Photo: Ahmed Salahuddin/Nurphoto via Getty Images.

Photo: Ahmed Salahuddin/Nurphoto via Getty Images.

In ancient folklore, an alien was a being from another place, unfamiliar with the customs of the inhabitants it encountered. An engagement with the otherworldly triggered the imagination of writers, thinkers, and statesmen to conceive of and possibly even prepare for what was beyond their borders. Ironically, the times now are not very different, as people and governments have turned against their neighbors. The story here is graver still—a situation wherein they turn against their own people.

In statecraft, one always questions the very nature of authority, but also its location. Who wields power? Is it the vigilant citizen, regimes, activists from the field? Are the voices of those who have been disenfranchised or those who strategically deploy their power able to cultivate change for the better?

Resounding across the globe, after being released on bail in late 2018 following a 107-day incarceration in Bangladesh, one voice certainly stands out from the fray: the deep, meditative inflection of Shahidul Alam. He once stated, “There is no government I know that does not champion democracy and human rights in its rhetoric but also actively suppress both in its practice. It’s best to recognize that reality and work within it rather than fantasize some ideal solution that has no relevance to everyday art practice.”

For Shahidul and other activists, the everyday is perhaps the place of power, and as we have learned, everyone who now has the means of communicating across the planet through mobile devices should ideally be the voice of real power: plural, shared, and dispersed.

As images flicker across the multiscreens of our everyday lives, and as data sharing and mining become possibly the most empowering tools of our democracy, do we realize how and when we become affiliated to a political will, as well as when power is wrested from us?

Shahidul Alam, renowned photographer, pedagogue, writer, and curator, has countered rote opinions, opposed covert and guided elisions of secular expression, and revealed marginalizations and atrocities within his community. On August 5, 2018, he was arrested and imprisoned for voicing his reactions to civil injustices being protested by students who mobilized in the thousands across Bangladesh some months prior.

His wrongful incarceration and conditional release bring to light constitutional loopholes those in power use to mobilize laws such as Section 57 of Bangladesh’s Information Communications Technology Act, under which several citizens and media practitioners have been incarcerated and tortured for expressing their so-called antinational opinions. They have been deemed trespassers and troublemakers.

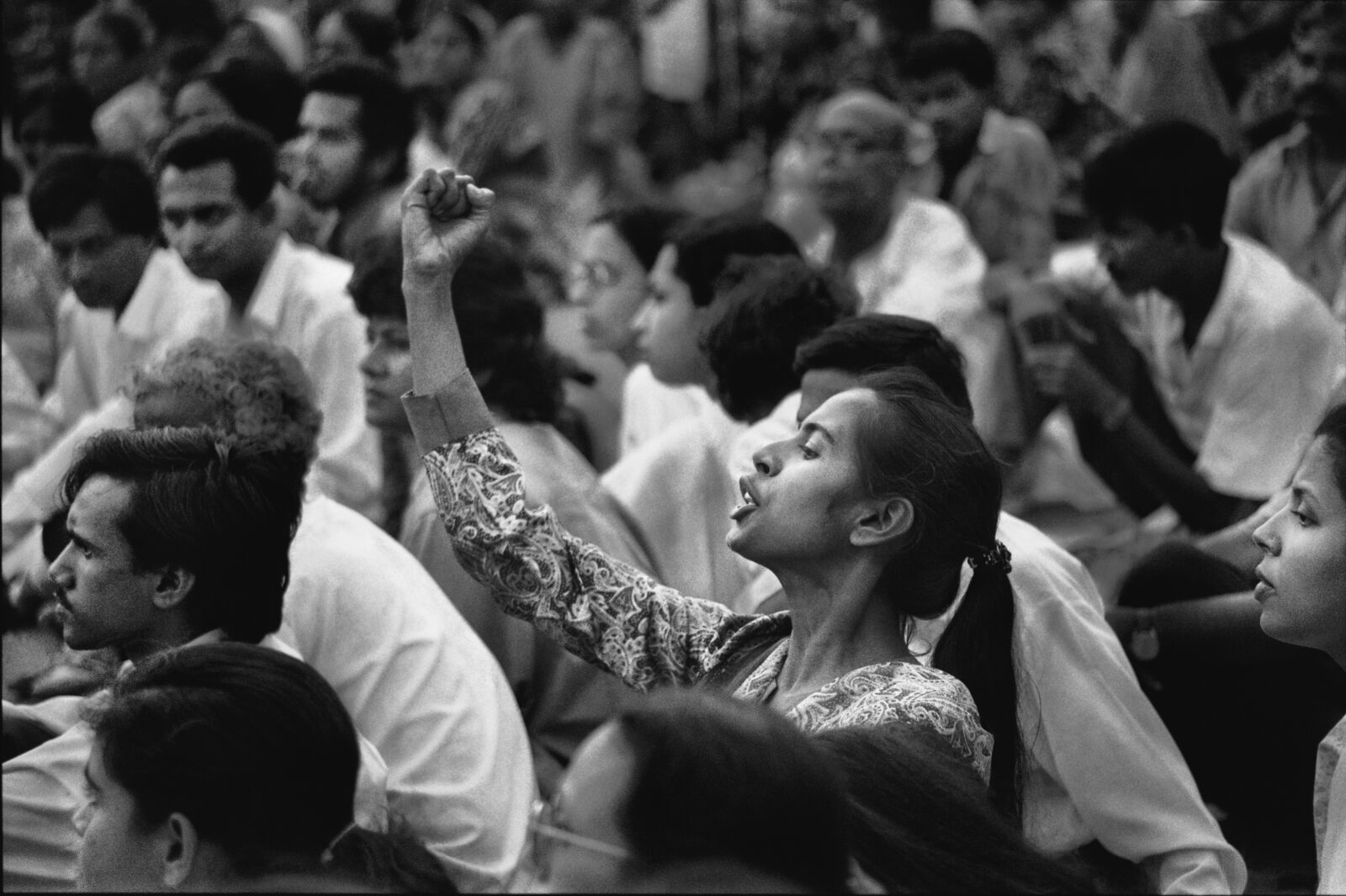

Azad attended political rallies with her sister when she was a child. As a singer and performer, she was involved with the women’s movement, the committee demanding the trial of war criminals, and the cultural group Charon Shangshkritik Kenro, which led to her joining Shommilito Shangshkritik Jote. As part of this group, she was active in the movement to bring down President Ershad. Here, Azad is pictured protesting at a rally at Shahid Minar.

Shahidul Alam (b. 1955, Dhaka, Bangladesh); Smriti Azad, Dhaka; 1994; photograph courtesy of Drik.

After founding both the Drik Picture Library and the Pathshala South Asian Media Institute in 1998, Shahidul established Chobi Mela, South Asia’s most influential photography festival, as well as Banglarights, an independent media platform for human rights in Bangladesh. Which is to say, there is a dynamic, poetic, and prophetic power in this moment, as Shahidul, as one of the masters of image-making in the world, has over the years galvanized the passionate articulations of an entire generation to think critically; to see well beyond the surface of an image or circumstance; and to always question every event, intention, context, and voice of the self and other. Having probed and exposed homogenizing tendencies across social spectrums by cross-examining cultures in conflict, he has championed the individual as an unwavering, energized force and personal disclosure as a profound political tool.

His pictures, like many of those now coming from the street, present an image of a world that seems to be turning against itself and hence others too. As a consequence, nothing becomes more elusive than our association to place, and hence, nothing more contentious than the laws that seek to govern our actions therein. As controllers of our own image, are we slowly defined by them, covertly or by the viewers who follow us? Can we ponder what the collective will of the afterlife of an image will be? At a time when fabricating situations and reframing memories through staged images proliferate, the risks and ethical implications of circulating images makes us also revisit the claims of news-gathering processes. Who is to be trusted? Shahidul suggests that everyone can and must act ethically to set the barometer right.

As political pogroms surrounding identity issues force the world into binaries yet again—as religion, caste, or class in coded and overt ways enforce xenophobic insecurities or induce a depraved form of ritual cleansing—Shahidul’s life clearly denounces a growing societal malaise by speaking to and of vibrant lived testimonies that function as counterarguments, making transparent rampant authoritative motives. His work activates a sense of multiculturalism that is carefully and poignantly deployed as a parallel dimension through mounted international exhibitions like Women of the Naxalite Movement and Everyday Life in Bangladesh and publications such as People’s War, Birth Pangs of the Nation, and My Journey as a Witness. He tackles transnational issues with a symbolic energy through head-on debates with notions of sovereignty, authenticity, and even civilization.

In 2017, Shahidul presented the exhibition Embracing the Other, looking at ways we can recalibrate the debate on radical Islam by considering the everyday life of devotees. It focused on one particular center of learning, the Bait Ur Rouf Mosque. In his words, “What I want to do through this work is to establish that Islam (and pretty much all religions) by and large, provides a moral compass for our navigation. There are large magnets around that have changed the direction of our compass. I want to return to the original direction and to remind people that it is the carriers of these magnets, both within and outside, whom we need to challenge. It is not Islam we need to fear, but the weapons industry and those who control it.”

Questioning stereotypes by exposing local histories and personal narratives has been a constant, provocative refrain in his work, enabling him to examine tolerance in contemporary South Asia. His photography and poetry present interlinked propositions for the need for fusions at a societal level by using visual reminders and metaphors around appropriation and occupation. It is this very ethics of discontentment—ideological affinities and strategies resulting from constitutional stalemates—that he emphatically deploys for bearing witness at home, even his own home from which authorities forcefully and secretly captured him.

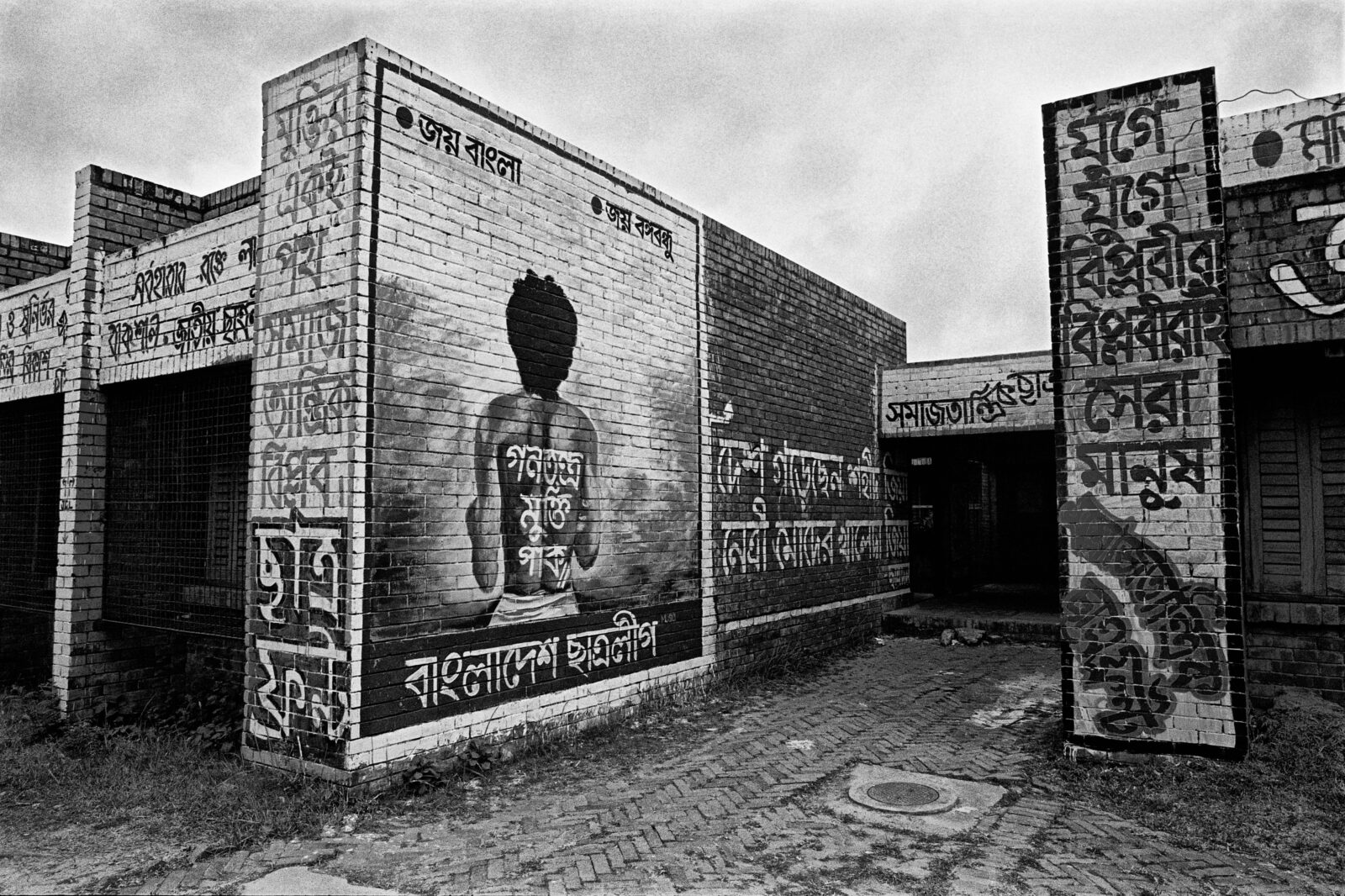

The situation at hand also brings into focus an exhibition he produced in 1987, A Struggle for Democracy, which spoke of the pangs of a nation on the precipice of change, including the death of activist Nur Hossain that led to free elections in 1991. Yet the terror, genocide, civil unrest, and devastation and uprooting of entire communities continues to unfold. While many stories of suffering are simply never told, Shahidul’s work preempts a new wave around the iconography of activism, with the production of new visual testimonials and fearless inscriptions of injustices, as his own students are now everywhere, and his institutions stand strong. Our thoughts remain with Shahidul who has shown us, once again through his own predicament, the agonized erasures and absences that are being imprinted on the collective memory of people everywhere.

On November 10, 1987, the opposition parties in Bangladesh tried to stage a siege of Dhaka in an attempt to oust President Ershad. Noor Hossain was a young worker who came out in the streets to join the protest. He had painted “Let democracy be freed” on his back, and police shot him. The mural on the walls of Jahangirnagar University on the outskirts of Dhaka is dedicated to him.

Shahidul Alam (b. 1955, Dhaka, Bangladesh); Noor Hossain, Dhaka; 1990; photograph courtesy of Drik.

Through his thesaurus of clues we find evidence of other lives that now capture our undivided attention, such as Kalpana, who was only twenty-three when she was abducted after making her life’s mission to campaign for the rights of the indigenous people living in the Chittagong Hill Tracts. In 2016, Shahidul mounted an exhibition about her using laser etching on straw mats. These etchings are not only meant to be reflected in images but also in the memories of all nations that need to embrace and not alienate themselves and their others.

As he is honored for his work in Kathmandu, Nepal, and Ahmedabad, India, in the months since his imprisonment, what needs to be demanded is for him to be cleared of wrongdoing and his safe return to the throng—the ebb and flow of the streets—the location of power from which he reports, inspires, and will always be remembered.

As bullets whiz by, as shrapnel shard, as hate pours from above

As blue skies curse, the wounded I nurse, as spite replaces love

It is home I long, as I boundaries cross, a shelter that I seek

A world for us all, white brown short tall, the boisterous and the meek

—Shahidul Alam, excerpt from “Place” (2017)

The exhibition Shahidul Alam: Truth to Power was on view at the Rubin Museum from November 8, 2019, to May 4, 2020.

Rahaab Allana is curator/publisher of the Alkazi Foundation for the Arts in New Delhi, a fellow of the Royal Asiatic Society in London, and an honorary research fellow at the University College, London. After completing his master’s degree from SOAS in London, he was a curator at the National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi. He has curated, edited, and contributed to many national and international exhibitions and publications.

Rubin Museum

150 W. 17th St., NYC

Get the latest news and stories from the Rubin, plus occasional information on how to support our work.