Tenzin Gyurmey Dorjee at work in his studio; photo courtesy the artist

Tenzin Gyurmey Dorjee at work in his studio; photo courtesy the artist

My family comes from a lineage of Tibetan Buddhist practitioners, with my grandfather having a history of Vajrayana, or Tibetan tantric, practice. During my childhood, my father shared many tantric stories with me—some based on real-life experiences, others personal accounts, and some mythological. One story he shared was about the creation of a kang ling, a ritual trumpet crafted from a human femur and traditionally used in tantric practices. Such stories were both fascinating and taboo to me. I had never seen a kang ling in real life.

It wasn’t until my school days, when I was newly introduced to the internet, that I stumbled upon an image of a kang ling on the Rubin Museum’s website. This discovery was profound—it brought to life the stories my father had told me and allowed me to visually connect with an object that had seemed almost mythical. From then on, I relied on the Rubin’s collection whenever I needed references for my father’s stories.

Leg Bone Trumpet (Kang Ling); Tibet; 18th-19th century; Human bone, copper, coral, leather; Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art, Gift of Robert and Lois Bayils; SC2019.3.2

Similarly, my father also spoke about a thangka of Palden Lhamo holding a sword with a scorpion-shaped handle, which he had read about in the book The Hidden Life of the Sixth Dalai Lama. Such a thangka has always felt like a mystery to us, as we’ve never seen one in real life. The idea of it, though, reflects the deep symbolic and esoteric meanings that such artifacts carry, many of which remain unseen or hidden even within Tibetan communities.

My experience highlights the importance of museums preserving and making visible cultural objects that might otherwise remain hidden. In Tibet, such items are rarely shown publicly, often kept secret, passed down quietly, or sold. Museums have the unique ability to not only safeguard these objects but also to provide access to them in a way that invites study and engagement. For me, the Rubin Museum has become an invaluable resource, offering a bridge to my family’s heritage and helping me deepen my understanding of the cultural narratives that shape my identity.

With this personal history in mind, when I heard that the Rubin Museum returned a 14th-century wooden carving of a garland-bearing apsara to Nepal in January 2022, I was both intrigued and surprised. In a world where institutions often inherit complex histories tied to colonization, unequal exchanges, and art objects without a clear provenance, the Rubin Museum’s decision stands as an example of how organizations can actively engage with these challenges. It reminded me that true progress often requires self-reflection, humility, and the willingness to make things right, even when it is not easy.

One of my early works, Morning Resolution, explores this very idea: the necessity of confronting challenges instead of running away from them. In the painting, I wanted to capture the transformative power of perseverance and self-awareness. Too often, we shy away from our responsibilities or blame others for the difficulties we face. This avoidance not only stunts our growth but also prevents us from developing the resilience and wisdom needed to navigate life as human beings.

Tenzin Gyurmey Dorjee; Morning Resolution; acrylic on tarp; image courtesy the artist

We are meant to make mistakes; it’s part of our nature. What defines us is not our perfection but our willingness to learn from those mistakes and use them to guide future generations. The inability to take responsibility—for own our flaws and failures—impedes both personal and societal progress. If we only point fingers at others, refusing to examine ourselves honestly, we miss the opportunity to grow as individuals and as a collective.

These reflections became the foundation of my artistic practice, where I strive to explore themes of accountability, growth, and cultural belonging.

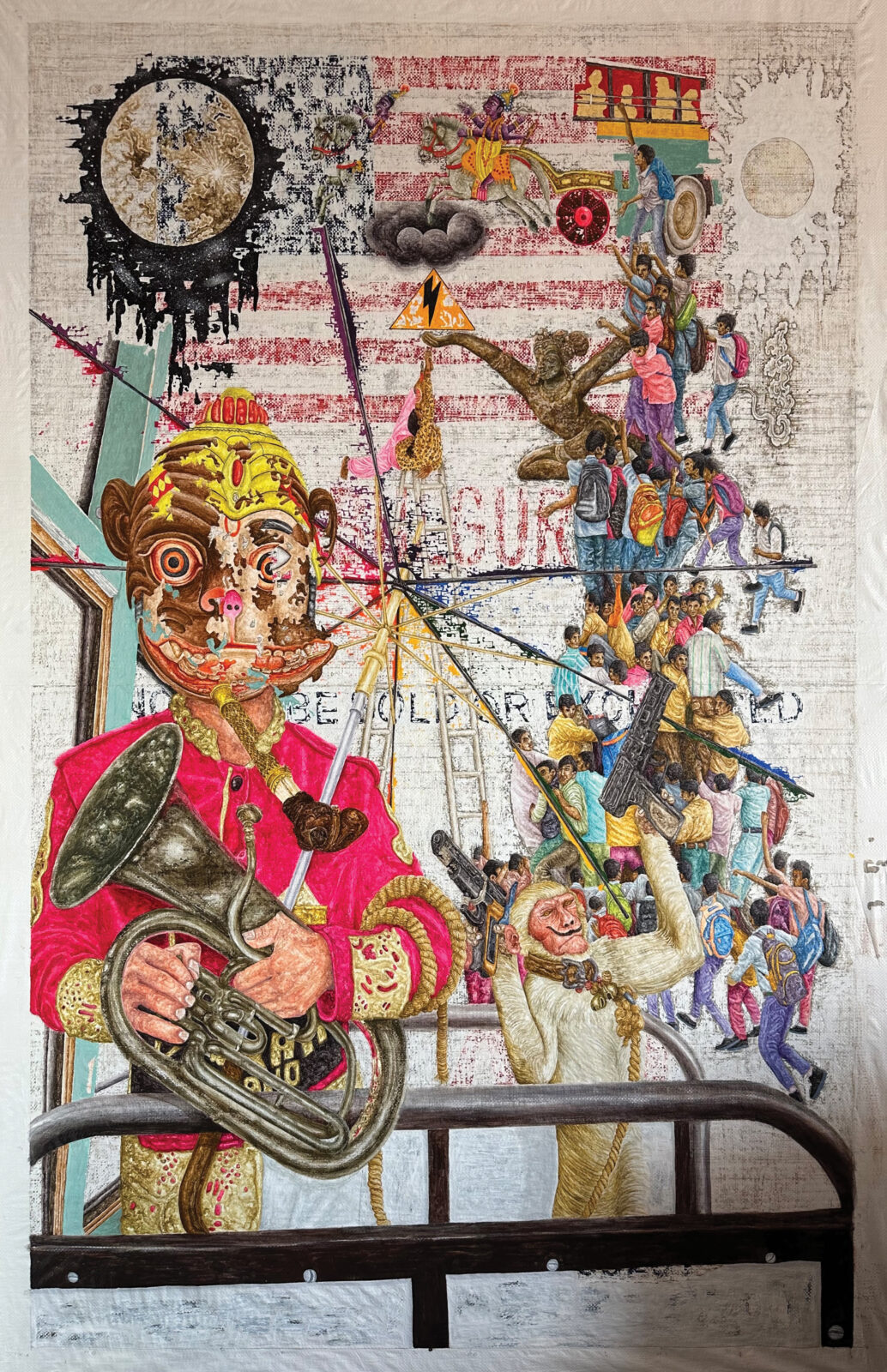

These themes were central to the painting chants of a monkey mind, created for the Rubin’s exhibition Reimagine: Himalayan Art Now, which garnered me the Rubin Museum Himalayan Art Prize. This work was inspired by the complexities of human existence, particularly the tension between chaos and grace, ambition and compassion.

Tenzin Gyurmey Dorjee; chants of a monkey mind; 2023; acrylic on tarp; Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art; C2024.1.1

The painting features an apsara—a celestial being symbolizing beauty and transcendence—emerging from a mountain of crowded male figures. These figures represent the relentless energy of human life: daily workers, college students, businessmen, performers, and commuters all climb over each other in their pursuit of success, survival, and purpose. Their movements are chaotic, almost frenzied, echoing the busyness of a packed morning bus or bustling street corner.

At the top of the mountain, a figure unleashes a thunderstorm, a metaphor for the destructive tendencies that arise when ambition is unchecked and disconnected from wisdom. In contrast, the apsara at the center of the composition offers a moment of calm and clarity. She reaches out her hand in a protective gesture, shielding a small girl from the storm above. This act of protection is not just an act of grace but a reminder of the responsibility we carry for the next generation.

In the apsara’s gesture, I wanted to capture the same spirit of accountability and care that inspired me when I learned about the Rubin Museum’s return of the apsara carving to Nepal. Her presence amid the chaos serves as a symbol of hope and an invitation to find harmony even in the most overwhelming circumstances.

The crowded male figures in chants of a monkey mind also symbolize the struggles of modern life—our tendency to get caught up in material pursuits, social pressures, and the never-ending race for success. Like the “monkey mind” in Buddhist teachings, which refers to the restless, unsettled state of our thoughts, these figures reflect the distractions and anxieties that often dominate our lives.

Yet the apsara’s presence suggests that even amid this chaos, there is the potential for transformation. Her emergence from the mountain signifies the possibility of rising above our fears, insecurities, and distractions to connect with something deeper—our shared humanity and capacity for compassion.

This journey from chaos to wisdom is not easy. It requires facing uncomfortable truths about ourselves and the world around us.

This journey from chaos to wisdom is not easy. It requires facing uncomfortable truths about ourselves and the world around us. It demands that we take responsibility for our actions, even when it is easier to blame others. But it is through this process of introspection and accountability that we find our true selves and contribute to the collective progress of humanity.

For me, art is not just a form of expression but a way of engaging with the world’s complexities and contradictions. It is a medium through which I can explore questions of identity, responsibility, and belonging.

The act of restitution exemplifies the kind of values I hope to reflect in my own work: respect for cultural heritage, a willingness to confront difficult histories, and a commitment to doing what is right, even when it is challenging. Such moments remind us that institutions, like individuals, have a responsibility to learn from past mistakes and take meaningful steps toward accountability and justice. It also also highlights the power of transparency and openness in fostering trust.

Tenzin Gyurmey Dorjee at work in his studio; photo courtesy the artist

As I reflect on these themes, I am reminded of the interconnectedness of our actions and the impact they have on the world around us. Whether as individuals, communities, or institutions, we all have a role to play in creating a more just and compassionate society.

The apsara in chants of a monkey mind is not just a celestial figure; she is a symbol of the grace and wisdom that lie within all of us. Her gesture of protection is a reminder that we have the power to care for one another, rise above our challenges, and create a world where future generations can thrive.

Through my own work, I hope to continue exploring these themes and contributing to the ongoing dialogue about accountability, growth, and the human journey. Like the apsara, we too can find moments of grace amid the chaos, and in doing so, we can inspire others to do the same.

Tenzin Gyurmey Dorjee at work in his studio; video courtesy the artist

Tenzin Gyurmey Dorjee was born in 1987 in Kamrao Village, Himachal Pradesh, India. He is interested in exploring the paradoxes present in ordinary things and how global changes in culture, politics, climate, and science can impact local surroundings. His father, Tulku Troegyal, taught him drawing in the Tibetan traditional style at the age of six, and he has been practicing arts professionally since 2013. His studio practice is currently based in Delhi.

Get the latest news and stories from the Rubin, plus occasional information on how to support our work.