Lyla June Johnston:

My grandfather, my clan, always taught me eh, this is from the Dene language, and eh is just one syllable. But it contains so much grounding, information, and it’s the organizing principle of our community. And it means interdependence. It means being there for each other. It means knowing what your clans are, who your ancestors are, and how that makes you relate to other people, and where they’re descending from. Because we’re there for each other, we have enough and we take care of one another in a good way.

Devendra Banhart:

Indigenous musician, author, and community organizer of Navajo, Cheyenne, and European lineages Lyla June Johnston.

Lyla June Johnston:

And of course, that extends to Mother Earth, that we always offer her offerings. Every morning, noon, dusk, and night, we give her offerings to thank her for everything that she gives to us. And when we say our prayers, the first God that we mention is Mother Earth, and we honor her.

Devendra Banhart:

Welcome to season 5 of AWAKEN, a podcast from the Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art about the dynamic path to enlightenment and what it means to “wake up.”

I am Devendra Banhart, singer, songwriter, artist, and your host. In this season, we hear from experts in the realms of art, social science, Buddhism and more to better understand how interdependence is the foundation of every aspect of our lives.

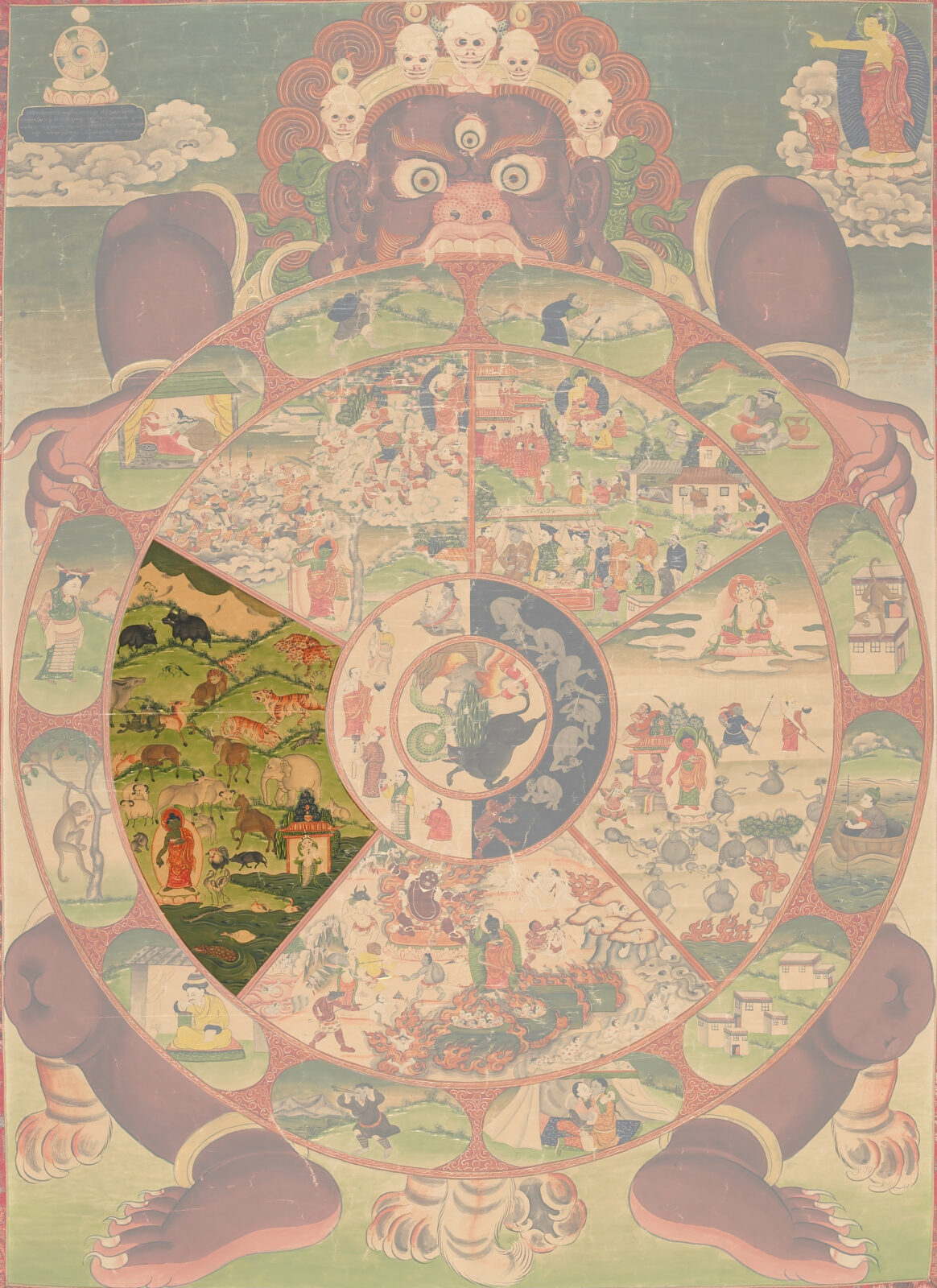

Himalayan art has long been a pathway to insights and awakening, and over the course of eight episodes we look specifically at a painting of the Wheel of Life to see what it can teach us about the interconnected nature of existence.

Throughout this journey, we’ll discover how greater awareness of our interdependence can be the wake up call that motivates us to take actions for a better world.

In this episode: Ecology.

One of the places we see interdependence at work most clearly is in the natural world.

Again, Lyla June.

Lyla June Johnston:

When systems are in balance, there’s a lot of interdependence. And the most obvious manifestation of that on earth is the relationship between mammals and plants. Mammals need oxygen, and plants need carbon dioxide. And when we inhale, we inhale oxygen, and we exhale carbon dioxide, and the plants are the reverse. So for a long, long time, the plants and the mammals have been exchanging breath, for a great part of earth’s life’s evolutionary history. A lot of people think that humanity is inherently warlike, and it’s always survival of the fittest and whoever’s strongest and bestest and fastest will always win. But if you really look at many, many, many facets of nature, it shows that it’s not a competition. That it absolutely is about a dance between elements, between organisms, between resources that we all need to live.

Nicholas Christakis:

When I was a young scientist, it would’ve been considered crazy to imagine that trees were communicating. But they are. And the ways in which they are is increasingly becoming known.

Devendra Banhart:

Professor Nicholas Christakis is a social scientist and physician who conducts research in the areas of social networks and biosocial science. He directs the Human Nature Lab at Yale University.

Nicholas Christakis:

And it’s not just that they might elaborate chemical substances into the soil like a tree that’s stressed might change the chemicals that its roots, elaborate and send signals in the soil to other trees nearby that, you know, I’m being felled by a logger, you know, I’m being killed. Or I am suffering a fungal infection. Uh, and here’s the chemicals that I’m releasing. There’s even some thinking that trees might, the roots might pulse in a way that creates sound waves underground so that the trees are like talking.

Now these are metaphors we’re using. The trees aren’t actually talking. But, it’s fascinating to imagine these, and there are many other examples of this.

Lyla June Johnston:

The manifestation of all these plants and animals is purposeful. And every rock has a purpose. Every deer has a purpose. Every star has a purpose, every species has a purpose, and every human has a purpose. Every person has a purpose. We’re all here on purpose by design to fulfill our certain responsibility within the ecosystem. And so, human beings are designed to be a keystone species. We are designed to uphold entire ecosystems. And so I know that interdependence is not only a thing within nature and, and, and completely integral to nature, but it’s also bigger than interdependence.

Nicholas Christakis:

The ecological world in which we live is also encoded in the pattern of our social connections. Social networks are a solution, not just to the immediate threats that a group may face, but they’re a solution to the evolutionary threats our species have faced. We form friendships to solve a problem. The reason we form friendships is precisely so as to survive. And therefore the capacity to form friendship was advantageous to us in the ancestral past. We could have been a primate species that didn’t form friendships that lived separately and came together once a year to mate. But it’s not the kind of species we are. And the reason is that it was adaptive for us to form these networks.

Devendra Banhart:

A network of people who are aware of our role in the greater whole, makes for a healthy environment.

Lyla June Johnston:

It’s about compassion and about learning what we’re meant to learn here on earth. And not only fulfilling our sacred obligation to other plants and animals, but supporting and facilitating their obligations. So, for example, the butterfly has its sacred purpose. Its sacred rule. And when we protect the milkweed and we plant the milkweed, we’re helping the butterfly do its job. And we’re helping the milkweed do its job, which is to help feed the birds and the butterflies. So everything has its place here. And our job is to support each thing to ring out its purpose the best that we can.

Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche:

The Buddha said three parallel universe: Universe in the mind, universe in the body and universe out there. And these three things are totally connected.

Devendra Banhart:

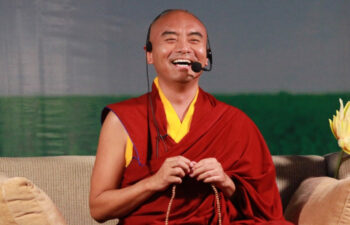

Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche is a renowned meditation teacher, author of several books on Buddhism, and head of the worldwide Tergar Meditation Community.

Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche:

So your mind, whatever there in your mind is there in your body, whatever there in your body is there in the earth. Stars, galaxies, entire universe, they’re all related. So therefore we influence like earth, we influence the earth, earth influence us. And if we keep good connection with the kind with the earth, we get also happy. We get more benefit.

Devendra Banhart:

When we come to truly understand and embrace our interconnectedness, our world expands. There are many ways to do this. Lyla June has created her own rituals around it.

Lyla June Johnston:

One of the small things I do to live in reciprocity with Mother Earth is I fill up my bird bath every chance that I get if I see it’s gone dry, because this is my small way of giving a little gift to the birds, a place to rest, a place to bathe, a place to drink. And I like to do this because it’s an act of service. I don’t get anything from it. It’s an act of giving to a species outside of my own. I also really like to compost. If you think about it, we take so much from the earth. We take so much from the nutrients of the soil to the raw metals, raw materials, the cotton, the polyester that we make our jackets out of is, comes from the oil of the earth. We have so much that we take, and yet we don’t give her our urine. We don’t give her our feces, which we used to. That was part of the cycle, was to give those nutrients back to the earth. We don’t even give her our body. When we die, we inject ourselves with chemicals and put ourselves in a box, and we don’t ever decompose our bodies. So we just spend our lives taking and never giving back any, uh, energy to the soil, to the animals, to the plants. And so composting is just the act of not throwing away food scraps that would just go into the landfill and in trapped in a plastic bag, but go back to the earth and actually those nutrients get redeposited into the earth.

Devendra Banhart:

For Buddhists around the globe, how we treat other sentient beings is paramount.

This season we’re focusing on a painting of the Wheel of Life in the Rubin Museum’s collection. The Wheel of Life, also known as the Wheel of Existence, is a foundational symbol in Buddhism and offers a visual representation and reminder of the cycle of life, death, and rebirth. Part of the wheel depicts the six realms of existence where it is possible to be reborn. To see the artwork in detail, go to rubinmuseum.org/wheel.

Here, Professor Annabella Pitkin who teaches Buddhism and East Asian religions at Lehigh University, talks us through the animal realm.

Annabella Pitkin:

It’s mostly green. We see hills and mountains. We see snow capped peaks, the snow capped peaks of Tibet and the Himalayan region, and a sky in the very upper register of the image. We see water that has fish and possibly a crocodile down at the bottom of the image. And we see green shores of the river or the ocean or the lake. And we see these lovely verdant hills on which animals are grazing and walking.

There’s a lot of love and care and knowledge of animals that’s visible in this lovely little vignette. And the animals are all spending time together in a quite a delightful way. But Buddhist philosophers and teachers explain that the animal realm, nevertheless, is one of considerable suffering. In fact, it’s considered a terrible form of rebirth, much, much more full of suffering than the human realm or the God realm, because animals are trapped, first of all, by human beings. Animals are often tortured and harmed, killed and eaten, made into slaves by human beings who are extremely cruel to them. And the early Buddhist writers, they had no illusions about the ways that human beings are capable of treating animals.

They described the ways that humans treat animals in very, very stark terms. And that is a major component of why this is a realm of suffering. It’s because its beings don’t recognize their interdependence with animals. And more broadly with the ecosystems in which we all live.

Devendra Banhart:

The imagery in the wheel of life is centuries old and yet, here we are, still doing the same thing, and at such a high cost.

Lyla June Johnston:

The culture who’s about profit maximization, that philosophy of the world will guide and drive and, and mediate their relationship to Mother Earth, which of course is about extraction, extracting as much as you can as quickly as you can to sell for profit at the highest price. If your value system is reciprocity, which some call it a spiritual thing, we just call it like what you’re supposed to do, it’s just the mature kind thing to do. Then your relationship to Mother Earth is gonna be mediated by this ethic of reciprocity, which is to give as much as you take and to find the joy in giving as much as you find the joy in receiving and to be an active member of a family.

We are part of a huge family that has many different species, claws, scales, insects, feathered beings, leafed beings, mycelial networks. We’re part of this great family, and we ought to do our part to take care of these things.

Annabella Pitkin:

This picture has the Buddha teaching the animals among the animals. So animals are not actually left out. Buddhists across the Buddhist world are thoughtful about the needs that animals have for spiritual assistance from human beings. And a particularly beautiful example of that is the practice of life release where Buddhists buy animals who are destined to be killed for human food, and they pay to purchase them. And then they bring them somewhere like an animal sanctuary, where they can either be released into the wild or live a peaceful and safe life. And that practice is widespread across all the Buddhist worlds. And it’s a kind of solidarity between humans and animals that speaks to a deep repertoire of possibilities for ecological healing, for mutuality, for an understanding of the interdependent web of our common life in this biosphere that decenters the human from an egocentric place and returns the human to the role of companion, maybe even the role of relative to other kinds of living things.

Lyla June Johnston:

Sometimes the answers are not in the future. Sometimes they’re in the past, and sometimes the future is ancient because there’s a lot of codes, there’s a lot of compasses, there’s a lot of devices within not only indigenous material culture, but within our philosophical culture, philosophical, but within our philosophies as well that could really help us today. We were wealthy, and now we’re trying to get back to that.

Annabella Pitkin:

In this image, we see a very peaceable vision of the animal kingdom. Even the predators are not actually menacing. The grazers, the yaks are at the top. They look very happy there near their snow mountains. The fish are swimming in the sea. And so, even though this is seen as a rebirth that has severe limitations, often because of human action, the artist has shown us a kind of possibility of a biosphere and a world of living beings that are at peace and at harmony. And the Buddha’s presence in their midst really speaks to that.

Devendra Banhart:

Even small actions, practiced consistently, can have a profound impact. Lyla June, shares another beautiful practice.

Lyla June Johnston:

One thing that all of us can do to honor our interdependence with mother Earth is to give a little bit of our food to her every day on the ground. Some people call this a spirit plate, some people call it an offering, but I think it’s really something we can all do. And there are many, many tribes out there who, before they take a bite of their food, they put some on the earth. And that sounds maybe silly or weird, or maybe useless, but what you’re doing is you’re, when you’re in a marriage, right, you can’t just come home, eat all the food, and go to sleep and never talk to your spouse, right? Like you have, ideally, you’re writing love letters, you’re bringing a rose from time to time. There’s a romance involved with love. And it’s not always about something practical or something useful, but it’s about an emotional acknowledgement of how much you care about that person.

And that is, I think, what we’re doing when we give these offerings, right? Like, we are writing little love notes on the earth in the form of whether it’s corn meal, as my people do, or whether it’s a little piece of your burger, even , something is gonna eat that, whether it’s an ant or a bird or what have you. And that is your love note to creation saying, Hey, I’m here. I see you. And I believe Mother Earth can feel that. I could believe she can feel when her children are giving her little offerings. I believe she, it’s, it’s not necessarily the physical part of it, it’s the intention behind it that she feels and that makes her happy to have her children caring. And of course, there’s bigger things we can do than that to be in reciprocity and to live our interdependence with the earth.

Nicholas Christakis:

Life is an emergent property of matter.

Devendra Banhart:

Again, Nicholas Christakis.

Nicholas Christakis:

You take carbon and hydrogen and oxygen and sulfur and nitrogen and a little bit of iron and some other trace elements, and you mix them together and just the right way you get life. She’s astonishing. And consciousness is an emergent property of neurons. You take an individual neuron doesn’t have a thought, and separated neurons don’t have thoughts. But if you connect the neurons just right, you get consciousness, which is a current, an astonishing thing. So this idea of emergence, which arises because of interconnection and because of interdependence, is a very deep and profound observation.

Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche:

Buddha talk about like planting the trees, making the bridge and keeping the path.

Devendra Banhart:

Tibetan Buddhist meditation teacher and author, Mingyur Rinpoche.

Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche:

So when I was young, there’s a forest near my home. If I walk about 15 minutes I will be in the deep forest. Now the forest is gone. So everybody cuts trees and now we try to kind of, me and my my brother, we try, you know, help local people and also local people sometimes they need to have some income. So now we make kind of like we help the local people. There’s some berry like a rose hip, that teaches local people how to make tea and sell to the big company and all the profit go directly to the local special women’s in, in the region. So they work only two weeks and get 30 to 40,000 ru Nepal rubies. So then later they really wanna plant that tree everywhere because it get income, you know. So then local people plant the trees and tree can get income for the local people. So we think about this interdependent and then we make a lot of greenhouses also. And this greenhouse really helps local people, healthy food and then not too much plastic bags and the all this coming from the down level. So sometime when we think too much of a environment, the local people suffer if you help local people damage environment. So if you can make some kind of like interdependent way, I think that really helps.

Lyla June Johnston:

Now is the time to plant your dreams, to dream big and to come together, to work together and to set out what your principles are and see who comes to stand next to you. We all have our piece of the puzzle that contributes, I think that’s really what we’re being called to do right now. And it’s what we’re gonna do either way. It’s either like, do we wanna do it voluntarily or we wanna do it ’cause we have no other choice ’cause everything is failing around us. So, I’m really optimistic about the future because I think this Mother Earth is actually designed to repel corruption. It’s designed to crumble corruption. And I think that this earth is designed to house love. It’s designed to house unity and it thrives when people are in a state of equality, not only between humans, but between all life. And when we find that bio egalitarianism, this equality of all life, we will be very supported by the earth. ’cause I think that’s actually what she’s designed to house.

Devendra Banhart:

Take a look around you, outside, and remember you are intimately connected to the trees, the bugs, the animals, the sky. What you do affects it all, and vice versa. We are in a relationship, and with that comes the potential for us to do great harm but also the power to help sustain our beautiful world.

You just heard the voices of Nicholas Christakis, Lyla June Johnston, Annabella Pitkin, and Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche.

I am Devendra Banhart, singer, songwriter, artist, and your host.

To see the artwork discussed in this episode, go to rubinmuseum.org/wheel.

If you’re enjoying the podcast, leave us a review wherever you listen to podcasts, and tell your friends. For more stories and news from the Rubin, follow us on Instagram @rubinmuseum and sign up for our newsletter at rubinmuseum.org.

AWAKEN season 5 is an eight-part series from the Rubin.

AWAKEN is produced by the Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art with Kimon Keramidas, Gracie Marotta, Christina Watson, and Sarah Zabrodski in collaboration with SOUND MADE PUBLIC including Tania Ketenjian, Philip Wood, Alessandro Santoro, and Aaron Siegel.

Original music has been produced by Hannis Brown with additional music from Blue Dot Sessions.

AWAKEN Season 5 is sponsored by The Prospect Hill Foundation and by generous contributions from the Rubin’s Board of Trustees, individual donors, and Friends of the Rubin.

This program is supported, in part, by public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, in partnership with the City Council.

Thank you for listening.

One of the places we see interdependence at play most clearly is in the natural world. Within our interconnected relationship to the environment comes the potential for humans to sustain great beauty but also create great harm. What does it look like to live in mutual reciprocity with the Earth in small but meaningful ways?

For centuries people have turned to the image of the Wheel of Life to better understand cause and effect and the very nature of existence. The section of the Wheel depicting the animal realm is the focus of this episode’s exploration of ecology.

This episode features Indigenous musician, author, and community organizer Lyla June Johnston. AWAKEN season 5 is hosted by singer, songwriter, and artist Devendra Banhart. Other guests in this episode include social scientist, physician, and professor Nicholas Christakis, professor of Buddhism and East Asian religions Annabella Pitkin, and Tibetan Buddhist meditation teacher and author Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche.

Wheel of Life, attributed to Lhadripa Rinzing Chungyalpa (b.1912, Sikkim–d.1977); Sikkim; c. 1930; pigments on cloth; Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art; C2004.21.1

One of the most important teaching tools in Tibetan Buddhism is the Wheel of Life, also known as the Wheel of Existence, which demonstrates the cyclical nature of life, death, and rebirth. The scenes within the wheel portray the laws of karmic cause and effect, illustrating how a person’s actions bring about positive or negative outcomes in their current and future lives.

The focus of this episode is the animal realm. While this vignette depicts the animals living a seemingly delightful existence, Buddhist philosophers and teachers explain that the animal realm is one of considerable suffering. Animals are often tortured and harmed, killed and eaten, and made into slaves by human beings who are extremely cruel to them. Being reborn as an animal is especially frightening in a world dominated by humans. Animals have little power to influence the larger world around them and are often the first to feel the effects of human development and environmental destruction. In Buddhist philosophy, animals have feelings and empathy, but unlike humans, they do not have the intellectual capacity to do anything to alleviate their suffering.

Devendra Banhart is an internationally renowned musician considered a pioneer of the “freak folk” and “New Weird America” movements. Banhart has toured, performed, and collaborated with Vashti Bunyan, Yoko Ono, Os Mutantes, the Swans, ANOHNI, Caetano Veloso, and Beck, among others. His musical work exists symbiotically alongside his pursuits in the other fine arts including painting, poetry, and drawing. The Venezuelan American has released 11 albums. His drawings and paintings have appeared in galleries all over the world, including the Art Basel Contemporary Art Fair in Miami; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; Palais des Beaux-Arts in Brussels; Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles; Nicodim Gallery; and Serralves.

Dr. Lyla June Johnston (a.k.a. Lyla June) is an Indigenous musician, author, and community organizer of Diné (Navajo), Tsétsêhéstâhese (Cheyenne), and European lineages. Her multi-genre presentation style has engaged audiences across the globe toward personal, collective, and ecological healing. She blends her study of human ecology at Stanford, graduate work in Indigenous pedagogy, and the traditional worldview she grew up with to inform her music, perspectives, and solutions. Her doctoral research focused on the ways in which pre-colonial Indigenous Nations shaped large regions of Turtle Island (a.k.a. the Americas) to produce abundant food systems for humans and non-humans.

Nicholas A. Christakis, MD, PhD, MPH, is the Sterling Professor of Social and Natural Science at Yale University. His work is in the fields of network science and biosocial science. He directs the Human Nature Lab and is the co-director of the Yale Institute for Network Science. He was elected to the National Academy of Medicine in 2006; the American Association for the Advancement of Science in 2010; the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2017; and the National Academy of Sciences in 2024.

Annabella Pitkin is associate professor of Buddhism and East Asian religions at Lehigh University. Her research focuses on Tibetan Buddhist modernity, Buddhist ideals of renunciation, miracle narratives, and Buddhist biographies. She received her BA from Harvard University and PhD in religion from Columbia University. She is the author of Renunciation and Longing: The Life of a Twentieth-Century Himalayan Buddhist Saint, which explores themes of non-attachment and teacher-student relationship in the life of Khunu Lama Tenzin Gyaltsen. More →

Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche is a recognized tulku of the Kagyu and Nyingma lineages of Tibetan Buddhism, a teacher, spiritual leader, and bestselling author. He possesses the rare ability to present the ancient wisdom of Tibet in a fresh, engaging manner. His profound yet accessible teachings and playful sense of humor have endeared him to students around the world. Rinpoche’s teachings weave together his own personal experiences with modern scientific research in relation to the practice of meditation. He has authored several books including two bestsellers: The Joy of Living: Unlocking the Secret and Science of Happiness, which has been translated into over 20 languages, and In Love with the World: A Monk’s Journey Through the Bardos of Living and Dying. His recent TED Talk is titled “How to Tap into Your Awareness—and Why Meditation Is Easier Than You Think.” Rinpoche teaches extensively around the world and oversees dharma centers, including three monasteries in Nepal, India, and Tibet, and the Tergar Institute in Kathmandu; Tergar meditation communities on six continents; numerous schools in Nepal; and social engagement projects related to health, hunger, hygiene, the environment, and women’s empowerment issues in the Himalayas.

Get the latest news and stories from the Rubin, plus occasional information on how to support our work.