Kabi Raj Lama, in collaboration with Dr. Sujaya Neupane; Construction and Destruction; 2023; lithography; courtesy of the artist; photograph by Dave De Armas

Kabi Raj Lama, in collaboration with Dr. Sujaya Neupane; Construction and Destruction; 2023; lithography; courtesy of the artist; photograph by Dave De Armas

Why do bad memories stick? Why can’t we unthink and not brood over that awful event? The survival mechanism that helped organisms avoid life-threatening circumstances for millennia seems to have ironically helped engender, in the present day, morbid states of mental illness.

At a larger scale, why do societies often behave in antiquated ways despite individuals being aware of the legacies of structural inequities? To what extent do we have the power to contribute to positive change—both within ourselves and in the society we live?

We asked these questions as we embarked on our collaborative journey of turning to art and science for answers. Kabi Raj Lama has been practicing various forms of visual art since his childhood, initially as a painter in Kathmandu and eventually maturing as a printmaker. He is currently exploring novel print series at Rutgers University in his quest for abstract expressions. Kabi’s primary schoolmate, Sujaya Neupane, is a neuroscientist whose research aims to understand the neural mechanisms of how we use long-term memories to make decisions and take appropriate actions. Both of us have a common interest in understanding how arts and sciences can play positive roles in social transformation.

The nature of transformation is a complex interplay of disintegration and integration. Kabi repeatedly portrays this theme in his art. The Rubin Museum’s exhibition Reimagine: Himalayan Art Now features the artist’s Construction and Destruction (2023). The images of natural disasters and scaffolding are juxtaposed with a Rubin Museum sculpture of Manjushri, a bodhisattva who slashed open a gorge east of Kathmandu Valley to make habitation possible.

Manjushri; Tibet; 19th century; Metal alloy; Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art, Gift of Shelley and Donald Rubin; C2013.9a-c

The optimistic message here is that both individuals and societies go through tumultuous periods only to emerge more mature. We are far from an ideal, peaceful world, but progress can emerge from unprecedented damage. The progress humanity has made in the international justice system since World War II is an example, including the retributive justice system of the international tribunals, restorative justice imagined in the Truth and Reconciliation Commissions, and so on. In a similar vein, one can find examples of highly successful individuals whose pasts were filled with suffering.

Yet isn’t it unfair to analyze things in hindsight and offer kudos to unpleasant experiences that no one wants to experience or remember? Surely one wouldn’t intentionally opt for a more painful experience in hopes of a better future. What is then the active process of transformation? Where is the straight path on which we might march and triumph over our individual selves and the ills of society toward truth and justice? As we explored these questions, we encountered two powerful concepts—constructive agency and brain plasticity.

Detail of Construction and Destruction, showing images of construction juxtaposed with those of destruction symbolizing the interplay of integrating and disintegrating forces in social change

Detail of Construction and Destruction showing an image of a man with a tool symbolizing the act of constructive agency in the midst of disintegrating surroundings

We first explored Mahatma Gandhi’s ideas on social change. Gandhi, who championed the idea of nonviolent social change, is widely known as a pioneer of enacting civil disobedience. Although proven temporarily effective in the Indian independence movement in addition to other contexts such as the American Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s and the South African struggle against apartheid, civil disobedience was actually considered secondary to a more radical constructive program by Gandhi himself.

A constructive program is a process of engaging in active work towards building a just social order. The notion is that when communities start learning ways to participate in social life with concrete actions aiming to establish a new, just social order, the older shell that held the fabric of society with various forms of injustices crumbles on its own. This approach sounds so radical that it compares to no other means of attaining justice, especially in the face of our current culture of critique and contest. Gandhi is less known for his constructive program because he was unable to mobilize the masses. But other communities have deployed such an approach, such as the African American Cooperative Movement and North American Indigenous people.

The Bahá’í community offers an exemplary instance of constructive agency that started decades before Gandhi and continues to the present day. Although an independent world religion, Bahá’í Faith started as a seemingly obscure religious movement in Iran in the middle of the 19th century, but it has achieved unprecedented success in contributing to the discourse and practice of social change. Tarbiyat School for Girls’ Education, established in early 20th-century Iran, and the Bahá’í electoral system practiced around the world are just two examples of its constructive programs. From its inception the Bahá’í community has embodied constructive resilience in the face of oppression, taking action for the betterment of the world.

One particular idea in the Bahá’í discourse helped us relate to our original question. The concept of power in a constructive program is entirely opposite the more popular portrayal of power in the contemporary postmodern discourse, which focuses on the oppressive expressions of power. By analyzing the nature of power relations, so the contemporary discourse goes, in a dominator’s quest for domination, one can truly call out the oppressive social forces. A constructive program finds such a conception of power too narrow and instead focuses on the unifying and harmonizing capacity of the human spirit, not just individually but at the level of institutions and communities via creative actions. A natural question to us was—where is that power inside of me? How can an individual harness the power that lies within to let go of debilitating memories and fuel the desire to bring about change?

One source of the power to transform oneself is in our own biological system. The capacity of the brain to learn, and re-learn in case of injuries, is a well-known feature of our nervous system. The applicability of this latent capacity, however, has only recently begun to surface in the neuroscience literature. The previously well-established brain regions with specific functional roles seem to exhibit diverse other functions under the influence of specific behavioral training. Researchers have started exploiting the potential of brain plasticity and devising targeted behavioral strategies for restoring lost function after a brain injury like a stroke. One could then deduce that the brain that stores unwanted memories has the capacity to heal from those memories.

We drew a parallel between the emerging neurorehabilitation program that harnesses the latent potential of the brain to heal from neurological damage and the constructive program that harnesses the latent potential of individuals and communities to heal from societal ills. As we labored to find a productive link between the two powerful concepts, we realized that successful neurorehabilitation programs are common in cases of physical trauma to the brain. Healing programs for psychological trauma, whose physical substrates remain out of the reach of neuroscience, lag far behind. Neuroscientists don’t understand the anatomical and computational underpinnings of a bad memory. Only a fundamental understanding of the elusive psychological phenomena of long-term memory could provide a possibility of conceiving a therapeutic program.

We realized that the limits of science are where art comes in for a rescue.

As one of us turned to science to try to address this gap, we realized that the limits of science are where art comes in for a rescue, almost playing a spiritual role. We don’t mean magical when we say spiritual. Nor are we dualists. By spiritual, we simply mean something outside our current epistemological limit but something undoubtedly real. Art has the power to transcend such limits and, at times, evokes a sense of understanding not possible with a logical thinking trajectory. We proposed that art could play a crucial facilitatory role in healing from psychological trauma through constructive, creative action, and in the process, exploit brain plasticity.

To synthesize the ideas into a concrete project, we framed art and science collaboration as a project exploring the relationship between the subjective and the objective. The process of healing from psychological trauma is a subjective one. Existing methods try to tap into subjective experiences to find possible points of resolve to overcome the adverse effects of traumatic events. Art therapy is thought to be one of such methods. If the process of making art engages the brain’s capacity to change toward healing, can one study this process? What would an objective assessment of cognitive healing look like?

We hypothesized that creating art has a healing effect at certain moments of epiphany, occurring sporadically during the art-making process. Such a moment could be a visual artist drawing that perfect stroke or a poet composing that perfect line—both subjective in their aesthetic meanings, but objective in their effects on the mind and brain. To explore this hypothetical process, we envisioned creating a metaphorical mirror of the mind. We reasoned that if we monitor the brain activity as the artist creates, perhaps we can get a glimpse of the internal processes of creativity and healing manifested in the body. Can we objectively identify subjective moments of epiphanies?

As a first step, we set up a system to monitor the subtle movements of an artist’s eyes, head, and hands, as well as the tools they use to create art. We want to know if the effect of a creative process is manifested in the behavior of bodily movements as a dynamic change. If so, there must be a commensurate process in the brain driving the dynamic behavioral change. In the future, we could monitor brain activity and look for signatures of those changes in the brain. We could then ask if the time course of such changes correlates with the artist’s account of the joyful moments of creativity. Our hypothesis and ideas almost sound like science fiction, even to ourselves, but it has provided us with a framework to collaborate and explore the elusive relationship between the subjective and the objective.

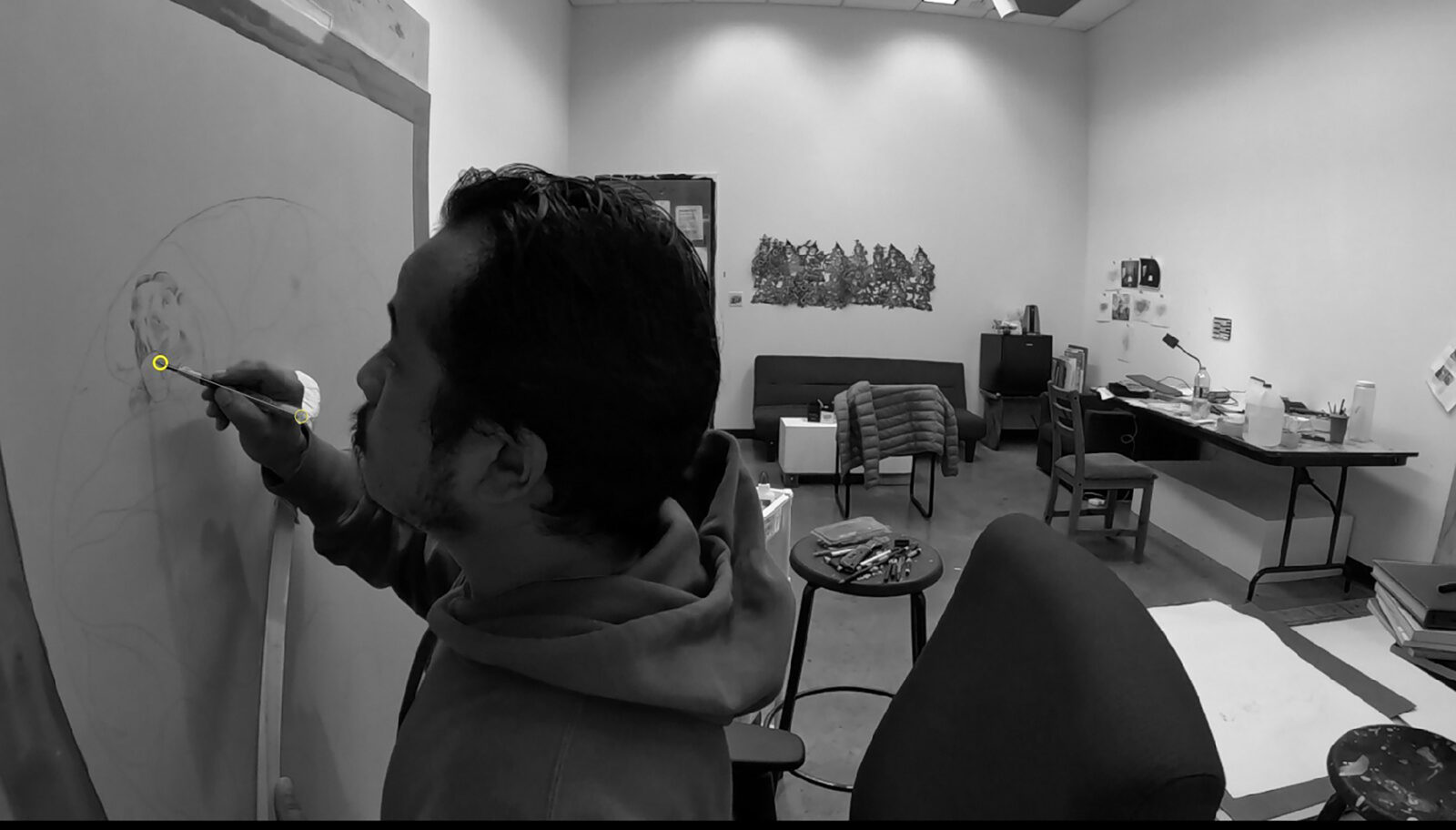

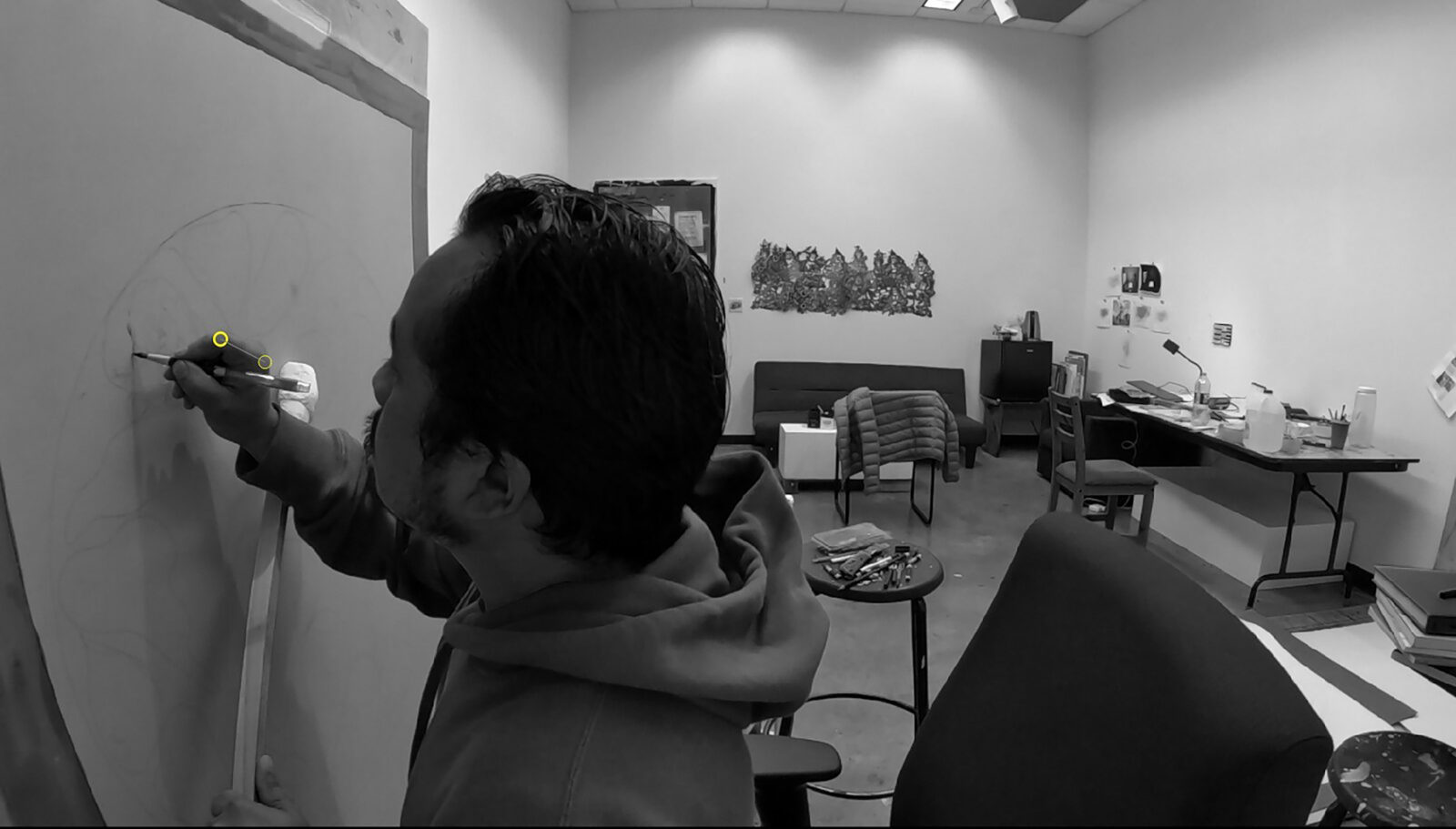

Automated tracking of the artist’s tool (left) and index finger (right) during the art-making process4

Automated tracking of the artist’s tool (left) and index finger (right) during the art-making process

Indeed, both of us have had firsthand experience of the healing effect of an art-making process. We concurred that we don’t magically let go of unpleasant memories, but they simply become irrelevant as a creative agent transforms a bad memory into good art, “ripening their spirit” in the process. The role that brain mechanisms play in such a high-level cognitive process remains hypothetical. Nonetheless, the process of our collaboration has offered us a way to expand our understanding of detachment and letting go.

Rather than an act in itself, detachment is a mental state, reached through constructive action, of viewing both good and bad experiences as integrating and disintegrating forces of an evolutionary process. Experiences may be pleasurable or painful on the surface, but underlying all is a force that can propel one to take creative action and contribute to progress individually and collectively.

Sujaya Neupane is a neuroscientist in the Department of Neuroscience at the University of Montreal and York University. He received his PhD in neuroscience from McGill University. Dr. Neupane specializes in computational neuroscience and uses neurophysiology and psychophysics experiments to answer questions on visual perception and cognition. He remotely mentors students in Nepal and established a collaboration at Tilganga Institute of Ophthalmology to facilitate this neuroscience training program.

Kabi Raj Lama works at the intersection of neuroscience and art. Descended from a line of Buddhist monks in the indigenous Tamang community in Nepal, he grounds his work in the ideals of his community. His personal experiences and interests overlap with notions of impermanence and science.

Kabi graduated from Kathmandu University in 2009, and in 2011 he went to Japan to study printmaking at Meisei University. He is currently based in New York and graduated from the MFA program at Rutgers University. His works have been exhibited at various international galleries, institutes, and museums, including Machida National Print Museum, Tokyo; Ome City Art Museum, Tokyo; Fukushima Biennale, Japan; National Art Gallery, Sofia, Bulgaria; Lakshima Mittal, South Asia Institute of Harvard University; Tianjin Art Museum, China; Nepal Art Now, Welt Museum, Vienna Austria; The Palace Museum, Beijing; and Today Art Museum Beijing.

Get the latest news and stories from the Rubin, plus occasional information on how to support our work.