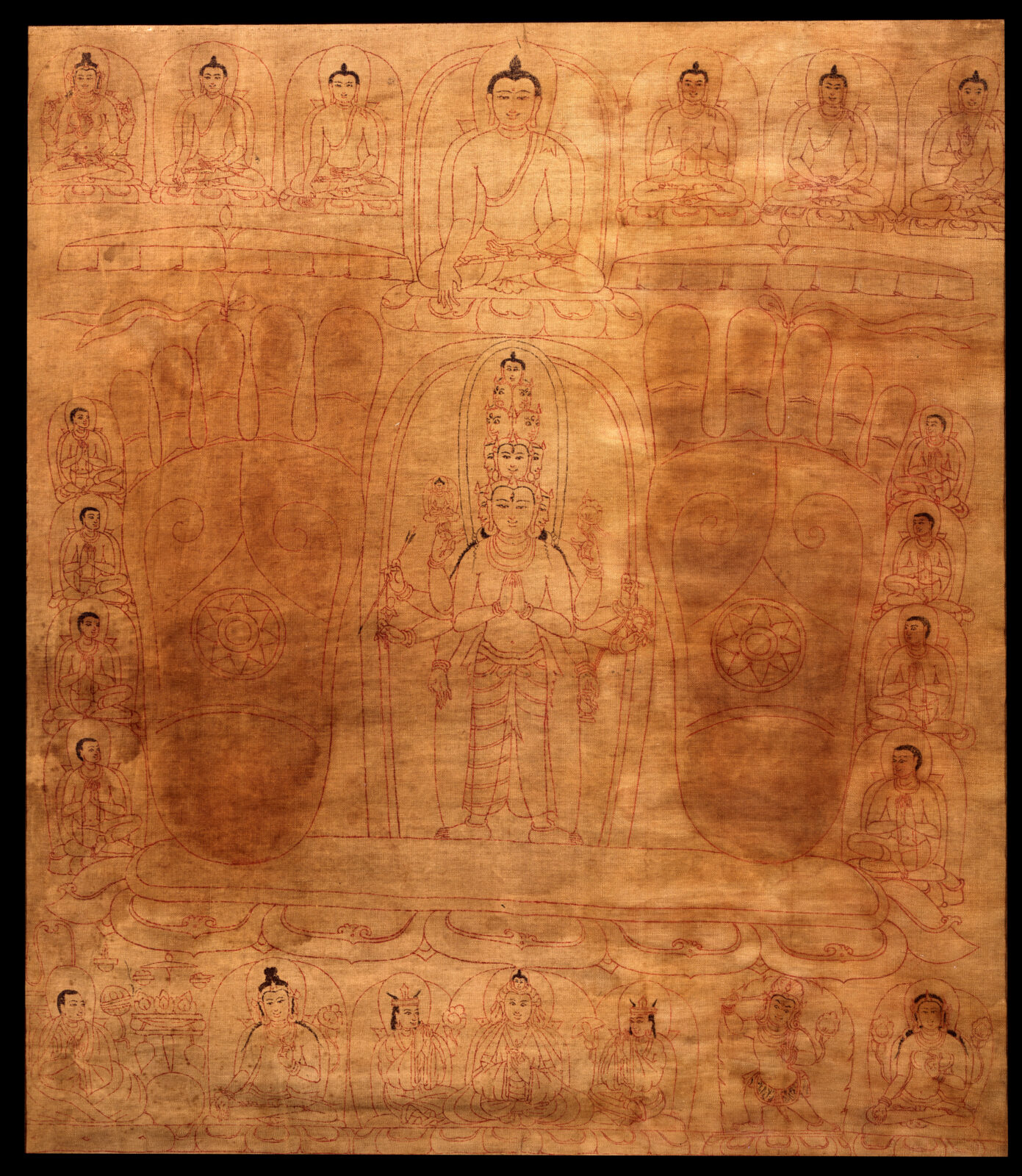

For the first 500 years after the Buddha’s death, his followers only depicted him in aniconic forms such as a horse with no rider, a set of handprints, or footprints. Though eventually his followers began to depict him in human form, the tradition of using handprints and footprints continued into Tibetan art. Below is an image of the bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara flanked by two footprints.

One of the most important concepts in Buddhism is the idea of nonself, but what exactly does this concept mean and how did it come about?

The above sculpture depicts the historical Buddha, who discovered that the self is a construct.

To understand what the Buddha was talking about when he brought up the concept of nonself, you have to brush up on your Sanskrit and early Upanishadic thought.

Traditionally, the type of Hindu philosophy based on the Upanishads teaches the doctrine of atman/brahman. Essentially, it teaches that every person is an eternal self (atman) that is part of the eternal essence (brahman) that pervades the universe; in order to achieve enlightenment, one must realize that the eternal self is the same as the external brahman. However, the Buddha denied this position and instead put forth the idea of anatman, which we translate to nonself. The idea behind nonself is that there is no singular thing that we can actually define as a self.

After the Buddha passed away, his ashes were divided into eight stupas, or reliquaries, that were used as the first Buddhist monuments. They represent the Buddha’s mind in an iconic form.

So if the self doesn’t exist, who is the person we see in the mirror, and who are all these other people that appear to be their own being? The Buddha said that what we perceive as an individual self is really just the five skandhas, or aggregates. They are form, feeling, perception, volition, and consciousness.

The first one, form, is very simple as it refers to the physical form of our bodies as well as all material phenomena. Of course, we are more than just our physical body, so the next aggregate the Buddha mentions is feeling. This feeling is different from emotions; rather, Buddhists believe this feeling consists of the three ways we react to all thoughts or stimuli: positive, negative, and neutral. Any type of experience we have, whether real or imagined, we have a positive reaction, a negative reaction, or are completely neutral toward it. These feelings reinforce habits, making us cling to the things and experiences we like while trying to avoid those we dislike.

The next aggregate is perception, or the mechanisms by which we recognize physical and mental objects. After perception comes volition, or the motivation to perform an action. The last aggregate is consciousness, which interprets and applies concepts to both mental and physical stimuli. Consciousness then misinterprets the other aggregates as being one unified entity moving forward through time.

The five skulls on top of the god of death Yama, depicted above, represent the five aggregates.

Buddhists believe that by understanding these physical and mental processes, we can unlearn the fundamental mistake that keeps us locked in suffering—the mistaken belief that the “I” exists. That’s why the notion of nonself is so important to the Buddhist tradition—it is the key to our awakening.