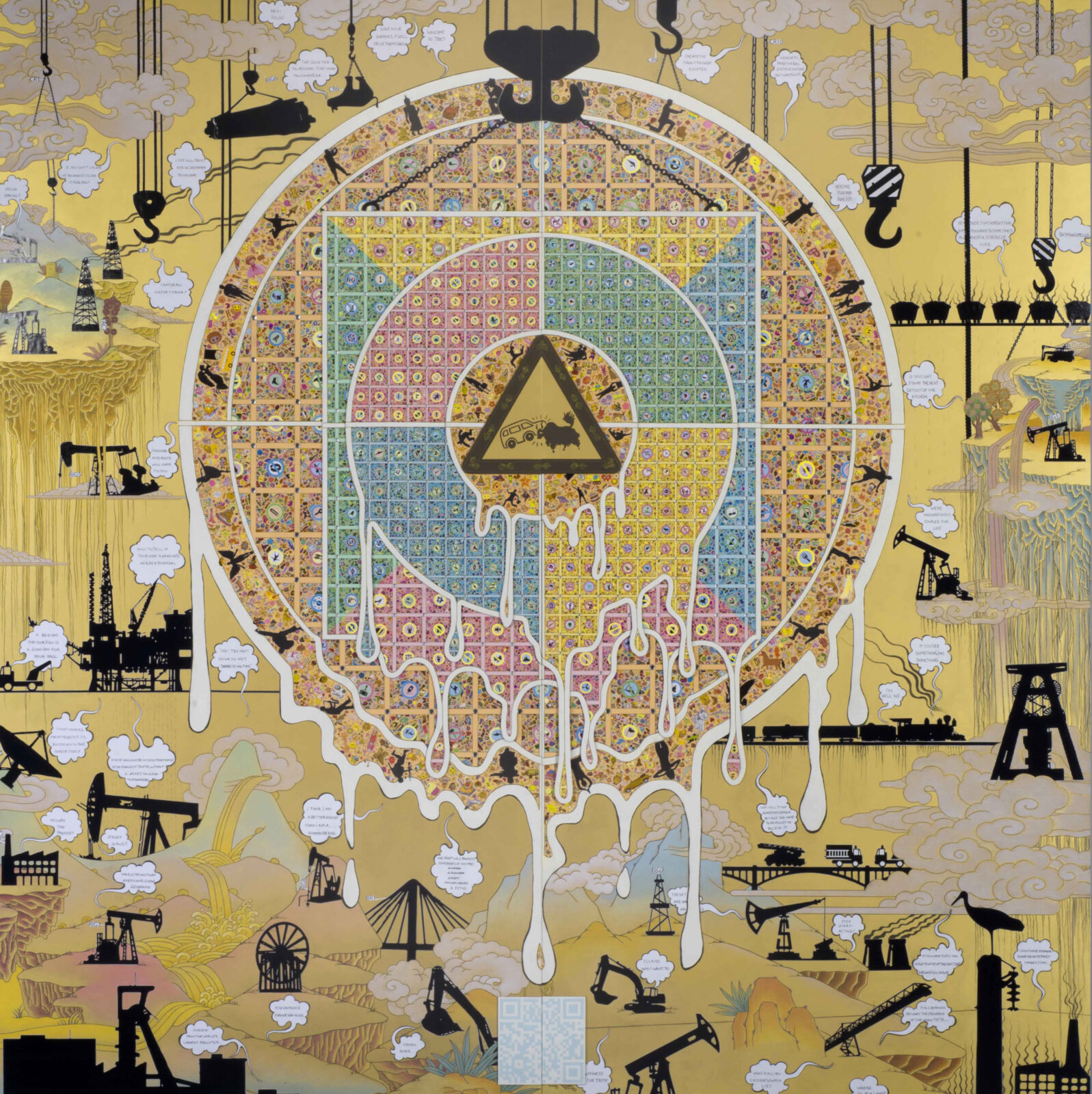

Illustration by Gonkar Gyatso

Illustration by Gonkar Gyatso

In 2009, I lost my faith in politicians, governments, and the private sector to ever “fix” the environmental and climate crisis. I watched a “yes we can” president distance himself from progressives, witnessed the death of the American Clean Energy and Security Act on the Senate floor (it would take fourteen years for another US bill on climate change to be introduced), and lived through the ignominious collapse of the Fifteenth Convention of Parties led by the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change in Copenhagen, largely engineered by the United States, China, and other industrialized countries.

Before then, it was obvious to me that neoliberalism (extreme capitalism with no checks or balances) and its growth-at-all-costs agenda was fueling the environmental and climate crises. By the end of 2009, I came to accept that this global economic system allowed politicians, governments, and the private sector to profit so greatly from environmental and climate devastation that they were, in fact, disincentivized to stop it.

I was devastated. It is hard to explain how traumatic a crisis of faith is to people who may not share that experience with you. I had been an environmentalist since I was fifteen and had worked for mainstream environmental organizations for over a decade at that point. Suddenly, there I was, questioning every decision made by the movement I belonged to. Trying to make sense of it all, I wrapped myself up in my community, spent time with senior Tibetan Buddhist monks and nuns, went wandering in wilderness areas, consulted endlessly with friends and mentors, and revisited my favorite thinkers and writers (Walden Bello, Vine Deloria Jr., bell hooks, Audre Lorde, and Vandana Shiva, to name a few).

Sometimes a crisis of faith is necessary for us to wake up and choose a new path.

Sometimes a crisis of faith is necessary for us to wake up and choose a new path, even one that is littered with major obstacles, confusing trail signs, or no signs at all. In my case, I chose faith. Not only my own faith but also those representing over eighty percent of the human population. I convinced the World Wildlife Fund to let me work with world religions in priority conservation landscapes. I expanded Khoryug, a project I had created in 2008 to help Tibetan Buddhist monasteries and nunneries in the Himalayas lead local environmental protection projects under the auspices of His Holiness the Karmapa, and began working with Buddhists in Cambodia and Thailand. I launched a new program called Sacred Earth and built partnerships with the Catholic Church, Indigenous leaders, Muslim clerics, and Evangelical preachers in the Amazon, East Africa, and United States on conservation and climate issues. It was the saving of me and the making of what is now the Loka Initiative, an education and outreach platform at the University of Wisconsin–Madison that supports faith-led environmental and climate efforts locally and around the world.

The simple truth is that economic growth is incompatible with a living planet. Neoliberalism, which has dominated the world for over fifty years, props up a tiny sliver of a fraction of the human population to hoard the vast majority of resources and power. The truth is the gap between the rich and the poor has never been so stark: since 2020, the richest one percent has taken possession of nearly two thirds of all new wealth, worth forty-two trillion USD. The truth is that oligarchs will always tow us toward fascism, including political and social chaos, because it allows them to maintain and consolidate even more power than what they already have. And so here we are.

2024 was the hottest year on record. November 2024 was the sixteenth consecutive month where the global-average surface air temperature exceeded 2.7°F (1.5°C) above preindustrial levels. Keep in mind 1.5°C was supposed to be our maximum threshold for global warming; instead, it has become our new baseline. If there isn’t a drastic change now, we are headed toward 2.5°C global warming by the year 2100.

The problem and the miracle of our planet’s operating systems is that all of them are interdependent with each other.

That means we are now living in a time that is unprecedented in human history. This year and every year ahead will see a sharp irreversible increase in more frequent and intense climate related unnatural disasters. We are operating beyond what is safe for seven of the nine planetary boundaries—what are essentially the planet’s operating systems. Climate is only one of those operating systems that regulate the Earth. The problem and the miracle of our planet’s operating systems is that all of them are interdependent with each other. As one changes or collapses, it triggers a cascade of effects that we cannot entirely predict.

In the last fifty years, we have hemorrhaged seventy percent of vertebrate populations (mammals, birds, amphibians, reptiles and fish). We have released 350,000 different types of manufactured chemicals, including pesticides, microplastics, and industrial chemicals, much of which are unregulated, into every corner of the planet and every part of our own bodies. And our construction of largescale dams and other water technologies have so altered rivers, lakes, and streams that they are no longer able to regulate vital ecological and climatic freshwater processes.

The absolute truth is that we are in deep trouble.

How do we hold fast, attempting systems change at all levels, knowing what is barreling down upon us? How do we find the courage to keep striving? Here is the other absolute truth that keeps me going. It turns out that I am capable of losing faith in politicians, institutions, ideologies, and even movements, but never in the sacredness of the Earth herself. What is the Earth after all but the primordial and literal object of refuge for us all?

I come from a land and from a tradition where the people make prostrations as they circumambulate sacred mountains and lakes, taking refuge and purifying ourselves as we do so. And, in the act of taking refuge, we are taught to align our body with our mind and our spirit. Every meditation practice in Tibetan Buddhism shows us how. We begin each practice with the ritual of three prostrations. We prostrate to the outer objects of refuge of the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha; to the inner objects of refuge of the Lama, the Yidam, and the Khandro; and sometimes to the secret objects of refuge. We close each practice by dedicating its merit to the benefit of all sentient beings. Both of these acts emphasize an important aspect of meditation practice, maybe even the most important one: our meditation is not meant to be solely a cerebral or even spiritual practice—it has to be embodied to have meaning. Why call it practice other than to remind ourselves that it is a rehearsal for being tangibly in relationship with others?

When I think of the Earth, I am filled with awe. Behold this one tiny life-bearing miracle of a planet in the vastness of the universe, organizing every biological process around the principles of compassion and interdependence, birthing innumerable sanghas of life that collaborate in order to survive and thrive. What is the Earth if not the perfect embodiment of the three jewels: the enlightened one, the manifestation of the ultimate truth, and the body collective that strives toward both?

Through her arises all the conditions for life and through her, we breathe-eat-drink-wear-touch loving kindness and compassion. After all, she is Yum Chenmo, the Great Mother. Take a moment to look at the in-betweenness inside of you, the in-between space between you and your loved ones, the spaciousness between us and all living beings, and there she is, entwining us with the water, nitrogen, and carbon cycles, ensuring that our well-being is completely interdependent with everything else that exists upon this planet.

Losing faith is painful, even heartbreaking, but even that has value, because from it can emerge great wisdom

Losing faith is painful, even heartbreaking, but even that has value, because from it can emerge great wisdom. We are now at a point where we must lose our blind faith in capitalism and organize ourselves collectively around de-growth and circular economies. That means we will be up against neoliberal fascists and oligarchs who are even now hoarding power and control. It means we must build the courage to stand together from the Buddha ground up, literally for the sake of all sentient beings. It means we must embody all those principles we so deeply admire and cultivate and act upon them.

Ultimately, there is one lasting truth—we have but one Earth, she is our only refuge in the vast universe, and we are inseparable from her. What happens to her happens to us all. It is time to align our bodies with our minds and spirits and to show up tangibly and in relationship with others. The Great Mother is waiting, waiting for us to awaken.

Dekila Chungyalpa is the founding director of the Loka Initiative. She has 25 years of experience in global conservation and climate solutions, working on faith-led environmental and climate partnerships, biodiversity landscape and river basin management, community-based conservation and resilience. Dekila is the daughter of the late Tsunma Dechen Zangmo, a Buddhist nun and teacher from Sikkim, and belongs to the Karma Kagyu lineage of Tibetan Buddhism. She occasionally teaches meditation to address eco-anxiety and climate distress.

Gonkar Gyatso is a Tibetan-born British artist whose multimedia practice involves painting, sculpture, photographs, and installations. He spent his youth in Tibet, completed his art degree in Beijing, and taught art at Tibet University. In the 1980s he founded the first contemporary Tibetan art movement and group, the Sweet Tea House Group in Lhasa. In the late 1990s he journeyed to India to immerse himself in the study of Tibetan traditional painting and later secured a scholarship from London’s Central Saint Martins College of Art and Design. In 2003, he founded the Sweet Tea House Gallery in London. He currently works in Chengdu, China.

Get the latest news and stories from the Rubin, plus occasional information on how to support our work.