Annabella Pitkin:

When Buddhists talk about interdependence, they’re really talking about the most fundamental Buddhist perspective on the way that we all exist and the way everything around us exists.

Devendra Banhart:

Professor Annabella Pitkin teaches Buddhism and East Asian Religions at Lehigh University.

Annabella Pitkin:

And this is a very straightforward concept that we can easily think about in terms of our own regular experiences. But Buddhist philosophers have spoken about this as also a very subtle kind of insight into the way our universe works. And the insight is that we exist in a dynamic infinite set of relationships to each other.

Devendra Banhart:

Welcome to season 5 of AWAKEN, a podcast from the Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art about the dynamic path to enlightenment and what it means to “wake up.”

I am Devendra Banhart, singer, songwriter, artist, and your host. In this season, we hear from experts in the realms of art, social science, Buddhism and more to better understand how interdependence is the foundation of every aspect of our lives.

Himalayan art has long been a pathway to insights and awakening, and over the course of eight episodes we look specifically at a painting of the Wheel of Life to see what it can teach us about the interconnected nature of existence.

Throughout this journey, we’ll discover how greater awareness of our interdependence can be the wake up call that motivates us to take actions for a better world.

This season, we’ll look at interdependence in the context of community, ecology, culture, and more. But first we need to get some grounding in the concept itself. And in this initial episode, I’ll play two roles—I’ll not only be your host but I’ll also share some of my personal connection to this topic.

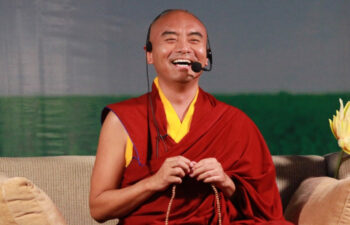

You’ll also be introduced to the people sharing their stories and insights throughout the series. Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche is a renowned meditation teacher, author of several books on Buddhism, including The Joy of Living: Unlocking the Secret and Science of Happiness, and head of the worldwide Tergar Meditation Community.

Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche:

Interdependent meaning in Buddhist teaching like everything related to each other. It’s kind of like a connections. So for example, self, when we look at the self, actually we can’t find a one independent thing, the solid thing like self related with my name, my status, my title, my experience, my body, my feeling emotion, and also what people are talking about me, like my parents view, what they view me, my friends, my colleague at workplace. And according to parents, your children, if you have children, your parents for the spouse, you are partner, all is connected, like bunch of things relating each other is connection only. There’s no single independent thing that we can define ourself, but if we accept ourself as full of connections, it’s wonderful.

Devendra Banhart:

And again, professor Annabella Pitkin, whose book Renunciation and Longing: The Life of a 20th Century Himalayan Buddhist Saint, brings Tibetan Buddhist approaches to modernity.

Annabella Pitkin:

Buddhist philosophers, going back all the way to the time of the historical Buddha Shakyamuni, 2,500 and some change years ago, have spoken about this as also a very subtle kind of insight into the way our universe works, that the Buddha is said to have had a personal experience of during his meditations in India under the bodhi tree when he became the Buddha.

The insight is that we exist in a dynamic infinite set of relationships to each other. We are fundamentally relational beings, and we sometimes don’t experience that in our day-to-day lives. We often might feel lonely or like someone else is competing with us for something. But the Buddhist claim is that that’s a kind of misunderstanding of reality, a kind of miscognition.

Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche:

Buddha has this question from beginning of early of his life, he was prince and he has the question that what is the meaning of life? What all these things come from? And he looked for this answer, he even left his kingdom. Look for this answer. And he received so many scholars, meditators at that time. But he just only got a part, only not complete. Then he thought, oh, to find the complete answer, I have to practice, determine practice. He went to near the river Narajan, six years of determined practice. But it still doesn’t work. He still didn’t get the answer. So then what he did is let go of that intellectual study, let go of that rigid meditation, let it be as it is, follow the flow of the nature, but something is coming together. What Buddha said, to see the nature of reality as they are, then you have to see balance not extreme. To see the balance is through interdependent view. So then Budhha went to Bodhgaya, achieved enlightenment, fully enlightened. So then what he said, the view, the perspective is the middle way, meaning not fall into the extreme, balance, the middle way. Your meditation also middle way, not rigid concentration, not totally lost. Being the, the mind as they are, your action also find the middle way, not rigid, so many cause and condition, you have to find the balance. So there’s the whole thing in Buddhism is based on the interdependent interconnection view that find the middle way.

Annabella Pitkin:

We are always interconnected with everyone else and with all the phenomena of the universe all the time.

Nicholas Christakis:

The way I describe interdependence in human groups is by reference to a metaphor from chemistry.

Devendra Banhart:

Professor Nicholas Christakis is a social scientist and physician who conducts research in the areas of social networks and biosocial science, and directs the Human Nature Lab at Yale University. He is the author of several books including Connected: The Surprising Power of Our Social Networks and How They Shape Our Lives.

Nicholas Christakis:

Most of us are familiar with graphite and diamond. But these two objects have very different properties. One is soft and dark, and one is hard and clear. And there are two key intellectual ideas there. First of all, these properties of softness and darkness and hardness and clearness are not properties of the carbon atoms. They’re properties of the collection of carbon atoms. And second, which properties you get depends on how you connect the carbon atoms to each other. Take the same carbon atoms and connect them one way, and you get graphite, which is soft and dark, or connect them another way, and you get diamond, which is hard and clear. It’s the same with human groups.

And this is a very deep and interesting idea in the sciences. It’s related to what’s known as emergence, how collections of things can have emergent properties. So collections of people, depending on how they’re connected, can have these emergent properties by reference to the carbon example, where the softness and darkness and hardness and clearness are emergent properties of the carbon atoms.

Annabella Pitkin:

Interdependence then sets the stage for really important things Buddhists want to talk about, that involve ethics and compassion and loving kindness and how we respond to one another, and that also relate to important things Buddhists want to say about wisdom, about the direct experience of reality as it is in a way that Buddhists describe as profoundly liberating.

Devendra Banhart:

This season we’re focusing on a painting of the Wheel of Life in the Rubin Museum’s collection. The Wheel of Life, also known as the Wheel of Existence, is a foundational symbol in Buddhism and is usually displayed near the entrance of temples and monasteries. It offers a visual representation and reminder of the cycle of life, death, and rebirth. The Wheel is a perfect tool for better understanding the concept of interdependence, and students have turned to it for thousands of years for this reason. To see the artwork in detail and learn more, go to rubinmuseum.org/wheel.

Here Annabella Pitkin explains the origins of the Wheel.

Annabella Pitkin:

This image is said to be one of the earliest kinds of images that Buddhists used as a teaching tool. In fact, it’s so fundamental that in a wonderful story about the life of the Buddha Shakyamuni, during his time on earth in India, 2,000, maybe 5 or 600 years ago, there’s a description of how the Buddha Shakyamuni, after his enlightenment, began to turn the wheel of the Dharma, he began to teach. And he taught some companions and some people who were drawn to him by his remarkable personal qualities and a kind of atmosphere of peacefulness and liberation that is described as surrounding him.

And he also very quickly began to teach people from his own family who he quickly reconnected with. We often don’t emphasize this part of Shakyamuni’s biography: He leaves home very dramatically as a young man to look for the path to enlightenment. But then, very importantly, he goes back and he teaches his family and relatives, but one relative isn’t available on Earth to learn the teachings. And that is his biological mother, Queen Maya, who according to the legends of Shakyamuni’s birth and early life, dies when he’s only seven days old. And she goes immediately to a heavenly realm. And then she kind of watches the proceedings from that heavenly realm. So in the wonderful legends that surround the life of the Buddha Shakyamuni, there’s a very touching description of how he has not forgotten her. And he ascends to this heavenly realm, which is inhabited by various kinds of gods, deities from the Indic pantheon.

And there is his former mother. And so he resides there for a time in this heavenly realm so that he can teach there, too. And she too will have the opportunity to receive the Buddhist teachings, and then he returns to Earth. So why am I telling that story now? Well, it’s because people on earth are very sad, according to this legend, when Shakyamuni prepares to ascend to teach his mother. And so to give them some comfort and some access to the teachings while he’s busy somewhere else, he leaves what is described as being an early illustration of the Wheel of Life. So that gives a sense of how useful and helpful a visualizing teaching tool this Wheel is said to be. And in the version that we see here, that we’ll be talking about, we see both the kind of moment in time, relationality, web of connections between different kinds of experiences that are possible in the universe. And at the same time, we see this quality of dynamism, of processes, of constant motion, and relational change.

Devendra Banhart:

The Wheel of Life has many detailed parts that illustrate the laws of cause and effect, the process of rebirth, and the sources of suffering and the path to liberation. We won’t be able to explore every aspect of it; instead the following episodes will primarily focus on each of the realms of existence where it is possible to be reborn. Across the varied, sometimes chaotic imagery for those realms, one figure is consistent: the Buddha.

Annabella Pitkin:

When we look at this image of the wheel of life, this particular image has five regions, five main realms of existence. Many images actually have six realms of existence because the realm of the gods in many images is divided into two. And the images of the different realms are all experiences that living beings can have, do have, are having according to Buddhist literature in what Buddhist calls samsara, which is the endless cycle. That’s why we have a wheel, the endless cycle of death and rebirth in a new life and re death and rebirth and re death, which is an infinite cycle.

The Buddhist analysis of the interdependent cycle of death and birth is that it has no beginning and it has no end. It’s an infinite natural process that’s always occurring. And we who are experiencing ourselves as humans at this moment, have been participating in this cycle, this interdependent cycle of birth and death since beginningless time.

And so we’ve actually experienced all the different states that are represented in the wheel of life over and over and over and over again, times infinity. We’ve been all the characters. Every single one of the pictures is us. We’ve done all of those things.

One of the things we might notice in the image is that in every single one of the five panels that we see, there is an image of the Buddha standing in some of the panels. And then there are lots of other kinds of beings in each of the panels. So whatever it means that the Buddha is free within this situation, it doesn’t mean that he’s gone or that he’s abandoned beings. And that is a very interesting choice by the artist, which suggests that the goal of the path is actually to become a Buddha oneself.

Devendra Banhart:

Becoming a Buddha simply means to wake up, to see reality as it is. And what happens when we truly wake up to the reality of our interconnectedness? Throughout this series, we will hear from various people about how interdependence shapes their lives, and how greater awareness of it motivates small but meaningful actions to cultivate a better world for all.

In this first episode, I am excited to share what interdependence means to me, as a musician, artist, and human being.

Interconnectedness is a very, very real thing. The bliss of not just living in your little bubble of yourself, of the world is this movie called you and everyone is an extra in your movie. What a gift to for once know that you’re a part of this thing and it is interconnected. You are interdependent.

The world says be independent. The world says be independent. It’s just you. And win and get it. Get it, get it. Oh, get it, get it, get it is hell and there’s nothing more hellish than a conversation about winning and getting. A concrete way that I practice something like remembering how interconnected we are would be a very Buddhist thing, which is mother recognition. Mother recognition works. I see you and you’re just a stranger and I don’t know you and I don’t know you. Okay there, I don’t know you. Keep on moving or I see you, I don’t know you, but for a moment I go, I used to be your mom. You used to be my mom. And it just, oh my goodness. Does it change the way I perceive the world? It just makes, someone cuts me off. Somebody’s rude to me. And people are, it happens all the time. And just that angry, oh, I used to be here. I used to be here. Your mom. Oh, sweet. I mean, I suddenly can be, I mean, I actually can be really patronizing suddenly when someone’s really mean to me and I can just be like, oh, a little sweetie baby. I just imagine my little baby and it just totally diffuses the situation. I’m no longer dealing with a stranger. I’m dealing with somebody who used to be my mom. Or I was theirs. So that’s an incredible tool.

The most interconnected experience of my life happened at Green Gulch. I had just finished lunch. This is like a retreat, and I ate so much. Food is so good there. It’s just some brown rice and vegetables, but it is so tasty. I could not get enough. I feel like there was food coming out of my mouth. I could barely walk. And I was like, I better walk to the Muir Beach. So I walk, I’m walking the beach, and then on the way from Green Gulch to the beach, you see the farm, you see all these patches of cauliflower and stuff and that’s it. I just looked at them and there was no more Devendra. I just dissolved into that field of cauliflower and I thought I was going to float away. I thought I was going to, I felt that myself, levitating felt like transference of consciousness and it was just from being in that environment where there really is true interconnectedness.

I think in day to day like existence, it is this feeling of knowing I’m sharing air and you breathe in and you breathe out and you remember that this air is being shared with everyone and it kind of makes it a little less easy to be disgusted all the time. And I was so relieved by this great quote that Lama Rod Owens has about his teacher saying to him, you don’t have to like everybody, but do you have to love everybody. And I just love that so much.

You just heard the voices of Nicholas Christakis, Annabella Pitkin, and Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche.

I am Devendra Banhart, singer, songwriter, artist, and your host.

To see the artwork discussed in this episode, go to rubinmuseum.org/wheel.

If you’re enjoying the podcast, leave us a review wherever you listen to podcasts, and tell your friends. For more stories and news from the Rubin, follow us on Instagram @rubinmuseum and sign up for our newsletter at rubinmuseum.org.

AWAKEN season 5 is an eight-part series from the Rubin.

AWAKEN is produced by the Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art with Kimon Keramidas, Gracie Marotta, Christina Watson, and Sarah Zabrodski in collaboration with SOUND MADE PUBLIC, including Tania Ketenjian, Philip Wood, Alessandro Santoro, and Aaron Siegel. Original music has been produced by Hannis Brown with additional music from Blue Dot Sessions.

AWAKEN Season 5 is sponsored by The Prospect Hill Foundation and by generous contributions from the Rubin’s Board of Trustees, individual donors, and Friends of the Rubin.

This program is supported, in part, by public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, in partnership with the City Council.

Thank you for listening.

Interdependence is so foundational to every aspect of our lives that it can be easy to miss. But what happens when we truly wake up to the reality that everyone and everything is interconnected? For centuries people have turned to the image of the Wheel of Life to better understand cause and effect and the very nature of existence. How do the teachings of the Wheel still apply to our world today?

AWAKEN season 5 is hosted by singer, songwriter, and artist Devendra Banhart. Guests featured in this episode include social scientist, physician, and professor Nicholas Christakis, professor of Buddhism and East Asian religions Annabella Pitkin, and Tibetan Buddhist meditation teacher and author Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche.

Complete our listener survey for a chance to win two free tickets to the Rubin’s Mindfulness Meditation program in person or online.

Wheel of Life, attributed to Lhadripa Rinzing Chungyalpa (b.1912, Sikkim – d.1977); Sikkim; c. 1930; Pigments on cloth; Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art; C2004.21.1

One of the most important teaching tools in Tibetan Buddhism is the Wheel of Life, also known as the Wheel of Existence, which demonstrates the cyclical nature of life, death, and rebirth. The scenes within the wheel portray the laws of karmic cause and effect, illustrating how a person’s actions bring about positive or negative outcomes in their current and future lives. The fierce lord of death Yama grips the wheel in his mouth, ready to swallow it at any moment, showing how everything is impermanent and in the grip of death. Beyond traditional religious teachings, the Wheel of Life also provides lessons for Buddhists and non-Buddhist alike, as it reflects the reality of our interdependent world.

Devendra Banhart is an internationally renowned musician considered a pioneer of the “freak folk” and “New Weird America” movements. Banhart has toured, performed, and collaborated with Vashti Bunyan, Yoko Ono, Os Mutantes, the Swans, ANOHNI, Caetano Veloso, and Beck, among others. His musical work exists symbiotically alongside his pursuits in the other fine arts including painting, poetry, and drawing. The Venezuelan American has released 11 albums. His drawings and paintings have appeared in galleries all over the world, including the Art Basel Contemporary Art Fair in Miami; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; Palais des Beaux-Arts in Brussels; Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles; Nicodim Gallery; and Serralves.

Nicholas A. Christakis, MD, PhD, MPH, is the Sterling Professor of Social and Natural Science at Yale University. His work is in the fields of network science and biosocial science. He directs the Human Nature Lab and is the co-director of the Yale Institute for Network Science. He was elected to the National Academy of Medicine in 2006; the American Association for the Advancement of Science in 2010; the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2017; and the National Academy of Sciences in 2024.

Annabella Pitkin is associate professor of Buddhism and East Asian religions at Lehigh University. Her research focuses on Tibetan Buddhist modernity, Buddhist ideals of renunciation, miracle narratives, and Buddhist biographies. She received her BA from Harvard University and PhD in religion from Columbia University. She is the author of Renunciation and Longing: The Life of a Twentieth-Century Himalayan Buddhist Saint, which explores themes of non-attachment and teacher-student relationship in the life of Khunu Lama Tenzin Gyaltsen. More →

Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche is a recognized tulku of the Kagyu and Nyingma lineages of Tibetan Buddhism, a teacher, spiritual leader, and bestselling author. He possesses the rare ability to present the ancient wisdom of Tibet in a fresh, engaging manner. His profound yet accessible teachings and playful sense of humor have endeared him to students around the world. Rinpoche’s teachings weave together his own personal experiences with modern scientific research in relation to the practice of meditation. He has authored several books including two bestsellers: The Joy of Living: Unlocking the Secret and Science of Happiness, which has been translated into over 20 languages, and In Love with the World: A Monk’s Journey Through the Bardos of Living and Dying. His recent TED Talk is titled “How to Tap into Your Awareness—and Why Meditation Is Easier Than You Think.” Rinpoche teaches extensively around the world and oversees dharma centers, including three monasteries in Nepal, India, and Tibet, and the Tergar Institute in Kathmandu; Tergar meditation communities on six continents; numerous schools in Nepal; and social engagement projects related to health, hunger, hygiene, the environment, and women’s empowerment issues in the Himalayas.

Get the latest news and stories from the Rubin, plus occasional information on how to support our work.