Bidhata K C; Out of Emptiness; 2023; metal cans; image courtesy of the artist

Bidhata K C; Out of Emptiness; 2023; metal cans; image courtesy of the artist

A Nepalese artist questions traditional cultural beliefs through installations featuring unexpected materials and contemporary twists

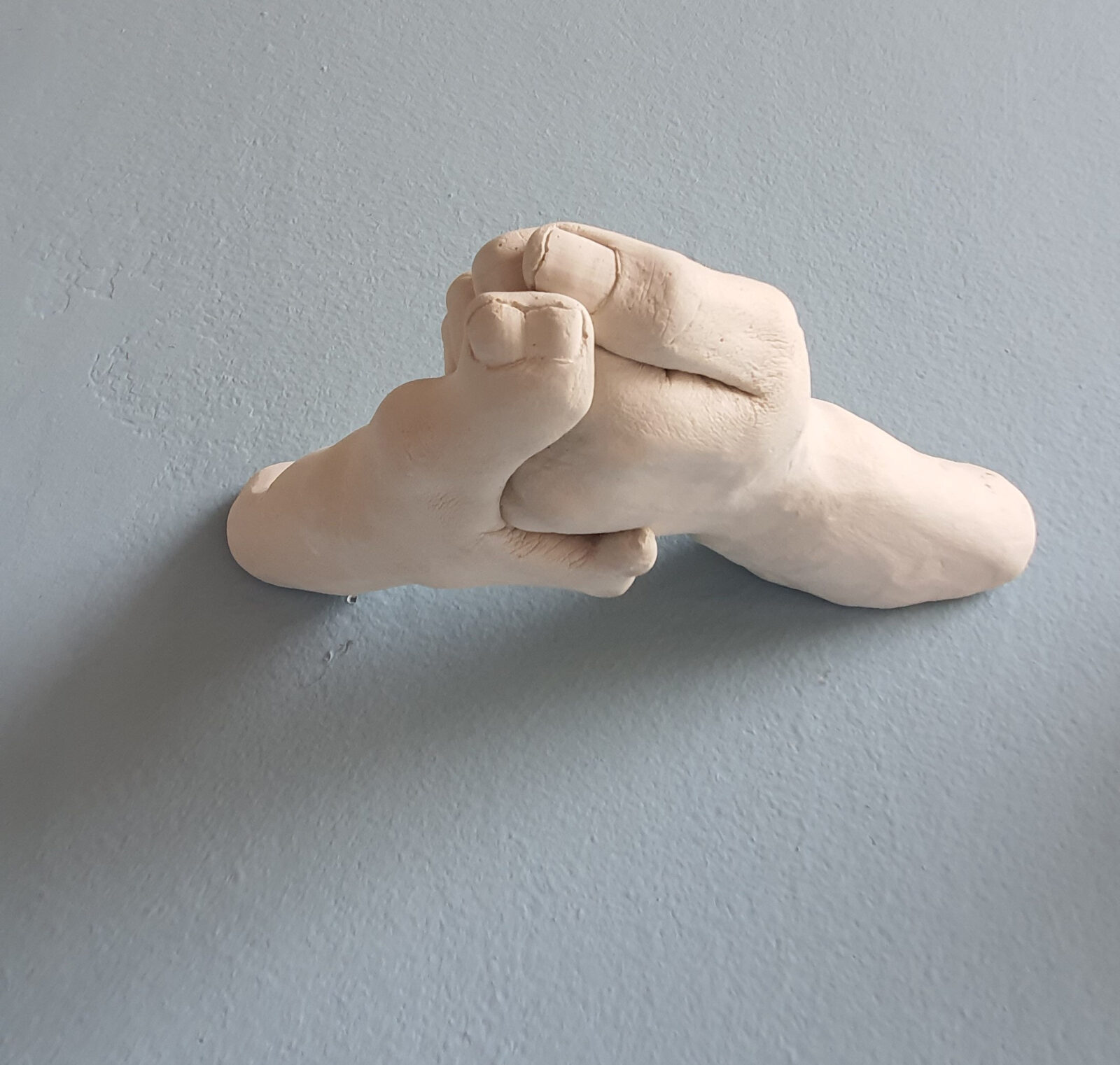

Bidhata K C; My Left Is My Right; 2022; installation; image courtesy of the artist

My work is mostly inspired by small things and the many layers and meanings in them. It can be with the material. My work has lots to do with the duality of a material and its identity, as well as how it interacts with us and how we give it multiple meanings and values. My work is also mostly about lived experience—what I have experienced. I’m into observing people’s conversations and taking out things from that. Not seeing facts but noticing even how a small word can impact a person.

My country is in a very transitional phase, so I try to explore the traditional motives and Western contemporary modern motives—how they’re coexisting and how we are trying to live in that. I try to create new narratives by bringing together modernity and the traditional in my work.

Out of Emptiness is also a new narrative of an old practice and a contemporary interpretation of a Buddhist prayer wheel. The inspiration is how one simple thing can have multiple meanings. A discarded object can be a valuable entity for us, and our need can change the meaning of a particular object. Because a tin can is just a container for us, and then it is discarded. It’s a cycle of one thing goes after another, and it becomes a totally different kind of repurposed object. At first, it’s just a container, and then we propose it being a valuable thing. This process also reveals our deep interdependence with the material world around us—how our relationships with objects, like with people, are constantly shifting and cocreated.

Prayer wheels have lots of mantras inside. When you spin it, you are supposed to pray all the mantras. But spinning these empty tin cans, without any mantras inside, still puts you in that space where you feel like you chanted all the mantras. That made me very curious—how a simple empty thing can give you such immense, powerful feelings.

Then when I got into the deeper level, I saw how culture is fluid; it’s not confined. The people who are from the high Himalayas are not exposed to modernism, but still they are adapting things thrown away by tourists. They take things like tin cans and create a different meaning by making prayer wheels with them. Out of Emptiness is also about looking at how unorganized our garbage system is in the high Himalayas and how it is becoming polluted.

It means the emptiness of the can. The crafted, decorative prayer wheels we see in temples are totally opposite to these empty cans. These cans are empty, yet the intention of this creation is to explore how that very emptiness can evoke a sense of fulfillment within us.

Bidhata K C; Out of Emptiness; 2023; metal cans; installation view of Reimagine: Himalayan Art Now presented by the Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art, March 15–October 6, 2024. Photo by David de Armas, courtesy of the Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art

Most of my works reflect on my lived experiences, which are rooted in cultural and social contexts. The installation Chori Manche Bhaera/Keti Manche Bhaera (being a girl and being a daughter) is one such example. These seemingly small phrases have a profound impact—they shape how you see yourself and how the world sees you. Your entire life can become tied to them. If you look back to childhood, these words were planted in your mind early on, embedding themselves in your subconscious. This work emerged from that lived experience, where I began to question: What if we were raised simply hearing, “Be a human”?

A few years ago my dad died. We have to do the 13 days of rituals. The patriarchal society of Nepal is strong, but being female and also being single, I was able to do all the rituals for my dad. But I can only use my left hand. In my culture, the right hand is considered pure, and the left hand is impure. Even though I fulfilled every ritual, I found myself questioning: Am I the right person to do this? What is the purpose of being who I am, if I can’t perform these rites according to cultural standards? Is there no space for someone like me—a left-handed person? From this experience I created the installation My Left Is Right.

I have done a lot on women’s cultural and social issues. I either have to live that experience or I have to really see and observe and embed it in me.

I cannot break through them, because they are so rooted in our society, but I want to say these things can change. There should be another way. You have to bring out the in-between ways.

I can never change this idea of the right hand being pure and the left hand being impure. It has to change within society. For me, it’s more about questioning culture through art and seeing how people accept it. But when I work, I never think about bringing awareness through my art. I feel I have to work on these things for myself.

When I put my work in front of the public, they can observe and interpret it in their own way. It’s not necessary to perceive it the way I do. I am interested to see how the multiple layers of meaning come from the different interpretations of my work.

Bidhata K C; My Left Is My Right; 2022; installation; image courtesy of the artist

I remember at the opening of Reimagine: Himalayan Art Now one woman was there dressed in traditional Tibetan attire. I didn’t interact with her, but I saw her wheel the tin cans and bow down. The tins are not crafted; there are no mantras in them. But still the interdependence of those objects together created a new life for them and a sense of belongingness within the space. Belief and faith were reinforcing their existence. That was interesting for me to see. It’s not about the idea but about how minimal things have such a huge impact.

Bidhata K C; Out of Emptiness; 2023; metal cans; installation view of Reimagine: Himalayan Art Now presented by the Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art, March 15–October 6, 2024. Photo by David de Armas, courtesy of the Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art

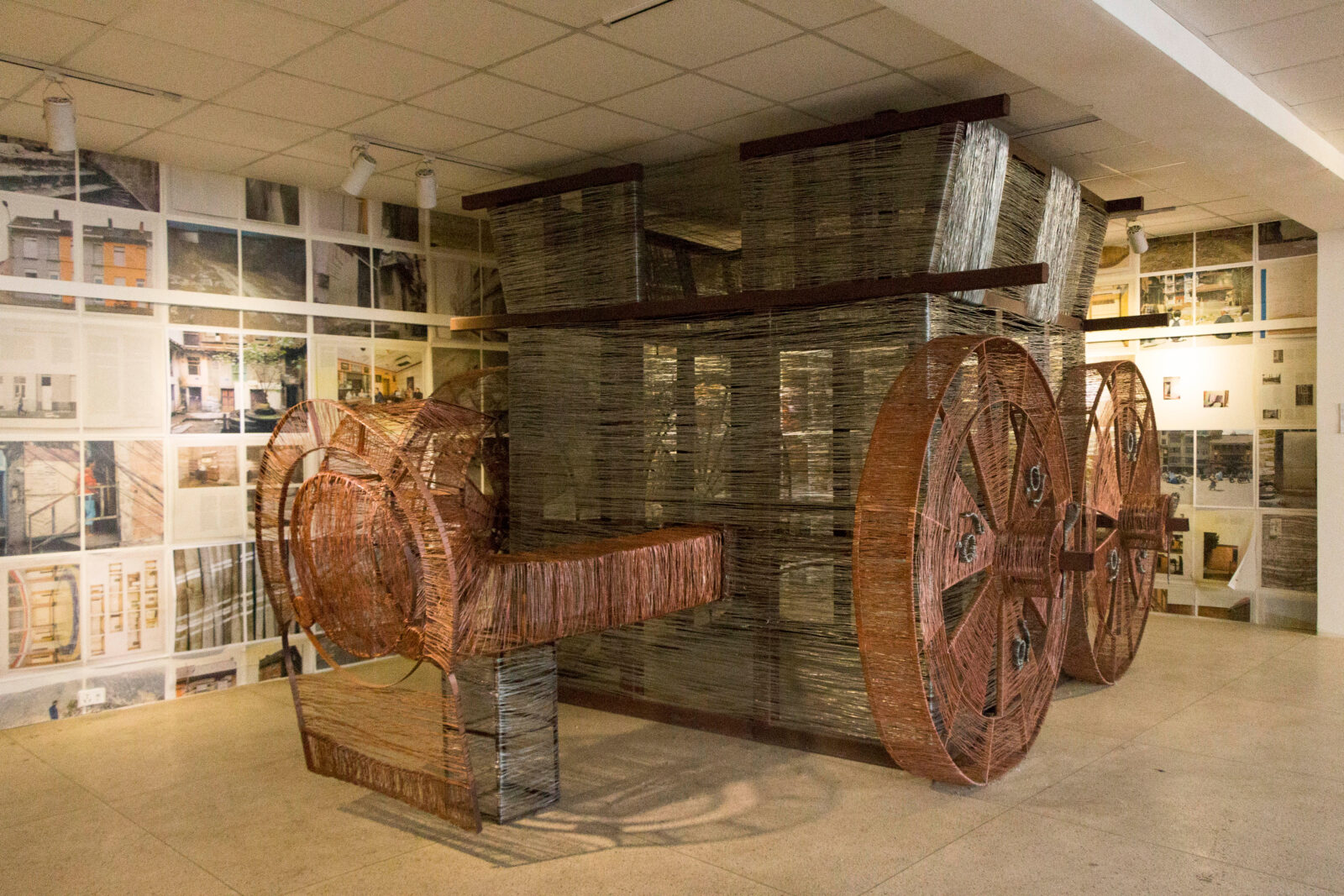

For In Between I created a chariot based on the ones used in the Rato Machindranath Jatra festival with contemporary materials, not with traditional materials—wood and straw—but with rods and wires. I tried to reimagine the chariot and explore how we contemporize other traditional values in our daily lives.

I created three parts of the chariot and put them on three different floors, trying to see how we are fitting in traditions into contemporary society, dividing these things up. I put the section with the wheels on the first floor, the temple where the god resides on the middle floor, and the top part with the cone on the third floor. One group of people who are blind came, and the person who brought them told me it was powerful because they could experience the work by touching it and feeling the textures of the wires.

Another woman told me even though it’s a contemporary work of art, In Between made her feel like she was inside the space where gods reside. I am in awe of that kind of thing, because I intentionally created the chariot in part so people can go inside and feel that spiritual vibe or whatever they feel. Usually it’s only the priest who can go inside, and it’s prohibited for females.

Bidhata K C; In Between (ground floor); 2017; interactive installation; image courtesy of the artist

Bidhata K C; In Between (middle floor); 2017; interactive installation; image courtesy of the artist

Bidhata K C; In Between (top floor); 2017; interactive installation; image courtesy of the artist

We are living in the present, and everything around us is impermanent. For me, the impermanence of art feels natural—it doesn’t need to last forever. Most of my installations are dismantled after the exhibition, and I’m completely at peace with that. Some things are meant to exist only for a certain moment in time. That transience gives the work its own meaning and presence.

Bidhata K C is a contemporary artist based in Nepal. Through installations, paintings, and prints, she primarily investigates issues of identity, material culture, and relations between the old and the new in our daily lives. Bidhata K C finds inspiration in the centuries-old artistic traditions of her native country to create striking images of contemporary narratives.

In 2011 her painting Marginalized Identity was recognized with the Special Mention Award at the National Fine Art Exhibition in Nepal. She was represented by the Nepal Art Council in the India Art Fair 2016, and she was one of the 15 commissioned artists for the 2017 Kathmandu Triennale. In 2018 Bidhata K C was honored as the Artist of the Year, 100 Most Influential Women of Nepal, and was a recipient of the Australian Himalayan Foundation Art Award. In 2022 she was selected by the US Department of State to attend the Social Change Through the Arts initiative under the International Visitor Leadership Program.

Sarah Zabrodski is the senior editor and publications manager at the Rubin Museum.

Get the latest news and stories from the Rubin, plus occasional information on how to support our work.