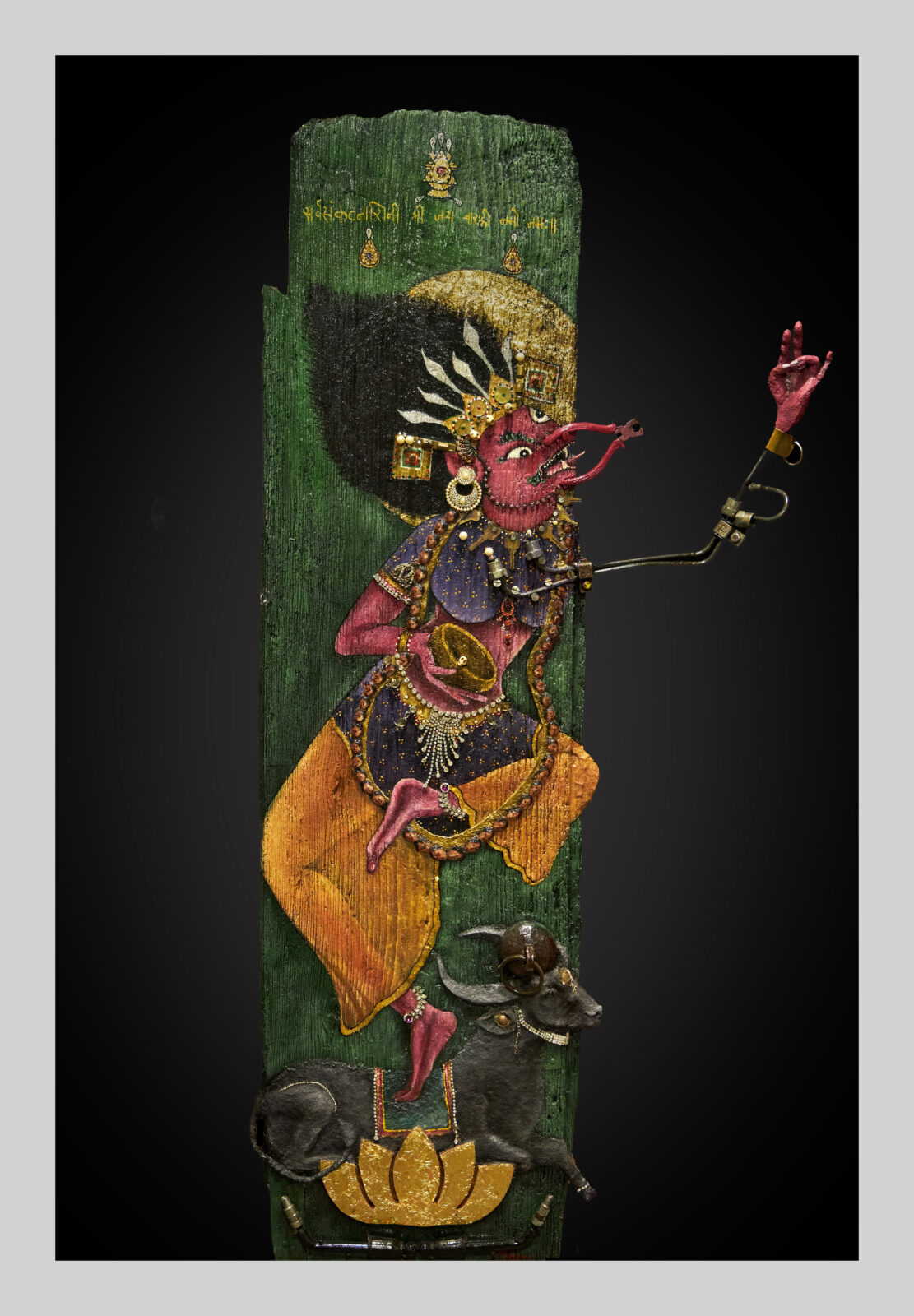

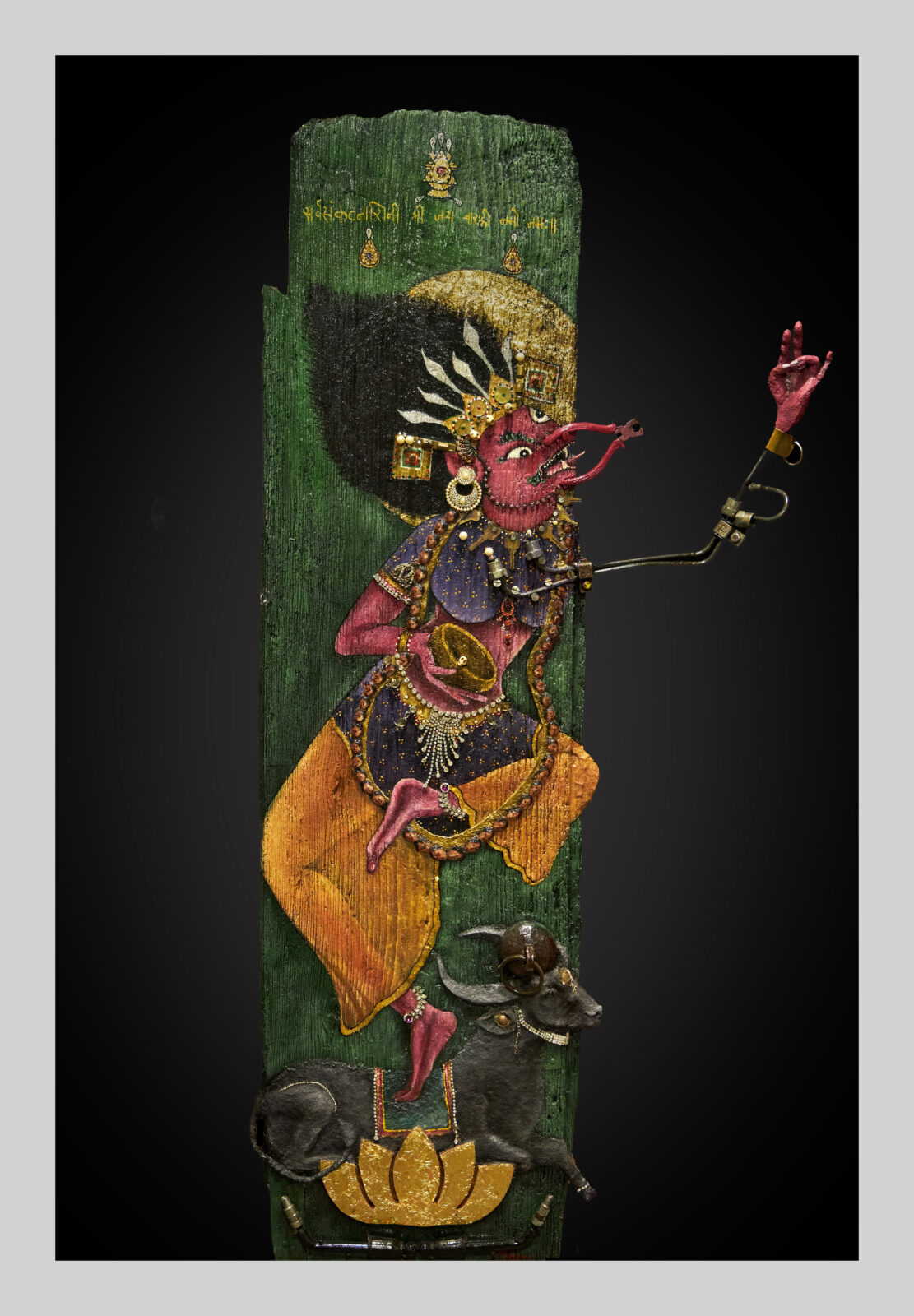

Meena Kayastha (b. 1985, Bhaktapur, Nepal; lives and works in Bhaktapur, Nepal); Goddess Varahi; 2023; traditional Nepalese door, papier-mâché, pliers, nails, coins, keys, jewelry, bell, discarded vehicle metal parts; courtesy of the artist

Meena Kayastha (b. 1985, Bhaktapur, Nepal; lives and works in Bhaktapur, Nepal); Goddess Varahi; 2023; traditional Nepalese door, papier-mâché, pliers, nails, coins, keys, jewelry, bell, discarded vehicle metal parts; courtesy of the artist

Reimagine: Himalayan Art Now presents artworks by thirty-two contemporary artists, many from the Himalayan region and diaspora, juxtaposed with objects from the Rubin Museum’s collection. Co-curator Roshan Mishra interviewed artist Meena Kayastha about attachment, non-attachment, and perspective shifting in the context of her art.

Meena Kayastha: Non-attachment is not about the non-acceptance of life; instead, I feel it is about understanding our very existence, being minimalistic, and appreciating what life offers us. In both Hindu and Buddhist terms, non-attachment, for me, reflects the profound way in which we, as human beings, approach life. For me non-attachment as an individual involves leaving greed or desire for material possessions or other things. Letting go of such attachments is challenging for all of us, as true freedom lies in releasing these ties.

In my interpretation, non-attachment serves as a guiding principle that encourages me to explore life with a more joyful approach, especially when I engage in my artwork. During this creative process, my subconscious mind naturally takes me into a zone where I am detached from emotions such as love, greed, and hatred. This detachment allows me to truly explore and discover my ideas within myself. Therefore, when I spend time in my studio, I am exploring a very core part of myself.

As an art practitioner, I explore non-attachment through various mediums, expressing the impermanence of life and the momentary nature of human experience. I use discarded materials in my art; they have often lost the attachment from their original purpose, and usually I find they have no existence of belonging. But somehow, when I bring them to my studio and start feeling that material and see it as a potential art form, I sense attachment, as if it belongs to me and I belong to it. This process invites me to see it as more than a discarded object.

As an artist, I use symbolism, forms, shapes, and other visual elements to convey the idea of letting go and embracing the present moment without worrying about the future.

Two-sided Festival Banner of Varunani and Varahi; Nepal; 17th or 18th century; Pigments on cloth; Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art; C2007.19.1

Feeling stuck or lost while making art is a common experience for many artists. Reframing your perspective can help break through creative blocks and open up new possibilities. As artists, we do many things when we feel stuck. For me, taking a break is the most sensible thing to do; it reenergizes me. That break doesn’t mean that I go back to the same artwork after taking the break. Sometimes I start a new work with a fresh approach. When I do this, it helps me retune my ideas, and often I learn from the new art piece, which may take me back to the old piece again.

Sometimes I just go to gym, which helps me cleanse, polish, and reframe my ideas. Usually a short walk after exercising helps a lot. As I am a multimedia artist, when I am stuck, I try to experiment with different mediums. Junk is my primary medium, but I also paint, sketch, and work with ceramics. These times allow me to explore other forms of art. Experimenting with new materials can spark inspiration and bring a different energy to my creative process.

Meeting an artist friend, seeking feedback, going to a gallery, or attending a talk also help me when I drift away from the work I have started but not been able to complete. Occasionally I help my husband, who is a photographer, and I get engaged with his activity too. But whatever happens, I always keep at the back of my head that feeling stuck is a natural part of my creative journey. I do believe that I need to get stuck because it retunes and reframes my original perspective. Mostly, if I can break through this moment, I can rediscover myself with new narratives and interpretations.

My paintings, junk art, and ceramic works serve as expressive mediums that aim to ignite curiosity; therefore, it reframes the perspectives of viewers. Through vibrant colors, intricate and abstract details, and innovative use of materials my paintings invite contemplation and self-examination. The various textures, elements, materials, and papier-mâché incorporate conventional concepts of beauty and value, encouraging viewers to find art in the discarded. I want to make the tactile and sculptural nature of my ceramic pieces engage the senses of the viewer, offering a tangible connection to the creative process.

My art often conveys cultural narratives and emotions; therefore, I think it creates dialogues to share experiences. Through this shared connection, viewers may find resonance in the stories embedded in the pieces by taking them to a deeper understanding of their own perspectives and the broader human experience. I believe that my work is a reflection of my culture, traditions, and the myths I grew up with. Therefore my art doesn’t only repurpose waste and discarded objects, I think it also narrates my upbringing and cultural roots, motifs, and elements. This allows my viewers to understand my contemporary interpretation of these expressions.

Meena Kayastha is committed to raising environmental and sustainability awareness by turning discarded materials into meaningful works of art. Her work is concerned with the dichotomy between women in Nepal being treated like second-class citizens and images of goddesses being worshiped. She compares debris—thrown away or sold for a cheap price with no regard for its life or the purpose it once served—with the treatment of some Nepalese women.

Her artistic process involves using scrapped objects and materials such as metal, wood, old doors, broken toys, and other electronic and industrial waste, transforming disregarded things into powerful storytelling tools. This interactive approach prompts contemplation of our relationship with objects and the transformative power of creativity.

She received a bachelor’s degree specializing in sculpture from Kathmandu University, Centre for Art and Design in 2007.

Roshan Mishra is the director and curator of Taragaon Museum and a Kathmandu-based visual artist. He is in charge of the Nepal Architecture Archive (NAA), which is run by the Saraf Foundation for Himalayan Traditions and Culture, a patron organization of the Taragaon Museum. Roshan is the founder of the Global Nepali Museum and Nepalian Art, and he initiated the Mishra Museum. He is currently a visiting faculty member at the Kathmandu University.

Get the latest news and stories from the Rubin, plus occasional information on how to support our work.