As part of the 2017 Sacred Spaces exhibition, the Rubin Museum partnered with Soundwalk Collective and Audio-Technica to present Khandroma: Himalayan Wind, an installation that uses sound to transport visitors to the Himalayas. Audio-Technica sat down with the Soundwalk Collective’s Production Director Simone Merli. Read on for a behind-the-scenes look at the recording process behind the ambitious project.

(This interview originally appeared on the Audio-Technica blog.)

Simone Merli: The Rubin’s curator Beth Citron has been following our work for a long time and wanted to commission us for a sound composition. She brought the Rubin curatorial team to our studio for a meeting, we spoke about our work and approach in the conceptualizing of an oeuvre, and listened to and watched our various productions in sound and film. We quickly came to the notion of wind, how its sound and singing patterns are especially evocative in the Himalayas, allowing sounds of prayers and chants to be echoed among the steep mountains, creating a natural musical body that resonates throughout a whole valley.

Knowing that the exhibition was commissioned for the fourth floor of the Museum, which houses the Tibetan Buddhist Shrine Room, we proposed the idea of recording wind at the highest located monasteries in the Himalayan chain, and portray an impressionistic and harmonic musical painting entitled Khandroma. The name comes from a deity and spiritual muse in Tibetan Buddhism, an energetic volatile being known as “”the one who traverses the sky.

Stephan Crasneanscki (Director) and Gabriele Giugni (DP), Niphu Gompa, Nepal.

The first step is lots of research, from a geographical, musical, and spiritual standpoint. We looked at various works that have been created around similar concepts, in every possible art form. We looked at photography, film, sculpture, literature; we listened to sound recordings from the region, musical compositions, orchestral works, and so on. This allowed us to start envisioning what kind of musical and filmic result we wanted to aim for.

From a practical point of view, the research on locations and territories is extensive; it can go on for months. We looked at all Buddhist monasteries in every country sharing the Himalayan chain, from Kashmir and the northwest tip of India, all the way southeast to the border of Myanmar, through Nepal, Tibet, Bhutan, and the various regions of India such as Sikkim, Himachal Pradesh, Arunachal Pradesh, and Uttarakhand; and finally landing with our attention to the ex-forbidden Kingdom of Lo, in Upper Mustang, Nepal. An exotic and completely preserved spiritual region of Tibetan descent into Nepal, that has the highest concentration of Buddhist monasteries at high elevation, above which are only the steepest and most unexplored Himalayan peaks.

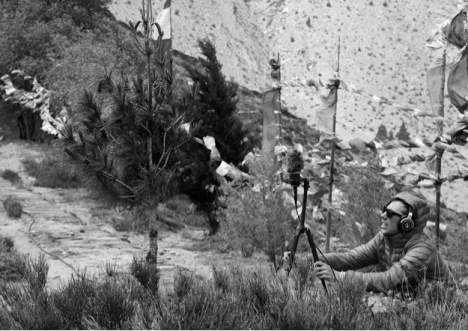

Stephan Crasneanscki (Director) and Paul Hance (DP), Syangboche La, Nepal.

Every day we would move to a different location and monastery, following the whims of the wind. We would travel to the next location early in the morning before the wind began to pick up, and by noon we would be recording. Every take is about 15 minutes long. We would set the microphones in one place and not move them. Our intent was to capture the tonal and textural variations that happen over the time, thanks to the continuously morphing and dynamic nature of the sound produced by the wind.

We used different capsules and we positioned them sometimes right against the wind, at times at an angle, depending on the kind of resonance we were aiming to record. Oftentimes the microphone was placed right against a surface: facing a hole between rocks, right against the opening of a metal pole holding prayer flags, high up by electricity cables swinging in the wind, up against a crack in the wall inside of an abandoned monastery, inside of a bell and so on. Our intention was to highlight the textures produced by the wind as it hits different surfaces, or to heighten the music tonality that exists within the wind sound.

Simone Merli, Chhussang, Nepal.

We brought a set of custom-made binaural microphones as well as three different Audio-Technica microphones and a Zaxcom Maxx mixer. Also it goes without saying, we used many different kinds of windjammers. Both the stereo couple of AT4050 placed in A-B position, and the AT4050ST have worked best for the wind field recordings. They did require thick wind jammers to best handle the power of the sound. They accurately portrayed the physical properties of the wind as well as the higher frequency textures, giving us a full bandwidth to work with while composing.

We would definitely like visitors to be surrounded by the sound and hopefully allow themselves to be transported to a calmer place.

Yes, complementing the audio experience, a video installation shows cyclic kaleidoscopic imagery of prayer wheels and flags from Himalayan monasteries, an effect created by handmade kaleidoscopes that are built with glass and crystals and then mounted on the camera lens. These glasses are the ones currently used by NASA for lenses of space observation telescopes. The resulting images formed inverted triangles, evoking a symbol in Tibetan Buddhism that represents the search for equilibrium and equanimity.

Capturing video was somehow similar in method as capturing the audio. We would film multiple shots of the same prayer wheel, varying each time the speed of the spinning of the wheel, and the amount of light that we would let into the lens, to create different variations and textures. We built four different kaleidoscopes with different mirrors and color filtered crystals that we would exchange in turn, depending on the image we were trying to capture, to see which one would best work with every color and pattern combination.

Rubin Museum

150 W. 17th St., NYC

Get the latest news and stories from the Rubin, plus occasional information on how to support our work.