Mongolia

19th century

A skull cup is an attribute of tantric deities and is usually paired with a curved knife. It can symbolize a mind filled with the bliss of realizing the true nature of reality.

Mongolia

19th century

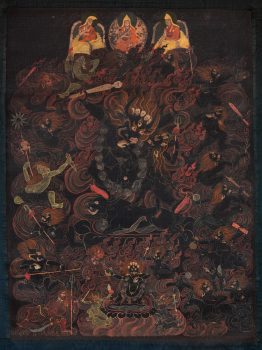

This painting depicts one of the primary protective deities of the Gelug tradition, which became popular in Mongolia after the Mongolian ruler Altan Khan (1507?–1582) invited a gifted Gelugpa monk to Mongolia in 1577. The monk, who taught and converted the khan, was given the Mongolian title Dalai Lama. As a protector (dharmapala), Yama is considered the defender of Gelug tradition in particular. The painting depicts him brandishing a skull club and a noose while standing on a buffalo. Below is another form of Yama who is armed with a chopper and a skull cup standing on a corpse. The top register depicts Tsongkapa, the founding teacher of the Gelug tradition and his two main disciples. The remaining figures are members of Yama’s retinue.

The end of this life marked by the cessation of bodily functions followed by decay. According to Buddhism, after death consciousness transitions to an intermediate state known as the bardo before embarking on another life.

Prescribed practices that carry symbolic meaning and value within a specific tradition and are intended to attain a desired outcome. Rituals are usually done as part of a ceremony or regular routine.

Protectors of Buddhist teachings who destroy obstacles that impede the path to enlightenment. The more frightening and gruesome their appearance, the greater their power.

Mongolians have been widely active in the Tibetan Buddhist world, playing a key role in Tibetan culture, politics, and relations with China. In the 13th century, the Mongol Empire—the largest contiguous empire in world history—facilitated the spread of Tibetan visual culture.

Get the latest news and stories from the Rubin, plus occasional information on how to support our work.