A.J. Jacobs:

I started this tradition of a secular prayer.

Devendra Banhart:

Journalist and author of many books including Thanks a Thousand: A Gratitude Journey, A.J. Jacobs.

A.J. Jacobs:

And what I would do is before every meal with my family, I would try to thank some of the people who made that meal possible. So I would say I’d like to thank the farmer who grew this tomato. I’d like to thank the woman at the supermarket who rang it up at the cashier box. And one day, my son, while I was doing this, said, you know, that’s fine dad. But it’s also kind of half-assed. Those people aren’t here. They can’t hear you. If you really were committed to this idea, you should go and thank them in person.

I honestly think I could have thanked 500, 5,000, a million. I could have probably gotten to most of the eight billion people in the world if I had really tried.

Devendra Banhart:

Welcome to season 5 of AWAKEN, a podcast from the Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art about the dynamic path to enlightenment and what it means to “wake up.”

I am Devendra Banhart, singer, songwriter, artist, and your host. In this season, we hear from experts in the realms of art, social science, Buddhism, and more to better understand how interdependence is the foundation of every aspect of our lives.

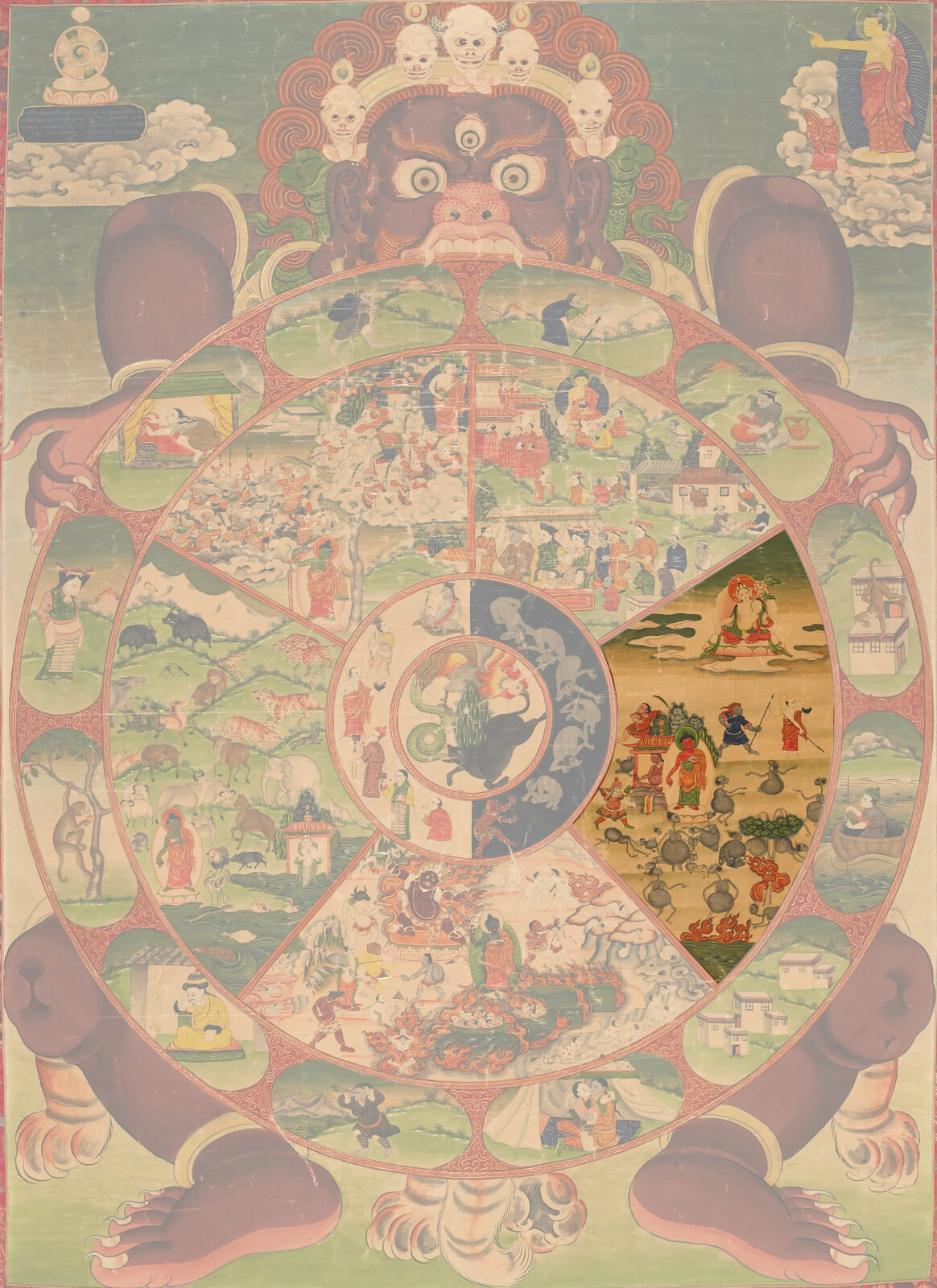

Himalayan art has long been a pathway to insights and awakening, and over the course of eight episodes we look specifically at a painting of the Wheel of Life to see what it can teach us about the interconnected nature of existence.

Throughout this journey, we’ll discover how greater awareness of our interdependence can be the wake up call that motivates us to take actions for a better world.

In this episode we’re looking at community on a large scale—all the people you’re connected with, entangled with, even if you don’t know them all personally.

So back to A.J. Jacobs’s story. A.J. wanted to find ways to be more grateful, a term he sees as somewhat interchangeable with interdependence.

A.J. Jacobs:

To me, that’s what “thank you” means is I acknowledge my interdependence with you, and I appreciate it. And I’m grateful for it.

Devendra Banhart:

So he started with one of the most cherished moments of many people’s day.

A.J. Jacobs:

I committed myself to this project where I spent months going around the world trying to thank everyone who had anything to do with my morning cup of coffee.

Nicholas Christakis:

The cup of coffee example, it’s used to describe the modern economy because there’s no single human being who’s capable of all the requisite skills to produce a cup of coffee that you take for granted in the morning.

Devendra Banhart:

Professor Nicholas Christakis is a social scientist and physician who conducts research in the areas of social networks and biosocial science and directs the Human Nature Lab at Yale University.

Nicholas Christakis:

It’s a product of these complex global markets.

A.J. Jacobs:

I buy my coffee at a coffee shop on the upper west side of New York where I live. And I went in there and first person I encountered was my barista. And I decided I was going to thank her, not just like reflexively thank her, but look her in the eyes and say thank you. And it was an odd experience because she said, thank you for thanking me.

Devendra Banhart:

That was just the beginning because as A.J. Jacobs knew and Nicholas Christakis illustrates here:

Nicholas Christakis:

There’s nobody that knows how to farm coffee beans, how to roast coffee beans, how to transport coffee beans, how to grind coffee beans or build the grinder for the coffee beans. How to manufacture styrofoam, how to form styrofoam into cups. How did the truckers that drive the cups to the baristas operate? The cash registers design the computer systems that manage the orders? It’s, it’s a reflection. This ability to purchase a cup of coffee is a reflection, it is said of this global interconnected economy that we now have.

A.J. Jacobs:

When I decided to thank everyone who had anything to do with my morning cup of coffee, I knew there were some people I had to thank, you know, the barista and the farmer and, and the truck driver who drove the beans. But once I started to think about it, I realized I could go much farther than that. Maybe I took it too far, maybe I went, but I don’t think so because everything is interconnected. So when I thanked the person who drove the truck with the coffee beans, I realized he couldn’t have done his job without a road. So I had to thank the people who paved the road, and maybe even the person who drew those yellow lines in the middle of the road so the truck wouldn’t go into oncoming traffic. And I just took it as far as I could, but that’s not even far enough because I thanked a thousand people, and the reactions were interesting because some people were confused, but most of them were actually very grateful.

Devendra Banhart:

Thanking a thousand people turned into A.J. Jacobs’s bestselling book, Thanks a Thousand, and a TED Talk which has been viewed three and a half million times.

A.J. Jacobs:

I’ll just give you an example that I didn’t really go down, but for instance, the truck driver told me the way he stays awake is by listening to music. I said, what kind of music? Oh, I like Beyonce. So I think I did try to call Beyonce and thank her, she didn’t return my call, which is okay, she’s busy, but she could not be doing her job without the microphone, without the people who make the musical instruments. They couldn’t do their job without the people who mine the metal. Those people couldn’t do their job without the folks who make the productive equipment. They couldn’t do their job without the computers they use to design it.

Devendra Banhart:

Again, Nicholas Christakis.

Nicholas Christakis:

From a more network point of view, what’s helpful to understand is this thing called the small world’s property. This notion of six degrees of separation, which is a famous experiment done by Stanley Milgram in the 1960s, where he gave a group of people in the center of the country letters, and he asked them to arrange for these letters to go, I think, to a stockbroker in Boston was one of the targets. And these people obviously didn’t happen to know this stockbroker, but they could pass the letter to someone they thought might be closer to the stockbroker. So maybe they knew, maybe their cousin lived in Providence, Rhode Island. So they figured, well, if I send the letter to my cousin in Providence, Rhode Island, maybe that, that’s closer to the Boston stockbroker.

And then the Providence, Rhode Island cousin gets the letter and says, I don’t know anyone in Boston, but I, but I know a stockbroker here in Providence. Let me give it to him. And then the letter goes to the Providence stockbroker, and the stockbroker goes, well, I know a stock, I don’t know this stockbroker in Boston, but I know another stockbroker in Boston, so I’ll send the letter to him. And then that last person, now we’ve come to four steps, says, yeah, I know this Boston stockbroker, and hands it to that person. And then what Milgram did is he took all the letters that arrived at the stockbroker, and he saw how many hands did the letters traverse before they got to the target, and of the letters that got there, and not all of them did, it was about six hops.

And this led him to the famous six degrees of separation. And it turns out that this is a kind of global property actually, of the worldwide network that actually each of us is maybe six hops from anyone else. You could pick, pick almost anyone on the planet. And through a sequence of steps on average, we are six hops from that person. So that’s a property of global worldwide networks of human beings.

Devendra Banhart:

This experiment was recreated more recently. And still, many decades later, and with two billion more people on the planet, we continue to have just under six degrees of separation from each other.

Back to A.J. Jacobs.

A.J. Jacobs:

I often think about this story and a book called Invisible Cities by Italo Calvino, a beautiful book. And he has, one of the imaginary cities he came up with was a city where all of the apartments have strings that go across the street or down the block to other apartments. And there are different colors. So one color means that you’re blood related, another color means you’ve worked together, maybe you’ve dated. And he described that city as just a thick web of threads all coming together. And that’s kind of the way I see our world. We are covered in this thick, thick blanket of threads that connect us all in multiple hundreds of ways.

Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche:

Buddha said we all are connected with the so many different labels.

Devendra Banhart:

Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche is a renowned meditation teacher, author of several books on Buddhism, and head of the worldwide Tergar Meditation Community.

Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche:

Even though we are never met and we are the opposite of the Earth, still we are connected. The negative example is there’s Covis comes into one city soon go out entire world. So there’s the power of interdependent. The Buddha give one simple example that if we want to plant a tree, then what we need first, soil, water, sunlight, air seed, fertilizer, all these things, oh, so many pieces there. And each one require so many subgroups, maybe a person, the environment, the situation, the time, so many things there. And then we need to connect all of them together. So if you put the water in the east, soil in the south, sunlight in the west, seed in the north, the apple tree cannot grow. So you mix all this together, the connection. So then once we make connection, you have to wait. And then, they walk together and then the spark, tiny spark coming and then grow and bigger, bigger, bigger, bigger. Then one day you have flower, then you have the apple. So that’s the result of interdependent.

Devendra Banhart:

Mingyur Rinpoche reminds us that nothing exists independently. And although we make distinctions between different things to try to understand our world, when looked at from a Buddhist perspective, there is no real separation, all of it is, well, interconnected. Again A.J. Jacobs.

A.J. Jacobs:

It’s a reminder that you cannot do anything yourself. We live in a society which requires the cooperation of millions, billions of people.

I talk a lot about how the exterior affects the interior and not just the other way around. That your behavior affects how you think and feel. And so if you act in a grateful manner, if you act as if you’re grateful, even if you’re not feeling it, you start to become more grateful. And if you act as if you’re confident, you become more confident. And that actually ties into this idea of interdependence, that our actions and our emotions are more interdependent than you would think. It’s not a one-way street, and they’re not two separate things. They are two intertwined phenomena.

I wrote a book a few years ago about the global family and how we are all related. That idea of the human family, it’s not just a cliche, it’s true. And now because of science, because of DNA, you can see how you’re related to almost everyone on earth. So I love looking around. Even if someone cuts me off or someone is rude to me, I try to remember, you know what, they’re probably my 16th cousin three times removed, so maybe I should have a little compassion for them. That’s what my 17th great-grandfather would want. And grandmother.

Devendra Banhart:

Being aware of our interconnectedness can remind us to make better choices in the way we treat each other.

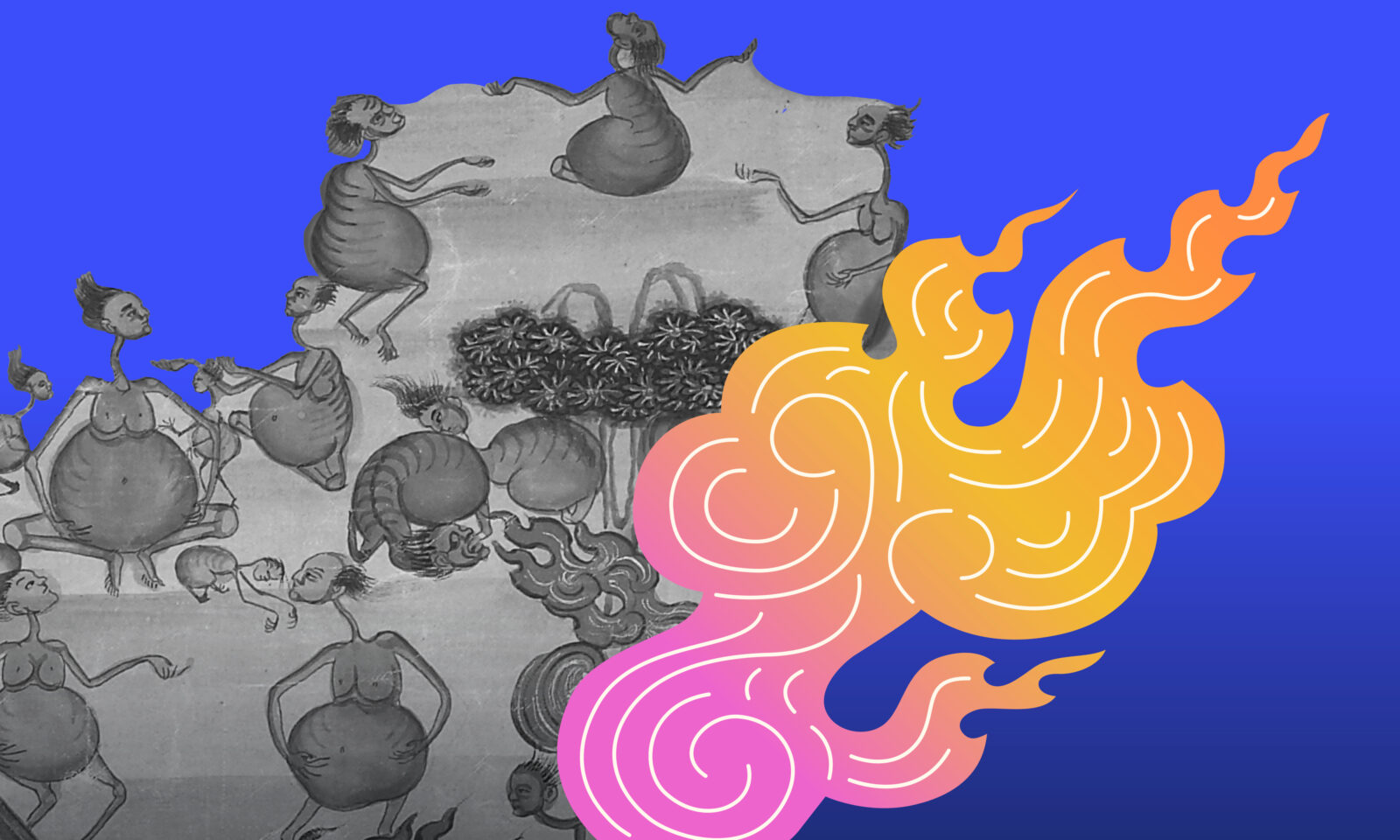

This season we’re focusing on a painting of the Wheel of Life in the Rubin Museum’s collection. The Wheel of Life, also known as the Wheel of Existence, is a foundational symbol in Buddhism and offers a visual representation and reminder of the cycle of life, death, and rebirth. Part of the wheel depicts the six realms of existence where it is possible to be reborn. To see the artwork in detail, go to rubinmuseum.org/wheel.

Here, professor Annabella Pitkin, who teaches Buddhism and East Asian religions at Lehigh University, talks us through the hungry ghost realm.

Annabella Pitkin:

One of the places that a consciousness can transmigrate after death in a particular realm, where propelled by the consequences, the karmic, the ethical consequences of stinginess, selfishness, miserliness, hoarding resources, refusing to give them to others, refusing to share greed, endless insatiable, addictive greed, and refusal to allow others to have any of what one has that produces a state, which is the hungry ghost state, in which the individual experiences an enormous insatiable hunger, this empty belly, but they can only put food and drink inside through this tiny brush stroke neck, this tiny little mouth.

And so they cannot satisfy their hunger. And this agony of unsated thirst, unsated hunger, this is the experience, the consequence of greed and selfishness, and abandoning others when the others have need of one.

And that speaks very directly to a number of concerns that we might experience in our own lives. On the one hand, it’s a very strong ethical teaching about the centrality of acting in an ethical way, with an awareness of interdependence in one’s own micro community, in which one should share and give generously to everyone that one comes in contact with one’s loved ones, and also people that one may not know very well, even strangers, and even people that one might temporarily be experiencing as one’s enemy. They all are appropriate recipients of our generosity, and we don’t wanna become hungry ghosts.

And on the other hand, again, this painter has chosen to mix in a little bit of hope. So we see these gray hungry ghosts, and we also see some flames at the bottom of the image. And we see a demonic gray figure with a pointy stick wearing a dark blue tunic with a white belt in the middle of the frame, sort of reddish, flaming hair perhaps. So there’s a demon who’s kind of the boss of this scary realm. But we also see with reddish skin and monks robes, the Buddha standing up in a halo of light, clearly here to teach about generosity, love and kindness and interdependence to this assembled crowd of hungry ghosts. And we see in the sky above a cosmic buddha figure with white skin and a halo, and red and green silken draperies, and sitting on a lotus throne in a realm of clouds.

Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche:

1998, first time I come to the USA, I have a lot of interest about the brain that I discussed with the neuroscientists.

Devendra Banhart:

Again, Mingyur Rinpoche.

Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche:

That time they thought maybe that’s one special area in the brain that controls everything. But of course later they cannot find. And I wrote in 2008 in my book, The Joy of Living, what I call it the missing conductor. So what they said is all the neurons works as like there’s a conductor, but they cannot find a single conductor, all this part of brain independently, they are connecting each other. They not just in the brain, in the heart. Now they find in the gut there’s a lot of neurons. So entire body is working together, interdependently. So I think it’s very important. Of course there is what we call multiplicity pieces, always there. But how this piece is connecting each other, that’s the most important part of thing that we need to explore.

Devendra Banhart:

The heart doesn’t stop pumping because it wants to preserve its resources. It’s always sharing, just as the lungs are, and the neurons. We can use this as a metaphor for how the world, how humanity, can and should work. Our well-being depends on us all working together.

Again Annabella PItkin on the hungry ghost realm in the Wheel of Life.

Annabella Pitkin:

The message of interdependent connection, generosity, mutual care, that message is being brought to them even as we speak according to this picture.

We all are trapped in a kind of less than ideal experience of ourselves in our lives much of the time. And one of the things that’s so radical about the Buddhist way of framing this kind of reflection and this kind of image is that precisely because the hungry ghost state is a self-inflicted state, a self-inflicted state of suffering, that comes from the choice to ignore interdependence and to focus only on selfishness and greed. Because it’s self-inflicted, it’s also possible to cure it through one’s own return to a recognition of interdependence and connection.

And that very much speaks to our global moment, to the resource rich abundance of the planet that we share, of the extraordinary web of cultures and capacities, and economies and technologies that we all share, that we inherit, and that we’re all creating together. There’s so much potential for abundance and we often experience our societies and our histories as taking us toward a state of selfishness and fear of fighting with one another over too little, and scarcity. And the painting suggests that that’s actually a cognitive error. Actually, our interdependent reality is an infinitely abundant one, in which we ourselves, through our recognition of our connection to one another, and through our recognition of our need to care for one another, the kind of inextricability of our care for self and other, that recognition is a recognition that heals and sets us free.

A.J. Jacobs:

I think we have gone way too far in the direction of individualism. I am a fan of individualism. I believe in individual rights, but I think that we’ve gone too far in that direction and, and have failed to acknowledge our interdependence. And we’ve become a society obsessed with the single superstar. Like, you know, you look at music it’s the one singer, the singer song. But really there’s many people who help make that music.

And as an author, I even felt this while writing my book, the author, that’s the one who has their name on the cover, they get all the glory. But that is so distorted because a book requires hundreds of people. We are a society obsessed with the sort of single hero, whereas in real life, everything takes not just a village, but the globe.

I’m trying to train my brain to remind myself that I can, I can be special, I can be unique, but still be a part of this vast, interconnected web, and that nothing in my life would exist without millions of other people. But I can still be special. It’s sort of that balance between the two.

Devendra Banhart:

Balance is everything. If we can make small changes, day by day, and acknowledge each other’s role in this magnificent tapestry of life, it will, as lofty as this sounds, make a difference in our world.

You just heard the voices of Nicholas Christakis, A.J. Jacobs, Annabella Pitkin, and Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche.

I am Devendra Banhart, singer, songwriter, artist, and your host.

To see the artwork discussed in this episode, go to rubinmuseum.org/wheel.

If you’re enjoying the podcast, leave us a review wherever you listen to podcasts, and tell your friends. For more stories and news from the Rubin, follow us on Instagram @rubinmuseum and sign up for our newsletter at rubinmuseum.org.

AWAKEN season 5 is an eight-part series from the Rubin.

AWAKEN is produced by the Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art with Kimon Keramidas, Gracie Marotta, Christina Watson, and Sarah Zabrodski in collaboration with SOUND MADE PUBLIC including Tania Ketenjian, Philip Wood, Alessandro Santoro, and Aaron Siegel.

Original music has been produced by Hannis Brown with additional music from Blue Dot Sessions.

AWAKEN Season 5 is sponsored by The Prospect Hill Foundation and by generous contributions from the Rubin’s Board of Trustees, individual donors, and Friends of the Rubin.

This program is supported, in part, by public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, in partnership with the City Council.

Thank you for listening.

We live in a world that requires the cooperation of millions, if not billions, of people. Even without knowing those people, they impact your life in countless visible and invisible ways—and vice versa. How can tapping into a greater awareness of those interconnections change how we operate in the world?

For centuries people have turned to the image of the Wheel of Life to better understand cause and effect and the very nature of existence. The section of the Wheel depicting the hungry ghost realm is the focus of this episode’s exploration of community.

This episode features journalist and author A.J. Jacobs. AWAKEN season 5 is hosted by singer, songwriter, and artist Devendra Banhart. Other guests in this episode include social scientist, physician, and professor Nicholas Christakis, professor of Buddhism and East Asian religions Annabella Pitkin, and Tibetan Buddhist meditation teacher and author Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche.

Complete our listener survey for a chance to win two free tickets to the Rubin’s Mindfulness Meditation program in person or online.

Wheel of Life, attributed to Lhadripa Rinzing Chungyalpa (b.1912, Sikkim–d.1977); Sikkim; c. 1930; pigments on cloth; Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art; C2004.21.1

One of the most important teaching tools in Tibetan Buddhism is the Wheel of Life, also known as the Wheel of Existence, which demonstrates the cyclical nature of life, death, and rebirth. The scenes within the wheel portray the laws of karmic cause and effect, illustrating how a person’s actions bring about positive or negative outcomes in their current and future lives.

This episode explores the hungry ghost realm. Those reborn into this realm have malformed bodies with huge, ravenous bellies but necks too narrow to accept food or water, leaving them forever hungry and thirsty. Their agony of unsatiated thirst and hunger is the consequence of greed and selfishness. The bodhisattva of compassion Avalokiteshvara presides at the top of this realm, suggesting that with the Buddha’s teachings it is possible to escape from the suffering.

Devendra Banhart is an internationally renowned musician considered a pioneer of the “freak folk” and “New Weird America” movements. Banhart has toured, performed, and collaborated with Vashti Bunyan, Yoko Ono, Os Mutantes, the Swans, ANOHNI, Caetano Veloso, and Beck, among others. His musical work exists symbiotically alongside his pursuits in the other fine arts including painting, poetry, and drawing. The Venezuelan American has released 11 albums. His drawings and paintings have appeared in galleries all over the world, including the Art Basel Contemporary Art Fair in Miami; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; Palais des Beaux-Arts in Brussels; Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles; Nicodim Gallery; and Serralves.

A.J. Jacobs is an author, podcaster, and human guinea pig. He has written four New York Times bestsellers that combine memoir, science, humor, and a dash of self-help. His most recent book is The Year of Living Constitutionally, and other books include The Year of Living Biblically, The Know-It-All, and Thanks a Thousand. He has told several stories on The Moth and given TED Talks that have amassed over 10 million views. He hosts The Puzzler With A.J. Jacobs, a daily podcast produced by iHeart media, in which he gives short, audio-friendly puzzles to celebrity guests. His popular Substack newsletter is called “Experimental Living with A.J. Jacobs.”

Nicholas A. Christakis, MD, PhD, MPH, is the Sterling Professor of Social and Natural Science at Yale University. His work is in the fields of network science and biosocial science. He directs the Human Nature Lab and is the co-director of the Yale Institute for Network Science. He was elected to the National Academy of Medicine in 2006; the American Association for the Advancement of Science in 2010; the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2017; and the National Academy of Sciences in 2024.

Annabella Pitkin is associate professor of Buddhism and East Asian religions at Lehigh University. Her research focuses on Tibetan Buddhist modernity, Buddhist ideals of renunciation, miracle narratives, and Buddhist biographies. She received her BA from Harvard University and PhD in religion from Columbia University. She is the author of Renunciation and Longing: The Life of a Twentieth-Century Himalayan Buddhist Saint, which explores themes of non-attachment and teacher-student relationship in the life of Khunu Lama Tenzin Gyaltsen. More →

Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche is a recognized tulku of the Kagyu and Nyingma lineages of Tibetan Buddhism, a teacher, spiritual leader, and bestselling author. He possesses the rare ability to present the ancient wisdom of Tibet in a fresh, engaging manner. His profound yet accessible teachings and playful sense of humor have endeared him to students around the world. Rinpoche’s teachings weave together his own personal experiences with modern scientific research in relation to the practice of meditation. He has authored several books including two bestsellers: The Joy of Living: Unlocking the Secret and Science of Happiness, which has been translated into over 20 languages, and In Love with the World: A Monk’s Journey Through the Bardos of Living and Dying. His recent TED Talk is titled “How to Tap into Your Awareness—and Why Meditation Is Easier Than You Think.” Rinpoche teaches extensively around the world and oversees dharma centers, including three monasteries in Nepal, India, and Tibet, and the Tergar Institute in Kathmandu; Tergar meditation communities on six continents; numerous schools in Nepal; and social engagement projects related to health, hunger, hygiene, the environment, and women’s empowerment issues in the Himalayas.

Get the latest news and stories from the Rubin, plus occasional information on how to support our work.