Our website reflects the Rubin’s new chapter as a museum without walls, serving people around the world in innovative and exciting ways. Some pages from the previous website no longer exist or have moved.

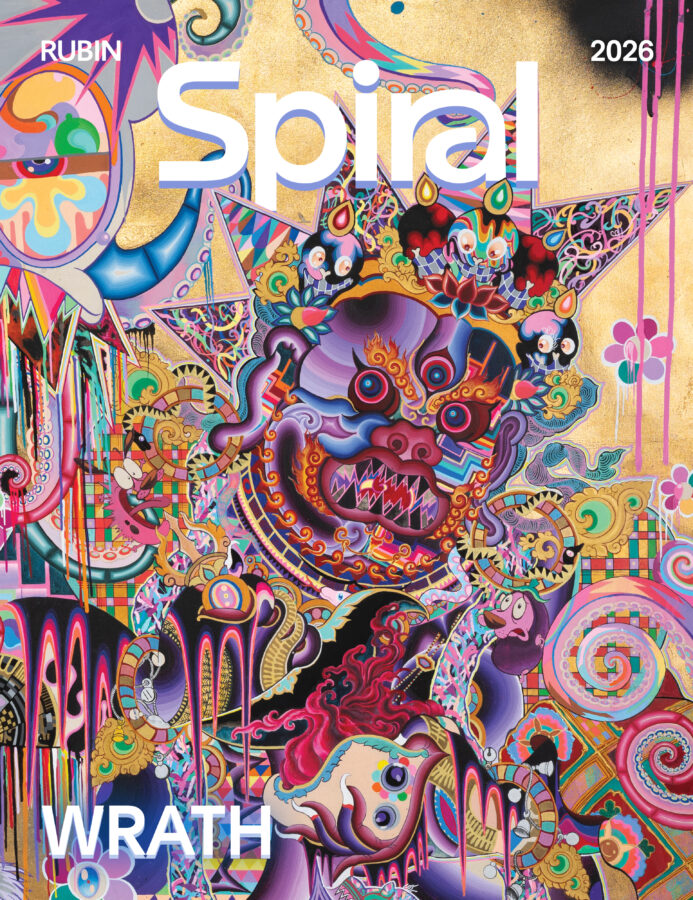

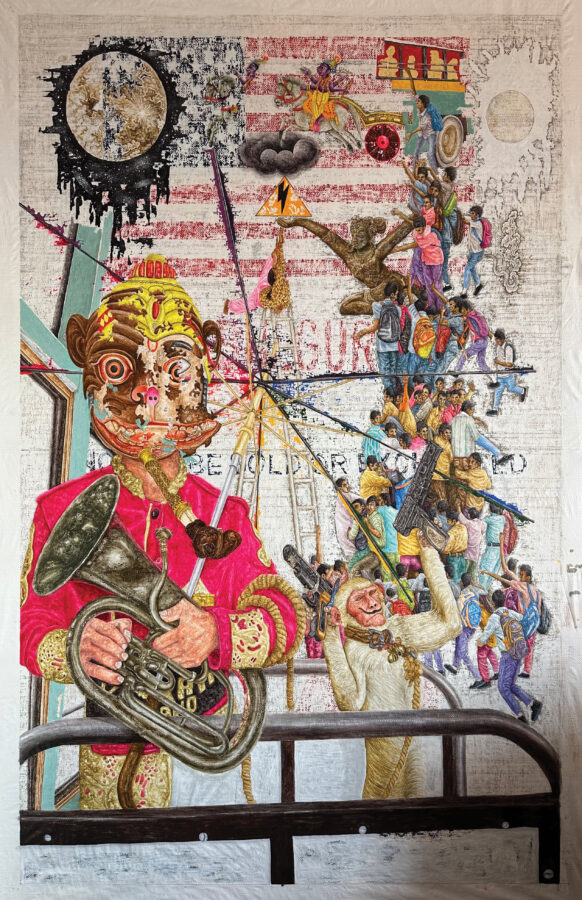

Visit Spiral or follow the links below to read, watch, and listen to engaging content on topics at the intersection of art, science, and Himalayan cultures.