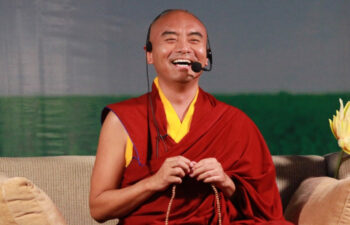

Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche:

In my village, I was born in Nepal, the spiritual practice is Buddhist culture and spiritual is based on the Buddhist.

Devendra Banhart:

Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche is a renowned meditation teacher, author of several books on Buddhism, and head of the worldwide Tergar Meditation Community.

Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche:

So we have a lot of art like each, everywhere. In the house, they have shrine, little shrine, there’s a lot of painting, statues, sculptures. People are learning the meaning of Buddhist teaching through art, through dance, through song, sculpture, paintings.

Devendra Banhart:

Welcome to season 5 of AWAKEN, a podcast from the Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art about the dynamic path to enlightenment and what it means to “wake up.”

I am Devendra Banhart, singer, songwriter, artist, and your host. In this season, we hear from experts in the realms of art, social science, Buddhism and more to better understand how interdependence is the foundation of every aspect of our lives.

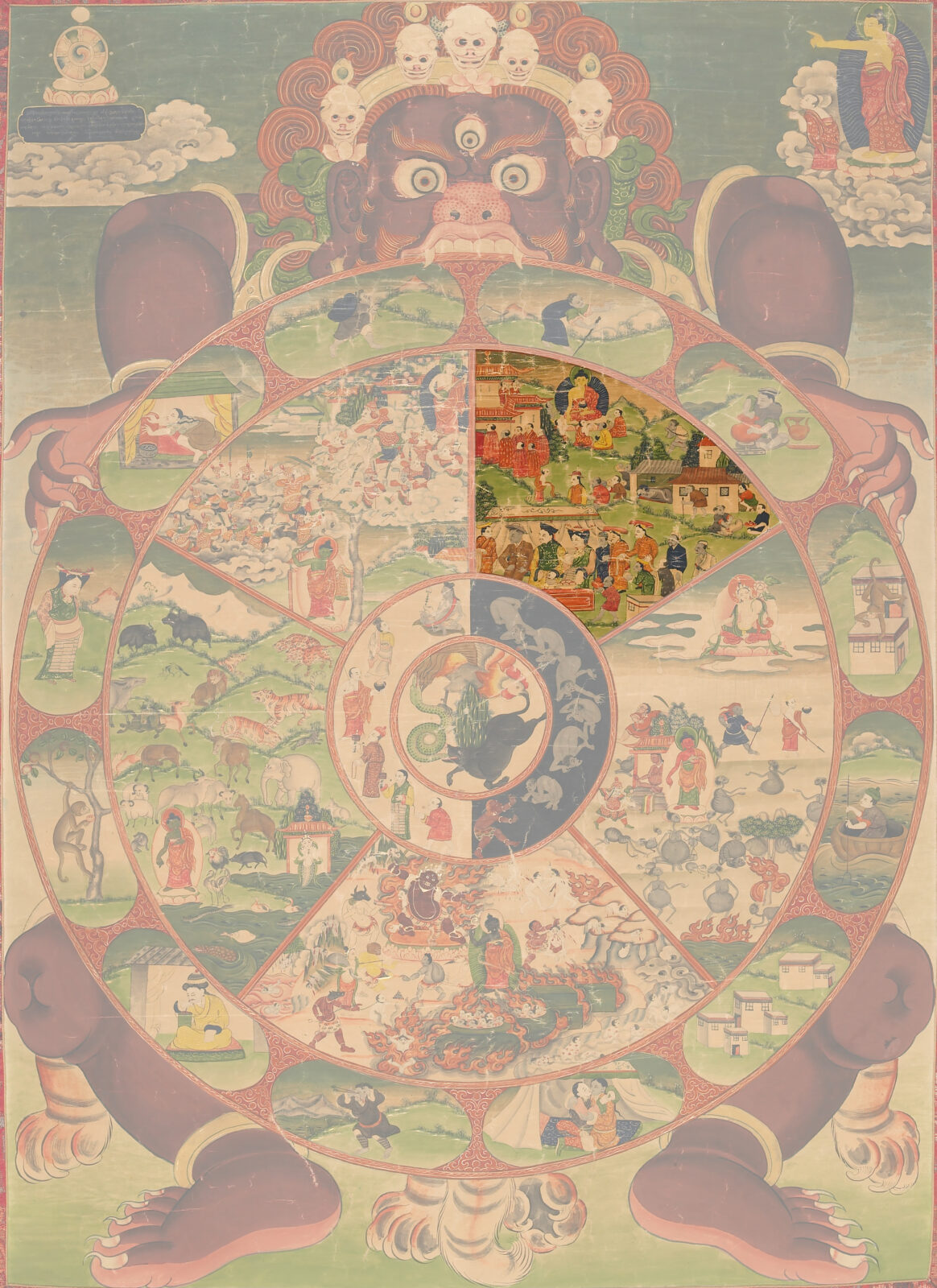

Himalayan art has long been a pathway to insights and awakening, and over the course of eight episodes we look specifically at a painting of the Wheel of Life to see what it can teach us about the interconnected nature of existence.

Throughout this journey, we’ll discover how greater awareness of our interdependence can be the wake up call that motivates us to take actions for a better world.

In this episode, we look at the ways art and culture reflect and deepen our understanding of interdependence. And in this episode, I’ll play two roles. I’ll not only be your host, but I’ll also share some of my personal connection to this topic.

I first started recording when I was 18 and went to art school thinking I was just going to be a painter and just do a little music on the side. It felt like whatever I was trying to express couldn’t fully be done with a song and couldn’t fully be done with a drawing or a painting. So it felt like the songs were being finished as a drawing or finished as a song. So you start the drawing, and I don’t know how to finish this. And then it was really clear that, oh, this song is how you finish that drawing. The feeling of interconnectedness is most palpable when you’re having a conversation with a friend and then you continue it with an instrument. Whoa, that’s a magical thing.

Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche:

The art in Buddhism, we talk about the five aggregates. The first is the matter, second is the feeling. Third is what we call concept.

Devendra Banhart:

Again, Mingyur Rinpoche.

Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche:

The fourth is the mental events. Last is the consciousness. But number three is what we call the concept meaning the making of the mark.

So, for example, company nowadays has to have logo. And the logo is very important. Wherever the company goes, the logo, they put the logo and people think about the company through the logo. That’s the mark, the conceptual mind. So art is some different form of that image, the labeling and emotional feeling mixed together to express different meaning.

Devendra Banhart:

This season, the artwork we’re focusing on is a painting of the Wheel of Life in the Rubin Museum’s collection. The Wheel of Life, also known as the Wheel of Existence, is a foundational symbol in Buddhism and offers a visual representation and reminder of the cycle of life, death, and rebirth. Part of the wheel depicts the six realms of existence where it is possible to be reborn. To see the artwork in detail, go to rubinmuseum.org/wheel.

Here, Professor Annabella Pitkin, who teaches Buddhism and East Asian religions at Lehigh University, looks at the human realm. In this realm the capacity for imagination and culture is part of what gives rise to art.

Annabella Pitkin:

This Tibetan artist reminds the viewer that the precious ideas of Tibetan Buddhism come from the specific cultural context of Tibetan, the Tibetan Himalayan world. And at the same time, this is a universal panel. This is a picture of the global community of human beings, the most macro community we can imagine, because all beings have the capacity according to this interdependent dynamic model of the universe to arrive in the human realm. And the human realm is described as the best possible state that we could be in. It is a mixed bag, and the Buddhist traditions are very direct about it being a mixed bag. We experience suffering and fear and pain, and we make mistakes in our human experiences. However, we have the capacity to imagine happiness and freedom, and we have the capacity to experience love and care. And we have the intelligence and the knowledge and the wisdom and the insight to realize our interdependence and connection.

Devendra Banhart:

Contemporary artists continue to explore questions that are of time immemorial, like who we are, and how we connect with one another. Osheen Siva is an interdisciplinary artist and visual storyteller based in Goa, India. Their vibrant, colorful work spans several mediums, including painting, drawing, performance art, and public art. Much of it is rooted in their Dalit and Tamil heritage. Osheen also created the cover art for the Interdependence issue of the Rubin Museum’s annual Spiral magazine. You can see it at rubinmuseum.org/spiral

Osheen Siva:

When I was approached to visually depict the word interdependence, I associated it with interconnectedness and I’ve been working with the idea of interconnectedness in my work as well in two distinct ways. One is sort of the ecological side of it, and another is the sociocultural side.

I’ve always been interested in interconnected things that you see naturally, like the mycelium and the mushroom formations underground and how they support each other. And so I’ve used that kind of as a metaphor in my works before to evoke a sense of community and interchanging and interconnected of things as humans, but also our connection with nature.

The other aspect of it is also interesting to me, other than ecology and equity and things like that, I’ve also been exploring the oppressed-caste community and so it’s interesting to see caste as a way that’s fortified through different means of quote unquote justifications—some of them historical, some of them political. It’s interesting to see the background of how it has evolved over time, not just in India, but also trans nationally, the perpetuation of caste, but also anti-caste movements. So I’ve been kind of interested in solidarity between communities, between spaces that are divided by borders between different disciplinaries.

Devendra Banhart:

Osheen wants to address topics that may be difficult to express in words through their work. Art can capture ideas and concepts and make them more understandable, more tangible.

Annabella Pitkin:

It’s a wonderful way for people whether or not they want to read or can read Buddhist texts to have a snapshot of the most important Buddhist teachings all in one image.

Devendra Banhart:

Again, Annabella Pitkin on the Wheel of Life.

Annabella Pitkin:

And so the kind of feeling of familiarity, of recognizability, of it being local, that feeling is something that this image was originally intended to convey. And we can kind of translate that in our own minds, even if this doesn’t feel specifically familiar to us. Now, we can remind ourselves this human realm is our human realm. And I could see myself there reminding me that in this presentation of interdependence, it is possible from the affordances of the human realm to pursue an extraordinary kind of compassion and insight into reality and freedom from suffering.

Osheen Siva:

We’re all just trying to exist. At the end of the day, a lot of it, like people’s jobs are connected, we’re interconnected in ways that help us move as a society.

A lot of my compositions are generally character based. They have characters that represent certain philosophy or they play as a metaphor for something else. And so in this cover you can see two characters facing away from each other, but their hair is braided together. They also have symbols and elements like the mycelium and root structures and planets that orbit them. And so all these smaller elements for me were representations of interconnectedness. Planets, for instance, the fact that we’re all kind of existing within this orb or roots that connect one to each other. And mycelium. And also the idea of braiding, which is like a pattern and a vision that I’ve seen very often growing up. It’s such a ritual in an Indian family household where grandparents and aunts sit together in the evening and oil each other’s hair, or braid each other’s hair. So that played as a symbol for me, as like familial interactions and intimacy and kind of passing down of knowledge and care. And so that was an easy place to kind of explore. The cover has these two characters with their hair and other natural elements that are interconnected within themselves.

Devendra Banhart:

Osheen Siva created a contemporary interpretation of interdependence. And as Annabella PItkin points out while looking at the human realm in the Wheel of Life, even art created long ago, in a much different era, can remain relevant across time.

Annabella Pitkin:

The image is extremely detailed and it’s difficult to see with perfect clarity, all of the fine, fine, details that the painter has added. But it looks to me like the furthest left figure may be wearing monastic robes and may be speaking to the group of beautifully dressed, perhaps important or wealthy or perhaps in their finery, their best clothes, people who are coming perhaps for a Buddhist teaching. At the very, very bottom, there seems to be a tiny little monk, maybe a child, maybe just foreshortened for the perspective. And we see a central, uh, pair who seemed to be a couple, a man in a green tunic with yellow sleeves and a black hat, and what may be a woman with beautiful traditional jewelry in her hair and a tuba with yellowish sleeves and a kind of green and gold pattern. And it’s not impossible that those are in fact, individuals who had something to do with the commissioning of this image, although I wouldn’t wanna go out on a limb and insist that that’s the case. But there’s a hint there, perhaps of some actual people. At the very least, a viewer would know that these are familiar human beings dressed in recognizable and familiar clothes. And so one of the things that we might think about when we look at this image is that even if this particular portrait of a Tibetan community, perhaps in the midst of going to a religious teaching, even if that doesn’t culturally specific for us at this moment, it is an example of something familiar for the thousands and thousands of viewers that this kind of image was designed to teach. Because the wheel of life is a teaching image.

Devendra Banhart:

Images of the Wheel of Life often hang outside temple and monastery walls, so anyone can see and learn from them. Much like a public art project, there is an interconnected relationship between the artwork, the setting, and the people walking by.

Osheen Siva:

I love working in the public. Generally, when I’m making, installations or mural work, they are very much situated in the community or the area in which the piece exists themselves. And so it’s nice to be able to engage with that immediate community. There’s also an aspect of it where as a viewer, you take what you want from it, which I find fascinating. And that’s the interesting thing about interacting with a piece. When you’re interacting with it, you come in with your own ideas, your own thoughts, your own situation and positionality, and you look through it with your sense of being. So when my artworks are being viewed for someone else, I get a lot of interpretations that I didn’t necessarily mean sometimes, but it’s interesting to understand how it’s being perceived or how it’s being engaged with a lot of times, especially public art, right? Once it’s out, you don’t have any power over it anymore. It’s very democratic in a way. It’s also very accessible. It is going to be viewed in ways that are unpredictable which is nice and interesting.

A lot of times people are just kind of intrigued to know more, which is a nice way, at least for me, to be able to think of it as like a gateway into knowing more about what the art actually depicts. Or hopefully the audience is interested to know the background of what the piece is trying to depict. Also the couple of murals that I’ve made in the past, it just happens to be next to schools. So a lot of times the school kids will come and be kind of intrigued about what is going on, and by the virtue of my work being kind of flat colors, one is able to add on to it as well. So a lot of times there, there’s been some kids like helping me paint the background colors and things like that, which is always so nice.

Devendra Banhart:

Art is inherently interdependent. It can’t exist in a vacuum, but comes to life and takes on meaning through the people seeing and engaging with it. And hopefully, it also inspires you to see and understand the world in new and profound ways.

I’m excited to share what interdependence means to me as a musician, artist, human being.

It becomes really graceful and terrifying and inspiring and otherworldly kind of when you’re doing it in a musical context, at least for me, especially live. It’s the whole other thing. Talk about psychic energy, just a whole crowd of people in the whole thing and how that feels and how you have to kind of one sense fight it. And the other sense you want to open the bridge and be a part of it, and there’s a lot going on, and that’s really an interconnectedness that’s happening without any conversation. When those moments happen, when you’re like, wow, I’m really connecting here, and we have this taking off feeling, I guess it’s a very high transcendent feeling. It really is, and it is a losing yourself in something. It’s that flow state feeling, and it’s also a breakout through kind of feeling you suddenly enter this powerful space.

Annabella Pitkin:

Pictures of this kind show the interdependence that is the true nature of reality, the freedom from that whole web of deathly obsession with one’s own ego. So from the Buddhist perspective, the painting is saying a different experience of ourselves in reality is always possible. The experience of freedom, the recognition of interdependence, the compassionate wish to help others, that’s actually already present. It’s copresent with the wheel, it’s represented simultaneously with the wheel, and it’s always available and accessible.

Devendra Banhart:

You just heard the voices of Annabella Pitkin, Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche, and Osheen Siva.

I am Devendra Banhart, singer, songwriter, artist, and your host.

To see the artwork discussed in this episode, go to rubinmuseum.org/wheel.

If you’re enjoying the podcast, leave us a review wherever you listen to podcasts, and tell your friends. For more stories and news from the Rubin, follow us on Instagram @rubinmuseum and sign up for our newsletter at rubinmuseum.org.

AWAKEN season 5 is an eight-part series from the Rubin.

AWAKEN is produced by the Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art with Kimon Keramidas, Gracie Marotta, Christina Watson, and Sarah Zabrodski in collaboration with SOUND MADE PUBLIC including Tania Ketenjian, Philip Wood, Alessandro Santoro, and Aaron Siegel.

Original music has been produced by Hannis Brown with additional music from Blue Dot Sessions.

AWAKEN Season 5 is sponsored by The Prospect Hill Foundation and by generous contributions from the Rubin’s Board of Trustees, individual donors, and Friends of the Rubin.

This program is supported, in part, by public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, in partnership with the City Council.

Thank you for listening.

The interconnected relationship between artist and viewer is what gives art its meaning and power. Art can capture ideas that are difficult to express in words and make them more understandable. How do artists reflect and deepen our understanding of interdependence?

For centuries people have turned to the image of the Wheel of Life to better understand cause and effect and the very nature of existence. The section of the Wheel depicting the human realm is the focus of this episode’s exploration of culture.

This episode features interdisciplinary artist and visual storyteller Osheen Siva. AWAKEN season 5 is hosted by singer, songwriter, and artist Devendra Banhart. Other guests in this episode include professor of Buddhism and East Asian religions Annabella Pitkin, and Tibetan Buddhist meditation teacher and author Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche.

Wheel of Life, attributed to Lhadripa Rinzing Chungyalpa (b.1912, Sikkim–d.1977); Sikkim; c. 1930; pigments on cloth; Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art; C2004.21.1

One of the most important teaching tools in Tibetan Buddhism is the Wheel of Life, also known as the Wheel of Existence, which demonstrates the cyclical nature of life, death, and rebirth. The scenes within the wheel portray the laws of karmic cause and effect, illustrating how a person’s actions bring about positive or negative outcomes in their current and future lives.

This episode explores the human realm section of the Wheel. Despite the difficulties and imperfections of being human, Buddhists believe it is the most auspicious birth, as well as one of the rarest, because humans have the time and intelligence to seek enlightenment. Human life is not the pleasure trap of godhood, the daily struggle of animal life, or the tortured existence of the hell and hungry ghost realms. Humans have the capacity for change and are uniquely situated to transform their situations. This depiction of the human realm is a beautifully idealized and culturally specific portrait of a community in the Himalayan world, as well as a representation the human world writ large.

Devendra Banhart is an internationally renowned musician considered a pioneer of the “freak folk” and “New Weird America” movements. Banhart has toured, performed, and collaborated with Vashti Bunyan, Yoko Ono, Os Mutantes, the Swans, ANOHNI, Caetano Veloso, and Beck, among others. His musical work exists symbiotically alongside his pursuits in the other fine arts including painting, poetry, and drawing. The Venezuelan American has released 11 albums. His drawings and paintings have appeared in galleries all over the world, including the Art Basel Contemporary Art Fair in Miami; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; Palais des Beaux-Arts in Brussels; Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles; Nicodim Gallery; and Serralves.

Osheen Siva is a multidisciplinary artist, originally from Thiruvannamalai and currently based in Goa, India, who engages with themes of identity, futurism, and resistance through the prisms of surrealism, speculative fiction, and science fiction. Grounded in their Dalit and Tamil heritage, Siva envisions transformative narratives of decolonized dreamscapes, futuristic oases, and empowered queer and feminine identities, often inhabited by mutants and mythical beings. Their diverse practice spans immersive media, installation, performance art, public art, and digital illustration. See their work @osheen.siva and osheensiva.com

Annabella Pitkin is associate professor of Buddhism and East Asian religions at Lehigh University. Her research focuses on Tibetan Buddhist modernity, Buddhist ideals of renunciation, miracle narratives, and Buddhist biographies. She received her BA from Harvard University and PhD in religion from Columbia University. She is the author of Renunciation and Longing: The Life of a Twentieth-Century Himalayan Buddhist Saint, which explores themes of non-attachment and teacher-student relationship in the life of Khunu Lama Tenzin Gyaltsen. More →

Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche is a recognized tulku of the Kagyu and Nyingma lineages of Tibetan Buddhism, a teacher, spiritual leader, and bestselling author. He possesses the rare ability to present the ancient wisdom of Tibet in a fresh, engaging manner. His profound yet accessible teachings and playful sense of humor have endeared him to students around the world. Rinpoche’s teachings weave together his own personal experiences with modern scientific research in relation to the practice of meditation. He has authored several books including two bestsellers: The Joy of Living: Unlocking the Secret and Science of Happiness, which has been translated into over 20 languages, and In Love with the World: A Monk’s Journey Through the Bardos of Living and Dying. His recent TED Talk is titled “How to Tap into Your Awareness—and Why Meditation Is Easier Than You Think.” Rinpoche teaches extensively around the world and oversees dharma centers, including three monasteries in Nepal, India, and Tibet, and the Tergar Institute in Kathmandu; Tergar meditation communities on six continents; numerous schools in Nepal; and social engagement projects related to health, hunger, hygiene, the environment, and women’s empowerment issues in the Himalayas.

Get the latest news and stories from the Rubin, plus occasional information on how to support our work.