Welcome to an online look at the Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art’s Patron and Painter: Situ Panchen and the Revival of the Encampment Style. This exhibition traces the founding and revival of the Encampment painting style of the Karma Kagyu School of Buddhism, as well as the career and artistic legacy of one of its greatest teachers, Situ Panchen Chokyi Jungne (1700–1774).

Precursors to the Encampment Style Permalink

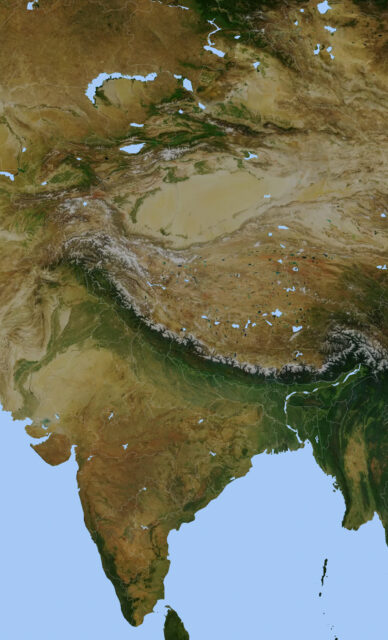

The Karmapas are the successive heads of one of the main lineages of Tibetan Buddhism, the Karma Kagyu, and since the twelfth century have been considered some of the most eminent lamas of Tibet. As the Encampment painting tradition was born in the courts of these religious hierarchs, it is important to look at the paintings of early masters within their lineage to understand from where this new style came. Looking at the tradition of painting within this line of teachers also makes it clear that the Encampment style was a radical break from earlier Tibetan artistic movements, which had been firmly grounded in Indian and Nepalese aesthetics.

Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara (After Situ Panchen’s (1700–1774) set of Eight Great Bodhisattvas); Kham Province, Eastern Tibet; 19th century; pigments on cloth; Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art; C2008.9

Founding of the Encampment Style Permalink

According to Tibetan tradition, the Encampment style was established—or more likely codified—in central Tibet by the painter Namkha Tashi in the court of the Ninth Karmapa (1555–1603). He placed figures based on Indian models in landscapes inspired primarily by paintings of the Chinese Yuan and Ming courts. His first painting teacher, Konchok Phende of the Menri School, had already begun looking to Chinese models before the Encampment style was established. However Namkha Tashi and his successors carried the Chinese-inspired aesthetic revolution started by Tibetan painters in the mid-fifteenth century much further.

Ninth Karmapa, Wangchuk Dorje (1555–1603); Central Tibet; ca. 1590; pigments on cloth; Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art, Purchased from the Collection of Navin Kumar, New York; C2005.20.2

Situ the Artist Permalink

While the Encampment style was founded in the late sixteenth century, most of what we know about it is from its eighteenth-century revival. This revival was engineered by Situ Panchen Chokyi Jungne (1700–1774) in Eastern Tibet, whose artistic career is well documented in his autobiography and diaries.

Situ could paint in at least two different styles—Menri and the Encampment style—and was a keen observer of early masterpieces and different styles of painting. He was strongly motivated to cultivate, patronize, and preserve what remained of the Encampment style, the painting tradition of his own now-endangered religious school. Three paintings attributed by inscription to Situ Panchen’s own hand have been brought together for the first time in this exhibition.

The Life of Situ Panchen Permalink

Situ Panchen was born in Derge, a small but culturally significant kingdom at the heart of the eastern Tibetan province of Kham. He grew up there in relative peace and prosperity, in what was otherwise a volatile period in Tibet’s history.

A watershed in his religious, artistic, and political career took place in 1729 with the founding of his new monastic seat, Palpung Monastery, which became the artistic hub for the revival of the Encampment style. In 1733, with the sudden death of his teachers, Situ Panchen was thrust at the age of thirty-three into the role of de facto regent of his school. Situ proved to be a brilliant scholar and charismatic leader, influential in many areas of cultural and institutional life in eighteenth-century Tibet.

Situ Panchen (1700-1774); From a Palpung set of Masters of the Combined Kagyu Lineages; Kham Province, Eastern Tibet; late 18th century, ca. 1760s; pigments on cloth; Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art, Purchased from the Collection of Navin Kumar, New York; C2003.29.2

Sets: Situ’s Greatest Legacy Permalink

Some of Situ Panchen’s most important and prominent artistic legacies are the multi-painting sets that he designed, many of which are still copied to this day. Among these only six were mentioned in Situ Panchen’s autobiography as his own commissions. Six other sets of paintings have been identified in this exhibition using other written sources or on the basis of stylistic similarities with the first six. These similar details include the unusually diminutive depiction of figures in landscapes, and miniaturist treatments of trees, buildings, palaces, and courtyards.

Situ reminisced that through the paintings that he designed and commissioned the artistic traditions of his native Kham were beginning to shine again, and he clearly made efforts to revive and maintain the traditions of his home province.

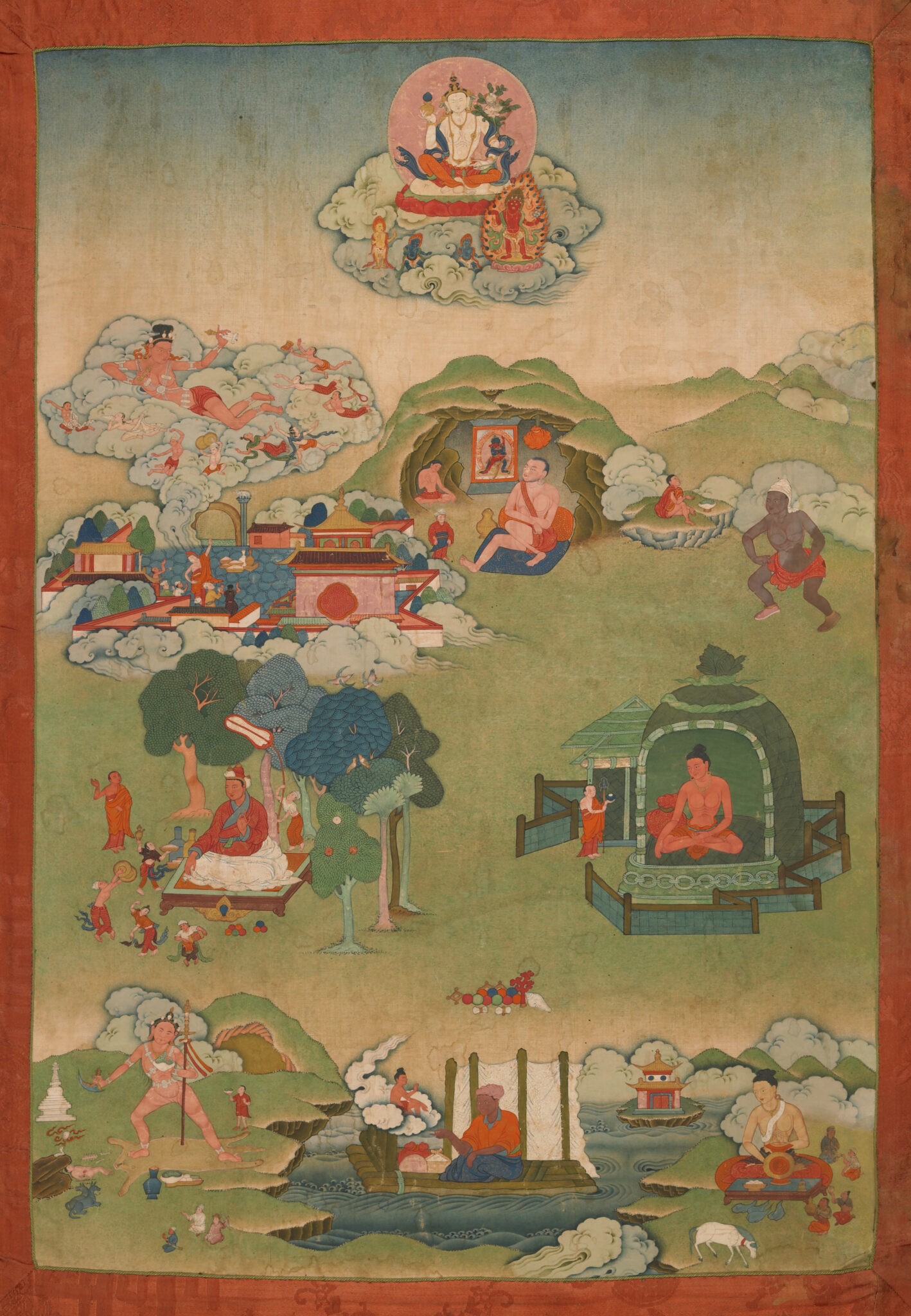

Situ Panchen as Patron of the Avadana Set, After Situ’s set of The Wish-granting Vine Series of One Hundred and Eight Morality Tales; Kham Province, Eastern Tibet; 19th century; pigments on cloth; Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art; C2002.27.5

Sets of the Mahasiddhas Permalink

In 1726 Situ painted one of his most striking and highly appreciated sets of paintings, the Eight Great Tantric Adepts (Mahasiddhas). It is the first set that Situ is recorded to have painted and marks the beginning of his public life as an artistic and religious leader. He offered this set of paintings to the king of Derge as he formally requested permission to build a new monastery at Palpung.

Situ reported in his autobiography that he painted this set “in a manner like the Encampment style” and did the sketching, coloring, and shading himself. Situ’s depictions of these eight great adepts have been variously arranged and combined in nine-painting, five-painting, and three-painting sets, as well as in single paintings.

Eight Great Tantric Adepts (From a Pelpung Monastery eleven-painting set of The Eighty-four Great Tantric Adepts); Kham Province, Eastern Tibet; 19th century; pigments on cloth; Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art, Purchased from the Collection of Navin Kumar, New York; C2005.22.1

The Masters of the Kagyu Lineage Set Permalink

This great set of lineal guru portraits was one of the most important of its kind, acting as a focus of devotion for all of its followers. It was the duty of later generations to commission paintings that would bring the set up to date by adding their own gurus and any other missing transmitters.

Among the various Palpung sets of Situ’s time, this has a certain “pre-Situ” flavor. The painters were presumably from Karsho, and they were, in part, copying older models. These artists also worked within their own Kham-based Encampment style, which existed in Karsho before, and continued to exist after, Situ’s time. Though not completely replaced by Situ’s new Encampment style, its painters could hardly have escaped the influence of his activities.

Karshö Karma Tashi; Thirteenth Karmapa, Dudul Dorje (1733-1797); Pelpung Monastery, Kham Province, Eastern Tibet; 18th century, ca. 1760s; pigments on cloth; Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art, Purchased from the Collection of Navin Kumar, New York; C2005.20.1

The Eight Great Bodhisattvas Set Permalink

In 1732 Situ Panchen had the artist Thrinlay Rabphel of Karsho trace and sketch some older paintings of the eight great bodhisattvas originally painted by Konchok Phende. Konchok Phende was a prominent painter who had been active in the sixteenth century as a court artist for the Ninth Karmapa and teacher of Namkha Tashi, founder of the Encampment painting tradition. That same year Situ also set up a workshop of artists from Karsho and had these tracings painted. Not only does this set indicate what kind of models Situ selected in his revival of the Encampment style, but it also bears witness to the existence of strong Chinese figural and compositional elements in pre-Encampment painting in the court of the Ninth Karmapa.

Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara (After Situ Panchen’s (1700–1774) set of Eight Great Bodhisattvas); Kham Province, Eastern Tibet; 19th century; pigments on cloth; Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art; C2008.9