Crowned Buddha; Northeastern India; 10th century; Stone; Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art; C2013.14

Crowned Buddha; Northeastern India; 10th century; Stone; Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art; C2013.14

What is the relationship between religion and power? Since the Himalayan artworks in the Rubin Museum’s collection are deeply rooted in the religious traditions of Hinduism and Buddhism, they are the perfect starting point to investigating this complex relationship.

Religious power systems are deeply intertwined with the power systems of gender, political rule, scholarship, and nature. In Himalayan cultures, sacred objects, people, and places are believed to be imbued with capacities and abilities far beyond the world we ordinarily see, and the art at the Rubin reflects this.

We often question whether church and state should mix. Do the two complement each other or corrupt each other?

While religion and politics were not always seen as distinct in Asia, Buddhists debated whether true spiritual liberation was compatible with ruling a kingdom. The Buddha himself was raised to be a great king, but he renounced luxury and power to seek a solution to earthly suffering.

By contrast, a great emperor could use political power to spread the Buddhist message and convert the world. Emperor Ashoka (268–232 BCE) fought bloody wars to conquer India, then issued edicts expressing remorse for violence and encouraging religious tolerance and compassion among his subjects. Buddhists credit him with sending out missionaries and distributing the Buddha’s relics all over Asia.

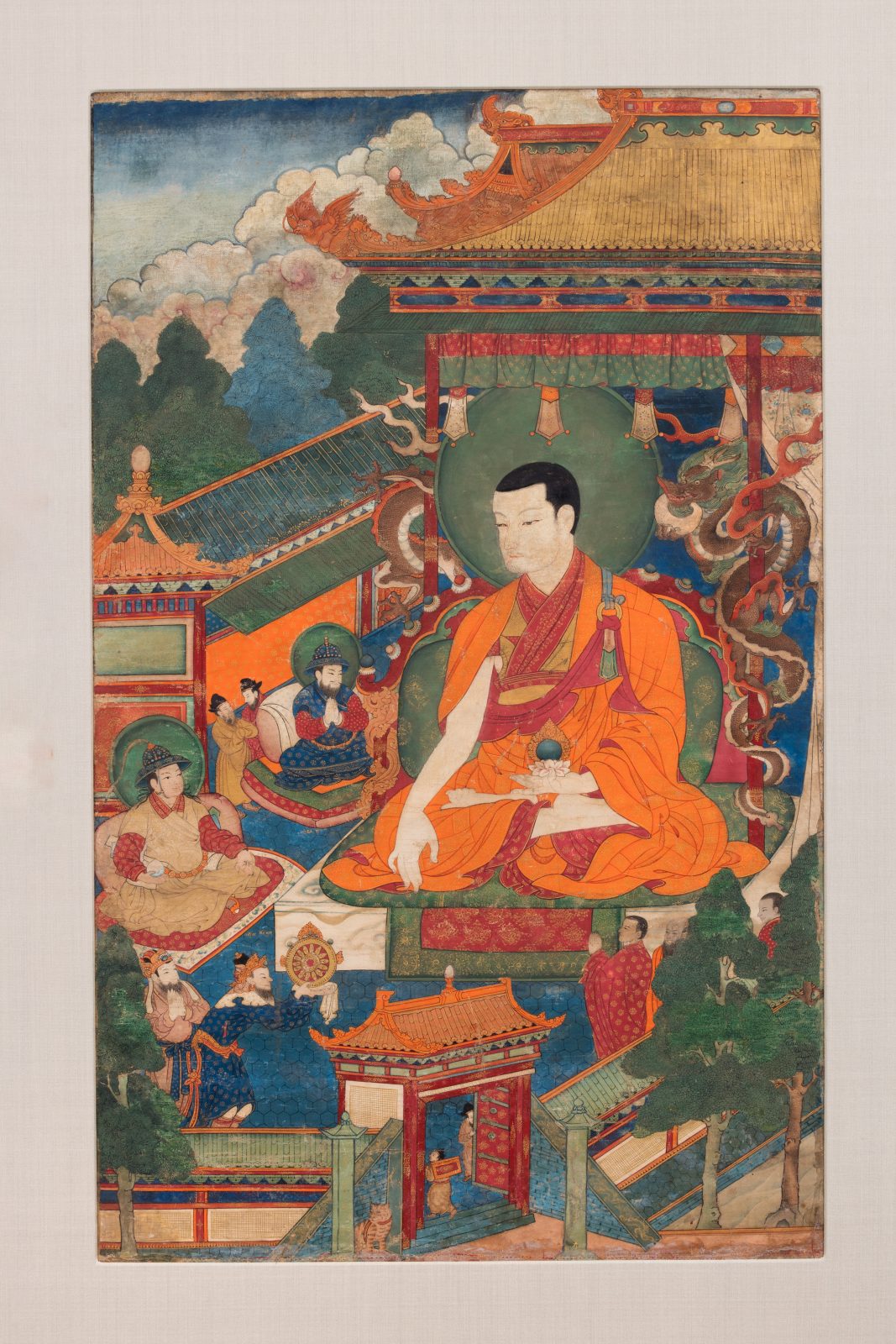

Chogyel Phakpa (1235–1280) initiating Qubilai Khan (1215–1294); Tibet; ca. 16th-17th century; Pigments on cloth; Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art; C2002.3.2

From the beginnings of the Tibetan Empire, Tibetan rule depended on spiritual power. In contrast to European monarchies, which invoked the divine right of kings, Tibetan rulers were believed to be enlightened or divine beings. According to legend, the first Tibetan rulers descended from gods who climbed from heaven on a sky-rope. The emperors Songsten Gampo, Trisong Detsen, and Relpachen are depicted as bodhisattvas who introduced Buddhism through images, monasteries, and holy texts.

Early rulers sought political control and enhanced personal power by controlling the secret rites of tantra. Foreign rulers also viewed Tibetan tantric masters as the keys to empire, especially after Chinggis (Genghis) Khan conquered Tibet. In exchange for their initiation into rituals that empowered them for global conquest, the Mongols allowed the hereditary Sakya masters to rule Tibet as their vassals after 1260. Later rulers of China and Mongolia sought out similar patron-priest relationships (choyon) with Tibetan rulers to solidify their rule, which encouraged Tibetan Buddhism to spread further.

The Potala Palace and the main Monuments of Lhasa; Tibet or Inner Mongolia; 18th - early 19th century (ca 1757-1804); Pigments on cloth; Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art; C2009.4

When the Fifth Dalai Lama came to power in 1642, he proclaimed a union of religion and politics (chosi sungdrel) in Tibet. The Dalai Lamas are the best-known example of a Tibetan reincarnating lineage, in which each Dalai Lama is believed to be the reincarnation of a previous one. As an embodiment of the compassionate bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara, the Dalai Lama was believed to choose the circumstances under which he would be reborn. A lot of intrigue resulted from new incarnations being children who were too young to rule.

Tibetan regents and Qing imperial governors often schemed to keep the Dalai Lamas off the throne. Four Dalai Lamas mysteriously died before the age of 20, and the Thirteenth Dalai Lama, the last one who had full power over Tibet in the early 20th century, took his throne after uncovering an attempt by the regent to kill him with black magic. The current Dalai Lama’s religious prestige made him a natural leader of Tibetans in exile after 1959, but he recently relinquished political power.

While the Buddha preached a renunciation of the world, his own life narrative intertwined the spiritual power of the dharma and political power. Buddhism could not have spread throughout Asia without the support of great emperors like Ashoka, and Buddhists consequently respected these rulers as deities. Tibetan Buddhism in particular depended on political power for its propagation, from the great dharma kings who founded Tibet to the Mongol and Chinese empires that bolstered their power through supernatural techniques and spiritual alliances. This close union of religion and politics in Tibet has not always been harmonious, as evidenced by sectarian conflicts and monastic intrigues, but it certainly has been a defining part of the region’s history.

William Dewey was formerly a curatorial fellow at the Rubin Museum. He completed a PhD in Tibetan Buddhism from the University of California, Santa Barbara, and spent a year teaching at the Rangjung Yeshe Institute in Kathmandu.

Get the latest news and stories from the Rubin, plus occasional information on how to support our work.