Tim McHenry:

Do you feel like you’re running out of time? Are you able to stop time? If so, how? Welcome to about time, an audio series from the Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art that aims to reframe the concept of time and perhaps our perspective on life. I’m your host, Tim McHenry. Many objects in the Rubin’s collection of Himalayan art reflect the Buddhist concept of the present, highlighting the illusionary nature of the past and future.

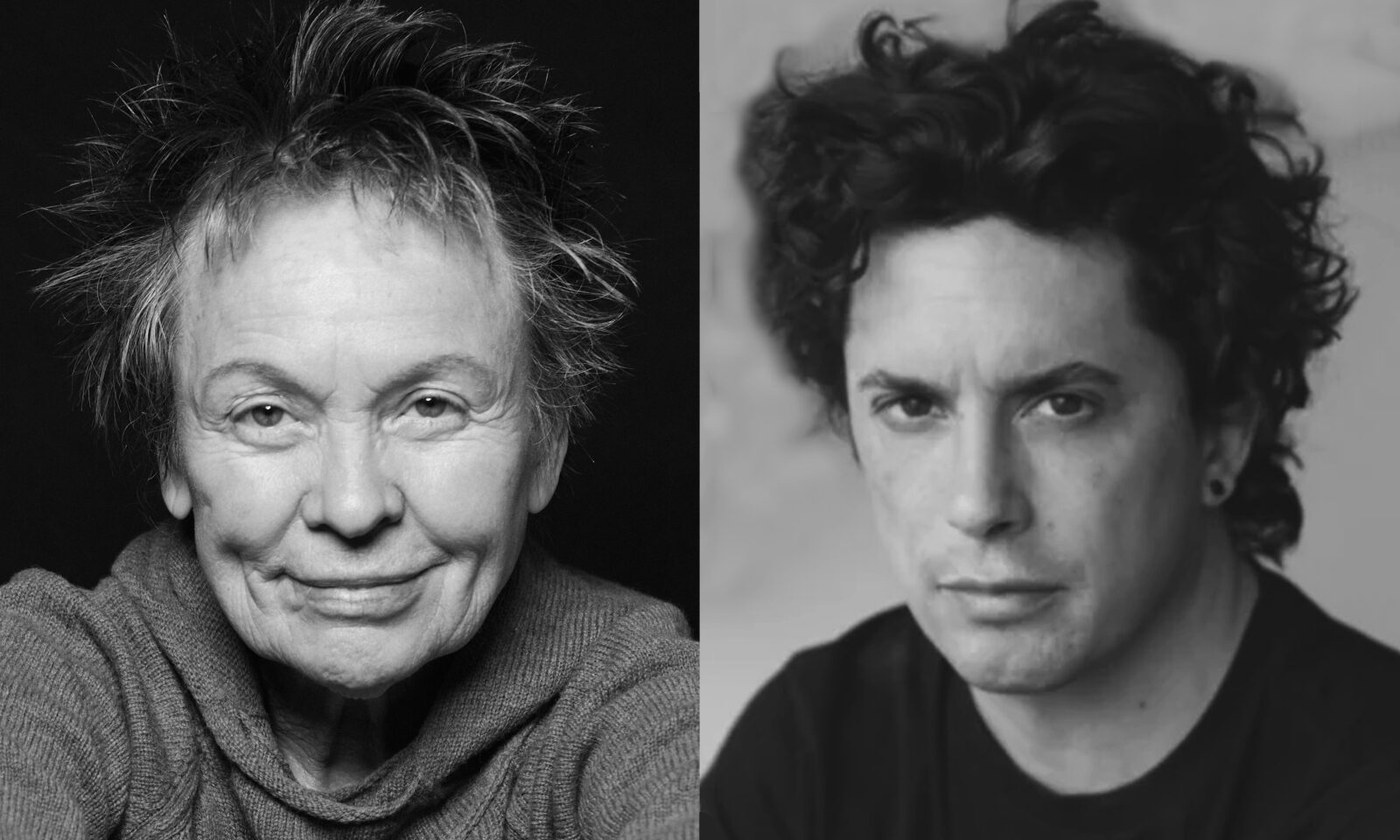

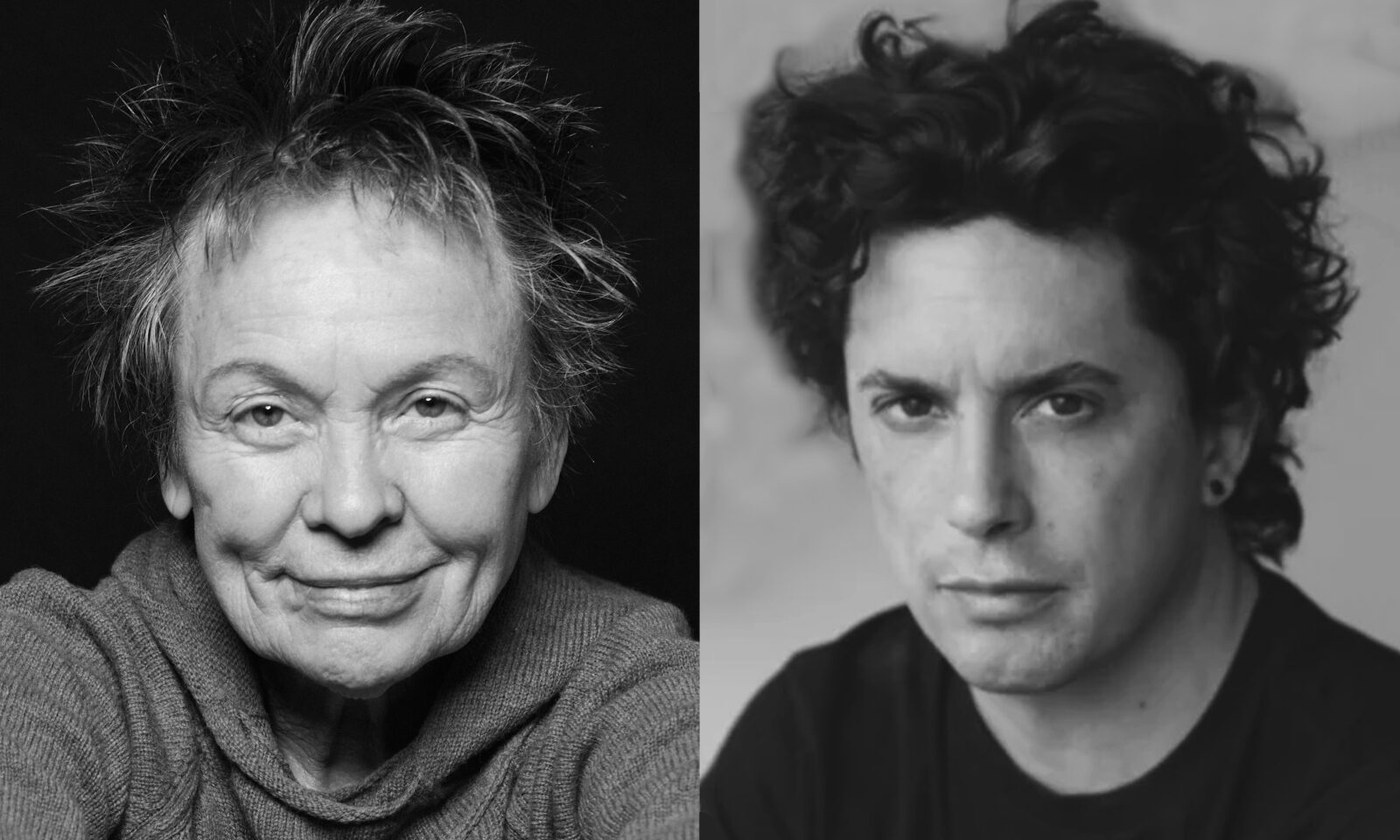

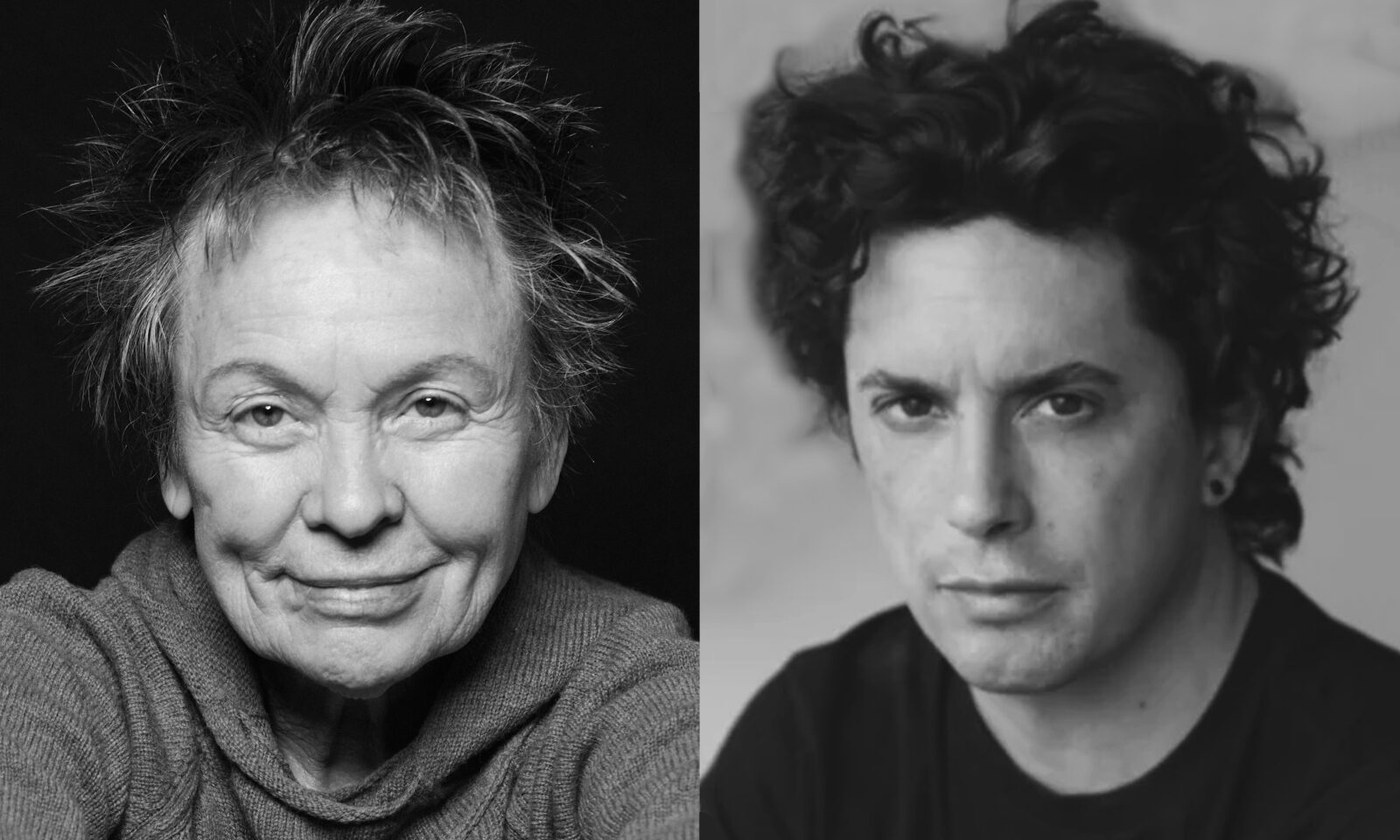

In this four part series, performance artist, electronic music pioneer, filmmaker, and all around creative genius Laurie Anderson curated a series of conversations to tackle questions about time. Laurie’s guests were poet Jane Hirschfield, novelist Tom McCarthy, philosopher the Venerable Tenzin Priyadarshi, and writer Benjamín Labatut. This is a recording of a 2024 in-person program, one of many organized and hosted by me at the Rubin.

In this episode, we hear a conversation between Laurie Anderson and Benjamín Labatut, the Chilean author of When We Cease to Understand the World. Together they try to address the horror in what is real and what is not. The examples they bring up are the mystery of déjà vu, Borges’s Second Refutation of Time, and the paradox of the Czech writer Václav Havel being “turned into an airport.” And find out why Labatut thinks that a blissed-out writer is a death sentence for creativity.

Laurie Anderson:

It’s so nice to be here and thank you so much for making your way here. I want to talk about a little bit about text and mania, horror, and violence.

Benjamín Labatut:

I broke every single one of my rules, which is don’t talk about things you don’t know anything about. Time being one of them. And never get on stage with someone who’s more interesting than you are because you make a fool of yourself. But I’ve been looking forward to this since last year and dreading it. It’s given me I’ve been cramming like I was back in school.

Laurie Anderson:

Dread is good though. I mean, I really think it can help and I’m glad you mentioned what seems real and what, this is one of the reasons I wanted to do this series because there’s something very weird going on these days and it has to do with what’s real and what isn’t. And when I read your books in a certain way, I feel that you’re looking at that in one of the most interesting ways of any writer that I know. And so this feeling that we’re not, that this is some kind of a dream and that how it affects our social and political life and the life of what books have to say to us. And maybe the other part of having the Bible co-opted is we don’t really know what texts we’re going to go along with these days. So those of you who are just so lucky, you get to read this incredible book, which for me, when things click into place immediately in the book, when the color of the sky gets connected to an idea of poison, that’s like crack for me. I mean things click and I’m like, whoa, is this whole book going to click like that or what’s the click going on here? You’ve described yourself as an epiphany junkie.

Benjamín Labatut:

Oh, absolutely. I mean, I don’t think you can have enough of them. That was a bit of a mad boy when I was young. And part of that…

Laurie Anderson:

What does a mad boy mean?

Benjamín Labatut:

Well, I did feel a little bit unmoored in time because I used to have uncontrollable déjà vu all the time and I didn’t have anybody to talk about it with because, I’m sure there must be people here in the audience where it’s like, I’m insane. You don’t want to talk about these things. So I spent lots of years and I would use it. I would start to train it. I realized I could trigger it and it gave you, this is what you do when you don’t have access to drugs when you’re young,

So you’re lying by the pool. And I would trigger these feelings of déjà vu. The combined effect of that is that I felt as we all do when we have déjà vu, that it was all being played back, but then it got out of control and then it was like I would fall into these loops and I would tell my mom I was very young and I’d be like, say what you just said. Just say it again. Just say it again. And it was maddening because it really felt like that plasticity that the brain has, if you are lucky enough to be just a little twisted but not too twisted, very important. It gives you an immediate sense of suspicion growing up. You just feel, and that’s how it relates to the epiphany because really epiphanies come from truth seeking and then you can get lost in truth in ways that are very dangerous. But if you don’t have that, if you don’t have that pull, if you don’t have that suspicion that it might just be your consciousness stitching things together, it might just be that time, in physics, it’s not there in the major equations, it’s not there. All the major equations of physics are time reversible. So these very old ideas, how time springs from the mind when you feel that you don’t have the intellectual apparatus to understand what’s going on, it gives you this sort of haunted upbringing, which I find very useful now for writing.

Laurie Anderson:

Yeah, I mean I think that the timeline thing is useful in songwriting too, this kind of this looping kind of quality of things and recognizing a thing again and again in a slightly different way. I mean, I did always connect that with drugs though, because norepinephrine is supposedly is one explanation for déjà vu. I mean the part of half of your brain that experiences something if there’s a shortage, doesn’t communicate it for 0.001 seconds. So you did have that experience before, but not years. It was 0.001 seconds ago. And I could imagine as a kid that it would be sort of thrilling too, wasn’t it?

Benjamín Labatut:

No, it felt like a prison. It always felt because I really have avoided, this is why I feel so insecure in this talk because I have consciously avoided time as a subject. I think it’s one of those mysteries that is just too large. I leave it to people like Borges, right? Borges was, time is basically his main focus on things and I could, the way he does, he has this text called the Second Refutation of Time, basically goes into it and says, yes, this is a product of the mind. So it doesn’t exist as such, comes to many of the same conclusions that some of modern physics has. But then at the end, because he is a writer and writers feed on paradox, texts need paradox in it to be alive. He goes through all of the arguments against the existence sometime and ends up saying, time is a river, but I am the river. Time is a tiger that destroys you, but I am the tiger. Time is a fire that ravages, but I’m the flame. The world is real. And he says, unluckily, I am Borges. So all of the things that are there, the things that how it is completely inextricable from our sense of self, how dangerous it is to fool around with it. I mean it is quite dangerous to mess with your ideas of time.

Laurie Anderson:

There’s a glorious story that I’m not sure whether it’s apocryphal or not, maybe it’s also been attributed to Robert Graves, but the story is Alexander the Great was not killed at the Battle of Macedon like everyone thinks he was, but he was captured by some people who forced him to fight in their army as a slave. Finally, they realized what a good fighter he was and they gave him a bag of coins. This was after 30 years, and on the coins is his own picture. And he said, oh, this is from the time when I was Alexander the Great. And this idea of identity as well is very, very tied into his time.

Benjamín Labatut:

At the beginning of artificial neural networks, the first model of a neuron was made by two men called Walter Pitts and McCulloch, and they used Boolean algebra to model a very simple neural network where you get inputs, there’s a logical calculus and an output, right? And then they had this model going, but they had a problem very paradoxical, where something happened at time T one and that it would loop back and it will get caught in loop. And Pitts did something that mathematicians and physicists are want to do. He just removed time from the equations, he said, and it worked spectacularly and not only did it work, the whole model came alive when he removed time from the equations used modern mathematics. But then the wonderful thing is that if you think about this neural network where you see a bolt of lightning and that gets caught in your neurons, but if it starts to loop and it’s like an idea pulled out of time is how you wouldn’t code a memory. So in this first mathematical model of a neuron which gave rise to the idea of the brain as a computer, as a logic driven calculus, contains this beautiful little image of a loop, paradoxical loop. You have this idea torn out of time, and these are the things that we carry around as memory.

Laurie Anderson:

Tearing out of time reminds me of your description of the black hole of this rip, which is so, such a beautifully written part of your book.

Benjamín Labatut:

Don’t say that. I want to read that one.

Laurie Anderson:

You’re not going to read that.

Benjamín Labatut:

No. Yeah, but if you say, it’s so beautiful and I read it, it’s embarrassing.

Laurie Anderson:

I didn’t like it that much.

Benjamín Labatut:

No. Well, it is a little bit. It’s Wikipedia-ish. Yeah. Should I read that one? Yes, please. Okay. Hold onto your hats.

Laurie Anderson:

Okay.

Benjamín Labatut:

The problem arose when too much mass was concentrated in a very small area as occurs when a giant star exhausts his fuel and begins to collapse. According to Schwarzschild’s calculations, in such a case space time would not simply bend, it would tear apart. The star would go on compressing and its density would increase till the force of gravity became so powerful that space would become infinitely curved closing in on itself. The result would be an inescapable abyss permanently cut off from the rest of the universe. They call this the Schwarzschild singularity. Initially even Schwarzschild cast this result aside as a mathematical anomaly. After all, physics is rife with infinities that are nothing more than numbers on paper, abstractions that do not represent real world objects or that simply indicate calculating errors. The singularity in his metrics was undoubtedly one of these, a mistake, an oddity, a metaphysical delirium. Because the alternative was unthinkable at a certain distance from Schwarzschild’s idealized star, the equations of general relativity went mad. Time froze, space coiled around itself like a serpent at the center of that dying star. All mass became concentrated in a single point of infinite density for Schwarzschild that such a thing could exist and the universe was inconceivable. Not only did it defy common sense and cast doubts on general relativity, it threatened the very foundations of physics.

As within the singularity, the notions of space and time themselves became meaningless. Schwarzschild attempted to find the logical solution to the paradox he had created. Did the fault lie in his conceit, had he simply been too clever for his own good. Because in the real world there was no such thing as a perfectly spherical, completely immovable star with no electrical charge. Surely the anomaly arose from the ideal conditions that he had tried to impose on the world, impossible to replicate in reality. His singularity he told himself was nothing but an imaginary monster, a paper tiger, a Chinese dragon, and yet he could not get it out of his head, even immersed in the case of war the singularity spread across his mind like a stain superimposed over the hellscape of the trenches. He saw it in the eyes of the dead horses, buried in the muck, in the bullet wounds of his fellow soldiers, in the shadowy lenses of their hideous gas masks. His imagination had fallen prey to the pool of his discovery. With alarm he realized that if his singularity were ever to exist, it would endure until the end of the universe. Its ideal conditions made it an eternal object that would neither grow nor diminish, but remain eternally as it was. Unlike all other things, it was immune to becoming and doubly inescapable in the strange spatial geometry it generated, the singularity was located at both ends of time. One could flee from it into the remote past or escape to the furthest future, only to encounter it once more.

Laurie Anderson:

Both ends of time. There it is. You’re writing about time.

Benjamín Labatut:

Yeah. Yeah. I realized I had, but it’s basically ripping Borges off all the time.

Laurie Anderson:

I just also appreciate your work so much as horror film because this is, I mean, your description of this singularity to me, I sometimes see it as almost cartoonish and because it’s so unthinkable, but also as pure horror.

Benjamín Labatut:

I think it keeps us alive. I think singularities are what keeps us alive. I think it’s those things that are still wrapped in mystery that remain paradoxical, inconceivable, and these limits of our thinking, these monsters of logic, these things that arise maybe from mathematics, maybe from the mind, maybe from the real world. These are the wondrous horrors that keep us on our toes and alive and raw really. I mean, any of these things gets into your head if you interact with any of these monsters and it becomes flesh. I tend to choose stories where the word becomes flesh, where there’s a certain Cronenberg aspect to it, because if these things exist inside us, then we are by far the most, I mean, I think we do. We are undoubtedly the most special, wondrous thing that’s ever been created, that these things can arise from our mind is spectacular, that they exist outside of us in space and time is also wondrous. The things that we know about how the universe works, we pretend that they’re not there. Time goes faster at your head, at eye level than at your feet. And this is something measurable. It’s not arcane physics. You can measure it, and yet we have to live as if it doesn’t. We’re all caught in this little bubble of present, and we know that there’s all these presence around us that are very different. Then people like Borges are just kind of shrieking that it’s there. It’s pointing to the monsters underneath the bed.

Laurie Anderson:

I think we all spend a lot of energy pretending stuff isn’t there now. We’re making statues or statues out of data and thinking that they’re sort of alive in some way when it’s just, I’m not buying it.

Benjamín Labatut:

Sure. I am interested in their delirium. Now they’re calling it confabulation because it’s the proper term, but I will die calling it hallucination because just the fact that as soon as you create something that even mirrors part of our capacity for thinking, it becomes delirious. It adds things to the world that weren’t there. And that is something to me that is horrible and it’s going to be a permanent problem because they are as unreliable as we are.

Laurie Anderson:

I don’t know. I don’t see it as a problem. I just see so many myths are about things turning into something else. The frog is a prince and the girl is a tree. And then I had a weird experience of a friend. We were good friends of this, the Czech Václav Havel, and after he died, I was just coming into Prague and I suddenly saw his name really big and I thought, whoa, my friend has turned into an airport and this is happening all the time. People were really very fragile. We’re not just, we’re barely here. I mean, I appreciate the fact that you want to embody things and ideas and people, but we’re so barely here. Our minds are the only things that are really actually here.

Benjamín Labatut:

I think we all carry a nuclear warhead inside our heads. The thing that we use to interact with reality is such a very small part of this incredibly deep, dangerous, and dark landscape. And I try to bring that out in writing because to me, literature, it’s like a habit of shadows. It’s a cockroach. You’re looking for where the light doesn’t shine. We sort of shine this light out with reason and with our eyes and everything can explore in a second as soon as you close them. So there’s this whole thing. I will be afraid, really afraid of anything that is AI when it has even the semblance of a subconscious. And I’m not saying that that’s inconceivable, but it’s like we’re scratching the surface of one of our faculties. But I think we are these wonderful savages and they don’t stand a chance, not against us.

Laurie Anderson:

I agree. I mean, I do love the way they use language though. I find this really completely entrancing. I use those things every day.

Benjamín Labatut:

You might become a future saint for these AI people because you already did we have your Laurie bot, right? With all your writings? No.

Laurie Anderson:

Yeah, yeah.

Benjamín Labatut:

You jump the queue.

Laurie Anderson:

Well, yeah. Jump is not the only one with this Bible. I was like, maybe it was four years ago when I was working at the Machine Learning Institute in Adelaide, and it’s the largest language supercomputer in the world, and they said, you’re the artist in residence here. What do you want this thing to do? And I said, it’s a supercomputer. Can’t it figure out its own projects? Does it need me to make suggestions? I so I did suggest that let’s teach it to read the Bible. And so we put the three languages that feed into the English Bible, Hebrew, Aramaic, Greek, and you could then control the amounts of those languages in each chapter in verse. And so the question was, if you have the Greek fader way up, is it more rational if you have the Hebrew fader up? Is it more mystical? It’s pretty inconclusive. Really?

Benjamín Labatut:

Yeah, because they average things out, right? Because they’re predictive. They have to, the way they’re set up to work, the ones that are running now, they kind of take the middle road and it’s hard to get them to move in any other direction. And in that I think they’re very much like we are right? Our brains are sort of making all these calculate… We’re very lazy. It’s like, what is the least amount of effort I can get something good at from my brain?

Laurie Anderson:

Hey, where’d you get the title? When We Cease to Understand the World?

Benjamín Labatut:

That’s not the title. The title is, Un Verdor Terrible, which is a beautiful title, not translatable, though it sounds horrible in every other language, so it has five different titles, but When We cease to Understand the World was the heading of the chapter that was dedicated to quantum physics, because to me that is such, I mean, it’s kind of a horse I’ve kicked to death, but it is an awakening moment for science. What happened with Heisenberg and Schrödinger and what they did was really, to me, it was when science had to put on grownup pants, people started to sound like rishis and saints from mystical traditions, and it’s so fantastic that we have found so many of our dreams, nightmares, and paradoxes. The things that we thought pertained just to the life of the mind in matter, I think is just, and also because of the feeling that we’re all, I think that this notion that we don’t understand the world is something that affects us all. And to me it’s painful because I was obsessed with understanding. I was one of those idiots who thought he could understand it all. Really. I know it sounds so stupid, but there weren’t that many books when I was growing up and I thought you could read them all. Really? How did we make these beings be half smart? Well, they just read everything we ever wrote.

Laurie Anderson:

Well, the thing about this also books now is, I mean, for example, this Bible that we produced was different. Every millisecond that you would print it, which I find really fantastic, it’s not just like you print it and that’s it. The Bible that they produced for me was they put everything that I’d ever written, said, or recorded, and they crossed it with the Bible, and then they sent me this 9,000 page edition of the Bible, according to me.

Benjamín Labatut:

But discrimination, right? I mean it really, not to sound like The Matrix, but it’s about choice. No, your art is really choice. Writing is just choice, and they don’t have the capacity to do that. They average it out. They tend to choose. Really, I have not been able to produce any text that’s worthwhile with AI so far, and I’ve used them a lot and I’m like, because it’s doing exactly what you don’t want to do. You want to take it in a different direction.

Laurie Anderson:

Depends on which thing you’re working with. I think mean predictive stuff is really, really boring. I really resent knowing what the next word is supposed to be. And I won’t just say swamp instead of swat. It’s just so pedantic.

Benjamín Labatut:

Yeah. But I think all of these things, the excess ity that we’re dealing with is one of the reasons why we don’t understand the world. There is such an excess at the moment, and I think that we are forgetting that one of the key drives of every single human being has to do with longing. And you can only long for the past or the future. There’s no longing for the present. There’s nothing, and we are kind of being compressed. People are unmoored. They don’t really have that sort of long tail backwards. We are living being kind of impoverished.

Laurie Anderson:

It’s very future oriented.

Benjamín Labatut:

I think it’s present oriented. Everything about it is becoming instantaneous. When we are creating so much so fast that we’re being squeezed into a moment, we’re being pressed. I think there’s also because of the speed of change, it’s like a fog’s come down.

Laurie Anderson:

I don’t know. I don’t get the sense that people are very much in the present at all. Very, very few people I know are actually right there in the present. Most are thinking of the future and the future isn’t what it used to be.

Benjamín Labatut:

Yeah, no, I know. The fact that we don’t inhabit the present is where our richness comes from. We are this sort of time making, manipulate, manipulating thing. I would leave the present for the bodhisattvas. There are very few of them that can stay there for us. We don’t live like that. We are stretched out, we’re pulled. And that pulling is really, to me, what gives life. It’s meaning that you’re being pulled towards something or you are, I know that I’m saying these things as the Rubinn, so kind of contradicting the major tenors of philosophy that is very, very dear to my heart. But as a writer, you work with the pool. That’s what you do.

Laurie Anderson:

Otherwise there’s no page turning.

Benjamín Labatut:

As a writer, you can consider all ideas, not just the ones that are true or even there’s this idea of the eschaton, the fact that there’s some sort of perfect being at the end of time and it’s pulling us towards it. Not just that we are traveling towards something, but we’re being pulled at. It’s an idea that I think comes from gnosticism and I think it’s beautiful. We have these notions that we’ve lost because we consider them irrational, but I think so many things suddenly become understandable when you consider irrational beliefs, when you consider ideas that are mad like Philip K. Dick’s,

Laurie Anderson:

Does the end of time count as that?

Benjamín Labatut:

The end of time

Laurie Anderson:

That was a phrase just

Benjamín Labatut:

I dunno, it’s there. It’s called the eschaton, and it’s kind of an object at the end of time pulling us towards it. I guess when I stopped believing that there was such a thing as a truth that I could get at through books, then you realize if it’s not a path forward, because it’s not like science where there’s a method, there was this sort of interchangeable. You could step into these mystical ideas and wander around in there and step out. It’s like a little controlled psychosis. And to me, that has been, that’s the sort of method I use for writing.

Laurie Anderson:

And this is sort of forward. You feel you’re being pulled forward somehow.

Benjamín Labatut:

It’s a particular energy that you don’t necessarily pray to. You just imagine. Again, it comes from gnosticism and it was very important to Philip K. Dick. He wrote a lot about that, and it’s where we get eschatology and all of these things. It’s a Christian concept. I think it’s an old Christian concept that we’re being pulled towards perfection and these things that are, they’ve just dropped out of our minds. We don’t see, we don’t even consider that this could be true. And I’m not saying it’s true. I’m saying it’s interesting. Keeps you alive.

Laurie Anderson:

Also, it is kind of obvious in many ways in terms of being pulled towards complexity. I mean, we are going generally in that direction where we’re becoming more and more complex. We’re not sliding down the other way to the evolutionary scale, becoming slowly slime and then slowly one cell creatures. We’re going the other way. It’s another way that we’re going. So I think that maybe is part of the idea of that we’re going towards something light in the future. Although I don’t think I see time that way anymore.

Benjamín Labatut:

I usually only pay attention to time when I’m reading about it. I think one of my favorite writers is here. Do we have time to read a little thing that’s not from me?

Laurie Anderson:

Sure.

Benjamín Labatut:

This is something that everybody has to read. It’s from Eliot Weinberger. It comes from, I think it’s from An Elemental Thing, and this is like, it’s about a Taoist concept of time. It’s called The Hidden Span.

The Taoist universe is an infinity of nested cycles of time, each revolving at a different pace, and those who are not mere mortals pertain to different cycles. Certain teachings take 400 years to transmit from sage to student, others 4,000, others, 40,000. It is said that Lao Tzu, the author of the Tao Te Ching, spent 81 years in the womb. Tao’s ritual begins with a construction of an altar that is a calendar and a map of the universe at its perimeter, 24 pickets, the 24 energy nodes each representing 15 days form of year of 360 days, three energies, the three rational powers, the five elements, the five tones, the six rectors, the eight trigrams, and the 64 hexagrams of the I Ching, the nine palaces and the nine holes. And then he says, typically of Taoism, the system has an inherent flaw, a hole in time called the irrational opening. If at a certain moment, which is always changing, one walks backwards through the various gates in a certain order, one can escape time and enter the hidden span in this other time beyond all the other times, one finds oneself in the holy mountains. There one can gather healing herbs, magic mushrooms, and elixirs that bring immortality.

I mean, these are just instructions for writing, right? We should live this way.

Laurie Anderson:

It’s map.

Benjamín Labatut:

When you walk. I’m sure there’s a bunch of hidden spans in New York.

Benjamín Labatut:

You just have to walk backwards.

Laurie Anderson:

Absolutely.

Benjamín Labatut:

Yeah. I think we’ve done a great job of getting people to be mindful.

Benjamín Labatut:

People to be…oh, come on. You can’t take two steps without meeting someone in yoga pants.

Laurie Anderson:

And that’s what I’m saying. That’s what I’m saying.

Benjamín Labatut:

But also, but how many of them practice Vajrayana? How many of them?

Laurie Anderson:

Not a lot.

Benjamín Labatut:

Yeah. So Buddhism itself, it goes towards Zen and we all like that because it’s very rational and ordered and pretty. But then who has ever hallucinated the gods of the Holy Mountains and then their demonic aspects? So I’m kind of saying that literature as an art form deals with the devil all the time. It’s like a constant, that’s what you do. It’s not about let’s leave Superman to the comic books. We like our monsters, we shape our monsters because those, every time there’s a monster, a monster is calling out for a hero. So there is this monster, there’s a bunch of them now.

Laurie Anderson:

Okay, so let’s say we call this orange guy a monster, and what is your hero that’s going to go and be create another, or let’s say you’re writing that.

Benjamín Labatut:

I think it’s a call for everybody to get in touch with their hero thing. I think we kind of lost track of that. We’ve become either half enlightened or lazy. We really rip the spirit out of everything, and we feel so cynical about our own spiritual development. We just see our flaws all the time. So it’s like, oh yeah, the hero journey was great for Joseph Campbell in the 70s. And it’s not like that. In dark times when the monsters rear their heads, that is the moment where you’re called to be a hero and you might just be a hero to your daughter. There is a call for meaning. There is a need for meaning to come back. We have both in science and in spirituality, reached these sort of levels of highly nihilistic enlightenment where you get to a point where you’re like, well, the only reasonable thing is to shut up.

Laurie Anderson:

Exactly. And actually I’ve been in that situation in the last couple months. That was the most reasonable thing to do. Unfortunately, that kind of freedom is to free each person to be able to say that’s true, and that isn’t because there’s so much pressure to say that the opposite is true. And it’s obviously who’s getting to tell the story? Who says what about what’s happening and who gets to build their museum?

Benjamín Labatut:

And the great game of opposite is the oldest game we play.

That’s why I think art and in particular literature is a great vehicle for paradox. It’s like if they are just like in a scientific experiment when you’re doing writing, you should want your reader’s brain to be in a superposition where he doesn’t really understand completely, doesn’t really know how he’s supposed to feel about it. And that sort of uncertainty is the highest form I think, of wisdom that we can, just getting used to the uncertainty, very useful for a moment like this, the one we’re going through, there’s nothing worse than a blissed out writer. Nothing really. But I know all jokes aside, if you want to write longing is fundamental because you’re basically saying, listen, I’m not leaving people behind. I am suffering just like any other idiot. And it’s very important to be idiotic and full of pain. Not necessarily childish suffering, but it is. When I practiced Buddhism, when I did meditation, my head was on fire. And I think that’s the right moment to meditate. Otherwise you’re just relaxing. But then it was like, okay, if I follow this thing, where is it going? And I know where it was going, and that’s always been a pull for me. You either kind of stay on the side of words or you go towards a silence and it’s very attractive, the idea to never write again. Do you have a wish? I’m bad with wishes.

Laurie Anderson:

A wish. Let’s see. It would probably have something to do with being able to stop time and just to have it experienced really fully in the present. I mean, that’s the only way I know how to relax now is to just empty my mind and be nothing. One of the motivations for this series that I was doing, I was in a very long meditation and 10 days where you meditate many, many hours a day. And I came out of that and was still in. I saw this kind of huge, I realized that I’d forgotten my name, and I was like, first I thought, that’s weird. I can’t remember my name. Then it was a little bit odder, and then I started to get worried, like, no, I really can’t remember my name. And then I’m thinking, do I have my name on a piece of paper that I have somewhere?

And this went on a very long time, much longer than, well, probably it was only about 20 seconds, but 20 seconds is really long. It’s not like when you’re introducing two people, you’ve obviously forgotten their names. So you go, you two should really meet. You’ve done a lot in common. So I really couldn’t remember and I couldn’t remember, and then I still couldn’t remember. And then I sort of came up out of that and saw this whole landscape of what I would describe as discarded thoughts. And this is of course, if the whole exercise of the mind is a blank sky and thoughts are clouds, get rid of them, let ’em go. So this was a landscape of that, and I was like, whoa. Just went on forever. And then I saw this very, sorry, it feels like I’m telling you my dreams.

Benjamín Labatut:

But people came here for that, Laurie, so please continue.

Laurie Anderson:

No, I saw this very, had a very shabby banner and it had my name on it and capital letters. I was like, how stupid is that? What does that have to do with this discarded landscape of discarded thoughts? And I thought, oh, finally, I’m making a little bit of progress. Because it was a really wonderful feeling to be there at that moment without being anyone at all.

Tim McHenry:

Thank you for listening to About Time. If you liked this program, you’ll enjoy the Rubin’s AWAKEN podcast which explores the dynamic path to enlightenment. Listen wherever you get your podcasts or online at rubinmuseum.org. And be sure to follow us on social media @rubinmuseum.

Please also consider supporting the Museum’s global mission to present Himalayan art and its insights by becoming a Friend of the Rubin at rubinmuseum.org/friends.

About Time was supported, in part, by public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, in partnership with the City Council.

About Time was made possible by the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of the Office of Governor Kathy Hochul and the New York State Legislature.

And until next time.

Do you feel like you’re running out of time? Which way is it going? Are you able to stop time? If so, how? Many objects in the Rubin’s collection of Himalayan art reflect the Buddhist concept of time, including the interconnected nature of the past and future. About Time aims to reframe our perspective on time and its impact on our lives.

Performance artist, electronic music pioneer, and filmmaker Laurie Anderson invited a group of her favorite writers, thinkers, and poets to tackle the big questions about time. In a lively discussion that covers everything from déjà vu to Dune, Laurie and novelist Benjamín Labatut explore the concept of what is real and what is not. This conversation took place in-person at the Rubin’s former 150 West 17th Street building in 2024.

Laurie Anderson is one of America’s most renowned and daring creative pioneers. She is best known for her multimedia presentations and innovative use of technology. As writer, director, visual artist, and vocalist she has created groundbreaking works that span the worlds of art, theater, and experimental music. Ms. Anderson has published seven books, and her visual work has been presented in major museums around the world. In 2002 she was appointed the first artist-in-residence of NASA, which culminated in her 2004 touring solo performance The End of the Moon. Her film Heart of a Dog was chosen as an official selection of the 2015 Venice and Toronto Film Festivals and received a special screening at the Rubin Museum, where she joined in conversation with Darren Aronofsky. Ms. Anderson has made many appearances at the Rubin, and has been in conversation with Wim Wenders, Mark Morris, Janna Levin, Gavin Schmidt, Neil Gaiman, and Tiokasin Ghosthorse. She also hosted the premiere season of the Rubin’s AWAKEN podcast.

Benjamín Labatut is a Chilean fiction writer whose English-language debut When We Cease to Understand the World seeks to understand the minds of physicists and mathematicians. His latest work of fiction The MANIAC centers on John von Neumann whose discoveries laid the groundwork for computer science and nuclear weapons.

Tim McHenry is a founding Rubin staff member and was in charge of programs at the Museum for its first 20 years. He specializes in art-contextual experiences that break the traditional mold, presenting audiences with what the Huffington Post has called “some of the most original and inspired programs on the arts and consciousness in New York City.”

McHenry’s public programs have explored the wider implications of the Rubin’s objects and collection of Himalayan art through music, film, performance, immersive engagement, and intimate conversation. He is the curator of the Mandala Lab, now on view in a free-standing version that has traveled to Bilbao, London, and Milan.

Get the latest news and stories from the Rubin, plus occasional information on how to support our work.