Courtesy of Karl Ryavec

Courtesy of Karl Ryavec

In the era of Wikipedia and Google, maps are more ubiquitous than ever and often taken for granted. It’s assumed that the most up-to-date information on streets, neighborhoods, and points of interest can all be found with the tap of a finger. However, if you’re in search of a map that shows how things once were, where would you start?

Karl E. Ryavec, professor of world heritage at the University of California, Merced, faces the daunting task of mapping Lhasa—the historic capital of Tibet—which has transformed over the years through various imperial reigns and interactions with other civilizations. His unique atlas is the first of its kind to combine a series of 49 color maps, essays, and photographs that illustrate the historical growth and spread of Tibetan civilization across the Tibetan Plateau and surrounding regions from prehistoric times to the present. But there are still questions that Ryavec and his colleagues have yet to answer.

Read on to learn about Ryavec’s process of mapping the ancient capital while authoring A Historical Atlas of Tibet.

When I started making A Historical Atlas of Tibet in 2005, I realized I would need to make some maps of Lhasa to show the details of the many important cultural and religious sites in the city and surrounding valley. Since there already was an atlas focused on the city (Knud Larsen and Amund Sinding-Larsen, The Lhasa Atlas, 2001), I knew I could save time and effort by making small insets of Lhasa to include on each main map of central Tibet to show the key sites built during each historical period. Still, there is room for me to revise and expand my atlas to include much more detailed historical maps of Lhasa in the future.

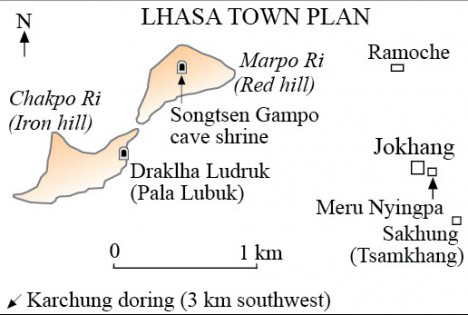

I started with the Imperial period, ca. 600–900, to map the earliest important sites in the core area of the city, namely the Jokhang and Ramoche Buddhist temples. A perusal of the available site surveys and scholarship also documented several other temples nearby, along with two sacred cave shrines on Chakpo Ri (Iron Hill) and Marpo Ri (Red Hill). As seen in a copy of my small Lhasa inset map below, the spatial patterns show how the Jokhang Temple helped form an early center to the city, with several of the other temples clustering around it.

Courtesy of Karl Ryavec

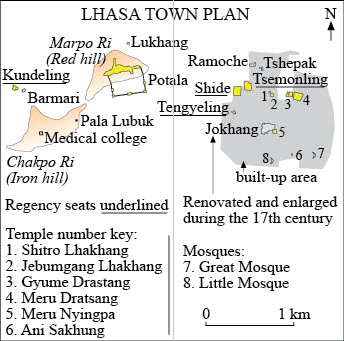

Over the following centuries, after the collapse of the Tibetan Empire, a long period of political disunion prevailed across Tibet from ca. 900 to 1642, during which only about four more temples were built in the central city. It is also important to realize that Lhasa itself was never a capital city during these times. Under the empire, the royal court (Pho brang) moved seasonally in a large tent encampment, hosted by different clans based in different areas of central Tibet. Though the royal court never camped in Lhasa itself according to the available sources, the council met there at times. Overall, from ca. 600 to 1642, there was never any strong sectarian presence in Lhasa even though the political history of Tibet after ca. 1000 largely reflected the activities of the main schools and sects of Tibetan Buddhism. Almost all of the temples built in Lhasa prior to the 17th century were non-sectarian establishments.

Lhasa changed considerably with the rise of the new Ganden Podrang (Kingdom of the Dalai Lamas) government after 1642. Now for the first time the city took on a specific Buddhist sectarian identity—that of the Gelukpa or reformed sect—often called the Yellow Hats. Here I mapped the largely new constructions of this period with a yellow color to indicate these sectarian establishments. Two patterns are most striking: the new Potala Palace dominating the cityscape from atop Marpo Ri, and the large regency seats mostly built in the old city center.

Courtesy of Karl Ryavec

One question I’ve always wondered about is whether Lhasa ever had any city walls, at least during some war-torn periods prior to 1642. We know that the chorten (stupa) built in the gap between Chakpo Ri and Marpo Ri functioned as a sort of gate for travelers arriving from India and the West during more recent times. But what about other points of entry? Perhaps the sacred circumambulation path around the city, the Lingkhor, also functioned as a sort of boundary with minor house walls and gates protecting the older, built-up part of the city.

Get the latest news and stories from the Rubin, plus occasional information on how to support our work.