Learn about the processes and methods for creating Himalayan art that were developed over centuries, refined through collaborative efforts of patrons and artists, and encompass all known traditional art making media. To make three-dimensional objects, artists sculpt and carve in clay, stone, and wood, cast images in the round, and hammer repoussé reliefs in metal.

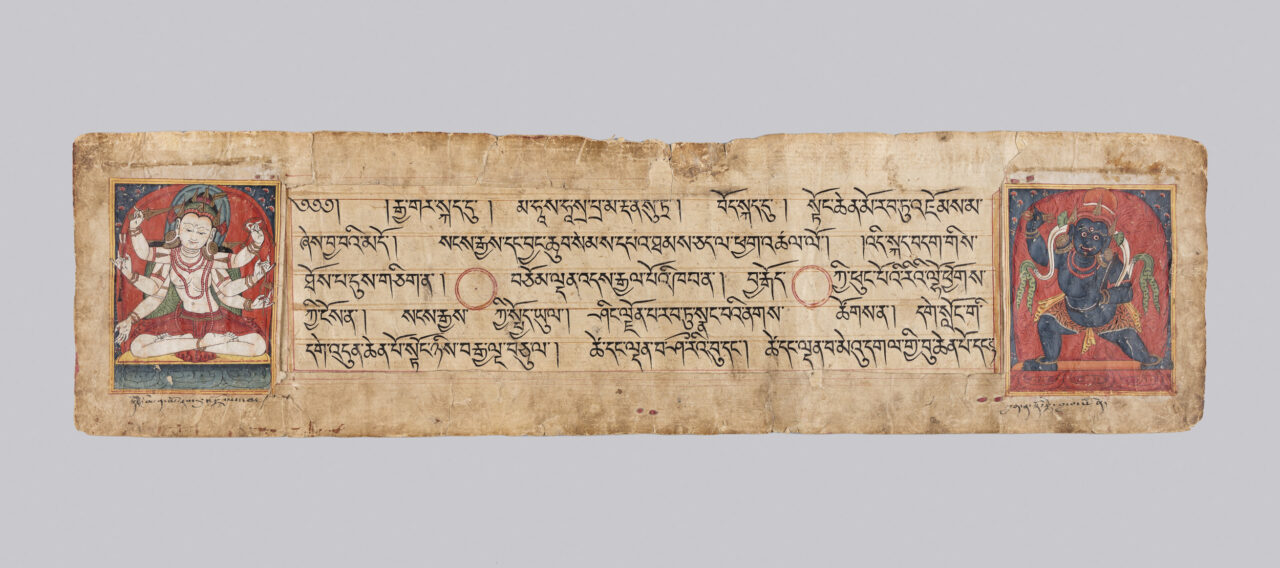

Textile artisans produce images using the appliqué technique, embroidery, and silk weaving and follow the same rules of proportion as the painters of two-dimensional works. Ordinary people also create objects, such as plaques made from molds using clay, and employ woodblocks to imprint images on cloth or paper to make prayer flags, amulets, and texts. Skilled painters create hanging scrolls called thangka using mineral pigments on prepared cloth or silk canvases.

In this section

in this sectionPainting on Cloth

Process of Thangka Painting

Thangka painting is a very process-oriented and rigorous art form that requires multiple precise steps.

Avalokiteshvara; 2022; Pigments on cotton, silk brocade; Rubin Museum of Art, SC2022.1-.4

Drawing

To sketch the figures in a thangka, the painter must know the proportions and measurements of each deity. These established guiding principles are called iconometry and maintained by artistic practice. The measurements are units that have no absolute values but are proportional in relation to each other—twelve small units to every large unit. In this example, the artist created a drawing of Avalokiteshvara and used units required for images of a seated deity.

First the artist drew guidelines, or gridlines, which allow him to draw the image at any size while retaining the relative proportions. The necessary gridlines include a central perpendicular line and two diagonals, among others. Artists use these guidelines to learn proportions, but after years of practice rarely employ them. Here the artist drew the basic figure, including color notations, using a charcoal pencil on paper.

Primed Canvas with Drawing and Application of Basic Colors

The artist stitched the canvas to four wooden rods along the four sides, then stretched it out and laced it firmly onto a larger wooden frame. Then he applied a thin layer of weak-consistency glue as a foundation to prevent the paint from cracking, losing its true color, or being absorbed into the cloth. Next he applied a smooth base of a substance called size mixed with lime and left it to dry. The artist then rubbed down the canvas several times to polish its surface with a smooth stone.

The artist sketched the figure directly on the primed canvas and then went over the drawing with a brush dipped in black ink. Following the color notations that indicate which colors to apply, he used basic paints for the background scenery of water, clouds, and so on, finishing one color at a time.

Application of Colors and Shading

After completing the background, the artist painted the central image, starting with the lotus throne, then the clothes, and finally the body. As with the background, he painted the lighter colors first followed by the darker ones. After the initial coats of color, the artist applied shading and gradual transitions of tone. This is a laborious work, requiring skillful color application and precision.

In general, the design of a painting and its degree of elaboration depend primarily on the painter’s familiarity with a particular school of art. Other important factors include the time available, the artist’s ability, and the desires and resources of the commissioning patron.

Avalokiteshvara, Full Thangka with Brocade Mount

Once the artist completed the shading, he painted patterns on the clothes, ornaments, and other areas that needed to be outlined in gold, red, and black. He also selectively polished some of the gold on the canvas to give the ornamentation a luminous quality. Last of all he painted the eyes of the deity. When the eyes are complete the painting becomes a true representation of the deity. This step is often followed by consecration; mantra syllables corresponding to the deity’s head, throat, and heart are painted on the back of the artwork. The deity is then believed to inhabit the image.

The artist trimmed the finished painting with white cord and mounted it on the brocade by stitching. The dimensions of the brocade mount are fixed: the bottom part is half the height of the painted area and widens slightly toward the bottom; the top part is half the bottom part’s height; and the side pieces are half as wide as the top’s height. The inner border is usually one quarter the side’s width.

The sides of the thangka were hemmed with red cord, and the bottom wooden rod was inserted and topped with caps. The rod facilitates the rolling up of the thangka, from the bottom upward, and serves as a weight to hold the painting flat when unrolled. The hanging cord also helps to tie the thangka when it is rolled up.

The Rubin Museum of Art, "The Making of a Thangka Painting," YouTube, January 23, 2023, 6:55, https://youtube.com/watch?v=ykteMInqG7w.

Objects in the Exhibition

Buchung Nubgya (b. 1979, Shigatse; lives and works in New York)

Pigments on cotton, silk brocade

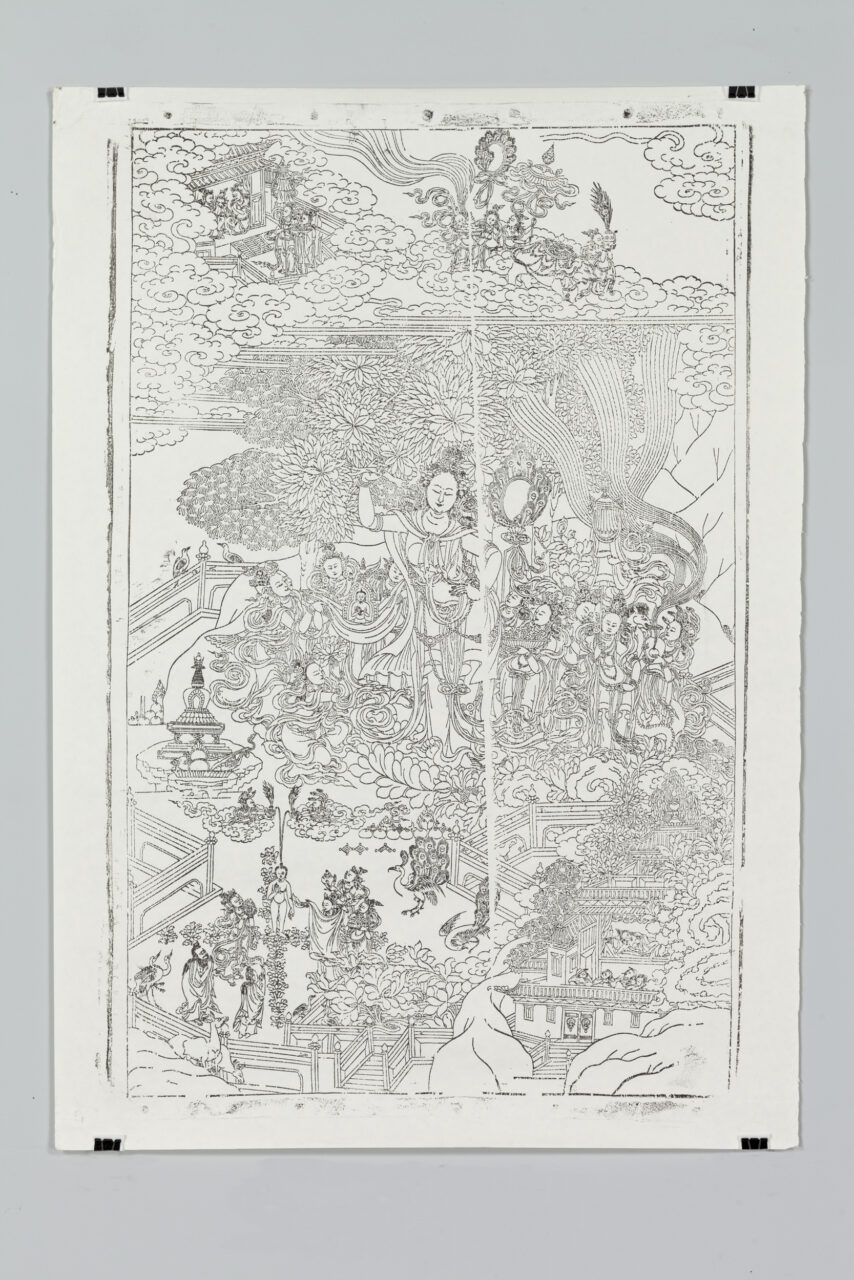

Painting from Printed Compositions

Objects in the Exhibition

18th century

Pigments on cloth

after 1960

Ink on paper

20th century

Pigments on cloth

Related:

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet consectetur adipisicing elit. Cum nihil placeat pariatur deserunt eius ullam incidunt maxime sunt ipsam. Ipsa, provident, laudantium, rem assumenda laboriosam veniam autem voluptas sint officia distinctio enim aut explicabo fuga animi voluptatum earum recusandae excepturi atque dignissimos iste? Exercitationem, praesentium eum. Harum ut maiores expedita exercitationem perspiciatis soluta aperiam dolores natus unde, sequi vitae debitis ex aliquam quas eum reprehenderit esse. Cumque amet et earum necessitatibus, repellendus ullam ducimus corporis architecto culpa placeat eum odit cum iure illo vitae rerum! Ullam et suscipit culpa? Eos voluptatum laudantium iste vero impedit adipisci maxime magni natus voluptatibus.

Sign up for our emails

Get the latest news and stories from the Rubin, plus occasional information on how to support our work.