Pamela Ayo Yetunde:

When I think about interdependence, I think about when I was taking a walk with friends in Zimbabwe when I was right out of college.

Devendra Banhart:

Pastoral counselor, teacher, and author, Pamela Ayo Yetunde.

Pamela Ayo Yetunde:

And we encountered some Zimbabweans. And we said, hello, how are you? And then they said, we are well, if you are well. And that was the first time I had a feeling of connection with complete strangers in a way that inspired me to go deeper into that way of understanding our connections with each other and our commitments.

Interdependence tells Buddhists that your happiness is my happiness.

Devendra Banhart:

Professor Annabella Pitkin teaches Buddhism and East Asian religions at Lehigh University.

That in a very kind of fundamental way, it’s not really possible for me to be completely happy if you are suffering. And that relationality then gives rise to all the forms of ethical behavior and loving kindness. But it’s not a sort of question of forcing oneself to do the right thing. It’s reframed in this language of interdependence as being a more realistic way to engage with the world around us. Realistically, we are all in it together.

Devendra Banhart:

Welcome to season 5 of AWAKEN, a podcast from the Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art about the dynamic path to enlightenment and what it means to “wake up.”

I am Devendra Banhart, singer, songwriter, artist, and your host. In this season, we hear from experts in the realms of art, social science, Buddhism, and more to better understand how interdependence is the foundation of every aspect of our lives.

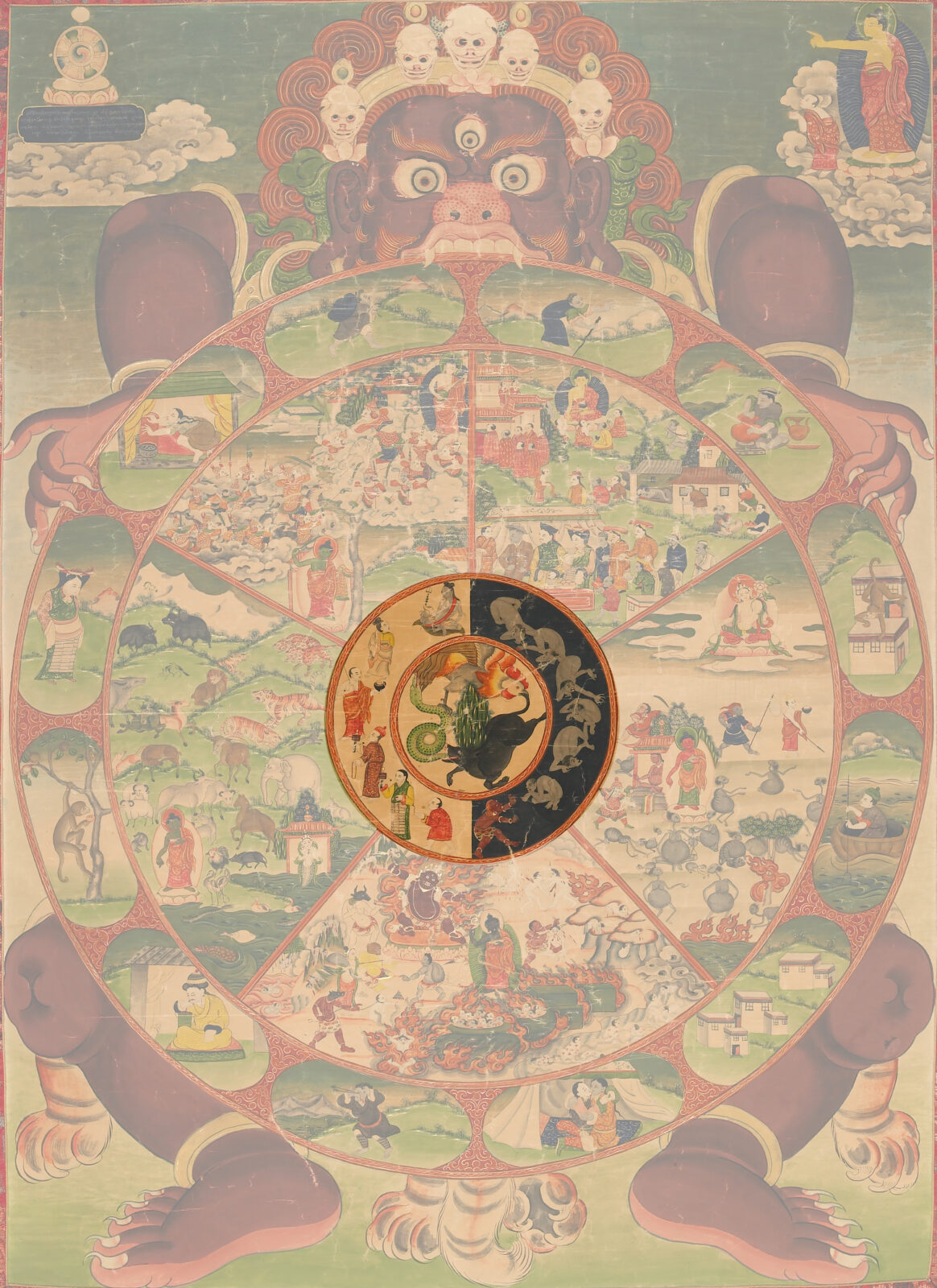

Himalayan art has long been a pathway to insights and awakening, and over the course of eight episodes we look specifically at a painting of the Wheel of Life to see what it can teach us about the interconnected nature of existence.

Throughout this journey, we’ll discover how greater awareness of our interdependence can be the wake up call that motivates us to take actions for a better world.

In this final episode, we are exploring how to integrate what we’ve learned about interdependence over the course of this season into our lives. How can we put some of the teachings embedded in the Wheel of Life into practice?

Again, Pamela Ayo Yetunde.

Pamela Ayo Yetunde:

I was told by friends in Indiana when I was in law school, oh, you’re moving to San Francisco. You must go to Glide. I grew up in the United Methodist Church. No, no. You must promise me you’ll go there. So I did. And I remember being overwhelmed actually, by the number of people in the sanctuary. So many people. And at that time, the relationship with my mother was extremely difficult. She was not talking to me. We had been very close. So I was feeling a lot of, a lot of things, some shame, anger, guilt, you name it.

So when I walked into the sanctuary, I sat as far back from the pulpit as I could, because I did not want to connect. I didn’t want anyone to know I was there. I didn’t wanna open up about where I was in my life. I cried. I cried. The music was so wonderful. I cried, cried, cried. And then I’d leave, and then I’d go back and I inched my way towards the middle. And when I got to the middle, that’s when I began to feel this nonjudgmental culture that supports the feeling of interdependence. It doesn’t matter what you’ve done in your past, what matters is what you want to do now and with whom. And we are here to support you. Yes, complete strangers from all walks of life, from homeless people to very wealthy people born in the states from other countries. We are here together to support each other’s recovery because we’re all recovering from something.

Annabella Pitkin:

We are all connected all the time, and we always have been.

Devendra Banhart:

Annabella Pitkin.

Annabella Pitkin:

And that connection is dynamic. It’s always changing. It’s not necessarily gonna feel the same at every moment, but the connection between all of us is always there. It’s a basic fact like light or gravity or mass. It’s a fundamental fact of the universe. And so our ethical practice and our psychological and emotional experiences of connection and love and loving kindness and care for one another, that’s a kind of engagement with something real, something that’s part of the reality all around us.

Pamela Ayo Yetunde:

Interdependence makes me think about non-separation. What does that mean? In the United States, we have a history of apartheid. We are still working with the vestiges of apartheid. So what does it mean to think of each other as belonging to one another? Being a part of one another, that my wellbeing truly is dependent on yours, and yours are mine. And if we can grasp that and live into that, then how might we can enjoy each other, and and be in solidarity with one another. When things get tough, all these things bubble up.

It looks like, in part, stepping away from concentrating on ourselves so much. Well, we are not the only person, that is in need. It looks like sharing, it looks like curiosity, it requires listening to others deeply in this, deeply listening, what I call, listening upward, listening so deeply that someone wants to tell you their story. And then when we hear that story, we are changed and we wanna be changed by it. That being changed then translates into a different kind of behavior and posture towards those we are listening to. And so we are making each other, sometimes people call this intersubjectivity. We go from being objects to one another, to being engaged in the intersubjectivity of one another, where we are making each other whole. I think it’s a beautiful thing also that should translate, I think, into not being afraid of each other as much as we are these days. Right. That I can see in you, a colleague, a comrade, even a relative, and a family member.

Nicholas Christakis:

There were some scholars at MIT who were studying the brains of Buddhist monks.

Devendra Banhart:

Professor Nicholas Christakis is a social scientist and physician who conducts research in the areas of social networks and biosocial science. He directs the Human Nature Lab at Yale University.

Nicholas Christakis:

And they were scanning Buddhist monks, their brains compared to, let’s say, normal human’s brains. And there was an interview being done by the scientist, and they were also interviewing some of the Buddhist monks. And they interviewed this monk and they found that certain regions of the brain of Buddhist monks were enlarged and different than the rest of us, through a period of spiritual practice and meditative discipline. And a lot of it had to do with positive reframing. Whenever the monks encounter something unpleasant, they reframe it.

And so they rewire their own brains through this practice. This was a concept that was unknown to me at the time. So we’re driving, I’m driving along and they’re interviewing this Buddhist monk and the interviewer from WBUR or whatever it is in Boston, says to the monk, he says, well, you know what, if you’re driving in traffic and someone cuts you off, which is like a quintessential Boston kind of thing, and I suppose the proper response in Boston would be like, I would shoot him or something, or, you know, I would crash into his car or whatever. And the monk without missing a beat, and I literally, I pulled over. I was just like, I was so stunned by what this man said. His voice calmed down. And he said, I would imagine that in that car there was a man, and in the backseat was his wife, and she’s delivering their baby.

Her baby’s about to be born, and he is desperate to get her to the hospital. And he’s driving as best he can to get her safely to the hospital. And that’s why he had to unavoidably and unnecessarily cut off this other car because a baby, a baby, a new life is being brought into the world. And I was listening to this man and calming down myself. And I couldn’t believe, it’s such a simple thing what I’m telling you now, but I just could not believe the wisdom in what I was hearing. And I resolved to really be more that way, you know, to try to deliberately renarrate the world around me, to look at the positive aspects of it.

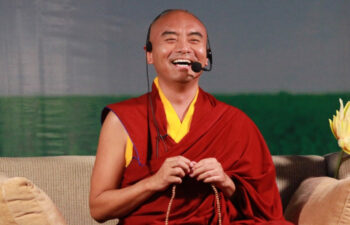

Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche:

When you look at the reality as they are, okay, you are waiting at the bathroom. So normally we have this belief, this supposed to be the line.

Devendra Banhart:

Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche is a renowned meditation teacher, author of several books on Buddhism, and head of the worldwide Tergar Meditation Community .

Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche:

Nobody cut, no one cut my line. We have so many of those. So that’s what we call permanent singularity, solid independent belief. But then suddenly someone cut your line, what happened? Okay, I know your option, so maybe that person doesn’t see you, maybe the person has emergency, maybe that person on purposely ignore you. So let’s see a little bit and maybe come, communicate, conversation. So we should think about what the reality is. It’s very important.

Devendra Banhart:

This reframe that Nicholas Christiakis is referring to, and Mingyur Rinpoche’s encouragement to see things as they really are, is about embodying the fundamental Buddhist teachings on interdependence. We are all connected, our actions have causes and effects, and the choices we make matter.

This season we’ve focused on a painting of the Wheel of Life in the Rubin Museum’s collection. The Wheel of Life, also known as the Wheel of Existence, is a foundational symbol in Buddhism and offers a visual representation and reminder of the cycle of life, death, and rebirth. To see the artwork in detail, go to rubinmuseum.org/wheel.

Again, Annabella Pitkin.

Annabella Pitkin:

The Wheel of Life is a really straightforward, ethical teaching. It very straightforwardly says directly to the viewer, Hey, you, we are all in this together. We all live in an overlapping, global web of millions of different worlds. And the Wheel of Life says, wherever you are at the moment, wake up and realize we are also here. We are all here together in this interconnected interdependent cosmos.

And we all face the same fundamental circumstances, which is the reality of change, the reality of impermanence, the difficulty of experiencing our connection to each other, and also the reality of how wonderful it is when we suddenly realize that we are actually interdependent and connected. And the wheel is saying, look, the Buddha is in all those realms. Wherever you are, don’t give up. Remember that it is always possible to notice our interconnection and to choose care and compassion and ethical action. And also the wisdom that pays attention to reality as it is that decenters perhaps what I might want right now. Because I’m also thinking about what we all might want all of us together, and I’m looking at cause and effect the reality check of our actions. So that’s one thing that the wheel says. It says, wake up to the fact that we’re all in this together and let’s start acting like we are.

Nicholas Christakis:

How you act or how you think or how you feel comes to depend on how others around you act, think, and feel. Even those to whom you’re not directly connected, your friends’, friends’, friends comes to act, think, or feel in some way. And that ripples through the network and comes to affect your life because all of us, we’re connected in this vast fabric of humanity. And so these other human beings that are at some distance from us in the social network, can actually play a very important role in our lives. And equally, we can play a role in their lives. When you make a change for the better in your life, when you quit smoking or treat others kindly or pass along accurate information, you can affect not just the people to whom you’re directly connected, but dozens, maybe hundreds, maybe thousands, in some cases, other people to whom you’re indirectly connected.

Annabella Pitkin:

The real to-do list is to act on this combined compassion, wisdom, insight of interdependence, and to show up for each other in every level of community, in all of our ecosystems, in the microcosm of our own bodily health that is inextricable from the macrocosm of our communal and global health, in our relationships with our technological processes, and with the vast web of knowledge and connection and relationship and community building that social networks afford us in this enormous universe of relationality.

Nicholas Christakis:

Just the awareness that the actions we take don’t stop at the edge of our bodies, and they don’t even stop at the edge of our families and friends that they ripple out through the network. Like a pebble dropped on a pond creates these waves that spread out and eventually reach the other side of the pond. You can imagine this sort of metaphor of waves spreading out from a hand, dropping a pebble in a pond. I think you can think of us as having that kind of an effect, that it’s important to recognize the extent to which our actions and and our thoughts and our feelings affect everyone around us.

I feel that in some way, we belong together. We belong, we are making an impression upon one another. The lived experience, the monological experience of compassion, love, and interdependence is intertwined. When you touch on true love, you’re touching on interdependence, and you’re touching on compassion. When you touch on true compassion, you’re touching on love and interdependence. When you touch on interdependence, which you cannot avoid, you’re touching on everything else, everything else.

Devendra Banhart:

Cultivating an awareness of interdependence is a process. In our full and sometimes complicated lives, filled with desire and craving for things to work out just as we want them to, it can be hard to tap into feeling the truth of our interconnectedness. But there are things we can do to practice.

Mingyur Rinpoche.

Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche:

Just bring awareness to your body and the awareness of the sensation in the body. Just watching, just being with that awareness, the craving become less automatically. If you find craving, that means you are not lost with the craving. What we call, if you see the river, you are out of river, even the river is there, but automatically you’re out of river. If you see the mountain, you’re out of the mountain. If you see the movie, you are not in the movie. So that’s the power of awareness, just observing it come out. Then of course love and compassion. So you, you see that everybody has that sensation. Everybody has the craving aversion. Everybody want to be happy, don’t want to suffer just like you, your friends, your family, doesn’t matter who they are and they all have this wonderful quality. Everybody has enlightened quality. So when you see that we all are like big family, everybody want to be happy, don’t want to suffer and then practice love and compassion with everybody.

Pamela Ayo Yetunde:

Start where you are.

Devendra Banhart:

Pamela Ayo Yetunde.

Pamela Ayo Yetunde:

We call this four foundations of mindfulness. And that basically means if you can imagine your body in four aspects, four realms, four parts, the way you breathe, the sensations in your body, then the state of your mind, the quality of your thoughts. If you can be aware of these parts of yourself without judging, then you are practicing mindfulness. And some people say, well, I forget to practice mindfulness. Like, how can I remember to do that? It can be as simple as taking a deep breath every hour, or just decide on a half hour. I’m gonna take a deep breath. Or if you’re just not accustomed to doing that, to say, you know, today, at the beginning of the day, I’m gonna take a deep breath in and out, and I’m gonna notice how it feels coming in and coming out.

This is the beginning of being aware of ourselves. This awareness then supports our ability to be in relationship with others because it actually reduces anxiety, stress, angst, and the many ways that we tense up when we’re around other people. So as we’re flexing our awareness muscle, our mindfulness muscle, our interdependence muscle, we’re not getting so tight that we cannot appreciate our surroundings. The point is to flex and then relax deeply into our being. When we can be relaxed, it is said, then we can appreciate others more because we’re not defended. This is part of the beauty of these mindfulness teachings is to help us be less defended about reality and about others. And it is said that when we are less defended, then we can appreciate more. We can be more generous, we can be less afraid. And so, the simple breathing practice, simple awareness, practice without judgment supports interdependence

Devendra Banhart:

Let’s do it together. Let’s take some breaths in and out. Breathe in. Breathe out. This very simple practice breeds awareness, or mindfulness. And with mindfulness comes wisdom.

Again, Mingyur Rinpoche.

Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche:

Wisdom means what is the ignorant we are perceiving single, permanent, independent. That’s not true. To see the opposite of that is the wisdom: It’s interdependent. Seeing that is wisdom and that interdependent comes from pieces, what we call multiplicity. That’s the impermanent. So seeing this three thing is the wisdom: Not single, not permanent, not independent. It’s interdependent. And so many causes and conditions come together and they’re changing, changing, changing.

Pamela Ayo Yetunde:

Learn to appreciate wisdom. If we would just pay attention to the ways that we engage in acts that can only produce harm, we just pay attention to that and refrain from engaging in that.

Devendra Banhart:

Metta is a Buddhist word that translates to loving kindness. It is a practice of generating love and compassion toward others, not just people we know but strangers, animals, all sentient beings. Pamela Ayo Yeutunde has a playful way of exercising this core Buddhist practice.

Pamela Ayo Yetunde:

I have a passion for glasses. Just so happens there’s a really beautiful place down the road from me down the street from me called D-Vision, because it’s on Division in Chicago. I go in there and I compliment complete strangers on the glasses that they’re wearing. Either the ones they came in with or the ones they’re about to buy. And I just kind of snuggle up. I don’t touch, but I kind of snuggle next to them. And I say, can I see you in those? I say, and I’ll tell ’em, I come right off the street. I don’t work here. I, I come right off the street for the sole purpose of affirming you. And it usually works. They will put on their glasses and they will ask me, well, what do you think? And I’ll say, ah. I’m like, yes, that’s the one. And sometimes I say, are you only limited to one pair today? ‘Cause let me see you in those. I may do this for 20 minutes. I may meet three or four people, customers, and then I’m out. And I feel like a million bucks when I do that.

We cannot have community. We cannot have neighborhood, we cannot have town, city, or state or country that are healthy without interdependence. Our democratic systems were created so that we could come together and cocreate an existence together. Recognizing that that is the fact, doing the opposite is denial of the fact.

Devendra Banhart:

Again Annabella Pitkin on the Wheel of Life.

Annabella Pitkin:

We see old age. We see death. We see this endless chain of becoming, and the whole chain of becoming this whole interdependent sequence of infinite rebirth and redeath is in the grip of this reddish brown, fearsome, demonically featured monster with the crown of skulls, the blazing three eyes, the claw like toenails and fingernails, the crown of flames. This is Yama, the Lord of death, the supernatural personification of death, and all of these, states of experience and existence, as long as they are conditioned by the three poisons at the center, the miscognition, the failure to recognize interdependence, the delusion or ignorance, the addictive craving and greed that comes from that, the hatred and cruelty and violence and jealousy that comes from that. As long as we experience our reality and we participate in our reality powered by those negative mental and psychological states, we are within this wheel in the jaws of death.

But the picture, like pictures of this kind does not only show that there is a considerable amount of real estate on the image that’s not inside the jaws of death. The whole thing is taking place in a kind of outdoor space with a spacious sky filled with light. And in the upper right hand corner on a web of clouds, on a lotus-shaped seat, there is the Buddha. And the Buddha is surrounded by a nimbus of glorious light around his entire body and also around his head. And he’s teaching a smaller figure who looks like a human being wearing perhaps monastic robes. And he’s pointing, he’s pointing at the upper left corner on which also on a web of clouds, on a lotus seat, on top of a shining disc like the moon, we see the wheel of the Buddhist Dharma. So this is a kind of instructional message. It says, the Buddha is pointing the way out from the jaws of death. The perfect freedom from distress is always present. And not only that, but the kind of cherry on the cake, the top of the picture is always gonna be to get back in there and help each other. Whatever modality we are using is to be there for each other.

Pamela Ayo Yetunde:

Not everybody makes it through, but you made it through. And here you are in my life. I’m in your life. Let’s celebrate this life together. I look after you. I care about you. I love you. I’ll be thinking about you. I want you to feel this from me. When you see me, I want you to know how special you are in this world. I don’t know your name. I don’t know where you live. I don’t know what you like, but we are both human beings, and therefore, I know something about you because we are the same species. And I know it’s important to be seen and heard and appreciated. So many people have come before us and have handed down lessons throughout time. So let’s be foolish. Put that love into the system where people are like, ah, I don’t want that. Put it out there. Put that joy into the system. Pay those compliments, right? Start up a conversation, show appreciation. Don’t wait to be invited because we’re strangers. Just be that. This is what we need right now. And breathe.

Devendra Banhart:

We are all in this together. There is no other way. When we recognize our interdependence it can wake us up to this reality and motivate us to act accordingly. As every action, big and small, has the potential to help create and sustain a better world for all.

You just heard the voices of Nicholas Christakis, Annabella Pitkin, Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche, and Pamelo Ayo Yetunde.

I am Devendra Banhart, singer, songwriter, artist, and your host.

To see the artwork discussed in this episode, go to rubinmuseum.org/wheel.

If you’re enjoying the podcast, leave us a review wherever you listen to podcasts, and tell your friends. For more stories and news from the Rubin, follow us on Instagram @rubinmuseum and sign up for our newsletter at rubinmuseum.org.

AWAKEN season 5 is an eight-part series from the Rubin.

AWAKEN is produced by the Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art with Kimon Keramidas, Gracie Marotta, Christina Watson, and Sarah Zabrodski in collaboration with SOUND MADE PUBLIC including Tania Ketenjian, Philip Wood, Alessandro Santoro, and Aaron Siegel.

Original music has been produced by Hannis Brown with additional music from Blue Dot Sessions.

AWAKEN Season 5 is sponsored by The Prospect Hill Foundation and by generous contributions from the Rubin’s Board of Trustees, individual donors, and Friends of the Rubin.

This program is supported, in part, by public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, in partnership with the City Council.

Thank you for listening.

In the final episode, we explore how to integrate what we’ve learned about interdependence over the course of this season into our lives and put it into practice. How can we implement some of the teachings from the image of the Wheel of Life? We are all in this together. There is no other way. It’s time to wake up to this reality and act accordingly.

This episode features pastoral counselor, teacher, and author Pamela Ayo Yetunde. AWAKEN season 5 is hosted by singer, songwriter, and artist Devendra Banhart. Other guests in this episode include social scientist, physician, and professor Nicholas Christakis, professor of Buddhism and East Asian religions Annabella Pitkin, and Tibetan Buddhist meditation teacher and author Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche.

Wheel of Life, attributed to Lhadripa Rinzing Chungyalpa (b.1912, Sikkim–d.1977); Sikkim; c. 1930; pigments on cloth; Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art; C2004.21.1

One of the most important teaching tools in Tibetan Buddhism is the Wheel of Life, also known as the Wheel of Existence, which demonstrates the cyclical nature of life, death, and rebirth. The scenes within the wheel portray the laws of karmic cause and effect, illustrating how a person’s actions bring about positive or negative outcomes in their current and future lives. The fierce lord of death Yama grips the wheel in his mouth, ready to swallow it at any moment, showing how everything is impermanent and in the grip of death. Beyond traditional religious teachings, the Wheel of Life also provides lessons for Buddhists and non-Buddhist alike, as it reflects the reality of our interdependent world.

Devendra Banhart is an internationally renowned musician considered a pioneer of the “freak folk” and “New Weird America” movements. Banhart has toured, performed, and collaborated with Vashti Bunyan, Yoko Ono, Os Mutantes, the Swans, ANOHNI, Caetano Veloso, and Beck, among others. His musical work exists symbiotically alongside his pursuits in the other fine arts including painting, poetry, and drawing. The Venezuelan American has released 11 albums. His drawings and paintings have appeared in galleries all over the world, including the Art Basel Contemporary Art Fair in Miami; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; Palais des Beaux-Arts in Brussels; Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles; Nicodim Gallery; and Serralves.

Pamela Ayo Yetunde is a pastoral counselor in private practice. She is the co-editor of Black and Buddhist: What Buddhism Can Teach Us About Race Resilience, Transformation and Freedom and author of Casting Indra’s Net: Fostering Spiritual Kinship and Community and Dearly Beloved: Prince, Spirituality, and This Thing Called Life.

Nicholas A. Christakis, MD, PhD, MPH, is the Sterling Professor of Social and Natural Science at Yale University. His work is in the fields of network science and biosocial science. He directs the Human Nature Lab and is the co-director of the Yale Institute for Network Science. He was elected to the National Academy of Medicine in 2006; the American Association for the Advancement of Science in 2010; the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2017; and the National Academy of Sciences in 2024.

Annabella Pitkin is associate professor of Buddhism and East Asian religions at Lehigh University. Her research focuses on Tibetan Buddhist modernity, Buddhist ideals of renunciation, miracle narratives, and Buddhist biographies. She received her BA from Harvard University and PhD in religion from Columbia University. She is the author of Renunciation and Longing: The Life of a Twentieth-Century Himalayan Buddhist Saint, which explores themes of non-attachment and teacher-student relationship in the life of Khunu Lama Tenzin Gyaltsen. More →

Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche is a recognized tulku of the Kagyu and Nyingma lineages of Tibetan Buddhism, a teacher, spiritual leader, and bestselling author. He possesses the rare ability to present the ancient wisdom of Tibet in a fresh, engaging manner. His profound yet accessible teachings and playful sense of humor have endeared him to students around the world. Rinpoche’s teachings weave together his own personal experiences with modern scientific research in relation to the practice of meditation. He has authored several books including two bestsellers: The Joy of Living: Unlocking the Secret and Science of Happiness, which has been translated into over 20 languages, and In Love with the World: A Monk’s Journey Through the Bardos of Living and Dying. His recent TED Talk is titled “How to Tap into Your Awareness—and Why Meditation Is Easier Than You Think.” Rinpoche teaches extensively around the world and oversees dharma centers, including three monasteries in Nepal, India, and Tibet, and the Tergar Institute in Kathmandu; Tergar meditation communities on six continents; numerous schools in Nepal; and social engagement projects related to health, hunger, hygiene, the environment, and women’s empowerment issues in the Himalayas.

Get the latest news and stories from the Rubin, plus occasional information on how to support our work.