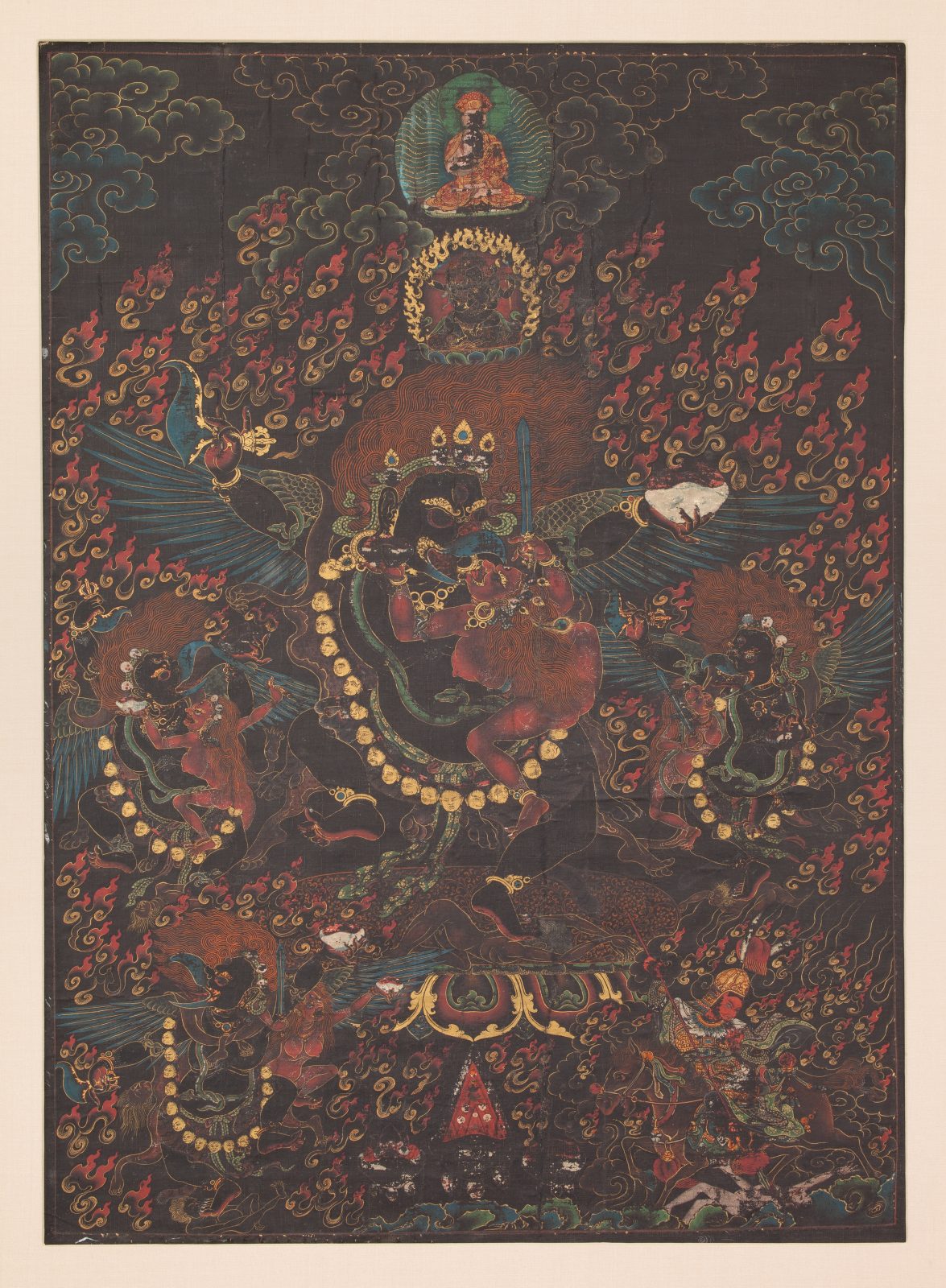

Raven-headed Mahakala; Bhutan; early to mid-19th century; Pigments on cloth; Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art; C2006.42.8

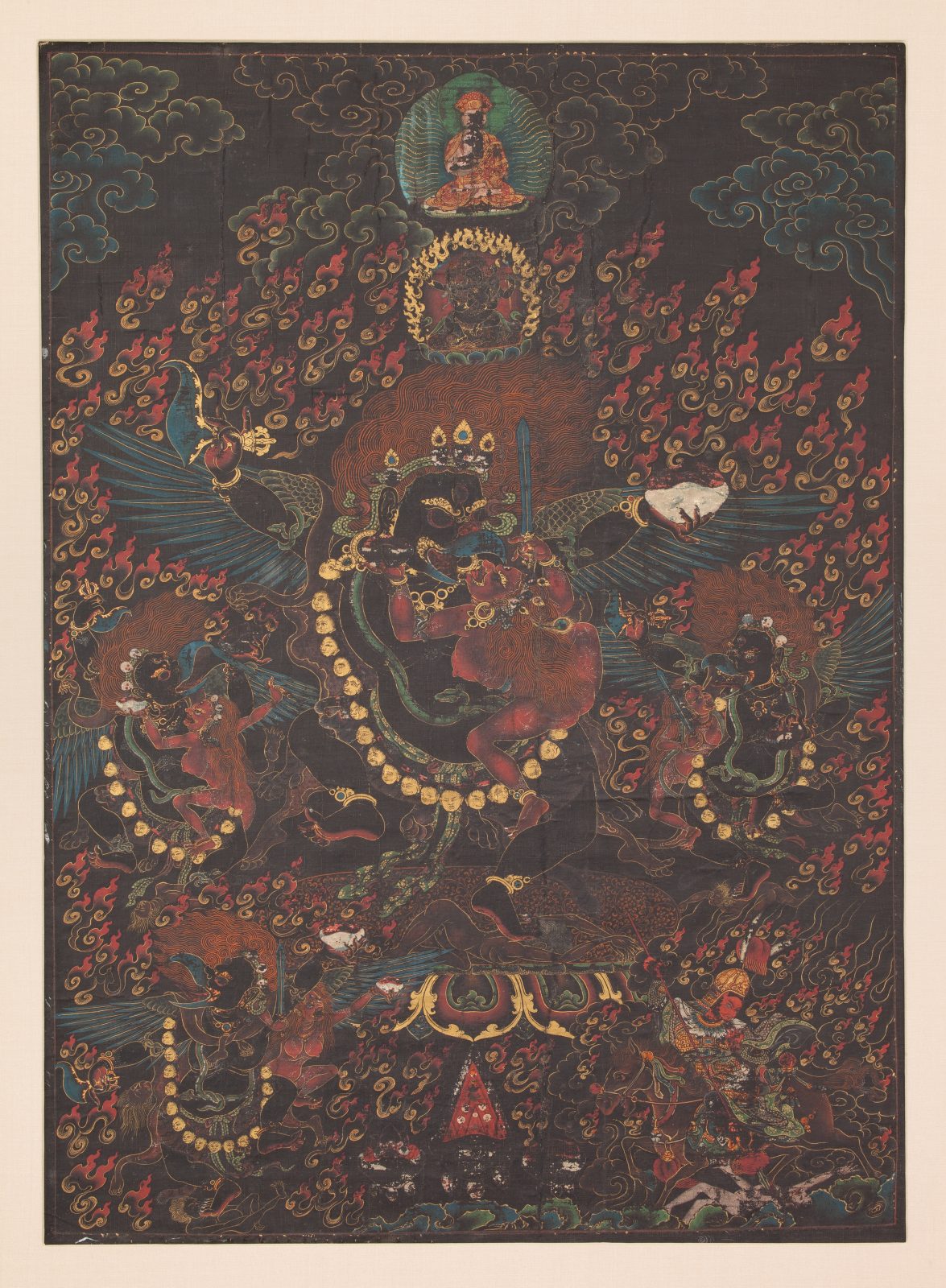

Raven-headed Mahakala; Bhutan; early to mid-19th century; Pigments on cloth; Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art; C2006.42.8

The art in the exhibition Faith and Empire depicts empires and emperors that have long since fallen, but it also draws connections between religion and politics that are still relevant today. In an increasingly secular world, we might think that religion is less of a political force than it was in the past. Yet faith remains not only a practice of personal devotion but also a source of national identity and tool of political power. Empires also are not a relic of the past; the United States extends its military power and cultural influence throughout the world, while other nations seek to expand their own realms of control.

Religious symbols are one key to the power of historic and modern empires. Tangut, Yuan, and Qing rulers worshiped the protector deity Mahakala to attain success in battle, and he became patron of the realm. These rulers also sponsored depictions of themselves as compassionate bodhisattvas—Qing emperors as Manjushri, and the Dalai Lamas as Avalokiteshvara—spreading the dharma to their realms. Rulers today do not portray themselves as gods (not overtly, at least), but religious imagery retains its power as a national symbol, even beyond openly religious states like the Islamic Republic of Iran. Although the American Constitution forbids the establishment of an official religion, the motto “In God We Trust” appears on money, and elected officials swear oaths of office on Bibles. Even in secular Britain where church attendance is shrinking, the queen heads the Church of England and religious trappings abound in the monarchy’s symbolism.

Throughout history, rulers have reclaimed past imperial glories by reclaiming past faiths. The Mongol Yuan dynasty created a model for patronizing Tibetan Buddhism and its lamas, which succeeding dynasties imitated to legitimize their conquests. Today the atheist Communist Party rules China, not an emperor with faith in Tibetan Buddhism. Yet like the past Qing emperors, the Chinese government claims authority over Tibet’s reincarnating lamas, and President Xi Jinping has suggested that nomads consider him a living bodhisattva. Outside of Asia, President Vladimir Putin has allied with the Russian Orthodox Church to claim the former glories of the Tsars. Leaders of the United States often invoke its own religio-historical mythology, such as the City on a Hill, a biblical metaphor of the ideal community originally affirmed by Puritan settlers, and Manifest Destiny, a belief in the divine sanction to conquer in the name of democracy.

The exhibition Faith and Empire: Art and Politics in Tibetan Buddhism was on view at the Rubin Museum from February 1 to July 15, 2019.

William Dewey was formerly a curatorial fellow at the Rubin Museum. He completed a PhD in Tibetan Buddhism from the University of California, Santa Barbara, and spent a year teaching at the Rangjung Yeshe Institute in Kathmandu.

Rubin Museum

150 W. 17th St., NYC

Get the latest news and stories from the Rubin, plus occasional information on how to support our work.