Main printing room at the Derge Parkhang. There is no electricity in the building because of the danger of fire. Photo courtesy Dowdey/Meador/Padma’tsho

Main printing room at the Derge Parkhang. There is no electricity in the building because of the danger of fire. Photo courtesy Dowdey/Meador/Padma’tsho

For centuries the famed printing house has produced Buddhist books of impeccable quality and craftsmanship using woodblock printing

Woodcut printing flourished in Tibet in the 17th century, and it was almost immediately applied to the publication of classic Buddhist texts, at first smaller ones and then the most holy books of Tibetan Buddhism, the Kangyur and Dengyur.

Imagine craftsmen printing an entire book using only woodblocks. A calligrapher writes out each page for the engraver to paste on the board as a guide, then the engraver cuts each character backwards into a block (woodblock printing does not use movable type), an editor reads it to catch mistakes, and a more skilled engraver corrects it. Printing the blocks also takes a team: one to handle the paper, one to print, and a third to take blocks back and forth between the storage racks and printing station.

Now imagine using this process to print the Kangyur, a 122-volume book of the words of the Buddha, which believers revere as the body of the Buddha. Scholars and craftspeople at the Derge Parkhang printing house edited and then cut the blocks for the Kangyur between 1729 and 1733. In the following decades they completed the larger 224-volume Tengyur, the commentaries on the Kangyur. Nowadays they print ten copies of each every year, still only using woodblocks. A block cutter at the Parkhang once told me he tries to do his best, because a hundred years from now people will still be reading books printed from the blocks he cuts.

Man carrying a recently conserved title block to the Derge Prajnaparamita; photo courtesy Dowdey/Meador/Padma’tsho

Books are fundamental to Buddhism. For centuries, kings and monasteries sponsored scriptoria where monks hand-copied books and then donated the books to lamas, other kings, or monasteries. The donor gained merit, the receiver a great religious treasure. The famous 19th-century Derge editor Tsering Wanggyel wrote, “Since the Kangyur contained the words of the Buddha, producing it was tantamount to inviting Shakyamuni himself to visit Tibet.”

It could take a calligrapher years to copy even a moderately sized book. When errors crept in, they were repeated, as those books were used as models for later copies. Printing books had obvious advantages, and after the technology arrived in Tibet it spread quickly.

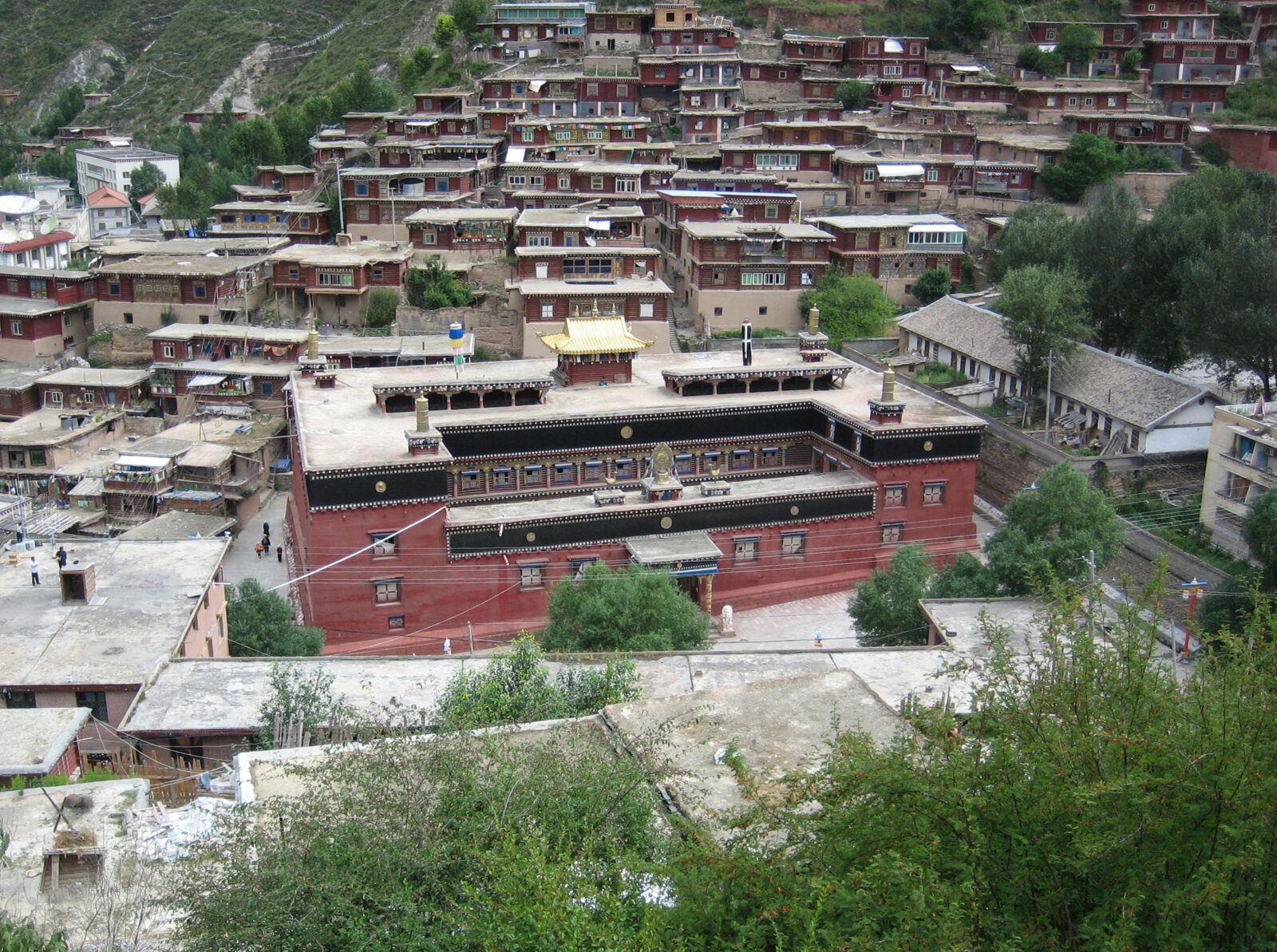

The Derge Parkhang (also called the Derge Sutra Printing Temple) is one of the foremost cultural, religious, social, and historical institutions in the Tibetan cultural world. Founded in 1729 by the fortieth King of Derge Tenpa Tsering (1678–1739), the Derge Parkhang is an active center for publication of the Kangyur and Tengyur, as well as the Five Sakya Ancestors, the Genealogy of the Kings of Derge, medical, religious, and musical texts, and hagiographies, religious commentaries, and sutras. The printing house is located in Sichuan’s Ganzi Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture close to its border with the Tibetan Autonomous Region in the area of eastern Tibet called Kham. It is the only survivor of the three historic Tibetan printing temples (the other two were in central Tibet at Narthang near Shigatse and the Shol in Lhasa).

Woodcut portrait of the fortieth King of Derge and founder of the Derge Parkhang Tenpa Tsering (1678–1739); image courtesy Dowdey/Meador/Padma’tsho

Three hundred thousand woodblocks are housed at the Derge Parkhang, most of them cut in the 18th and 19th centuries and many in active use. Scholars say that 70 percent of the Tibetan literary heritage is represented on the woodblocks at Derge. It is also home to a significant collection of woodblocks for printing thangkas, prayer flags, mandalas, and other spiritual images, some of which are older than the Parkhang itself.

Every year the Parkhang produces ten copies each of the Kangyur and Tengyur, as well as other books in its collection, for Buddhists in Tibet and inner China. Scholars and monasteries buy books, and lay people place woodcut copies of the Derge Kangyur and Tengyur in stupas and home chapels. The Parkhang increasingly distributes books overseas to individuals and cultural institutions: the New York Public Library recently acquired a complete set of the Kangyur and Tengyur.

As one of the most important and revered institutions in eastern Tibet, the Derge Parkhang holds a unique position in the social and religious life there, a living institution for the preservation of traditional Tibetan Buddhism and Tibetan cultural traditions. Derge Parkhang books and prints represent a summit of the Tibetan woodcut tradition.

The Derge Parkhang; photo courtesy Dowdey/Meador/Padma’tsho

The story of the Derge Parkhang begins in the late 17th century, when kings and monasteries in Tibetan areas started to bring smaller chiefdoms and monasteries under their control. The Gonchen (Derge) monastery Abbot Sanggye Tenpa (1638–1710) enlarged the royal family’s territories to the south through patronage of influential religious leaders. He also commissioned a woodcut production of the Prajnaparamita (The Perfection of Wisdom), not a large book but richly illustrated and, like the later Kangyur, always printed in cinnabar because it is the words of the Buddha. It is certainly the most beautiful book at Derge.

The Prajnaparamita and the Five Sakya Ancestors were edited by the Situ Panchen Chokyi Jungne (1700–1774) at Palpung monastery in Derge. In the 1720s Sanggye Tenpa’s nephew, the tenth King of Derge and fifth Gonchen Abbot Tenpa Tsering (1678–1739), annexed seven more neighboring territories. These increases in territory enriched Derge and expanded its population considerably.

Shrine to the Derge Parkhang’s patron, the Green Droma; photo courtesy Dowdey/Meador/Padma’tsho

The royal family’s support led to the growth not only of Gonchen but also Palpung where Situ Panchen started work on the ambitious Kangyur publication project. It meant scaling up—the Prajnaparamita and Five Sakya Ancestors were already successful printing projects, but publication of the much larger Kangyur required more scholars, craftsmen, space, and materials. Tai Situ Tsultrim Rinchen (1697–1774), a scholar who had worked and studied in central Tibet, joined Situ Panchen Chokyi Jungne at Palpung during production of the Kangyur and then continued that work with the Tengyur, adding a long index of his own. Because of the quality of his work people referred to him as the Great Editor.

Woodcut portrait of the Eighth Situ Panchen Chokyi Jungne (1700–1774), editor of the Derge Kangyur; image courtesy Dowdey/Meador/Padma’tsho

Tai Situ and Situ Panchen brought together scholars from all parts of the Tibetan world and trained them to edit books for publication at Derge. Historic texts were compared, checked and edited before they went to the calligrapher, checked again before cutting, and then the blocks themselves proofed before being given to the printers. As a Tibetan monk said, “Books from Derge are simply flawless; they represent unquestionable accuracy.”

Monk calligraphers who had worked in scriptoria came to make the calligraphic masters for the block cutters to use. Mani stone carvers from the Derge district of Jomda found the shift to cutting woodblocks relatively easy: apprentices did the rough cut, better cutters finished it, and the best of them made the corrections.

There is a story that when Tenpa Tsering wanted to assure the quality of the work on the blocks, he paid the cutters by filling the cut board with gold dust: the deeper the cut, the more gold dust. You can easily believe it’s true when you see the blocks for Derge’s most famous books. All played an important part in the brilliant cultural florescence in the Kingdom of Derge.

Through the later 18th and 19th centuries, the scholarship and skills at Derge continued to develop. Printing books from older blocks continued while new ones were edited and published, including Tsewang Dorje Rigzin’s Genealogy of the Kings of Derge. In the mid-19th century, Derge emerged as a center for the ecumenical rimé movement led by Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo (1820–1892) and Jamgon Kongtrul (1813–1899). Their compilation of the teachings of the Sakya, Kagyu, and Nyingma traditions included many near-extinct teachings and were disseminated through publication at the Parkhang.

The Parkhang’s preservation during the Democratic Reforms in 1958 and then its reopening in the early 1980s played an important role in the revival of Tibetan Buddhism during China’s reforms, providing books and scholarship for reopened monasteries, religious groups, and study. The Derge Parkhang continues to serve as a functioning educational publishing institution.

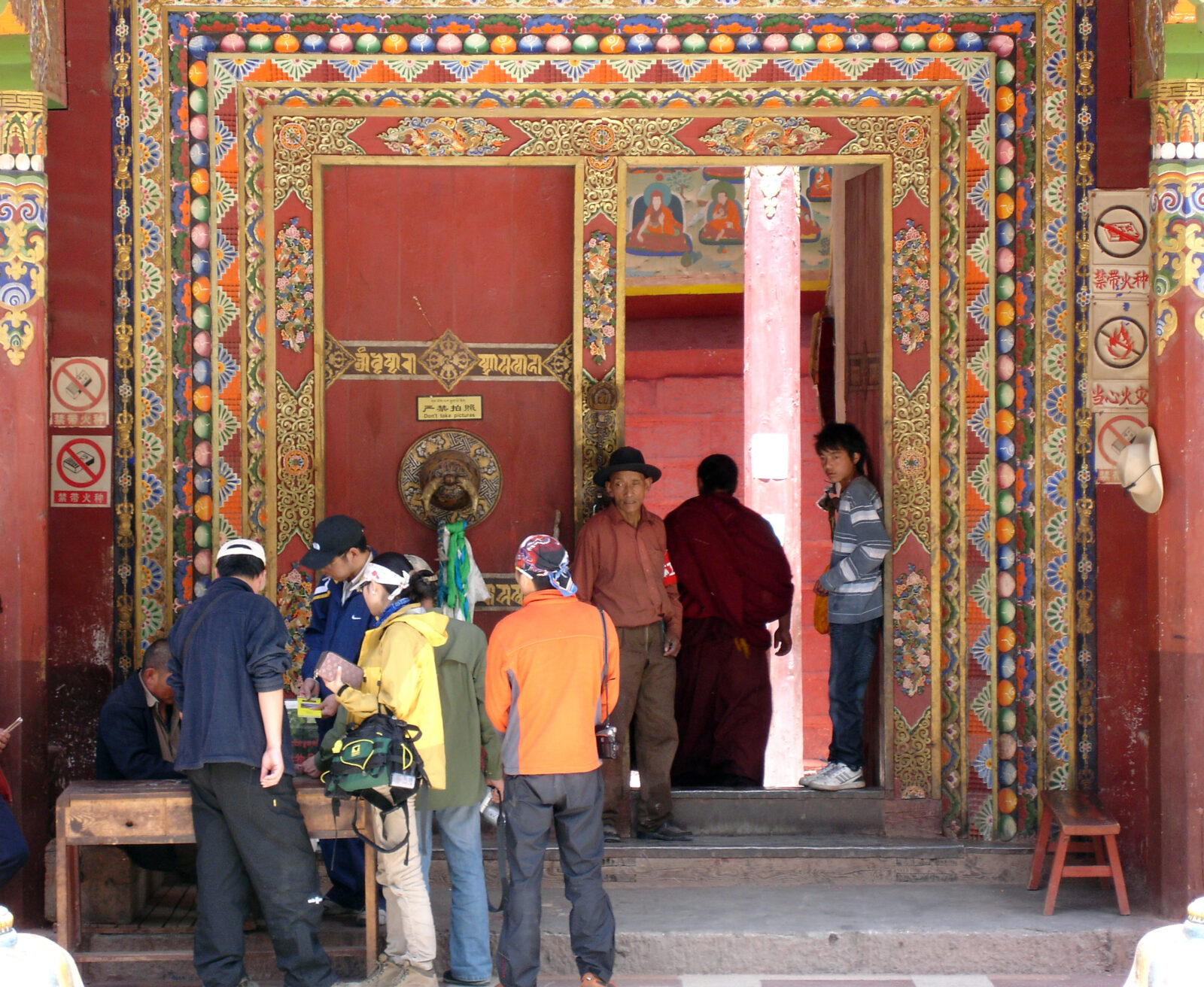

Main entrance to the Derge Parkhang; photo courtesy Dowdey/Meador/Padma’tsho

Nowadays pilgrims, scholars, tourists, and film crews regularly visit the renovated Parkhang and nearby Derge Medical School and clinic. They show their respect, walking kora in the morning with local people and monks, spinning prayer wheels, and prostrating themselves as they circle the building. When they go inside they are struck by the beauty of the 18th-century wall paintings in the two chapels, the rich decorations, the racks of thousands of blocks throughout the building, and the unique atmosphere of the main printing room, with prayer flags printed on brightly colored brocade hung all around, the rhythm of the printers at work, the sound of blocks knocking together and the occasional printer’s song rising over it all. I asked one of the managers of the Parkhang how he felt when he saw someone leaving with books or a print, and he told me, “I feel we have provided a service.”

It’s useful to ask the question of why woodcut books are still being produced by hand in the 21st century, why monks and lay people continue to use and treasure them when more efficient printing methods are available and, in fact, being used. I got the best answer at Dzogchen monastery where I visited a young tulku and his teacher in a tent and asked why they use woodcut books. The teacher gave us several good reasons. The tulku, though, simply raised a book over his head, smiled, and shook it. The gesture was as clear as it was simple—the woodcut editions are simply more holy.

A group of elders sitting with a printer across from the Derge Parkhang; photo courtesy Dowdey/Meador/Padma’tsho

For more on book production in Tibet, see Kurtis Schaeffer’s The Culture of the Book in Tibet.

Patrick Dowdey has conducted research in China and East Asia for over 35 years, first as a doctoral student in anthropology at UCLA and then as curator of the Mansfield Freeman Center Gallery (now part of the College of East Asian Studies) at Wesleyan University. Beginning in 2004 he led summer research projects on the Derge Parkhang in Ganzi Tibetan Autonomous Region of Sichuan with Clifton Meador of Appalachian State University and Padma’tsho of Southwest University of Nationalities in Chengdu. An exhibition of prints, books, videos, and photographs from that project was mounted in 2008 at Wesleyan and in 2009 at Columbia College Chicago. He is currently a visiting scholar at Wesleyan.

Get the latest news and stories from the Rubin, plus occasional information on how to support our work.