Walking in the footsteps of the past, researcher Matthew Akester took an unconventional journey to explore Tibetan culture and history. His travels were long, but the real dedication came later, when he researched and re-translated the earliest and best-known guide to Tibet. Originally written in the 19th century by the greatest modern master of Tibetan Buddhism, Jamyang Khyentsé Wangpo, the guidebook has fueled scholarly interest through the 20th century to today. Akester thought it was time for an update. We spoke with Akester to discuss his process.

Matthew Akester: About 10 years. Actually for longer than that I was “traveling across nine passes and through nine valleys,” as the Tibetan proverb says, exploring the country with the help of Khyentsé’s guide, walking with a backpack full of camping gear, and taking rides on trucks and buses, horses and donkey carts. But most of the actual work was reading—that is, the work of recovering the rare, local literary sources in which the history of local temples is often preserved, as well as surveying a vast range of published traditional literature for any mention of the places.

Of course, interviewing local people, monks and scholars, was educative, but I often found that their knowledge of a place’s history was a partly remembered version of one of these texts. The largest single group of rare guidebook manuscripts I was able to find had recently been reproduced in book form by the Tibetan Library in Dharamshala, India. And I was able to pass on several other rare books to Gene Smith and the Tibetan Buddhist Resource Center (formerly based in New York) to be digitized and preserved. The photo research was also painstaking, but greatly facilitated by access to the photographs taken by the late queen mother of Sikkim on her 1935 to 1936 pilgrimage, some of which are published for the first time in the book.

Then I wanted hand-drawn maps, and it took a couple of years working with the very talented and patient graphic designer, Ken Okuma, to produce a series of them to accompany the text. His work is a highly valued contribution and was kindly sponsored by the Khyentse Foundation.

Basically, all the materials for the book had been assembled by 2006, and one way or another, it has taken a decade since then for it to finally appear in print. This was possible only due to the kindness of Dzongsar Jamyang Khyentsé Rinpoché’s foundation, and this seems a good opportunity to express my gratitude.

Khyentsé would have been brought up to regard central Tibet as a spiritual heartland blessed by the ancient temples and past masters of the tradition, but he found it rather a place of moral and spiritual degeneration. Centuries of civil war between Tibetan factions and their Mongol allies had produced by his time a theocratic oligarchy that had succumbed to Manchu imperial control and corporatized the clerical establishment. He found the remains of sacred traditions sunk in neglect. And this was a formative experience for him—he went on to become an encyclopedic scholar and master, the greatest of his day (1820–1892), who chiefly inspired an intellectual and religious revival in the kingdom of Dergé in Kham, often known as the Rimé movement, that has had such a profound influence on the teaching of Tibetan Buddhism as we know it today.

The guide itself seems to have been the first of its kind (it was probably composed in the 1850s)—we don’t have any earlier examples of guidebooks describing pilgrimage itineraries in central Tibet, or indeed any other region of Tibet. It is strikingly modern as a literary form, and I suggest in the book that it should be read as an expression of the Rimé philosophy.

So, of course, it has attracted the interest of foreign scholars. An English translation by Alphonsa Ferrari—a student of Giuseppe Tucci who had never visited Asia—was published in 1958. It was annotated by Luciano Petech, one of the scholar Giuseppe Tucci’s close disciples and who also had not visited Tibet, with the help of Hugh Richardson, the former British representative in Lhasa who had taken a scholarly interest in Tibetan history. This book became the standard reference work on the monuments and traditional geography of central Tibet in contemporary Tibetan studies—now a fast-growing academic field—and remains so. When I started my travels, I realized that with the ability to visit most of the places, and the significant quantity of historical literature that had now become available, it would be possible to do a major update. And that is what this book is.

The 1980s was an extraordinary period in Tibet. The generation of people educated before 1959 were released from the prisons and labor camps and began teaching the generation educated under Communism, many of whom were keen to study and revive traditional knowledge and culture. Monasteries and temples were rebuilt, monastic education reintroduced, Tibetan language taught in schools and colleges, classical works of Tibetan literature reproduced and modern works published.Tibetan culture was to some extent rekindled from the ashes of the Maoist period.

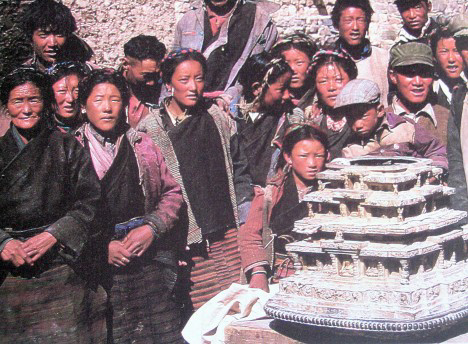

Local people return a silver model mandala hidden during the Cultural Revolution to Ralung Monastery. Photo: Stone Routes, 1985.

Unfortunately for me, I missed out on most of it. The liberalization ended with the popular independence protests that erupted in Lhasa in 1987 to 1989 when martial law was imposed—as it was all over China after the Tiananmen movement. As soon as independent travel in central Tibet became possible again, in 1992, I returned to begin research on the location and present condition of numerous places of historical interest.

By then, elementary restoration had been completed at many local monasteries and temples, as well as at the better-known ones, and was underway at many more. But this work was generally done with the meager resources of local communities, and although the government continued to tolerate religious activity, it certainly did not make it easy. At the same time, the landscape was being rapidly transformed under new policies favoring construction of infrastructure, immigration, and urbanization. Tibet was changing fast, and it seemed like an important moment to try and take stock of its remaining heritage.

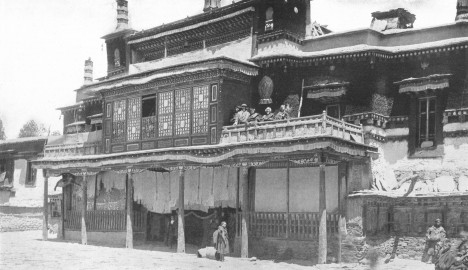

Lhalung Temple, 1906. Photo: John Claude White.

Lhalung Temple, 1993. Photo: Matthew Akester.

Get the latest news and stories from the Rubin, plus occasional information on how to support our work.