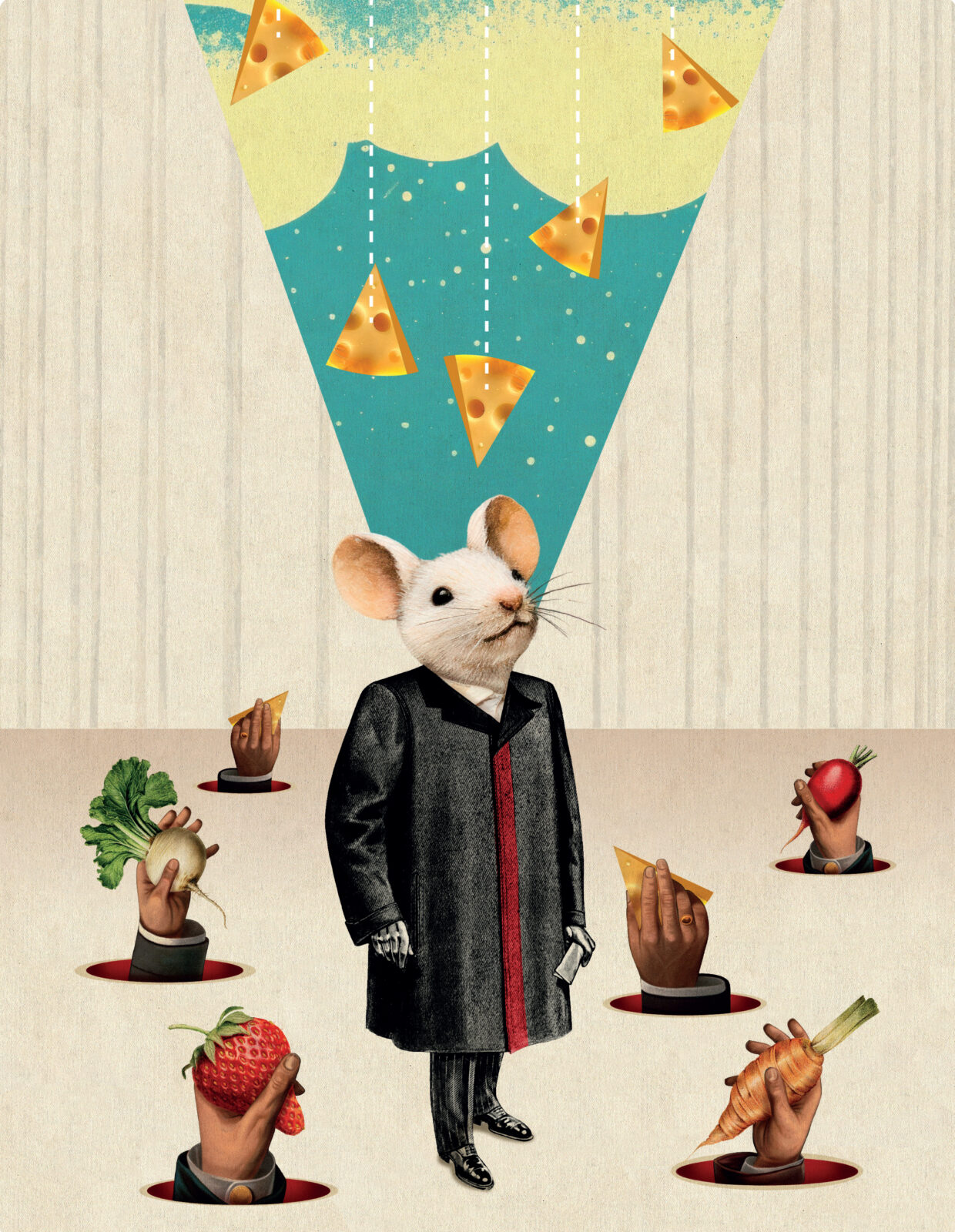

Illustration by Beto Val

Illustration by Beto Val

Where does the world end and I begin? From the moment of conception, our porous membranes allow the flow of information, in all its forms, from outside in and inside out. This reciprocal exchange of information is how energy gives rise to form.

As roots of germinating seeds are beckoned by gravity and sprouts shoot skyward to lean toward the light, such tropisms also exist for us, directing the trajectory of development throughout our lives, fine-tuning and changing our course as circumstances demand. The success of life lies in the tension between plasticity and stability. We must adapt to our environment yet also maintain habits of thinking and behavior. Habits harness the most efficient electrochemical path to achieve our goals. How exhausting would it be to acquire skills and knowledge repeatedly from scratch, learning them over and over, and how limiting for learning not to be lifelong?

Studies observing the amnesiac patient H. M.1 lead to broad taxonomic distinctions of memory: explicit and implicit. Explicit memory—the stuff you can talk about—was further divided into semantic memory (knowledge about the world) and episodic memory (knowledge about what happened).2 Semantic and episodic memories form the narrative of self. They tell us who we are

Without them we would be nobody, yet we are forming new ones all the time.

H.M., who had his temporal lobes removed to treat his epilepsy, could not form new explicit memories. He could not tell you what he had had for lunch, but he could form implicit memories. He improved at tasks that require fine motor skills despite not recollecting having done the task before. The conditions of our environment, the smallest tasks of our day, form us over time, without us realizing.

We now know that plasticity and neurogenesis continue throughout life.

Until embarrassingly recently, neurogenesis was thought to occur only during development, but aren’t we always developing? We now know that plasticity and neurogenesis continue throughout life. We are not autonomous blueprints dividing immune to input. Our development is, in fact, a continuous feedback loop of constant refinement in response to our internal and external milieux. There are, however, specific developmental windows of intense plasticity, known as critical periods, when interactions between the developing organism and the world it inhabits are particularly crucial. This particular brain develops to perceive this particular world, with this particular body.

A striking example of the biological co-authorship between the internal and external environments is the necessity of visible light for the development of the visual system. David Hubel and Torsten Wiesel received the Nobel Prize in 1981 for experiments performed years earlier to better understand vision, unfortunately using kittens. At birth, kittens possess the necessary neuronal apparatus for sight, but if the eye is deprived of light by being sutured shut, the kittens lose perception of light through the sutured eye permanently, even when the suture is removed.3

Interestingly, the neuronal atrophy, due to the light deprivation, occurs in the brain at the level of the cortex, not the eye. If the suturing is performed in an adult cat, once the visual system has developed, input from that eye will retain its potency. As long as light from the outside is received at the correct point in time, the necessary cascade of proliferation and pruning occurs that provides a stable pathway for sight. If the suturing occurs beyond this time, beyond the critical period, once the circuitry has been formed, glazed, and cured, light remains perceivable through the eye, despite its momentary absence in adulthood.

It is not only the absolute presence of input that matters but also the quality. Rats raised in a simple cage have far fewer connections between neurons in a layer of their cortex than rats raised in “enriched” environments4 that contain toys and materials of multiple textures. Reciprocally, the brain changes its connectivity during periods of intense creativity that impact an organism’s environment such as nest building and tool making.5

I work in a lab that studies appetite. Fasting a mouse is probably the most powerful way to motivate them to eat. Mice, born in a lab, are nourished by their mothers for the first three weeks and then weaned into independent life where they typically receive food pellets through a metal grid situated above them. Last year, inexperienced as I was in behavioral experiments, I expected that if I fasted a mouse and the next day placed food pellets on the floor of their cage, they would eat the pellets.

To my astonishment, the mice, even in their highly motivated, fasted state, ignored the food, moved past the food, stepped over the food. How could this be? When the food was presented they reached for the sky. Then it dawned on me—for their entire existence, food had only arrived from the sky. In their world, that is where food came from. They could smell the food when I placed it in the cage, but because it didn’t come from the sky, they couldn’t recognize it as food, even though their lives depended on it. It took a few trials and innate curiosity for them to realize that nourishment could also be found on the ground.

The image of the mice reaching for a foodless sky haunts me frequently. What opportunities am I refusing to see? What is being presented to me in a way that I do not expect or recognize? How has the world I have grown up with hindered my ability to see things as they are? What nourishment is hiding in plain sight? It has been proposed that psychedelics “re-open” closed critical periods enabling us to undergo intense plasticity.6 Our experience in the world shapes the way we see it, and it takes courage, curiosity, and awareness of this to dare to see things differently and sensitize ourselves to a stimulus we may have never encountered before.

1. B. Milner, “Les troubles de la mémoire accompagnant des lésions hippocampiques bilatérales,” in Physiologie de l’hippocampe (Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, 1962), 257–272. English translation by B. Milner and S. Glickman, eds. (Van Nostrand, 1965), 97–111.

2. Larry R. Squire, “Memory Systems of the Brain: A Brief History and Current Perspective,” Neurobiology of Learning and Memory 82, no. 3 (2004).

3. D. H. Hubel and T. N. Wiesel, “The Period of Susceptibility to the Physiological Effects of Unilateral Eye Closure in Kittens,” Journal of Physiology 206 (1970): 419–436.

4. B. B. Johansson and P. V. Belichenko, “Neuronal Plasticity and Dendritic Spines: Effect of Environmental Enrichment on Intact and Postischemic Rat Brain,” Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism 22, no. 1 (2002): 89–96.

5. T. Topilko, S. L. Diaz, C. M. Pacheco, F. Verny, C. V. Rousseau, C. Kirst, C. Deleuze, P. Gaspar, N. Renier, “Edinger-Westphal Peptidergic Neurons Enable Maternal Preparatory Nesting,” Neuron 110, no. 8 (2022): 1385–99.

6. R. Nardou, E. Sawyer, Y. J. Song, et al. “Psychedelics Reopen the Social Reward Learning Critical Period,” Nature 618 (2023): 790–798, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06204-3.

Leah Kelly is a neuroscientist at Rockefeller University. She uses electrophysiology, tracing, and imaging to elucidate how neurons communicate with the rest of the body to regulate appetite and metabolism. In 2014 she cocurated the Impakt Festival in the Netherlands. Her essay “Sense of Self” appears in Experience: Culture, Cognition, and the Common Sense, published by MIT in 2016.

Beto Val creates collages that immerse viewers in a surreal yet somehow familiar world full of absurd and eccentric beings. His passion is exploration and play in all its expressions. See his digital work at elbetoval.com and @elbetoval.

Get the latest news and stories from the Rubin, plus occasional information on how to support our work.