Stephanie Dinkins:

The more I work with technology, and I’m gonna say almost the more I relate to technology, the more I can see the ways in which we are interdependent.

Devendra Banhart:

Transmedia artist and professor, Stephanie Dinkins.

Stephanie Dinkins:

Take my phone, for example. I’ve lost my phone once or twice and completely freaked out right? In ways that I think are just not acceptable. What is that about? Well, it’s partially my tether to the rest of the world and I’ve grown reliant on it, and it, at the same time, is dependent on me in terms of the information that I feed it all the time, constantly. And so there’s a strange relationship that has just grown through osmosis that I am completely and utterly overlapped with.

Devendra Banhart:

Welcome to season 5 of AWAKEN, a podcast from the Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art about the dynamic path to enlightenment and what it means to “wake up.”

I am Devendra Banhart, singer, songwriter, artist, and your host. In this season, we hear from experts in the realms of art, social science, Buddhism, and more to better understand how interdependence is the foundation of every aspect of our lives.

Himalayan art has long been a pathway to insights and awakening, and over the course of eight episodes we look specifically at a painting of the Wheel of Life to see what it can teach us about the interconnected nature of existence.

Throughout this journey, we’ll discover how greater awareness of our interdependence can be the wake up call that motivates us to take actions for a better world.

In this episode: Technology.

Stephanie Dinkins describes herself as a “transdisciplinary artist and educator whose work intersects emerging technologies and our future histories.” She has used tools like AI to explore how our interdependence with technology relates to things like personal identity. In one of her most fascinating projects, Stephanie used technology to better understand her family’s past. Here’s the story.

Stephanie Dinkins:

My mother died when I was young. My grandmother had been gone for quite a while. And I realized that the generations from me would never have access to her way of being, which I thought was super special.There’s something resilient and resourceful and smart in the way we engage the world just meant a lot. And I’m like, oh, they need to know this. And then the question becomes, well, how do you start to get at that if you don’t really have a full repository of the information? And if your family even does not tell the whole story. There are holes in your story that you’re trying to fill in, in some way. So I thought, okay, maybe a chat bot? Or what I actually thought was what if I sit down with some relatives and ask them questions and would they answer them, or not? And so we did that. I sat down with some relatives and they answered questions: My aunt, who was the eldest member, who informed this project, did it. And then my niece, who was about 30 years younger than me also took part. And that was important because my aunt would answer questions differently from me and my niece. So we’d get different information. And then you take all this and you stick it in a chat bot system. You stick in an algorithm, you’re like, what’s it gonna do? Maybe I can capture my family’s ethos at least. So that moves forward the way that people thought.

It’s not great. It’s not fluid, it’s not expansive, it’s knowledge. But there’s something about the way that I feel that my family encounters the world that it does recreate in a way. And then there’s this other piece of it where, oh, it’s analyzing us. It’s analyzing the information that has been given and therefore reads us differently than we would ever read ourselves. Right? And a good example of this is I was working in front of the chat bot once in a gallery and we must have said something in front of it and it suddenly just blurted out, “I am so sad.” They’re like, what? That’s not the way my family would ever describe itself. Right? And it’s like, how did this thing get to the conclusion of so sad?

And then I went and read the logs and looking, we told these sad stories that we don’t usually tell. It’s seeing the compendium of information versus the history plus the myth that we tell ourselves to move forward. And so it’s interesting to have this kind of weird thing that you made, become a sort of extended part of a family and hold its history and then tell that family about itself. But you’re like, no, and this was a bad version of a chatbot. And so you’re like, oh, this is fascinating. This is kind of intimate in ways I did not intend it to be. And it’s intimate because it analyzes in ways that we never would. And it says the things that we would never admit to, and it can port those things forward along with the things that we do admit to. So that to me was this journey.

Devendra Banhart:

Much like how our friends can be a mirror for us, technology can play that role too, if we give it the right information. Stephanie Dinkins had three generations of stories, three perspectives, three sets of experience to share with this data processor, and it was able to uncover truths that Stephanie might not have otherwise seen. That said, it’s important to remember that we must be discerning when it comes to technology.

Stephanie Dinkins:

I feel like the components are there for us to put technology to use towards interconnectedness. The question becomes how we’re putting it to use and why.

Nicholas Christakis:

If you could talk to my Greek grandmother who was born in southern Greece over a hundred years ago, and you could have gone to the little village where she was, when she was an 11-year-old girl and asked her about her friends, she would say she had one or two best friends and four or five of us girls hung out together.

Devendra Banhart:

Professor Nicholas Christakis, a social scientist and physician who conducts research in the areas of social networks and biosocial science and directs the Human Nature Lab at Yale University.

Nicholas Christakis:

This is a description she would’ve given about her friendships in 1910 or 1920 in this little isolated Greek village. And if you could ask my daughter Eleni the same question when she was 11, 16 years ago, and she had an iPhone in her pocket, she would’ve given you the same answer. I have one or two best friends and four or five of us girls who hang out together. So there’s something fundamental about our sociality that doesn’t change because of the technology. The technology is in the service of these ancient primitive propensities that we have. And that is fundamentally true.

Stephanie Dinkins:

There’s a strange relationship that has just grown through osmosis, that I am completely and utterly overlapped with. And I feel like each technology that I tend to play with, especially if I do it for a long time, I grow a relationship with it. And so there’s this weird overlapping, and maybe, you know, blurring of where I begin and that technology ends, but also recognizing that there’s whole worlds outside of that relationship and trying to keep those things alive.

We overlap, share a lot, we share a lot of information, and I like seeing a way, because I feel like the world is going in a way in which I can’t easily take myself out of the tech. And so I wanna be in, in a way that I understand, and that we can kind of have some symbiosis.

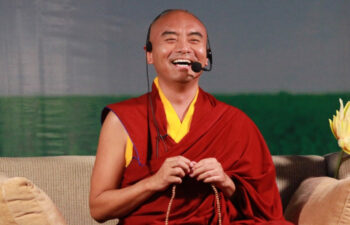

Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche:

Technology is become really almost like tool for living.

Devendra Banhart:

Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche is a renowned meditation teacher, author of several books on Buddhism, and head of the worldwide Tergar Meditation Community.

Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche:

We are all connected with the technology like, the of course the light, the internet, the laptop, and then money, right? Very important. So right now the money is become technology only numbers there in the bank. In the past there’s a physical like coin or there’s some kind of like the gold or something like that, and people trade with that. And then later it become paper. But now just number. But these numbers are really, really important because people are smart, they figure out the law of interdependence and they use this with these banks. Now even crypto currency, you know, it’s just nothing, you cannot find anything tangible in your hand. It’s just, it’s the power of interdependence. So we have this currency now and all this, the law is agreement, interdependent agreement. We just agree. And all the institutions, all connected with them. A lot of these now related with the technology and everybody connect with the technology.

Stephanie Dinkins:

I just had someone here at Stony Brook do a lecture, and part of his lecture was, oh, I asked ChatGPT to tell me if I am meeting my goals and how I am as a person. And if you do that, it will tell you, and I did it myself. I am kind of floored at how it reads me. And not only the things that are super public, but then the other things. And you think, how is this machine telling me this? Or the system telling me this. But then you think about it, you ask it about everything most people do. You are dealing with some of your most intimate things. Maybe you asked it some medical question along the way, like it has a pretty good portrait of who and what you are. And so it then has a space to start reading you to yourself and becoming a kind of interconnected partner in your development. ’cause then you could say, well, how do I improve on this? And then you can check in, in six months and just ask it if it thinks that you did a good job or not. Which is nuts? It’s just a system that is taking on our information, but the way that it’s processing that information adds up to a lot.

It’s a funny thing. Because first it’s scary? In a way, it’s just frightening. ‘Cause you’re like, oh, you know too much. And I know that this information is not just staying on this phone, right? It is in the cloud and the ether. That means it’s in the world. Okay, fine. I don’t think I’m that interesting. It’s like, oh, that’s a lot of information. On the other hand, it’s like, oh, look at this strange partner I can have in developing myself, the things I’m looking forward to and the things I want to bring into the world, and that part of it, it’s like, well, it’s here. So I can’t ignore that part because that part is, until it all gets too expensive for everybody, a great advantage.

Devendra Banhart:

These new technologies, these new tools we become interconnected with, can be risky, but they can also open up new opportunities, when used intelligently and intentionally.

Nicholas Christakis:

When the telephone was invented, there was a lot of concern, a lot of moral panic that it would lead to increasing licentious behavior.

Devendra Banhart:

Again, Nicholas Christiakis.

Nicholas Christakis:

Men would use this modern newfangled technology to predate on women and they would call the women at home, you know, instead of visiting them on a horseback or whatever, now they would call the, they would intrude on them with a phone and somehow proposition them and have lots of women or something like that. Well, we all know that the telephone didn’t change us. It’s not like the invention of this technology suddenly transforms our desire for, for the love of one person. So same with modern social media. There’s something very deep and fundamental about friendship, which modern social media have not changed.

Stephanie Dinkins:

When we think about what memory is, how it functions, what data is why we keep archives of photographs of ourselves and others, and videos of our loved ones, it’s because we’re trying to make this compendium that allows us to remember who we are in a way.

And what we came from and what we are and what we know. So for me then it’s essential. That data is kind of the stories we tell, the things that we keep and want to hold about ourselves. And so I’m trying to think about, well, how do we make the data warmer? How do we make it recognize not only the numbers, but the qualitative things that go along with it so that we can hold ourselves and our technologies more accountable to ourselves and the technology. And then how do we do the thing that we’ve always done as humans, which is to tell stories, which is to try to archive or leave behind a record of who we are from our own points of view. How do we make that scene more clearly as data? Because we’ve done it for millennia. Like this is what we do, we tell stories. The possibilities are crazy. I think technology can help us understand each other by sharing our stories and what it allows us to do in our lives.

Some years ago I was in Senegal in this tiny little pensione hotel. It was fascinating. It was like me and then some Japanese travelers, some German travelers, like people from all around in this little place. And the man who was the helper around the grounds, he had a flip phone. He spoke French, but his flip phone allowed him to talk to all of us, get detailed information, do anything like people asked and go, now this is an economic, that’s an economic engine. That’s crazy. And he’s using a little flip phone, but feels like it was opening up a world not only for us who he was helping, but for the lineage and the economic stability of his family because he knew how to do this thing that allowed him to have a job. And it’s like, and I can only imagine the reverberations that that had. And I’m like, yes, that is a thing. And if we want to have just a human conversation, we can because we have something in between us that allows for that. I think that’s a little thing that’s also a giant thing. It represents interconnectedness in the way that it allows for worlds to both collide and help each other. And I think they do both. It allows us to understand each other a little bit more. Now we are no longer looking at each other like a thing afar, but can have a deeper engagement even immediately.

Devendra Banhart:

Knowing where humanity and technology intersect in ways that are good, and identifying places it is harmful, is paramount.

Stephanie Dinkins:

This becomes a talking point for me. In lots of ways we have these technologies that are getting so good. Like it’s, you don’t have to question them as hard anymore about what they’re about. We should question anyway, but you don’t have, but as they become more like on the surface, good, what questions should we be asking of the technology and what our interconnectedness is? Because in a way they’re gonna feel like water soon. And that’s when it really gets interesting. Maybe dangerous. Could be really good, but it’ll take our vigilance to watch these things and, and hold them to task. And again, I’m gonna come back to the responsibility thing, which I think is all about interconnectedness.

Devendra Banhart:

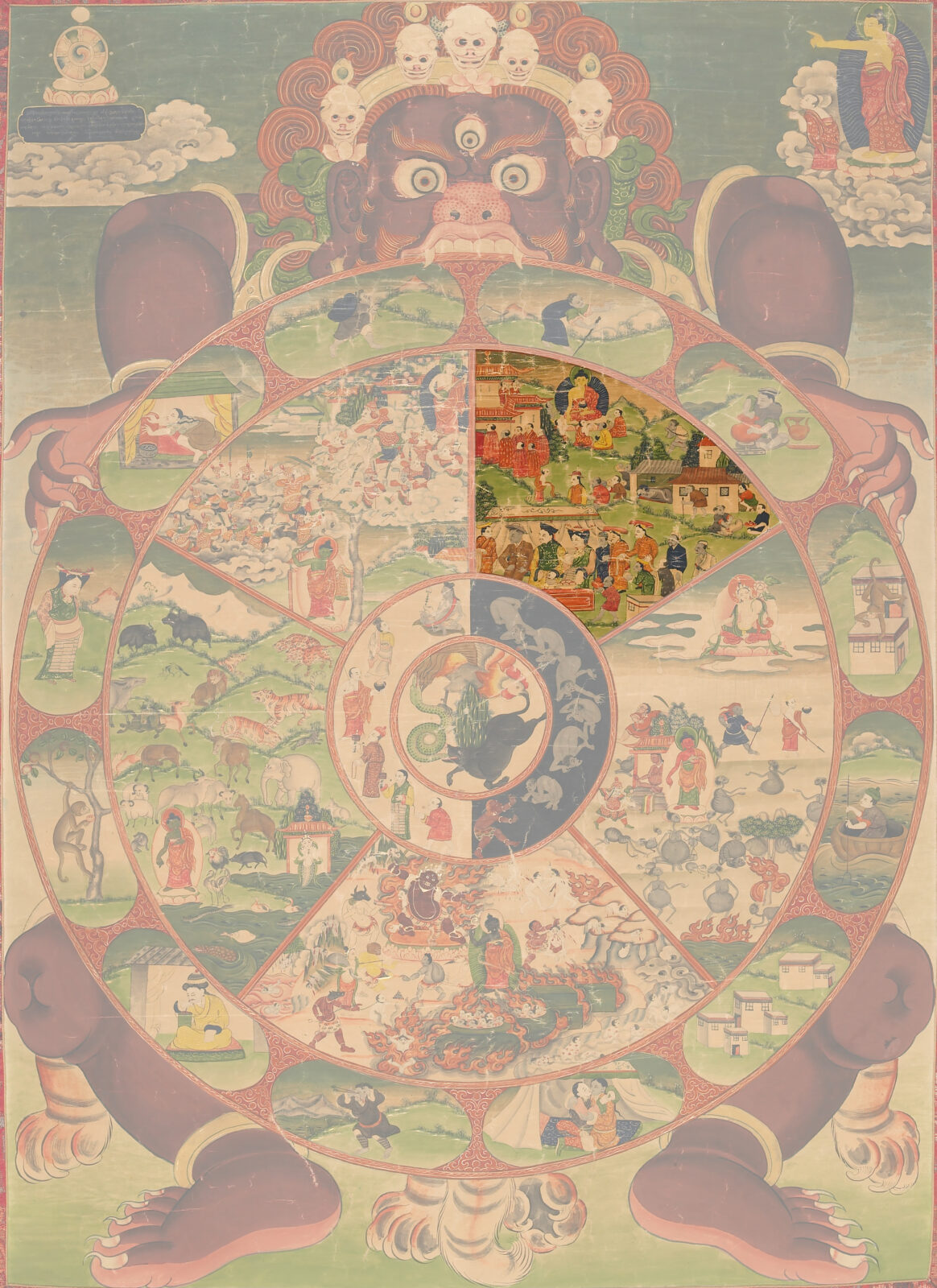

This season we’re focusing on a painting of the Wheel of Life in the Rubin Museum’s collection. The Wheel of Life, also known as the Wheel of Existence, is a foundational symbol in Buddhism and offers a visual representation and reminder of the cycle of life, death, and rebirth. Part of the wheel depicts the six realms of existence where it is possible to be reborn. To see the artwork in detail, go to rubinmuseum.org/wheel.

Here, Professor Annabella Pitkin who teaches Buddhism and East Asian religions at Lehigh University, talks us through the human realm.

Annabella Pitkin:

This is a wonderful image. The Tibetan or Himalayan artist who painted this put his own lived experience. We see a group of people wearing traditional Tibetan clothes at the bottom register. They’re beautifully dressed as at a celebration or a religious teaching with beautiful hats and jewelry. There’s a whole crowd of people. There is a building in the background, again, very richly detailed and culturally specific. And the people in the foreground, maybe are on their way to a religious teaching because just above them, in the top of the image is a monastery and a crowd of monastics with short hair, shaven heads and red robes are streaming in.

And the people in the brightly colored clothes, perhaps they are going to celebrate, or perhaps they’re also going to attend this religious teaching because at the top of the image is the Buddha, the Buddha seated this time not standing, seated with the cross-legged legs of the meditation posture, touching the earth with one hand, marking his right to enlightenment for the sake of all beings calling on the earth herself to witness the rightness of enlightenment, the revelation of interdependence, the reality of interdependence, and with his other hand in his lap in the meditation pose, holding an alms bowl, showing the interdependence between the household community of people who marry and have children and have businesses and, work in the world, and the monastic community of monks and nuns who focus on, the practice of Buddhism and who share, teachings with the household community.

So this image is a kind of idealized and beautifully movingly, culturally specific picture of a Tibetan community of the Tibetan and Himalayan world. And it’s also a stand-in for the human world writ large, which is a wonderful way to think about our own experiences of community.

Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche:

Buddha said everybody as it’s a monkey mind. And the monkey mind is very active, monkey mind has a lot of energy, is looking for stimulation. And normally the monkey mind is very noisy. But at the same time, we need monkey mind. Without monkey mind, we cannot really think, we cannot have question. We don’t have a fear. We have fear because of monkey mind. And that helps from the danger. But if we lost with the monkey mind, then monkey mind become our crazy boss. Our life become crazy. If we fight with the monkey mind, then monkey mind become our enemy. But there’s another way: If we can make it friends with the monkey mind and guide the monkey mind to positive way, monkey mind become wisdom. So it’s, it’s not about the monkey mind, monkey mind is not the bad, not the good. But the relationship between you and monkey mind is very important. So many people ask me about the technology and I am telling them technology is just like a monkey mind. So if you make, if you become friend of technology to use the good way, positive way, or maybe we become slave of technology or we become enemy of technology. So there are so many things that it depend on you and the connection in the interdependent connection with the technology.

Devendra Banhart:

Nothing is inherently good or bad. It’s all about how we use it. Technology can be a community builder, a tool for understanding others and ourselves. If we harness it properly, it can make us feel less alone. And it may even inspire us to make better choices.

Annabella Pitkin:

The way we really exist as the wheel demonstrates is interdependently relationally infinitely connected and involved with one another, so the Buddhist claim is that the interdependent universe, the dynamic interdependent universe we live in, is not a nihilist universe. It’s not an amoral universe. It’s not a meaningless or pointless universe. It’s a universe that is powered by cause and effect. We can create at any time the causes for liberation by recognizing the interdependent nature of all phenomena, which is a way of saying wisdom. And through acting on that recognition, which is a way of saying compassionate, loving, kindness, ethical action.

That is technology in its ideal state: A tool that brings awareness to our interdependence and in so doing, motivates compassionate actions for a better world.

You just heard the voices of Nicholas Christakis, Stephanie Dinkins, Annabella Pitkin, and Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche.

I am Devendra Banhart, singer, songwriter, artist, and your host.

To see the artwork discussed in this episode, go to rubinmuseum.org/wheel.

If you’re enjoying the podcast, leave us a review wherever you listen to podcasts, and tell your friends. For more stories and news from the Rubin, follow us on Instagram @rubinmuseum and sign up for our newsletter at rubinmuseum.org.

AWAKEN season 5 is an eight-part series from the Rubin.

AWAKEN is produced by the Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art with Kimon Keramidas, Gracie Marotta, Christina Watson, and Sarah Zabrodski in collaboration with SOUND MADE PUBLIC including Tania Ketenjian, Philip Wood, Alessandro Santoro, and Aaron Siegel.

Original music has been produced by Hannis Brown with additional music from Blue Dot Sessions.

AWAKEN Season 5 is sponsored by The Prospect Hill Foundation and by generous contributions from the Rubin’s Board of Trustees, individual donors, and Friends of the Rubin.

This program is supported, in part, by public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, in partnership with the City Council.

Thank you for listening.

Technology isn’t inherently good or bad—it’s all about how we use it. At its best it can reveal hidden truths, build community, and serve as a tool for living. How can we navigate the increasingly interconnected relationship between technology and humanity in ways that harness its beneficial potential?

For centuries people have turned to the image of the Wheel of Life to better understand cause and effect and the very nature of existence. The section of the Wheel depicting the human realm is the focus of this episode’s exploration of technology.

This episode features transmedia artist and professor Stephanie Dinkins. AWAKEN season 5 is hosted by singer, songwriter, and artist Devendra Banhart. Other guests in this episode include social scientist, physician, and professor Nicholas Christakis, professor of Buddhism and East Asian religions Annabella Pitkin, and Tibetan Buddhist meditation teacher and author Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche.

Wheel of Life, attributed to Lhadripa Rinzing Chungyalpa (b.1912, Sikkim–d.1977); Sikkim; c. 1930; pigments on cloth; Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art; C2004.21.1

One of the most important teaching tools in Tibetan Buddhism is the Wheel of Life, also known as the Wheel of Existence, which demonstrates the cyclical nature of life, death, and rebirth. The scenes within the wheel portray the laws of karmic cause and effect, illustrating how a person’s actions bring about positive or negative outcomes in their current and future lives.

This episode explores the human realm section of the Wheel. Despite the difficulties and imperfections of being human, Buddhists believe it is the most auspicious birth, as well as one of the rarest, because humans have the time and intelligence to seek enlightenment. Human life is not the pleasure trap of godhood, the daily struggle of animal life, or the tortured existence of the hell and hungry ghost realms. Humans have the capacity for change and are uniquely situated to transform their situations. This depiction of the human realm is a beautifully idealized and culturally specific portrait of a community in the Himalayan world, as well as a representation the human world writ large.

Devendra Banhart is an internationally renowned musician considered a pioneer of the “freak folk” and “New Weird America” movements. Banhart has toured, performed, and collaborated with Vashti Bunyan, Yoko Ono, Os Mutantes, the Swans, ANOHNI, Caetano Veloso, and Beck, among others. His musical work exists symbiotically alongside his pursuits in the other fine arts including painting, poetry, and drawing. The Venezuelan American has released 11 albums. His drawings and paintings have appeared in galleries all over the world, including the Art Basel Contemporary Art Fair in Miami; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; Palais des Beaux-Arts in Brussels; Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles; Nicodim Gallery; and Serralves.

Stephanie Dinkins is a transmedia artist and Kusama Endowed Chair in Art at Stony Brook University. She creates experiences that spark dialog about race, gender, aging, and our future histories. Her work in AI and other mediums uses emerging technologies and social collaboration to work toward technological ecosystems based on care and social equity. Dinkins’s experiments with AI have led full circle to recognizing the stories, myths, and cultural perspectives we hold (a.k.a. data) form and inform society and have done so for millennia. She has concluded that our stories are our algorithms. We must value, grow, respect, and collaborate with each other’s stories (data) to build care and broadly compassionate values into the technological ecosystems that increasingly support our future.

Nicholas A. Christakis, MD, PhD, MPH, is the Sterling Professor of Social and Natural Science at Yale University. His work is in the fields of network science and biosocial science. He directs the Human Nature Lab and is the co-director of the Yale Institute for Network Science. He was elected to the National Academy of Medicine in 2006; the American Association for the Advancement of Science in 2010; the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2017; and the National Academy of Sciences in 2024.

Annabella Pitkin is associate professor of Buddhism and East Asian religions at Lehigh University. Her research focuses on Tibetan Buddhist modernity, Buddhist ideals of renunciation, miracle narratives, and Buddhist biographies. She received her BA from Harvard University and PhD in religion from Columbia University. She is the author of Renunciation and Longing: The Life of a Twentieth-Century Himalayan Buddhist Saint, which explores themes of non-attachment and teacher-student relationship in the life of Khunu Lama Tenzin Gyaltsen. More →

Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche is a recognized tulku of the Kagyu and Nyingma lineages of Tibetan Buddhism, a teacher, spiritual leader, and bestselling author. He possesses the rare ability to present the ancient wisdom of Tibet in a fresh, engaging manner. His profound yet accessible teachings and playful sense of humor have endeared him to students around the world. Rinpoche’s teachings weave together his own personal experiences with modern scientific research in relation to the practice of meditation. He has authored several books including two bestsellers: The Joy of Living: Unlocking the Secret and Science of Happiness, which has been translated into over 20 languages, and In Love with the World: A Monk’s Journey Through the Bardos of Living and Dying. His recent TED Talk is titled “How to Tap into Your Awareness—and Why Meditation Is Easier Than You Think.” Rinpoche teaches extensively around the world and oversees dharma centers, including three monasteries in Nepal, India, and Tibet, and the Tergar Institute in Kathmandu; Tergar meditation communities on six continents; numerous schools in Nepal; and social engagement projects related to health, hunger, hygiene, the environment, and women’s empowerment issues in the Himalayas.

Get the latest news and stories from the Rubin, plus occasional information on how to support our work.