We have all experienced anger from a very early age. In Buddhism, anger is one of the five afflictive emotions, or kleshas, that can cloud our understanding of the world, along with pride, envy, attachment, and ignorance. But if we pay attention to the emotion, can it transform to give us a sense of clarity, to help us see what is important?

ERIC RIPERT:

I was a young chef in a kitchen, and I had a big kitchen to manage with a lot of young people around me as well who were not necessarily experts at what they were doing and they were making mistakes. I felt the responsibility of the kitchen, and the restaurant, and so on. And I would get so frustrated that it would end up becoming pure anger.

RAVEENA AURORA:

Chef Eric Ripert is an author, restaurateur, TV personality, and founder of Le Bernardin in NYC.

ERIC RIPERT:

I had tantrums, and I would throw plates on the floor, for instance, because I could not control that feeling that was coming from here, from the heart. It comes from here, and then it’s processed by the brain, and then it’s basically developing in your entire body, and suddenly, like, you explode.

RAVEENA AURORA:

Welcome to AWAKEN, a podcast from the Rubin Museum of Art that uses art to explore the dynamic path to enlightenment and what it means to “wake up.” I’m singer and songwriter Raveena Aurora and I have been learning about the transformative power of art throughout my life.

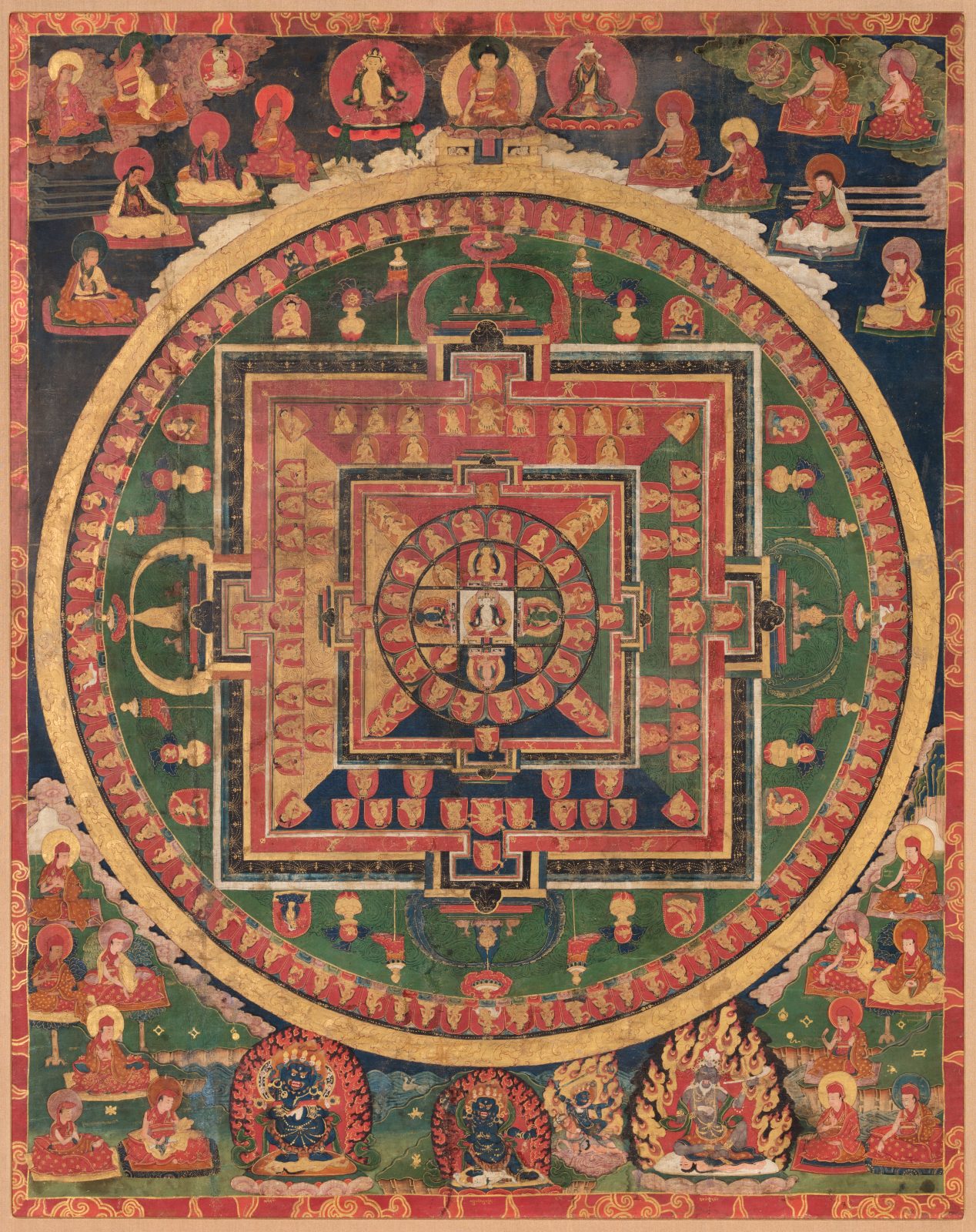

Since time immemorial, art has been used as a portal to better understand ourselves and the world around us. At the Rubin, a museum dedicated to art from the Himalayas, we believe art can inspire us on a path to awakening. And in this series, we’re using a specific artwork, the mandala, to explore this journey and the emotions that accompany us on the way.

But what is a mandala? A mandala is a guide. People from many cultures and religious traditions around the world use mandalas as maps to navigate their inner lives, including their emotions. Throughout this series, with the guidance of scientists, Buddhist teachers, writers, artists, and activists, we wrestle with five challenging emotions””anger, pride, attachment, envy, and ignorance””to help us take a new perspective on how emotions can influence our day-to-day experiences”¦and what they might be able to teach us if we get curious.

In this episode: anger.

Psychologist Tracy Dennis-Tiwary is a professor of psychology and neuroscience at Hunter College. She has been studying the science of emotions for nearly two decades and her most recent book looks at how challenging emotions can be good for you.

TRACY DENNIS-TIWARY:

Anger is the appraisal that our goal is blocked and the action readiness to overcome the obstacle.

RAVEENA AURORA:

Mark Epstein is a Buddhist and bestselling author, most recently of The Zen of Therapy: Uncovering a Hidden Kindness in Life. He is also a Freudian psychiatrist.

MARK EPSTEIN:

In an infant, in a young child, desire and anger, everything is all bound up as one.

TRACY DENNIS-TIWARY:

You know anger is very clear, you have a positive goal blocked, you know sadness is that you have the loss of a positive thing that you want. It’s all about this goal state, right, this thing you want.

RAVEENA AURORA:

Buddhist teacher, author, and co-founder of the Insight Meditation Society, Sharon Salzberg.

SHARON SALZBERG:

The first image that comes up for me is from the Buddhist psychology, where they liken anger””and again, it’s not a question of feeling anger, it’s a question of being lost in anger””but they liken it to a forest fire, which burns up its own support, which means it can damage or kill the host. And like a forest fire, it can burn really wild, so it might leave us in a place very far from where we want to be.

RAVEENA AURORA:

Dzogchen Ponlop Rinpoche is a leading Buddhist teacher and one of the foremost scholars and meditation masters in the Nyingma and Kagyu schools of Tibetan Buddhism.

DZOGCHEN PONLOP RINPOCHE:

We feel unhappy, and we feel this sense of””a little bit sense of disgust towards something or someone. And we feel that””sometimes we also feel that we want to do something, and that kind of ends up in harmful actions towards someone or to ourselves.

ERIC RIPERT:

When you are angry, you hurt yourself, and you hurt the other person as well. And by hurting the other person, you even hurt yourself more.

MARK EPSTEIN:

So, people either get””they get taken over by it, which, you know, usually””and then you end up acting out, you know, sort of mindlessly and destructively. You get taken over, but you indulge it, or you repress it. Those are the two tendencies that most of us have.

ERIC RIPERT:

It’s this explosion of, like, great energy. You feel very powerful. However, you’re powerful, but you are blind. You cannot control that energy, and that energy controls you. And until you realize that, you let anger come up. It’s a pattern. It comes from here, at least for me, from the heart, and it goes up, and then it can develop or not.

RAVEENA AURORA:

Ten year old Nora Wood is the daughter of AWAKEN’s executive producer.

NORA WOOD:

When I feel angry, I want to throw things, or want to tell””shout at somebody, the person that I’m angry at. Kind of feel like a boiling pot full of water, and like if you keep the top on too long, the water will overflow.

DZOGCHEN PONLOP RINPOCHE:

Like physically, you sometimes feel like hot, or shaking. You know you can feel the anger running through your core of your body as well.

TRACY DENNIS-TIWARY:

Our heart’s pumping, blood is getting to our muscles, our attention narrows and focuses. All of these things happen in our body to prepare us to act based on what we’ve appraised the situation to be. And the feeling part of emotions that we all know are sort of the outcome of all of those processes.

ERIC RIPERT:

When you are very angry, you have no idea that you are out of control. And then, whatever seems to be rational at the time, when you come down from that high energy coming from that negative emotion, suddenly, you realize that it was obviously not right, and you were sidetracked, and it was a mistake.

TRACY DENNIS-TIWARY:

You may not be fully, fully aware of what you’re thinking, but it’s definitely your mind snapping into action. You’re paying attention, your mind’s trying to make sense of what’s happening. Everything is happening on the order of milliseconds. So it may seem like your body’s responding before your mind, but it’s really happening in tandem.

And what’s also happening is the feeling that you’re having is in part just you know how strong, how aroused you are in that situation, how strong your reaction is in the moment. The great power of emotions is that they happen so quickly. They happen so automatically that it doesn’t take much energy for us to be immediately ready to respond.

RAVEENA AURORA:

Anger is one of those emotions that really feels like it just flares up, like a lightning bolt. The storm is brewing but the anger, the explosion, is quick and vast and has the potential for a lot of destruction.

ERIC RIPERT:

It’s a frustration that grows, that you cannot control. And that ultimately, at the end, you have this crazy energy that is almost like a volcano, it’s like an eruption of frustration. And then, you’re angry.

RAVEENA AURORA:

One of the things I find most interesting about it is that it doesn’t only happen in the context of say bigger things, like social injustice, but really smaller, inconsequential things as well. Like parking. In a way, that can be a good thing because it offers a lot of opportunities to work with this emotion.

MARK EPSTEIN:

I think just picking the ordinary times. You know, driving, finding a parking space. Like you’re driving around in the city, and it’s hard to find a parking space, and then you find one, and then somebody swoops in behind you and takes it, tries to take it from you.

And my first impulse is, you know, is to fight, and I remember one time where I got out of the car and said, you know, “Why don’t we flip a coin?” And the other person wasn’t a complete jerk and, you know, and agreed. So in that space where the anger could have come and dominated, I was able, just by pausing and thinking, not just watching the anger but actually, “Oh, like here’s a circumstance, like what could I do here?” Like I solved it momentarily a different way. You know. So I think that’s the challenge.

RAVEENA AURORA:

The other challenge is that we are working with an emotion that is so pervasive to our nature. If you think of anger as Tracy defines it, the emotional consequence of a block from something that we want, then we know that we’ve experienced anger from a very early age. This road is well traveled.

NORA WOOD:

Yesterday, my mom, we were playing””it was like nine, and my mom wanted to get me to bed, and I wanted to play soccer outside. And so when she came, I threw the ball into the garden. And then she shouted at me, and she was like, “That’s it! You’re not getting a ball for a week!” I didn’t think I had done anything wrong.

RAVEENA AURORA:

And then the next day”¦

NORA WOOD:

My mom said, “I’m really sorry that I got angry at you last night.” That felt good. I got my ball back, by the way. Any listeners that are nervous””don’t worry, I have my ball. [laughs]

DZOGCHEN PONLOP RINPOCHE:

As we can see clearly, that when we are so afflicted by anger, and when we are so overpowered by anger, we say things and we do things to other people, and that one action, like maybe one email [laughs], destroys all of you know the good things you have done to that person. You know that person you know does not remember all the good things you’ve done, but they only remember one thing””that is your email, the angry email, so to speak. So we can see also in action in our life that how anger destroys everything, every positive thing you have built in the past. With one moment of anger, you can destroy all of those things.

ERIC RIPERT:

I remember sitting down in my living room, and I’m talking about a long time ago, I’m 26 years old. And I’m coming back home after work, and day after day, I have this anger in me, and I’m coming home, I’m miserable. And the more I’m miserable, the more the team around me or the people interacting with me are, and then they’re leaving.

And it’s a big problem, and I don’t find the solution. I’m thinking, I’m like, “What’s happening in my life?” And I really had to um, I wouldn’t call it a meditation because at the time, I didn’t meditate, but I really had to search and try to find what was the problem. Why was I so miserable? And then, I realized that anger was the main problem of being so unhappy. Yes. And I made the commitment not to have those tantrums in the kitchen any longer, especially in the kitchen and with the staff, the team in the dining room, the way I was talking to people surrounding me.

MARK EPSTEIN:

We have this strange capacity as human beings to both be in the midst of our experience but also a little bit to the side of our experience. You know. We can be thinking, but also know that we’re thinking. We can be angry but also know that we’re angry.

ERIC RIPERT:

So in between realizing that anger is obviously a challenge, and it’s negative, and deciding to fight anger, and then sharing with the team. It takes time. It was a work in progress. And also, I trained people how to be angry chefs.

Because you feel powerful. You don’t know you have that weakness. You think you’re doing the right thing, you’re controlling a kitchen pretty well. So then, when I came back after work, I started to tell them that I didn’t want any violence in the kitchen again, non-physical violence. And it took a long time for some of my employees to make the switch, to change because they didn’t believe me. They were like, “That’s not possible. You cannot go to bed, and then you come back the day after, and you’re telling us that everything we have done for few weeks, few months was wrong, and you had this kind of, like, moment in your house, and now you want us to talk to the cooks and direct the restaurant in a totally different way.”

RAVEENA AURORA:

There are these moments where we have had enough of how we might be acting or reacting in the world, and we need to make a change. We all know what it feels like to reach our limit, to believe that how we have been doing things isn’t how we want to continue to do things. When it comes to anger, the interesting thing is that there’s a lot of energy that emotion generates and while it can be harmful, harnessed well, it can also be very effective. Sharon Salzberg.

SHARON SALZBERG:

There’s energy in the anger. We’re not passive. We’re not complacent. We are often more forthright. Like sometimes I think or talk about like being in a meeting, and it’s the angriest person in the room that’s insisting everybody look at that troublesome thing that no one wants to look at. You know. And we’re all studiously avoiding looking at it, but they’re insisting, “Look at that.” You know. So it’s got a certain like penetrating quality.

RAVEENA AURORA:

So anger can really shine a light on what is important. And in Buddhism, when one’s anger is acknowledged and transformed, what is gained is something called mirror-like wisdom.

DZOGCHEN PONLOP RINPOCHE:

If you really look at anger itself, the experience of anger, there’s so much quality of being vivid and bright quality of mind, right? It is a very powerful, powerful experience of mind. It is so bright”¦It’s like a deer in headlights, you know? It is so bright that everything feels like blank, that you can’t see it. And so, anger has that kind of inner experience that when you have such a strong anger, there’s so much clarity, so much brightness, that it kind of blinds us, and then we lose all kind of logic or reason, and we and we can also experience that physically.

SHARON SALZBERG:

You know when we have a strong feeling going on, usually we’re fascinated by the object, the story, the situation. And so it’s like if you have a really, really strong desire for a new car, for example, you spend your time thinking, you know, “Do I want that kind of upholstery or that kind of upholstery? Or this color or that color? Or what about music? How am I going to play music?” It’s so rare to kind of turn our attention around as though to ask ourselves, “What does it feel like to want something so badly?” But that’s what we do in meditation. It’s not so much what we’re going to do about the anger, or what the resolution needs to be, or why in the world you know we feel the way we feel. It’s like, “What is this? What is anger, actually?” And so we make that pivot. And then we try to let go of the add-ons,

DZOGCHEN PONLOP RINPOCHE:

If you have an experience of looking inward to this experience of anger, or the sensation or the feeling of anger, rather than verbalizing that anger in words, concepts, or you know justification””your justifying mind””then there’s a possibility for us to see the experience of anger as it arises in our body and in our mind. If we can connect with that experience, that raw energy of the anger, if we can connect with that, internally, directly, without being interrupted by thoughts, without being interrupted by outer objects, then that sharp edge of anger is turned inward and that can cut our normal or neurotic habits of anger, and then you can see a certain element of liberation or freedom, you know or transformation. [laughs]

TRACY DENNIS-TIWARY:

When you can channel that anger into perhaps more righteous indignation, you know or you know working for justice or some outcome that requires a lot of fight and a lot of energy, we couldn’t do it without anger and frustration and some of those unpleasant and what we find often distasteful emotions.

SHARON SALZBERG:

But the challenge seems to be not to be lost in it, but to capture that energy, to capture the positives””you know the insistence on speaking the truth, or being clear, the penetrating quality, and certainly the energy””without burning up ourselves.

ERIC RIPERT:

Today, of course, I have many tools to counteract anger, and at the time, I didn’t have that.

I start to have those feelings, and right away, I start to remind myself that first of all, it’s not important, and in ten years from now, I won’t even remember.

SHARON SALZBERG:

So if I, for example, can look at anger and be kind to myself even though I hate feeling it, not to let that shame or hatred take over, and be curious about it, then I see many things. You know. I do see the helplessness that’s embedded in the anger. I do see that it’s a changing state, even though it is very strong when it comes up. I do see that if I’m lost in anger, that I lose perspective. You know. I forget so much when I’m angry.

If I’m really, really, really angry at myself, for example, I forget the five nice things I did the same morning I did that stupid thing, you know? And so we just learn about the nature of all these feelings and about reality, if we can pay attention.

ERIC RIPERT:

Anger, as you know, has the power to basically, like, make your muscles very tight, and your body’s, like, all in pain. But when you start to smile suddenly, the dynamic change, right? [Laugh] When you’re smiling, or if you smile at someone, you really already like create something in that person.

Like, it’s very rare that if you smile at someone, they get frustrated with your smile. Usually, they smile back, or at least, they become neutral in their attitude.

DZOGCHEN PONLOP RINPOCHE:

But to do this, you know, there’s some need of, you know, mindfulness and awareness practice, to begin with. You know? So we need to have some familiarity of turning our mind inward.

RAVEENA AURORA:

Mindfulness is the ability to observe our emotions without becoming fully immersed in them but just looking. It’s when we get lost in the emotion that things get a little messy.

MARK EPSTEIN:

There’s an expression in poker when someone goes on a losing streak and they get frustrated and they start fighting to win back all of their losses. It’s called “going on tilt.” So the other sophisticated poker players know when somebody goes on tilt, because their anger is taking over, and they stop being careful, so they start you know betting more and losing more, and the other smart players take advantage of it.

So it’s like””you know it’s similar to the road rage thing. Like when you feel yourself going there, how do you””can you intervene with your mind to stop yourself from acting out the anger? You know? That’s a big challenge for a lot of people.

TRACY DENNIS-TIWARY:

I think the way to rescue ourselves from emotional distress, from mental health problems is to rescue these difficult emotions like anxiety, like anger, like fear, and not to just accept them as they can just be whatever they’re going to be but to realize that they’re not harmful. What’s harmful is the way we cope with them.

RAVEENA AURORA:

And what Tracy means by cope isn’t just about how we manage the emotion in the moment but, maybe more importantly, what we tell ourselves about ourselves when we’re feeling the way we do. Because what tends to happen when we get angry is that we feel”¦

SHARON SALZBERG:

A SENSE OF ISOLATION:

“I’m the only one who has ever felt this.” Or the sense of permanence. “This will never, ever change. This is what I’m going to feel for the rest of my life.” Or, sense of shame. “I’m so horrible a person. I shouldn’t feel this, or I should have been able to control everything. Why, you know. Why is this here?” Whatever it might be. And just really come to like, “What is this? What is anger?” And we try to feel it in our body, so that we have that deeper familiarity with it. And we kind of watch the anger movie. It’s like you watch the shifting moods.

[gong sounds]

RAVEENA AURORA:

At the Mandala Lab inside the Rubin Museum, the emotion of anger is presented in a very tangible way.

[gong sounds]

Hanging above a 20-foot long tank of water is a sight both serene yet full of deafening potential””eight glowing bronze, brass, and silver gongs.

TRACY DENNIS-TIWARY:

I love the gongs and where it’s very literally and experientially a transformation of energy but in the form of sound.

[gongs sound]

And even the way that the Mandala Lab takes us through that practice of you make the sound, you submerge it in water.

[gong sounds angrily, and then is dipped in the water to produce a surprising bend in pitch]

You see the ripples, it’s multisensory.

[quickly, a different gong sounds, and then is dipped in the water to produce a bend in pitch]

RAVEENA AURORA:

The anger might still be there, but our relationship to it, our resonance with it, can change. We can transform anger when we engage with it in a different way.

TRACY DENNIS-TIWARY:

So, also helping us sort of tune into the fact that emotions are multimodal in this way.

RAVEENA AURORA:

Have you ever slammed your anger into a pillow with a forceful punch? Give it a try. There’s a similar power in banging the gong but ultimately the real power comes through with the sense of relief as the water receives and transforms it into a calmer, clearer perspective. Eric came to better understand that transformation for himself.

ERIC RIPERT:

What makes me feel powerful today is when I do good things, when I have a positive impact on people around me. That makes me powerful. And if I do the contrary, if I get frustrated, or I’m self-centered, or selfish, or something like that, I feel weak.

I do not feel powerful. But it took me many, many years to arrive at this way of thinking. It’s not like suddenly, you wake up, and you are doing the opposite of what you thought was powerful, and you feel strong.

RAVEENA AURORA:

When we really look closely at anger, we realize that the feeling isn’t based in the fire and power that it initially seems to be but comes from a place that is seeking empathy and care, gentleness and, ultimately, love.

TRACY DENNIS-TIWARY:

It’s these difficult emotions like anxiety, sadness, anger, they’re a feature of being human. They’re not a bug. They’re not a malfunction. They’re not a failure of some you know standard of toxic positivity. You know what I mean? That if you’re not perfectly happy all the time, if you feel some anxiety, if you feel some anger, it’s a failure and you just have to fix it and eradicate it and prevent it. And the reason that sort of disease model of our emotions, of our like normal human emotions, is wrong but also potentially harmful is that if you want to rev up negative emotions, spiral them out of control; if you want to lose opportunities to learn to manage them and master them, then you should avoid all emotions. Like you should treat them like you’re broken, you should treat them like a failure, you should avoid them and fear them.

And so, this way that we talk about negative emotions is actually so counterproductive in that way that I think that these conversations we’re having about emotion, where we open up the possibilities, start to consider how negative emotions shouldn’t just be feared and reviled, I think these are really crucial and valuable conversations. And actually, if we can have those conversations, I think we’ll actually start making some real improvements in our collective mental health.

MARK EPSTEIN:

So I think kindness, especially thinking about society and how can all this impact the world that we live in actually””like just kindness, you know? Most people in our culture think that their hatred is greater than their love. They don’t really trust that the loving thing is strong, you know? So, to start to see how accessible kindness actually is, you know? Like what you were saying about the chef, realizing that his way of being with all the people working for him was making him unhappy and that there was another way, that’s such a great allegory for the greater society.

I like Thich Nhat Hanh’s thing about anger, which is, “Learn to hold anger like a baby.” Hold anger the way you would hold a baby. You wouldn’t beat up on the baby for her desire. You know you hold it lightly. You hold it lightly. Carefully, though.

RAVEENA AURORA:

Thank you for listening to Season 2 of AWAKEN, a podcast from the Rubin Museum that explores the dynamic path to enlightenment and what it means to “wake up.” I’m singer and songwriter Raveena Aurora.

You just heard chef Eric Ripert, psychotherapist and author Mark Epstein, Buddhist teacher and scholar Dzogchen Ponlop Rinpoche, psychologist and neuroscientist Tracy Dennis Tiwary, author and Buddhist teacher Sharon Salzberg, and ten-year-old Nora Wood.

AWAKEN is produced by the Rubin Museum of Art in collaboration with SOUND MADE PUBLIC.

Music produced by Alexis Cuadrado and Hannis Brown with additional tracks from Blue Dot sessions.

You can continue the conversation by following us on Instagram at @rubinmuseum. And if you’re enjoying this podcast, leave us a review wherever you listen to podcasts, and tell your friends about the conversation you just heard.

This is episode 5 of a 7 part series inspired by the Mandala Lab at the Rubin Museum””an immersive space for social, emotional, and ethical learning. Come explore the Lab in New York City, or in one of the installations that is traveling the world. Visit rubinmuseum.org to learn more about the Museum and about the art, cultures, and ideas of Himalayan regions. We look forward to seeing you.

AWAKEN Season 2 is hosted by singer and songwriter Raveena Aurora. Guests featured in this episode include psychologist and neuroscientist Tracy Dennis-Tiwary, Buddhist teacher and psychotherapist Mark Epstein, Buddhist teacher and scholar Dzogchen Ponlop Rinpoche, renowned chef Eric Ripert, Buddhist teacher and author Sharon Salzberg, and student Nora Wood. Read more about these guests below.

View the Vairochana Mandala which inspired this season of AWAKEN and the Rubin’s Mandala Lab below.

Sarvavid Vairochana Mandala; Tibet; 17th century; Pigments on cloth; Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art, Gift of Shelley and Donald Rubin; C2006.66.346

For Raveena, music is meant to be a “complete expression of the self.” It’s a truth she’s leaned on through a whirlwind couple of years, which saw a potent flurry of output and a pointed ascent into the conversation with her critically acclaimed 2019 debut full-length, Lucid, and 2020 follow-up, Moonstone EP. Asha’s Awakening takes listeners on an epic deep dive into Indian culture. An homage to her heritage as a first-generation descendant of genocide survivors and Reiki healers, the album incorporates influences from Bollywood and celebrated Indian artists like R.D. Burman and Asha Bhosle, as well as Western music—specifically R&B, rock, and soul—and melds the genres prevalent throughout Raveena’s catalog into one cohesive body of work. The album also marries eras in time, fusing together a contemporary take on sounds influenced by Alice Coltrane and Asha Puthli from the 60s and 70s with those of Timbaland, Missy Elliott, M.I.A., and Jai Paul from the early 2000s. It is a labor of love that represents her evolution as an artist. Raveena remarks, “I think it’s really fun putting people in uncomfortable positions to receive new sides of you. The human experience is so vast.”

Inspired by artists like Sade, Corinne Bailey Rae, Minnie Riperton, and Indian singer Asha Puthli, Raveena is a highly creative, dynamic, and spiritual artist who aims to build fully realized worlds within each of her projects: conceptual experimentations in sound, threaded together by stories of healing and self-realization meant to be experienced from start to finish.

Tracy A. Dennis-Tiwary, PhD, is a professor of psychology and neuroscience at The City University of New York. As director of the Emotion Regulation Lab, she conducts NIH-funded research on anxiety, suicide, and digital therapeutics for stress and anxiety. She is the cofounder of Arcade Therapeutics, which translates cutting-edge science into digital tools for behavioral health, and co-executive director of the Center for Health Technology at Hunter College. She is the author of Future Tense: Making Anxiety Our Superpower.

A highly-regarded psychiatrist in private practice in New York City, Mark Epstein, MD, is the author of a number of books about the interface of Buddhism and psychotherapy, including Thoughts without a Thinker, Going to Pieces without Falling Apart, Going on Being, Open to Desire and Psychotherapy without the Self. The Trauma of Everyday Life uses the Buddha’s biography as a means of exploring the hidden psychodynamics, and contemporary relevance, of Buddhist thought. He received his undergraduate and medical degrees from Harvard University and is currently a clinical assistant professor in the postdoctoral program in psychotherapy and psychoanalysis at New York University.

Dzogchen Ponlop Rinpoche is a widely celebrated Buddhist teacher and the author of Emotional Rescue, Rebel Buddha, and other books. A lover of music, art and urban culture, Rinpoche is a poet, photographer, accomplished calligrapher and visual artist, as well as a prolific author. Rinpoche is the founder, president, and spiritual director of Nalandabodhi, an international community of Buddhist centers. Rinpoche is acknowledged as one of the foremost scholars and meditation masters of his generation in the Nyingma and Kagyu schools of Tibetan Buddhism. He is known for his sharp intellect, humor, and easygoing teaching style, for launching the kindness initiative #GoKind and for his outreach to communities internationally.

Eric Ripert is the chef and co-owner of the acclaimed New York restaurant Le Bernardin. Born in Antibes, France, Ripert moved to Andorra, a small country just over the Spanish border as a young child. His family instilled their own passion for food in the young Ripert, and at the age of 15 he left home to attend culinary school in Perpignan. At 17, he moved to Paris and cooked at the legendary La Tour D’Argent before taking a position at the Michelin three-starred Jamin. After fulfilling his military service, Ripert returned to Jamin under Joel Robuchon to serve as chef poissonier. In 1989, Ripert seized the opportunity to work under Jean-Louis Palladin as sous-chef at Jean Louis at the Watergate Hotel in Washington, D.C. Ripert moved to New York in 1991, working briefly as David Bouley’s sous-chef before Maguy and Gilbert Le Coze recruited him as chef for Le Bernardin. Ripert has since firmly established himself as one of New York’s “and the world’s” great chefs. In September 2014, Ripert and Le Coze opened Aldo Sohm Wine Bar, named for their acclaimed wine director Aldo Sohm. That same month, the two expanded Le Bernardin’s private dining offerings with Le Bernardin Privé, a dynamic space above Aldo Sohm Wine Bar that can accommodate a range of events. Ripert is the Vice Chairman of the board of City Harvest, working to bring together New York’s top chefs and restaurateurs to raise funds and increase the quality and quantity of food donations to New York’s neediest. When not in the kitchen, Ripert enjoys good scotch and peace and quiet.

Sharon Salzberg, Cofounder of the Insight Meditation Society in Barre, Massachusetts, has guided meditation retreats worldwide since 1974. Her latest books are Real Life: The Journey from Isolation to Openness and Freedom and Finding Your Way: Meditations, Thoughts, and Wisdom for Living an Authentic Life. She is a weekly columnist for On Being, a regular contributor to the Huffington Post, and the author of several other books, including the New York Times bestseller Real Happiness: The Power of Meditation, Real Change: Mindfulness to Heal Ourselves and the World, Faith: Trusting Your Own Deepest Experience, and Lovingkindness: The Revolutionary Art of Happiness. Ms. Salzberg has been a regular participant in the Rubin’s many on-stage conversations and regards the Rubin as a supplemental office.

Nora is a ten-year-old student and the daughter of the producer of AWAKEN.

Get the latest news and stories from the Rubin, plus occasional information on how to support our work.