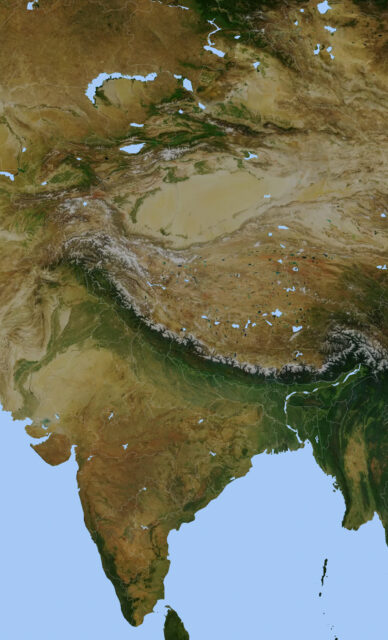

Art in Himalayan regions and culturally related areas of plays an important role in the everyday and religious life of the people. As part of the , , and cultures, images and ritual objects tie into symbolism, ritual, and daily cultural practices that shape, maintain, and help understand specific worldviews and permeate all levels of society.

Himalayan art is created and commissioned for specific purposes and various functions in cultural and religious practices that range from individual and family-centered to communal and even regional.

Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art, "Art and Religiouis Practice," YouTube, January 29, 2025, 3:40, https://youtu.be/Jc0ft4wGi9o.

Merit Permalink

One fundamental intention for commissioning a painting or sculpture, creating a large appliqué image, copying or printing a religious , carving a mantra in stone, pressing an image in clay, and so on, is to generate religious merit or positive karma for the future of an individual person as well as others. This includes commissions on behalf of a deceased family member, to honor a , or to remove obstacles in life or a religious path. Emperors, rulers, and heads of religious traditions also commissioned art, many on monumental scales. Temples and house numerous sculptures and their walls are decorated with murals. Sets of hanging scroll paintings commemorate teachers and inspire, instruct, and propagate religious tradition. Patrons and commissioned artists both gain from art production.

Handheld Prayer Wheel; Central Tibet; early 20th century; Silver, wood; Rubin Museum of Art, Gift of Shelley and Donald Rubin; SC2012.7.2

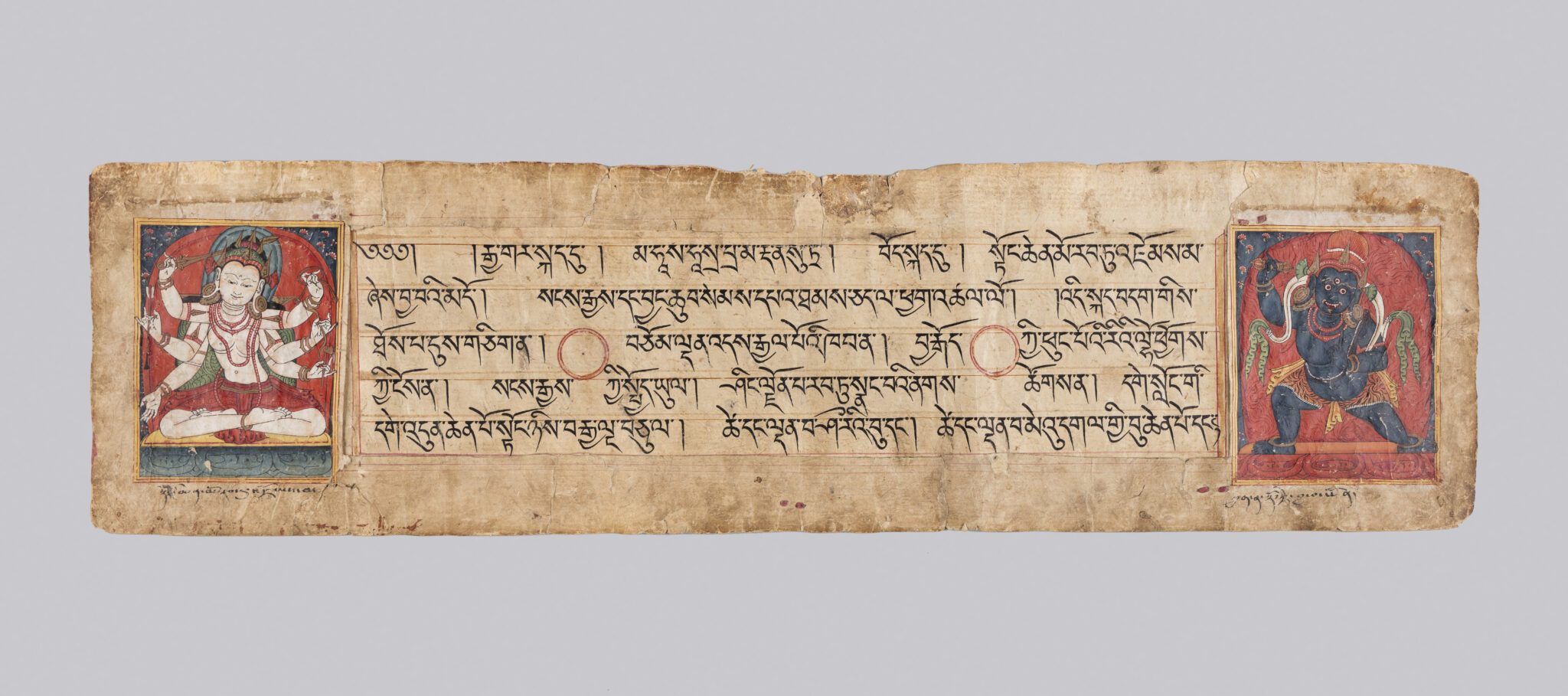

Frontispiece from The Great Destroyer of the Thousand Foes (Mahasahasrapramardani) Sutra Manuscript; Tibet;

ca. 13th–14th century; Pigments on paper; Rubin Museum of Art; C2004.33.1

Chakrasamvara Mandala; Nepal; ca. 1100; mineral and organic colorants on cotton; Image: 26 1/2 × 19 3/4 in. (67.3 × 50.2 cm); The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Rogers Fund, 1995; 1995.233; CC0 – Creative Common (CC0 1.0)

Religious Goals Permalink

Art also serves as a focal point of reference for more specific religious goals. Practitioners center their by looking at a painted or sculpted image of a during the practice focused on a particular deity or when they are initiated into the tantric practice. They see and imagine themselves entering this deity’s , which is represented by a painting or a three-dimensional model of the deity’s palace.

Art also serves as the means of instruction for monks, nuns, and laity. Narrative paintings tell inspiring of the life, lives of prominent teachers, and cultural heroes. Instructional paintings, such as the Wheel of , illustrate the fundamental philosophical Buddhist views and also remind the lay and ordained people of the impermanent nature of life.

Visualization Practice (Sadhana), leaf 10 from the Sarvavid Vairochana Visualization Album; Wangzimiao, Aokhan Banner, Inner Mongolia; ca. late 18th–19th century; pigments on paper; 10-3/8 × 10-5/8 in. (26.3 × 27 cm); Museum aan de Stroom (MAS), Antwerp, Belgium; AE.1977.0026.13-54; photograph by Bart Huysmans and Michel Wuyts, courtesy Collection City of Antwerp – MAS

Kalachakra Palace Mandala; Potala Palace, Dukhor Lhakhang, Lhasa, Tibet; 1690s; gilt-brass repoussé, with cast figures, on wooden armature, with precious stone, crystal, and glass inlays; diam. 20 ft. 4 in. (6.2 m), height approx. 63 in. (1.6 m); photograph by Walter Gross, 1997

Designed by Taranatha Kunga Nyingpo (1575–1634); Detail depicting the Buddha’s escape from life in the palace, Life of the Buddha Mural, panel 1; Phuntsok Ling Monastery, Tsang region, central Tibet (present-day TAR, China); ca. 1615–1630; photograph by Andrew Quintman and Kurtis R. Schaeffer, 2011

Wheel of Existence, detail showing image area; Tibet; early 20th century; pigments on cloth; image area 31-7/8 × 23-1/8 in. (81 × 58.7 cm), with brocade frame 65-5/8 × 40¾ × 1½ in. (166.7 × 103.5 × 3.8 cm); Rubin Museum of Art; C2004.21.1 (HAR65356)

Key Facts

- Himalayan religious art is commissioned for specific purposes.

- Religious texts outline the rules of proportions (iconometry) for depicting specific subjects such as buddhas, , deities, and idealized humans ().

- Art is used in rituals, individual practices, and popular lay, monastic, and communal festivals.

- Art is integral to structuring human beings in the Buddhist world and helping them make sense of it.

Religious arts extend beyond the visual art sphere and include ritual dance performances on special days of religious festivals. These occasions attract a whole community and people from afar who come together to view and attend the ceremonies. Itinerant storytellers called lama mani carried portable shrines to tell inspiring stories about past cultural heroes and religious masters, offering entertainment as well as instruction. This tradition is disappearing due to various reasons but mostly because of contemporary visual and communication media.

Artists, monastics, and lay people continue to patronize and create religious art in Himalayan regions and beyond for monasteries, nunneries, Buddhist centers, and ordinary people. Traditional ways of making art preserve their historical methods, though sometimes they are innovated with contemporary materials.

This theme is also explored in more detail in the exhibition module “Living Practices.”

Ritual Dance Mask of Guru Dorje Drolo; Bhutan or southern Tibet; ca. 19th century; papier-mâché, polychrome, fabric; 14½ × 13½ × 10-1/8 in. (36.8 × 34.3 × 25.7 cm); Bruce Miller Collection; photograph by John Bigelow Taylor

Bunga Dya chariot procession; Pode tol, Patan, Nepal; May 27, 1982; photograph by Bruce McCoy Owens

Manip displaying tashi gomang during a Buddhist festival; Punakha, Bhutan; 1981; photograph courtesy B&F Shaw Collection

Procession of Bunga Dya's chariot through Patan. Rohit Maharjan, "Rato Machindranath Jatra | MangalBazar to Sundhara | Patan, Lalitpur | 2079," YouTube, May 8, 2022, 15:02, https://youtube.com/p2LhXrlpGgQ.

Glossary Terms Permalink

Buddhism

Buddhism is founded on the teachings of Siddhartha Gautama, who lived sometime between the sixth and fourteenth century BCE in northern India. Buddhists believe that sentient life is a cycle of suffering and rebirth, but that if one achieves a state of awakening or nirvana, it is possible to escape this cycle. Buddhists refer to the Buddha’s teachings as the Dharma. There are many different traditions or denominations of Buddhism, including Theravada, Mahayana, and Vajrayana. Scholars also discuss regional traditions, such as Indian Buddhism, Newar Buddhism, Tibetan Buddhism, Chinese Buddhism, and so on.

Hinduism

Hinduism is a collection of religious beliefs and practices comprising a major Asian religion, practiced principally on the Indian Subcontinent and parts of Southeast Asia. Although certain practices may have their roots in the ancient Indus Valley civilization (~3300–1300 BCE), the earliest decipherable texts of Hinduism are the Vedas, ritual-mythological hymns and instructions for fire-sacrifice from around 1500–900 BCE. From around 800 to 300 BCE, new thinkers emphasized philosophical ideas like ritual union with the deity Brahman, or meditation and asceticism in the forest. One of these thinkers was Siddhartha Gautama, the founding teacher of Buddhism. Hindu temples appeared from the medieval period onward, dedicated to gods like Brahma, Vishnu, Shiva, and Mahadevi. There are also tantric forms of Hinduism, which emphasize transgressive practices and yogic ritual.

Bon is an indigenous religion of Tibet. Originally, Bon were a group of non-Buddhist ritual specialists in the court of the Tibetan emperors. From the eleventh century onward, an organized religion called Yungdrung Bon, or “Eternal Bon,” took shape. Yungdrung Bon developed in dialogue with Buddhism, incorporating deities called buddhas, scriptures modeled on the Buddhist canon, monks, and the establishment of monasteries. Followers of Yungdrung Bon trace their own origins to a founder called Tonpa Shenrab, who arrived from the semi-mythical land of Zhangzhung in western Tibet. The word “Bon” can also refer to the many non-organized indigenous religious practices, including the worship of mountain deities and making namkha. A follower of Bon is called a Bonpo.

merit

In Buddhism, merit is accumulated positive karma, or positive actions, that lead to positive results, such as better rebirths. Buddhists gain merit by reciting mantras, donating to monasteries and those in need, performing pilgrimages, commissioning artworks, reproducing and reciting Buddhist texts, and other deeds with good intentions. It is believed that merit can also be transferred to others through rituals performed to gain merit for deceased family members help them achieve a better rebirth. Merit making is an important motivation for positive ritual action, and is a prerequisite for success of religious and even secular activity.

Cham is a type of ritual dance performed in Tibetan Buddhism, often at holidays like the new year or the Monlam Chenmo prayer festival. The cham dancers, who are usually monks, put on masks and perform the actions of the deities they portray. Often these dancers are understood to “become” the deities. The dances often have an exorcistic function and generally are performed for the benefit of an entire community.

In Buddhism and Bon, a buddha is understood as a being who practices good deeds for many lifetimes, and finally, through intense meditation, achieves nirvana, or ”awakening”—a state beyond suffering, free from the cycle of birth and death. “The Buddha” of our age is Shakyamuni, or Siddhartha Gautama. He is considered the founding teacher of the religion we call Buddhism. The buddha prior to Shakyamuni was called Dipamkara, and the next buddha will be Maitreya. These are known as Buddhas of the Three Times. Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhists believe that there are infinite buddhas in infinite universes, who have many bodies or emanations. Other important buddhas include Amitabha, Vairochana, Bhaishajyaguru, Maitreya, and many more.

patronage

A practice of hiring and commissioning artists to create works of art. In religious context patrons were often rulers, religious leaders, as well as ordinary people. (see also donor)

In Vajrayana Buddhism or Bon, a mandala refers to a cosmic abode of a deity, usually depicted as a diagram of a circle with an inscribed square that represents the deity enthroned in their palace, surrounded by members of their retinue. Mandalas can be painted, three-dimensional models, architectural structures, such as temples or stupas, or composed as arrangements of images within a temple. The instructions for creating and visualizing mandalas are usually found in ritual texts, such as tantras and sadhanas. Mandalas can be used in initiation ceremonies, visualized by a practitioner as part of deity yoga, consecrated and used to represent the divine presence within ritual space, offered to the deities as representations of the entire universe. A similar concept in Hinduism is a yantra.

visualization

Visualization is a process of using one’s imagination to transform reality. A practitioner imagines in their mind’s eye the deity with the associated enlightened qualities they wish to embody themselves. When focused on a specific deity, visualization and related ritual practices are called deity yoga. Visualization is a fundamental element of such practices described in texts known tantras, which define a system of meditation and ritual meant to transform the mind and body.

iconography

In the Himalayan context, iconography refers to the forms found in religious images, especially the attributes of deities: body color, number of arms and legs, hand gestures, poses, implements, and retinue. Often these attributes are specified in ritual texts (sadhanas), which artists are expected to follow faithfully.

iconometry

Iconometry means the measurement of icons or religious images. Especially in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition, detailed manuals exist that use precise proportional measurements to standardize the iconography of major deities, and maintain their correct proportions, regardless of scale. These proportions are commonly expressed visually in artist manuals as iconometric grids.