, on the other hand, our actions become aimless. The gap between intention and reality raises a basic question of right and wrong. Is it more important to have good intentions, or to perform actions that have good results?

Buddhism affirms the overarching importance of good intentions. Synonymous with good karma, positive intentions have the power to lead to better future circumstances and the possibility of liberation.

Intention in Buddhist Philosophy

The Sanskrit word cetana means intention or volition. Cetana organizes different parts of the mind to carry out a desired action. Karma means “action,” and according to the Buddhist sutras, the Buddha defined karma more specifically as the intention behind action. Although intention is distinct from the action itself, it must be coupled with a desire for the action to be carried out in reality, or it does not count as an intention. This intention determines whether the action is ethical, and whether it will produce good or bad results in the future. An evil course of action is driven by one of the three mental poisons (delusion, hatred and greed), plus an intention to have it carried out in reality. For instance, murder arises from hatred, linked to a desire to kill. According to the Buddhist philosopher Vasubandhu, intention encompasses not only our present desire or will, but also habitual tendencies which come from past deeds. Buddhism denies that there is a self, but instead the continuation of karma, propelled by intention, has the power to keep us trapped in samsara or to liberate us.

Vows and commitments

Good intentions in Buddhism may take shape in vows to perform good deeds and commit to spiritual practices. Many such commitments are laid out in the Vinaya, the portion of the Buddhist scripture that contains the rules of monastic life. A basic commitment that laypeople undertake is the five precepts: not to kill, steal, engage in sexual misconduct, lie, or take intoxicants. Those who desire to undertake more intensive spiritual commitments that entail celibacy will take the eight vows of a lay devotee or the ten vows of a novice monk or nun. Fully ordained monks and nuns submit to a much broader array of vows regulating how they eat, sleep, and behave in daily life. According to the tradition followed in Tibet, monks live by 253 vows and nuns live by 364 vows. These vows serve to concentrate the mind, to discourage material indulgence, and also to protect the reputation of the monastic community in the eyes of laypeople. In Mahayana Buddhism, practitioners are encouraged to arouse in their minds the aspiration to liberate all sentient beings, an intention known as bodhicitta. The bodhisattva vows support this intention. Tantric practices also entail certain commitments (samaya), which include maintaining the secrecy of the practice and seeing one’s guru as a buddha. The more serious the commitment, the greater the karmic consequences for violating it, so they should not be taken lightly.

Spreading good intentions

In Tibetan Buddhism, even if you do not have the committed practice of a monk, nun, or great saint, you can still perform many simple rituals or practices that spread good intentions. Buddhas and bodhisattvas are believed to have created short formulas or spells known as mantras, and longer versions known as dharanis, to put their compassionate intentions into concrete form. Their followers can easily spread these blessings, whether by reciting the mantras verbally or writing them down. For instance, Avalokiteshvara’s mantra om mani padme hum is written on numerous mani stones that dot the Tibetan landscape, imbuing it with the blessings of the bodhisattva of compassion. Prayer wheels contain mantras and dharanis written on rolls of paper so that someone who turns the wheel can release blessings with the touch of a hand (as featured in the exhibition Power of Intention). Though some Western observers thought the prayers wheels were nothing more than machines for prayer, it is the intention of the practitioner that activates the blessings so that they can be released into the world. Ideally, one who spins a prayer wheel should have pure intentions of body, speech, and mind and perform appropriate visualizations to receive their full benefits.

According to Buddhist philosophy, whether an action is good or bad depends primarily on the intention behind it. Depending on the intention, it will bear karmic fruit in good or bad results, and create the habit of doing more good or bad actions in turn. Even if you do not take spiritual vows or spin prayer wheels, there are still many ways you can reinforce your good intentions. What practices or habits help you spread good intentions through the world?

The Power of Intention: Reinventing the (Prayer) Wheel is supported by Lois and Bob Baylis, Barbara Bowman, the Ellen Bayard Weedon Foundation, the Ministry of Culture (Taiwan) and Taipei Cultural Center in New York, and the NYC Department of Cultural Affairs.

Female deities are revered in many different traditions throughout the Himalayas. While these traditions are not necessarily feminist by contemporary standards, they feature a range of beloved goddesses, bodhisattvas, and dakinis that reflect fascinating ideas about feminine power and have inspired people across time and cultures.

The Energy of the Many-Formed Goddess

Hinduism, the most prevalent religion in India and Nepal, is known for its millions of gods of diverse origins, forms, and abilities, with an equal multiplicity of goddesses. They embody compassionate as well as fearsome forces: Lakshmi delivers good fortune, Parvati embodies the Himalayas and ascetic practice, Sitala cures smallpox and other childhood diseases, Durga fiercely slays the buffalo demon and negative forces, and Kali is even more terrifying. One could not name every goddess in a lifetime.

Hindus often choose a single deity to worship as supreme and encompassing other divine forms. The Shaktas, for example, worship the goddess Devi. The Shaktas are so named because of the goddess’s shakti, the feminine power, capacity, or energy that is behind the universe, without which the male gods would be inert. Shaktas are not necessarily feminists, and rulers sought to obtain shakti for the sake of political dominion.

In Nepal, little girls are recognized as Kumari and worshipped in temples as living goddesses. This was especially important to the country’s former monarchy. Historically, rulers throughout India patronized Durga as a goddess of war and popularized the Navaratra festival of nine nights of worship.

Women and Buddhist Awakening (Bodhisattvas)

Buddhists have sometimes debated whether a woman can achieve awakening, but the Buddha clearly answered in the affirmative, according to a story found in the Vianaya. When the Buddha’s aunt Mahaprajapti, tried to convince the reluctant Buddha to ordain nuns, she asked the Buddha whether women who renounce domestic life and devote themselves to the Buddhist path can attain nirvana. The Buddha said that they can, so he set up the bhikshuni (nun’s) order of the sangha. However, he prophesied the demise of the dharma and placed heavy restrictions on the nuns.

In Mahayana Buddhism there was a tradition that only men could become awakened to full buddhahood. The Vimalakirti Sutra challenges this notion in its portrayal of an enlightened goddess, who befuddles the skeptical disciple Shariptura by changing him into a woman and herself into a man. Whether or not this story is meant to convey a feminist message, it demonstrates the power of the Mahayana teaching to overcome such empty dualities as gender.

Mahayana Buddhism has a number of female buddhas and bodhisattvas. Tara is among the most popular of these in Tibet, revered for her powers of salvation, protection, healing, and ability to accomplish all Buddha activities. In one story of her origins, she vowed to become a buddha in a female form, proclaiming the emptiness of gender.

The Tantric Power of the Dakini

Tibetan Buddhism, following the tantric practices of the Vajrayana, considers sexuality to be part of Buddhist path, not as a cause of harmful attachment but as a way to create body and mind. Some Tibetan traditions therefore offer more opportunities for non-celibate practitioners beyond the confines of monasteries, which offered few opportunities for women in Tibet. There is a debate among scholars whether tantra actually improved the status of women, since male practitioners remained dominant, but there are many examples of female power in Tantric Tibetan Buddhism.

Tibetan Buddhists revere female spiritual beings known as dakinis, who teach and guide practitioners to awakening, and tantric practitioners are required to respect and not disparage women. Female deities in tantra are not only consorts of male deities. The dakini Vajrayogini embodies the wisdom of all buddhas, and her visualization and practice is reserved for the most advanced tantric initiates. On a more human level, a number of Tibetan women rose to prominence for their tantric teachings, particularly Machik Lapdron who originated the practice of cho (“cutting off”). Her practice, revered across traditions, emphasizes generosity and freedom from ego-clinging through visualizations of offering the body to demons.

Hero Image Credit

Kaumari; Nepal; 17th or 18th century; gilt copper alloy with semiprecious stone inlays; Rubin Museum of Art;C2006.44.1 (HAR 65693)

This blog post is written by William Dewey, curatorial fellow at the Rubin. He holds a PhD in Religious Studies from the University of California, Santa Barbara and has taught at the Rangjung Yeshe Institute in Nepal.

What is the relationship between religion and power? Since, the Himalayan artworks in the Rubin Museum collection are deeply rooted in the religious traditions of Hinduism and Buddhism, they are the perfect starting point to investigating this complex relationship.

Religious power systems are deeply intertwined with the power systems of gender, political rule, scholarship, and nature. In Himalayan cultures, sacred objects, people, and places are believed to be imbued with capacities and abilities far beyond the world we ordinarily see, and the art at the Rubin reflects this.

Buddhism and Political Power

The 2019 exhibition Faith and Empire: Art and Politics in Tibetan Buddhism explores the intertwining of political and religious power. Today we often question whether church and state should mix. Do the two complement each other or corrupt each other?

While religion and politics were not always seen as distinct in Asia, Buddhists debated whether true spiritual liberation was compatible with ruling a kingdom. The Buddha himself was raised to be a great king, but he renounced luxury and power to seek a solution to earthly suffering. By contrast a great emperor a could use political power to spread the Buddhist message and convert the world. Emperor Ashoka (268″“232 BCE) fought bloody wars to conquer India, then issued edicts expressing remorse for violence and encouraging religious tolerance and compassion among his subjects. Buddhists credit him with sending out missionaries and distributing the Buddha’s relics all over Asia.

Tibetan Spiritual Rule

From the beginnings of the Tibetan Empire, Tibetan rule depended on spiritual power. In contrast to European monarchies, which invoked the divine right of kings, Tibetan rulers were believed themselves to be enlightened or divine beings. According to legend, the first Tibetan rulers descended from gods who climbed from heaven on a sky-rope. The emperors Songsten Gampo, Trisong Detsen, and Relpachen are depicted as bodhisattvas who introduced Buddhism through images, monasteries, and holy texts.

Early rulers sought political control and enhanced personal power by controlling the secret rites of tantra. Foreign rulers also viewed Tibetan tantric masters as the keys to empire, especially after Chinggis (Genghis) Khan conquered Tibet. In exchange for their initiation into rituals that empowered them for global conquest, the Mongols allowed the hereditary Sakya masters to rule Tibet as their vassals after 1260. Later rulers of China and Mongolia sought out similar patron-priest relationships (choyon) with Tibetan rulers to solidify their rule, which encouraged Tibetan Buddhism to spread further.

The Dalai Lamas

When the Fifth Dalai Lama came to power in 1642, he proclaimed a union of religion and politics (chosi sungdrel) in Tibet. The Dalai Lamas are the best-known example of a Tibetan reincarnating lineage, in which each Dalai Lama is believed to be the reincarnation of a previous one. As an embodiment of the compassionate bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara, the Dalai Lama was believed to choose the circumstances under which he would be reborn. A lot of intrigue resulted from new incarnations being children who were too young to rule. Tibetan regents and Qing imperial governors often schemed to keep the Dalai Lamas off the throne. Four Dalai Lamas mysteriously died before the age of 20, and the Thirteenth Dalai Lama, the last one who had full power over Tibet in the early 20th century, took his throne after uncovering an attempt by the regent to kill him with black magic. The current Dalai Lama’s religious prestige made him a natural leader of Tibetans in exile after 1959, but he recently has recently relinquished political power.

A Close Union

While the Buddha preached a renunciation of the world, his own life narrative intertwined the spiritual power of the dharma and political power. Buddhism could not have spread throughout Asia without the support of great emperors like Ashoka, and Buddhists consequently respected these ruler as deities. Tibetan Buddhism in particular depended on political power for its propagation, from the great dharma kings who founded Tibet to the Mongol and Chinese empires that bolstered their power through supernatural techniques and spiritual alliances. This close union of religion and politics in Tibet has not always been harmonious, as evidenced by sectarian conflicts and monastic intrigues, but it certainly has been a defining part of the region’s history.

See all of the works of art featured in this blog post and experience our year of Power: Within and Between Us on your next visit to the Rubin.

Image Credit

Crowned Buddha Northeastern India; Pala period (750″“1174); 10th century; Stone; Rubin Museum of Art; C2013.14

Are you searching to find the perfect holiday or New Year’s gift? This winter, give someone special a membership to an oasis of calm amid the chaos of New York City, a place where they can expand their mind, explore sacred spaces, and connect with others.

A membership to the Rubin Museum is valuable long past the holiday season, with yearlong access to special exhibitions, benefits, and more. Purchase a gift membership now or read on to explore 5 reasons why a gift membership is the perfect match for your inspiration-seeking loved one!

1. Members get free access to the Museum—for two

Members can visit the Rubin Museum for free, discovering art from regions across Asia, from centuries past to the present day. As they unpack the ideas and philosophies in Himalayan art, Rubin visitors become equipped to face their own lives with a fresh perspective and new inspiration. And because members get free admission for two, they can share this experience with a friend or loved one every time they visit the Rubin.

A favorite spot for members is our Tibetan Buddhist Shrine Room, a focal point of the Museum that transports the viewer into a traditional Tibetan household shrine.

2. Museum Membership provides refuge from the chaos of New York

Give the gift of a calm, renewed mind this winter. Free weekly meditation classes, included with any membership, provide visitors with a refuge from the world around them, as well as the tools to engage with it more consciously. Designed to fit into a lunch break, each session is led by an expert teacher and inspired by a different work of art from the Rubin Museum’s collection.

In addition, our ART+PRACTICE membership grants two free tickets to a select wellness program.

3. Members get discounts on unique programs and experiences to feed curious minds

The Museum’s guest speakers and performers are hand-picked to pique visitors’ curiosity and expand their minds. In 2019 our spring conversation series, Brainwave, delves into dynamic power relationships at work, at home, and society at large.

If music is more your loved one’s taste, they can enjoy the Naked Soul series in the New Year, featuring intimate, acoustic performances from remarkable singers on select Friday evenings. The music in these shows draws upon the universal themes of the Himalayan art in our galleries—like compassion and the fleeting beauty of life.

Members get a 20% discount on all programs, and with our ART+WISDOM membership, members also receive free tickets for two to a select onstage conversation.

4. Membership brings you into a community of mindful, lifelong learners

Throughout the year the Rubin is a place to gather, relax, eat and drink, learn, and connect with others in our community. For many members, the Museum is a home away from home.

We celebrate this community at our Annual Members Reception, an elegant evening where guests have the opportunity to mingle with others who help make the Rubin possible while enjoying live music, hors d’oeuvres, and drinks.

Looking for more connection? Our ART+WISDOM membership includes regular meetups with other members of the Rubin community in Café Serai. With our ART+ABUNDANCE membership, you can also join private Shrine Room hours when the Museum is closed to the general public.

5. Membership helps keep our mission alive

At the Rubin Museum, we strive to create an environment that stimulates learning, promotes empathy and understanding of others, and inspires personal connections. A gift membership helps us achieve this mission, and invites your loved one to be an essential part of our community.

With a variety of membership levels, there’s a perfect experience for every person in your life. Join us this year at the Rubin.

Even if you’ve never meditated before, you probably know someone who has. Psychologists, scientists, teachers of religion and contemplative practices, and everyday people around the world are recognizing the benefits of focusing the mind.

Meditation has existed in different forms for thousands of years and is well-represented in the Rubin Museum’s collection of Himalayan art. Inspired by our art and the wisdom and practices it represents, this guide will provide guidance for those who are interested in trying meditation for the first time, or those who want to approach their meditation practice from a new perspective.

You can also listen to our weekly Mindfulness Meditation podcast for more.

The foundation of Buddhist meditation: samatha

The first thing to know is that there are lots of different types of meditation. Generally, in Buddhist traditions the first form of meditation taught is called samatha, a word in the Pali language that is often translated to mean “calm abiding.” Once you’ve been introduced to samatha, you’ll have an understanding of mindful techniques necessary for any mediation practice.

The Stupa above represents the mind of the Buddha, developed by the practice of meditation.

How samatha builds focus and reduces anxiety

Today there are devices and services constantly trying to grab our attention, whether it’s that new series on Netflix, updates on your newsfeed, or ads reminding you to buy what you just looked at on Amazon. With so many things pulling us in different directions, it’s no wonder many of us feel uncentered.

Samatha proposes that a lot of our anxiety simply comes from our inability to stay focused, with our mind clinging to each passing thought, like a monkey moving from branch to branch in the trees. But with training, the mind becomes less flighty and concentration grows. The less the mind moves, the more stable it becomes, building mindfulness—greater clarity in both thought and action.

Choosing an object for your meditation

The first step in practicing samatha is finding something to focus on, also known as your single focus object (SFO for short). The SFO could be any one object that occupies the senses, though Buddhists traditionally use the breath as an SFO, since it’s something that always stays with you. Other common objects of focus are sound, feelings in the body, or an object to look at. The idea here isn’t to change anything that you are experiencing, but rather to simply notice how it truly is.

Beginning the meditation

When you’re ready to start meditating, find a comfortable position. Traditionally, Buddhists sit on the floor to meditate, but feel free to sit in a chair, stand up, or even lie down if that works best for you. If you do choose to sit, make sure your back is straight, but not strained—it should be relaxed and alert, a good metaphor for your meditation practice.

Once you are comfortable in your body, move your attention to your SFO. That’s all it takes to meditate! The most important part is to gently bring your mind back to your SFO when it wanders.

How to deal with distractions

Before you even ask, just know that you will not be able to “stop thinking” and you will certainly get distracted. That’s OK! Expect thoughts and feelings, both positive and negative, to arise. The key here is to simply notice that you have been distracted and then move your attention back to your SFO without judging yourself. This will probably happen dozens or even hundreds of times during a meditation session and is not an indicator of “failure.” Instead, being kind to yourself in that moment is part of the practice.

While people often think that the goal of meditation is to stop all thought, that is simply not true. Once you are more familiar with your mind’s activity, you will become more aware of your thought patterns and strengthen your ability to respond consciously rather than react unconsciously, offering you more stability and balance.

How frequently to meditate

Many meditation teachers will tell you that what matters is not how long you meditate but rather the consistency of your practice. If you can practice 20 minutes a day before work, great! If you can’t manage to do that, try 10 minutes, 5 minutes, or even 3 minutes. Try doing 3 four-minute sessions with small breaks in between. Have a sense of playfulness with your practice and find what works best for you.

How to maintain your meditation practice

If you’re in the NYC area, you can attend our weekly mindfulness programs, see the meditative art in our galleries, and learn about the different themes it contains. Every Wednesday we invite local meditation teachers to share their expertise and unpack the themes reflected in the art. If you can’t visit in person, you can listen to our Mindfulness Meditation podcast for weekly inspiration.

We all knows that actions have consequences. We see it in the little things, like heating water to a boil, as well as large-scale events, such as global warming and climate change. The word karma defines this cause and effect that we experience in our lives. While karma is often thought of on a personal level, the world is beginning to feel the collective karma of our actions as the threat of a climate crisis becomes very real.

Karma plays a huge role in the art featured in the Rubin Museum’s collection of art from the Himalayan region. Traditionally, Himalayan cultures have had strong connections to their environment, personifying mountains and lakes as gods and goddesses. If these forces weren’t properly respected, the deities would strike back with the power of nature.

Below you’ll find examples from our art collection exploring the connections between cause, effect, and nature, providing an inspirational model for thinking about our relationship with our struggling planet.

Gods Who Control the Earth and Skies

Clouds hold a special significance in Nepal because of their association with the life-bringing monsoon rains. In this sculpture of Indra, the Hindu king of the gods, you’ll notice an intricate cloud motif on his crown. Indra is from the ancient Indian Vedic tradition, which was influenced by a largely agricultural society and is still practiced in Nepal to this day. The Nepalese remain dependent on the annual monsoon rainfalls, which are growing increasingly erratic due to climate change.

This sculpture features Kula Khari, protector of a mountain known as Lodrak, which is located south of Lhasa near the Bhutanese border. Locals would pray to this protector god to prevent natural disasters. Here the god rides a yak, highlighting the unique landscape of the mountainous Himalayan terrain. The artist who created this sculpture emphasized this environment by cleverly using simple, pointed, staggered forms around Kula Khari to indicate the surrounding mountains. The disproportionate scale of these topographical contours to Kula Khari, his yak, and the architecture behind him conveys the sense of a remote temple in the mountains. When a natural disaster occurs in Tibet, the local populace attributes it angered deities.

Nature Motifs in Himalayan Art

Motifs like those in the image above emphasize Buddhism’s everlasting connection to nature. Marichi, the Goddess of the Dawn, depicted in this sculpture, is most commonly portrayed in a chariot of the sun pulled by seven pigs, removing obstacles with her radiant light. This sculpture presents her as an Indian princess, holding a vajra—the Buddhist symbol resembling a lightning bolt—and a branch of the sacred ashoka tree, which is said to represent beauty and seduction.

Make an offering to this sculpture and you’ll form a karmic connection with Green Tara. The goddess represents the potential for life, and with life, the capacity for people to change and transcend. In this sculpture of Tara, lush imagery of birds, flowers, and trees bloom behind her.

Despite the unusual style of this brass sculpture, the iconography follows age-old conventions. Seated in a posture of royal ease with a light sway and one leg hanging downward, Green Tara is supported by a branch of her lotus seat. The lotus is one of the most common symbols in Himalayan cultures, representing enlightenment. The goddess also performs the hand gesture of giving and holds the stalk of a blue lily in her left hand, which was once painted red.

Using Materials from the Earth

Most materials used for creating paintings and sculptures come directly from the earth, deepening the connection between Himalayan art and the environment. Visit our Materials and Techniques section on the second floor to see the process by which thangkas, or Tibetan Buddhist scroll paintings, are created. You’ll notice the brightly colored paints made from crushed minerals and glue that artists use to bring paintings alive.

Vocalist, composer, and ethnographer Kavita Shah returns to The Rubin this Friday to present her interdisciplinary work “Folk Songs of Naboréa.” What does the music of a futuristic, post-nuclear society sound like—one in which humans have abandoned technology and national and racial identities have eroded? Kavita answers this question and more as she engages us in understanding the rituals of Naboréa.

1. What about folk music inspires you?

Folk music inspires me because it is a reflection of the rituals that we hold sacred as humans. Wherever you go on Earth, you will find songs that mark important events in society and in daily life: birth, coming of age, death, sleeping, harvesting crops, etc. It’s amazing to me that there is a common thread in these songs even if they developed independently and worlds apart. As such, for me folk music—which oftentimes is also vocal music, transmitted orally from one generation to the next—contains implicit knowledge about who we are as humans and the values we share across time. I feel strongly that this ancient knowledge is something we can continue to learn from and apply to the most pressing issues facing society today.

2. What other art forms will we hear in this piece?

You will hear elements of extended vocal technique, jazz improvisation and harmony, 12-tone composition, “folk” harmonies (thirds, pentatonics), and polyrhythms. Aside from hearing, it is seeing that brings this piece to life, as we integrate movement into the music to tell the story of Naboréa.

3. How is “Folk Songs of Naboréa” different from your past works?

“Folk Songs of Naboréa” is my first large-scale, interdisciplinary work. It departs from the more conventional performance setting that I am used to, which is performing with an ensemble directly for the audience. Here there is no band and no amplification—just 7 voices (and a kora in one piece, which embodies a dream from the past). It is also different in that there is an overarching story line about life in Naboréa, and the piece incorporates movement and theatrical elements to convey that story.

4. You’ve performed here several times before. What do you like best about being at the Rubin?

The Rubin is like a second home to me in New York, and performing here has given me the chance to develop my craft by engaging, increasingly with each performance, with aesthetics and broader thematics to contextualize my music. It also connects me to my Indian heritage, sometimes to things about my own past that I have buried and forgotten, and to my spirituality, which plays a big role in my compositional process.

5. What can visitors expect from this performance?

Visitors can expect an immersive experience through which they are transported to another world. Naboréa also embodies a truly multiracial and multi-phonic society, one in which all my rich and diverse inspirations can live together in harmony and in dialogue, without fear of labels or cultural hierarchy. To share this possibility with the audience at a time of such political and social polarization in our society is to share an extremely powerful message of inclusion.

Tickets and more information about Kavita Shah’s “Folk Songs of Naboréa” on October 26, 2018.

More about the Performer

Kavita Shah is a vocalist, composer, and lifelong New Yorker who makes work in deep engagement with the jazz idiom while addressing and advancing its global sensibilities. Hailed by NPR for possessing an “amazing dexterity for musical languages,” Kavita incorporates ethnographic work on Latin American, West African, and South Asian traditions into her music. Her 2014 debut album “Visions,” co-produced by Lionel Loueke, was released to great critical acclaim, and her 2017 Park Avenue Armory premiere “Folk Songs of Naboréa” was named a Top 10 concert of the year by Nate Chinen of the jazz radio station WBGO. In 2018, Kavita released “Interplay,” an album of standards and originals in duet with bass virtuoso François Moutin, which was nominated for a Victoire de la Musique (French Grammy Award) for Jazz Album of the Year. Kavita regularly performs her music at major concert halls, festivals, and clubs on six continents. She holds an A.B. in Latin American Studies from Harvard and an M.M. in Jazz Voice from Manhattan School of Music.

Image Credit

Photograph by Da Ping Luo for Park Avenue Armory

While yoga’s popularity in the United States has grown exponentially over the past few decades, it’s hardly a new phenomenon. The roots of yoga extend far back into ancient Indian history as a varied spiritual tradition with some practices you won’t be able to learn at your local studio. Below, we’ll explore the development of yoga through some of our favorite pieces from the Rubin Museum’s collection.

Rig Veda

The use of the word yoga can be traced back to the Rig Veda, a collection of ritual hymns used to maintain order in the universe. This sculpture depicts Indra, king of the gods according to the Rig Veda. The Rig Veda is considered the earliest text of what became the Hindu tradition. In the hymns, yoga often refers to yoking, as in yoking two horses together. It also refers to yoking the physical self with the spiritual world, laying the groundwork for the development of a whole host of spiritual practices that are all part of the yogic tradition.

The Buddha

While yoga is most associated with Hinduism, all spiritual traditions in India have their own types of yoga, including Buddhism. According to the life story of the Buddha, while seeking enlightenment he met with every spiritual teacher he could find, sampling all of the yogic traditions within India at the time. After spending time practicing extreme ascetic yoga, he concluded that he was no closer to enlightenment. Rejecting the extreme asceticism, he embraced an approach that was a “middle way” between the extremes of indulgence and and complete renunciation. He ate some food, found a comfortable seat under a tree, and soon became enlightened. This story demonstrates how the religious dialogue between Hinduism and Buddhism fueled developments in yogic traditions.

Tantra

Another example of how Buddhism and Hinduism intertwined is often found with various yogic figures, with both traditions often claiming the same person as their own. Jalandhara is one of these yogis. You may be familiar with his name if you’ve ever performed the pose Jalandhara bandha (locking your chin to your chest) in yoga class. While the Hindu tradition considers him to be a form of Shiva, the Buddhist traditions reveres him as a Mahasiddha, one of the great Buddhist tantric masters from India’s medieval period (7th”“13th centuries CE).

One of the major yogic developments during the medieval period of Indian history is tantra. Not for the faint of heart, what’s unique about tantric yoga is that it promises a quick method to achieving enlightenment. Through extensive rituals and intense visualization practices, the yogin transforms their physical aspect into that of an enlightened being. One tantric method involves using a mandala like the one above to help visualize oneself as a deity. Though tantra’s appeal lies in its expediency, it must be practiced under the guidance of a master to ensure the student won’t fall into the trappings of this intense practice.

There are many other artworks related to yoga in the Rubin’s collection. If you want to learn more,plan a visit to the Museum or arrange a special yoga group experience at the Rubin.

This fall the Rubin is screening Walk With Me, the 2017 documentary about Zen Buddhist master Thich Nhat Hanh and his monastic community, called Plum Village, in rural France. The movie immerses you in the sights, sounds, and daily rituals of the community, and some people find that watching it can be a quasi-meditative experience. But it doesn’t delve into the fascinating life and work of Thich Nhat Hanh, whose philosophy of Engaged Buddhism, as well as his efforts as an environmental advocate, have special relevance to our fall Karma series, which applies ancient wisdom to the of-the-moment question of how we can build a sustainable future.

The Birth of Engaged Buddhism

Thich Nhat Hanh’s ideas about Engaged Buddhism started taking shape when he was a peace activist during the Vietnam War. “When bombs begin to fall on people, you cannot stay in the meditation hall all of the time,” he said in an interview with Lion’s Roar magazine. “When I was a novice in Vietnam, we young monks witnessed the suffering caused by the war. So we were very eager to practice Buddhism in such a way that we could bring it into society. That was not easy because the tradition does not directly offer Engaged Buddhism. So we had to do it by ourselves. That was the birth of Engaged Buddhism.”

From Awareness to Action

In a nutshell, Engaged Buddhism means connecting individual meditation practice to global ethics and social action. “Meditation means to be aware of what is happening in the present moment—to your body, to your feelings, to your environment,” he said in an interview with Tricycle magazine. “But if you see and if you don’t do anything, where is your awareness? Then where would your enlightenment be? Your compassion?” This general idea is fleshed out in the Five Mindfulness Trainings, which distill teachings of the Buddha into concrete, nonsectarian guidelines for mindful living in the modern world. You can read about them in detail on the Plum Village website.

The Fifth Mindfulness Training, which relates to mindful consumption, has the greatest relevance to environmental sustainability. “I will contemplate interbeing and consume in a way that preserves peace, joy, and well-being in my body and consciousness, and in the collective body and consciousness of my family, my society and the Earth.” On an individual level, this can mean eating less meat or none at all, in order to promote your own health and prevent cruelty to animals. Eating less meat also has a global environmental impact, since raising livestock consumes more natural resources than raising grains or vegetables. This same general principle applies to all sorts of consumption, from fuel to electronic gadgets, to extra food you might want but not need.

Thich Nhat Hanh’s Environmental Advocacy

This approach has fueled Thich Nhat Hanh’s impressive work as an advocate for the environment. In 2015 he and other Buddhist leaders, including the Dalai Lama, made a shared declaration to world governments in anticipation of the Paris Climate Agreement. He made a similar submission to the United Nations in 2014. He has also written two books about environmental sustainability: the bestseller The World We Have Now and Love Letter to the Earth. “The situation the Earth is in today has been created by unmindful production and unmindful consumption. We consume to forget our worries and our anxieties. Tranquilising ourselves with over-consumption is not the way,” he wrote in The World We Have Now.

“We have constructed a system we can’t control. It imposes itself on us, and we become its slaves and victims.”

Engaged Buddhism asks us to consume mindfully for our own benefit, so that we can have a healthier body and a deeper awareness of our interconnection with the natural world. It also asks us to take social action to help change the social and economic systems that drive global overconsumption, with Thich Nhat Hanh’s leadership as an example. What can you do promote mindful consumption, for yourself and for the world?