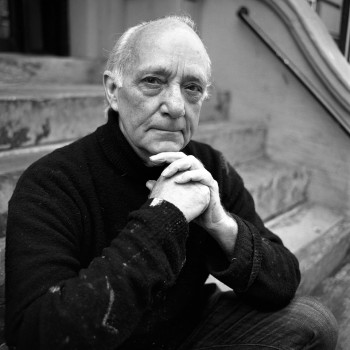

The Rubin is proud to frequently collaborate with fascinating and creative guest educators. One of them, Marshall Arisman—an artist, illustrator, and Chair of the MFA Illustration as Visual Essay program at the School of Visual Arts—hosted the art-making workshop Drawing with a Comb at the Museum earlier this month.

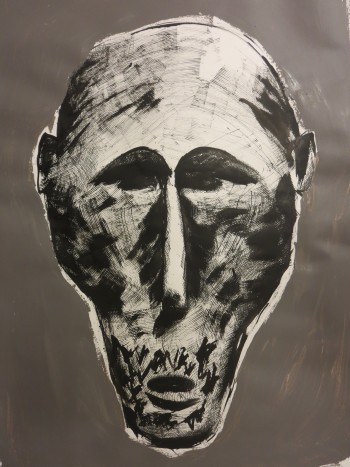

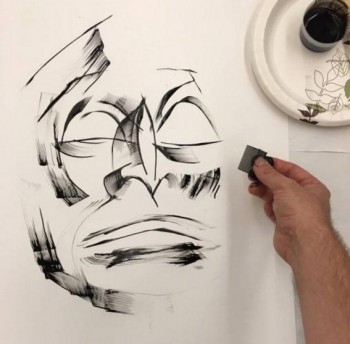

Attendees first made pencil sketches, working with over seventy masks on display in our exhibition, Becoming Another: The Power of Masks. Afterwards, they made drawings using pocket combs dipped in India ink. The results were amazing!

Throughout the afternoon, Marshall shared some wonderful anecdotes and insights about art and art-making. Intrigued, Laura Lombard, Head of Adult and Academic Programs at the Museum, followed-up with some questions for Marshall on his artistic techniques and upcoming projects:

What inspired you to first make drawings using a pocket comb?

“By the late 60’s I was a regular contributor to the op-ed page of the New York Times. Color had not yet saturated the newsprint. All drawings were black and white. My earlier work was done in the technique of cross-hatching, a series of parallel overlapping lines that follow the form that you are drawing. Cross-hatching can be tedious and time consuming. Like most of my Eureka moments the idea of drawing with a comb occurred while taking a bath. Instead of creating parallel lines one at a time a comb could make numerous parallel lines in one sweep.”

Most of the students in your workshop at the museum found it awkward to use a comb as a drawing tool. How might this sense of awkwardness be useful?

“If you give me a repetitious task in art I will fall asleep. Drawing with a comb keeps you attentive in the drawing process simply because you never have complete control of the tool. It was clear that the students in the workshop were much more comfortable doing a sketch in pencil than trying to draw with a comb. I believe that in that state of uncertainty you see more clearly.

Picasso said, “˜To draw you must close your eyes and sing.’ If you let go of your ego (your ego can’t draw) you may find the part of you that can. This means closing your eyes to not fall asleep. Put a comb in your hand instead of a pen.”

To see how this process works, take a look at the video made Marshall about the workshop:

People often think that a drawing should live up to a preconceived idea that they have in mind. Your approach, on the other hand, is different. How would you describe it?

“For many people a “˜good’ drawing is an accurate drawing of the object. This criteria starts at around twelve years of age. I was told I had “˜talent’ simply because I could draw a still life a little more realistically than my classmates. As I continued taking art classes and looking at How To Draw books I stopped learning how to draw. The direct connection between looking and drawing was replaced with a mechanical system of block buildings.

For example: to draw a head, first draw an oval shape. To draw the body, draw a cone, etc. These approaches produce odd, lifeless drawings, maybe more accurate but without a soul. Even the most untrained person can create a “˜good’ drawing if the judgement is not how close to a photograph the drawing is but rather is there honesty and sincerity in the drawing. If there is, it will have some power. It is a “˜good’ drawing, even though the person who did it thinks it’s bad. Picasso understood with great clarity that the creatures of habit are the enemy of art. His comment, “˜It took me four years to paint like Raphael but a lifetime to paint like a child,’ is a masterpiece.”

As both an illustrator and a fine artist, the types of images you create can be applied to either field seamlessly. When did you first realize this? Who or what inspired you to work this way, e.g., other artists, illustrators, musicians?

“David Smith, the sculptor, visited Pratt my senior year. As an art student, I had no clarity about commercial or fine art and who did what. He smiled when I asked the question, “˜Isn’t art made only for the needs of another person and not the artist commercial art?’ He said, “˜art made for the needs of the artist is fine art.’ Under that definition I know a lot of “˜fine’ artists who are commercial artists and commercials artists who are fine artists.

As a figurative artist the primary issue for me is not the printed page or gallery wall. The issue is content. Much of my personal work has been reproduced in magazines, newspapers etc. as illustrations for an article. I haven’t had a problem with that.”

Recently you made A Postcard From Lily Dale a film about your experiences growing up in a small town in upstate New York. What do you find surprising about this project, something that you wouldn’t have imagined when you set out to make a film?

“Many of us were lucky enough to have a gifted person see something in us before we were aware of it, maybe a grade school teacher, coach, aunt, uncle or friend. For me, that person was my grandmother, a Spiritualist minister, medium, and artist. The film started as a ten-minute homage to her. The surprise was how many living mediums knew and had great fondness for her. The film, A Postcard From Lily Dale, expanded to an hour in length and renewed my interest in Lily Dale, a Spiritualist Community in upstate New York.”

What art projects are you working on right now?

“My grandmother would look me in the eye and say, “˜You must learn to stand in the space between the angels and demons.’ For the past several years I have been painting Angels and Demons. One wall of my studio is covered in demons, the opposite wall covered in angels. I often stand in the space between the two walls and think about my grandmother.”

If you’re interested participating in creative projects at the Rubin, join us on November 14 for the Mala Workshop with Satya Jewelry. The mala is a traditional garland of 108 prayer beads. Every bead represents a truth, and meditating on them with an affirmation, or mantra, is used to bring peace of mind. In this fun, inspiring workshop participants will learn the sacred art of mala making and how mala are used in daily practice. Each participant will leave the workshop with a one-of-a-kind mala bead necklace. Learn more about the workshop