Riga Shakya

Postdoctoral Research Scholar at the Heyman Center for the Humanities and Lecturer in East Asian Languages and Cultures

Columbia University

Empire's Long Shadow Permalink

The violent and transformative processes of empire-building and colonialism have irreparably shaped the cultures, languages, politics, landscape and environment, intellectual traditions, and knowledge–making practices of the Himalayan, Tibetan, and Inner Asian regions and their inhabitants.

While there is no singular model of imperial or colonial domination, empires across world history can be broadly understood as expansionist polities that sought to exercise varying degrees of cultural, economic, political, and social control over territories acquired through conquest from a metropolitan center. The term imperialism, therefore, sheds light on the diverse methods by which an empire exercised this domination over its territories, whether through settlement, sovereignty, or indirect mechanisms of control. Often overlapping with imperialism, the practice of colonialism saw empires settling their populations on newly conquered territory for economic exploitation, the extension of political authority, and the reinforcement of territorial claims, among other goals.

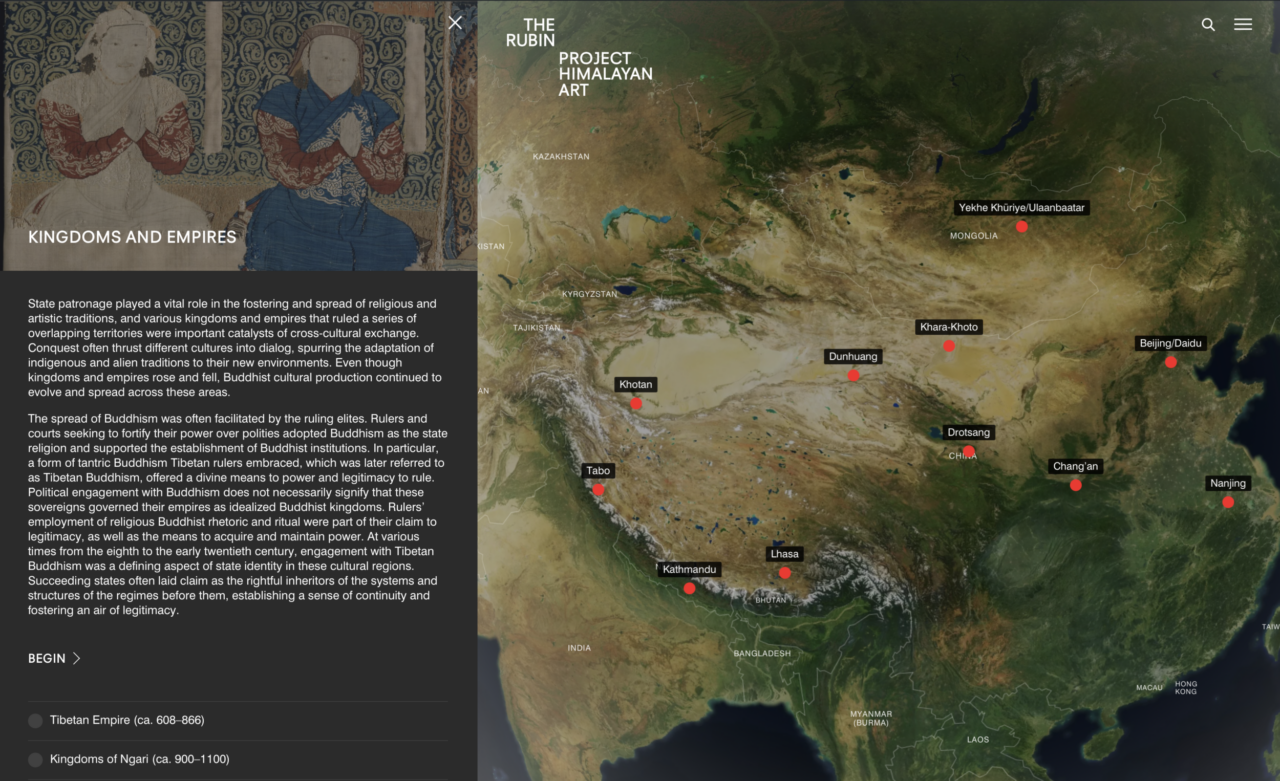

The long history of imperial expansion by regional conquest empires—such as the , the , and successive China-based dynastic empires (the and )—contributed to the forging of structures of political authority and territory, cross-cultural ties, cosmopolitan religious and trade networks, and increased mobility and interconnection across Tibetan, Himalayan, and Inner Asian . (For more information on overlapping expanses of successive regional kingdoms and empires in the greater Himalayan region, view the map narrative Kingdoms and Empires.) Galvanized by political, economic, technological, and intellectual developments, the advent of modern European colonialism in Asia in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries saw the introduction of pernicious and sophisticated forms of material, structural, and cognitive domination over these regions, the effects of which last to the present day.

The Castle and Temple of Yumbu Lagang, Yarlung Valley, U region, central Tibet (present-day TAR, China); founded ca. 6th century; photograph by Vladimir Zhoga

Ruins of the capital city of the Tangut Kingdom Khara-Khota (present-day Inner Mongolia, China)

Wall at Qara-Qorum, capital of the Mongol Empire (1235–1260); Övörkhangai Province, Mongolia; photograph by Karl Debreczeny, 2013

Longguodian (Hall of Dynastic Prosperity); Qutansi; Drotsang, Tsongkha, Amdo region, eastern Tibet (present-day Ledu County, Qinghai Province, China); 1427; photograph by Karl Debreczeny, 2001

Putuo Zongcheng Temple at Chengde, China; October 1, 2007; photograph by Gisling; published under a Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0 license

Empire Across the Himalayas Permalink

These objects represent different stages of imperial influence across the Himalayas. At different times, the Tibetan Empire, various kingdoms of Ngari, Tangut Kingdom, Mongol Empire, Ming dynasty, and Manchu Qing dynasty all played significant roles in shaping the art and cultures of the region.

Empire, Colonialism, and Knowledge Permalink

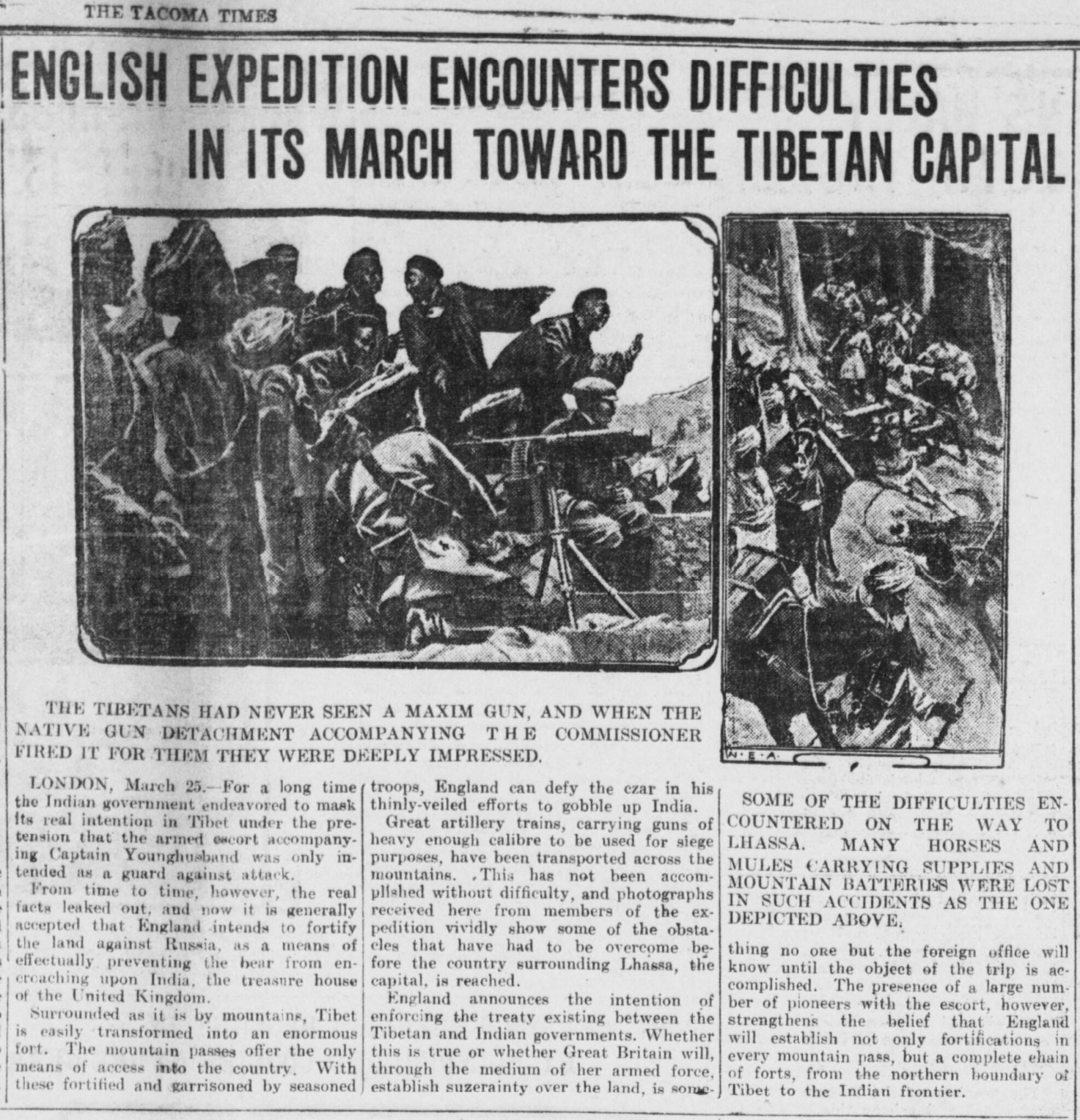

Tibet was never formally colonized by a European power, but experienced both direct and indirect imperial encounters with the Qing dynasty, and the and Russian Empires. The Great Game, the rivalry between British and Russian Empires over influence in Central Asia, primarily in Afghanistan, Persia, and Tibet during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries contributed to tense inter-imperial diplomatic, military, and intelligence conflicts and encounters in Tibetan, Himalayan, and Inner Asian regions. British colonial rule over the Indian subcontinent precipitated the importance of these regions as sites of strategic geopolitical contestation and also as terra incognita in the West, attracting the attention of scholars, soldiers, spies, and explorers alike.

The mobilization of knowledge was essential to imperial projects worldwide. Amidst these imperial contestations, colonial knowledge-making practices about Tibet and the Himalayas, such as anthropology, disciplinary history, image making and photography, and cartography, both produced and were underpinned by the “rule of colonial difference,” a term posed by the postcolonial theorist Partha Chatterjee to bring attention to the insidious hierarchies drawn between “civilized” colonizers and “uncivilized” colonized populations. The production of “useful” information—about local customs and tradition, indigenous structures of power, social practices that could be “improved,” and resources that could be exploited—facilitated governance, whether by engaging local elites in the colonial project, displacing traditional structures of political authority, extending systems of surveillance and control, or otherwise expanding the reach of imperial rule.

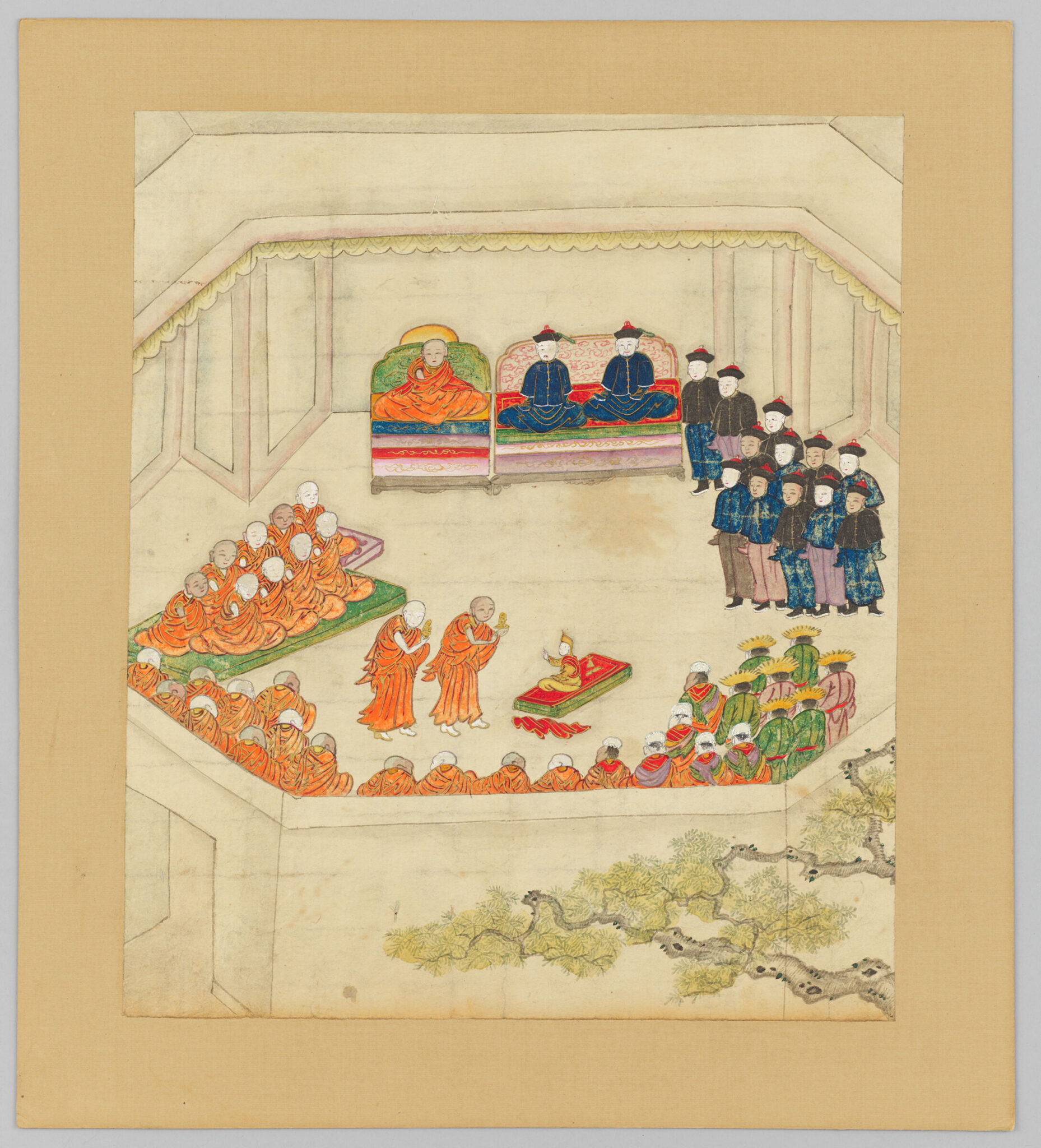

Page from an album: Finding of a Dalai Lama; East Asia, China; 19th century, Qing dynasty, 1644-1911; album leaf, painting; painting: (13 3/8 × 11 3/8 in.) 33.9 × 28.9 cm with mounting: (16 3/8 × 14 11/16 in.) 41.6 × 37.3 cm; Harvard Art Museums/Arthur M. Sackler Museum, Bequest of the Hofer Collection of the Arts of Asia, 1985.863.5

Sir Charles Bell (British, 1870–1945); Rabden Lepcha in Delhi; ca. 1915; glass negative; 5 3/8 x 3 1/2 in. (13.8 × 8.8 cm); Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford, 1998.285.603; photograph © Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford

“English Expedition Experiences Difficulties in its March Toward the Tibetan Capital,” The Tacoma Times (Tacoma, WA), March 25, 1904, p. 4. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Library of Congress.

While each of these imperial relationships have their unique histories, the anthropologist and historian Carole McGranahan argues that each imperial polity sought “to put their imprint on Tibetans through an educating of sensibilities, a cultivating of political affiliation, a delineating of favorable borders, and/or a disciplining of the population.” The imperial legacies of Tibet’s past continue to reverberate even after the decolonization of Asia in the mid-twentieth century, with China employing the logic of empire in advancing its contemporary colonial project in Tibetan regions, and the durable influence of colonial knowledge over colonized populations and their representations and self-representations both inside and outside the region in the contemporary.

Collecting as Colonial Practice Permalink

The history of museum institutions and the practice of object collection are intimately linked to the history of empires and the era of European colonialism. The wealth generated from imperial expansion and the exploitation of resources and people enabled the growth of private and institutional museum collections around the world. Sophisticated colonial knowledge-making practices, such as anthropological research and image making, as well as more overt practices such as looting, theft, and other forms of unfair object acquisitions contributed and continue to contribute directly to the circulation of Himalayan, Tibetan, and Inner Asian visual and material culture across the world.

Objects and Expeditions/Actions Permalink

Below are examples of objects paired with the colonial actions/expeditions during which they were acquired.

The Boxer Rebellion (1860) Permalink

Sword, Scabbard, and Sword Belt; Tibetan; blade ca. 16th–17th century; hilt, scabbard, and belt ca. early 18th–mid-19th century; steel, silver, copper, gold, coral, wood, leather; sword length without scabbard 39 in. (99.1 cm), weight 2 lb. 9.4 oz. (1173.7 g); scabbard weight, 1 lb. 15.7 oz. (898.7 g); The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Purchase, Arthur Ochs Sulzberger Gift, 2014; 2014.262.1a–c, 2014.262.2a, b; CC0 – Creative Commons (CC0 1.0)

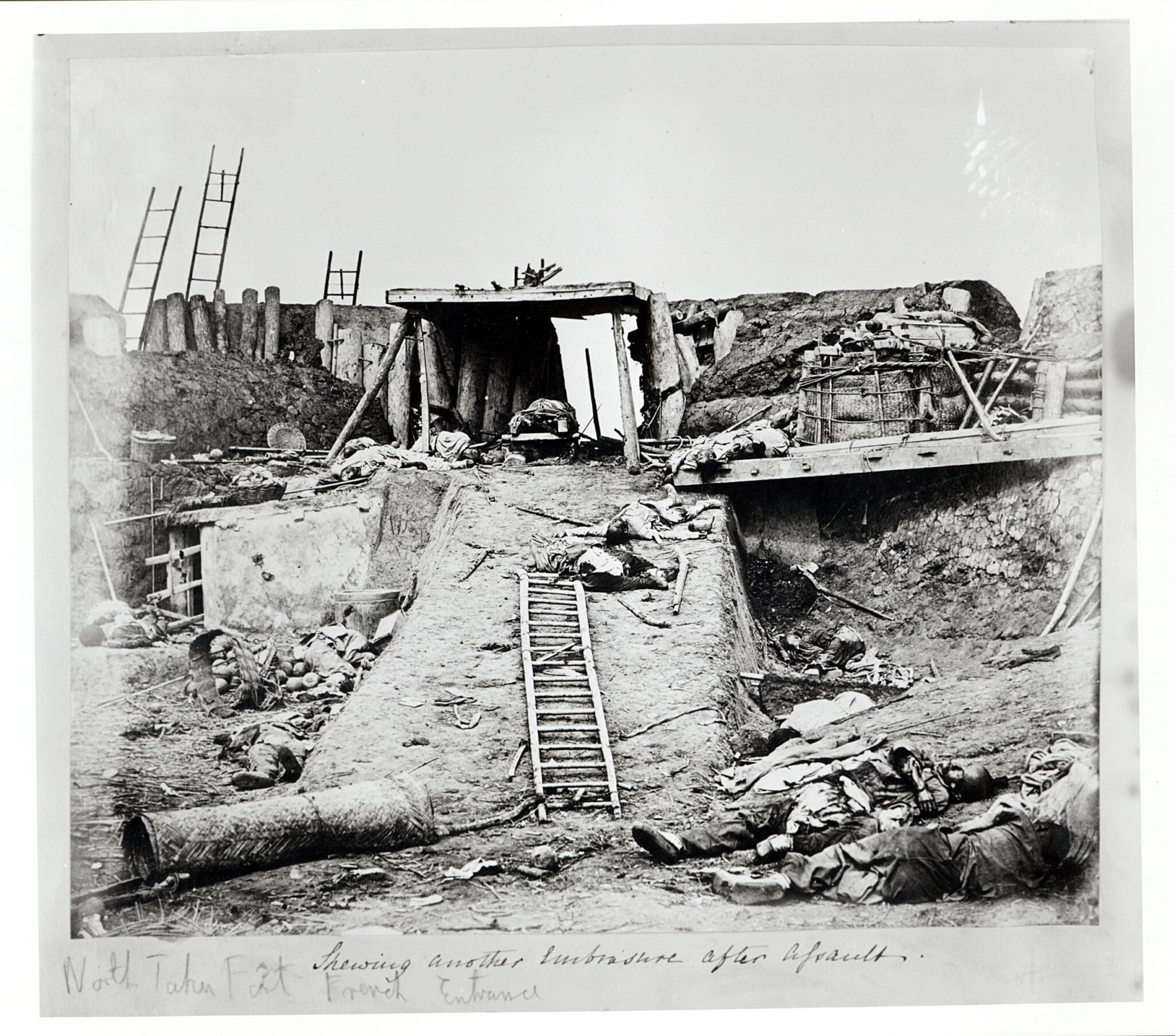

Felice Beato (British, 1832–1909); The North Fort at Taku, China, 1860; 1860; albumen print; National Army Museum, London; NAM 1962-08-16-10; photograph © National Army Museum/Bridgeman Images

Felice Beato (British, 1832–1909); Taku, China: the North Fort bearing raised British and French flags; Chinese corpses in the foreground; on the day of the fort’s capture by the English and French armies during the Second China War; 1860; albumen print; Wellcome Collection 569703i

British Younghusband invasion/expedition into Tibet (1903–4) Permalink

Case (amulet) with plaque (Tsa Tsa) and fragment; Tibet, China; 19th century; bronze, paper; 4 1/8 × 3 3/4 × 13/8 in. (10.50 × 9.50 × 3.50 cm); The British Museum, 1008515001; photograph © The Trustees of the British Museum

F. M. Bailey (English, 1882–1967); Photograph taken by F. M. Bailey in Tibet; 1903–4; nitrate negative; 3 1/2 × 5 7/8 in. (9 × 14.9 cm); International Dunhuang Programme Neg 1083/14(377)

Seals Affixed to Treaty of Lhasa (ca. 1904); Image after Younghusband, Sir Francis Edward. India and Tibet: A History of the Relations Which Have Subsisted Between the Two Countries from the Time of Warren Hastings to 1910; With a Particular Account of the Mission to Lhasa of 1904. London: John Murray, 1910

Pyotr Kuzmich Kozlov's expedition/excavation at Khara-khoto (1907–9) Permalink

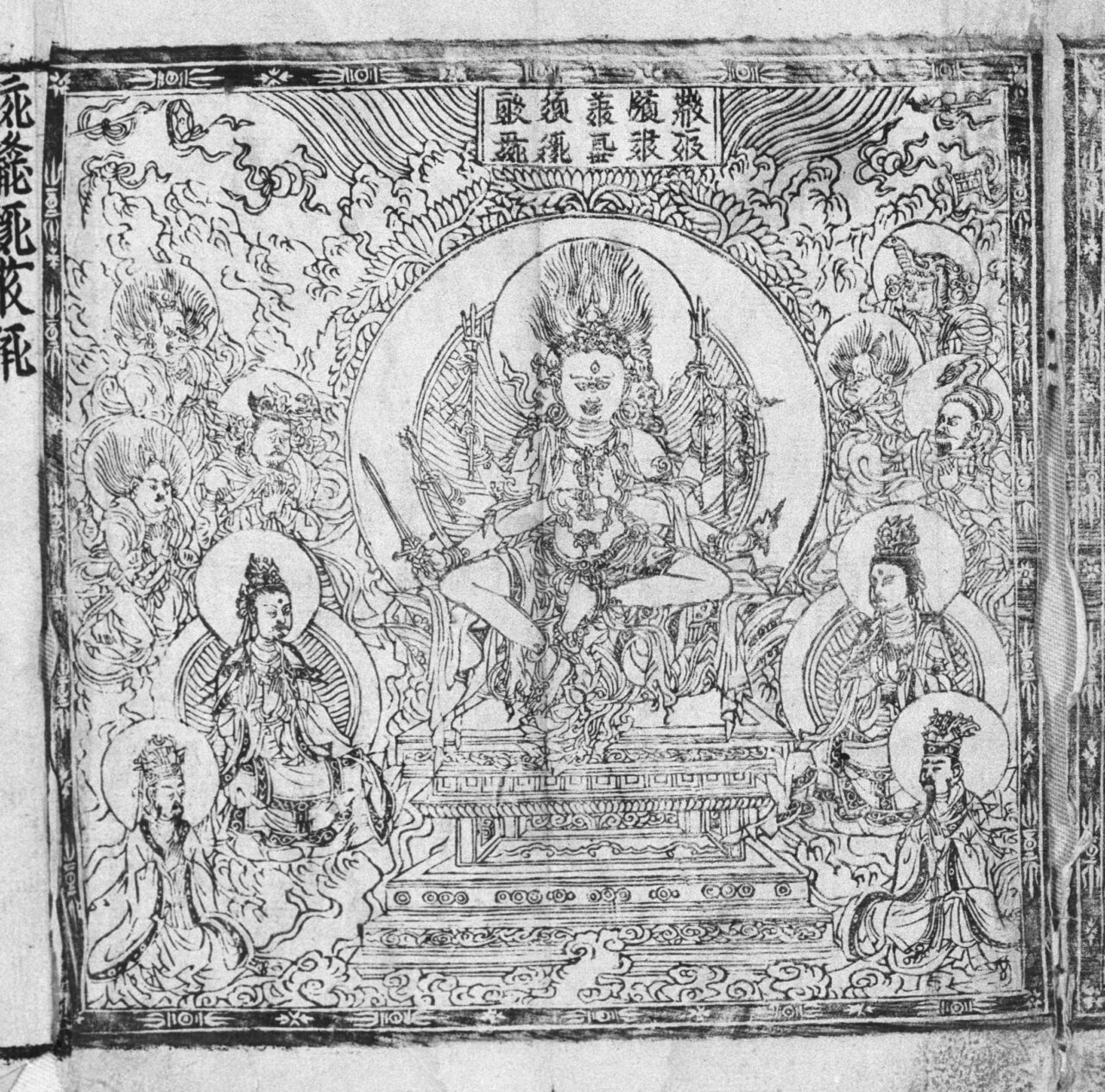

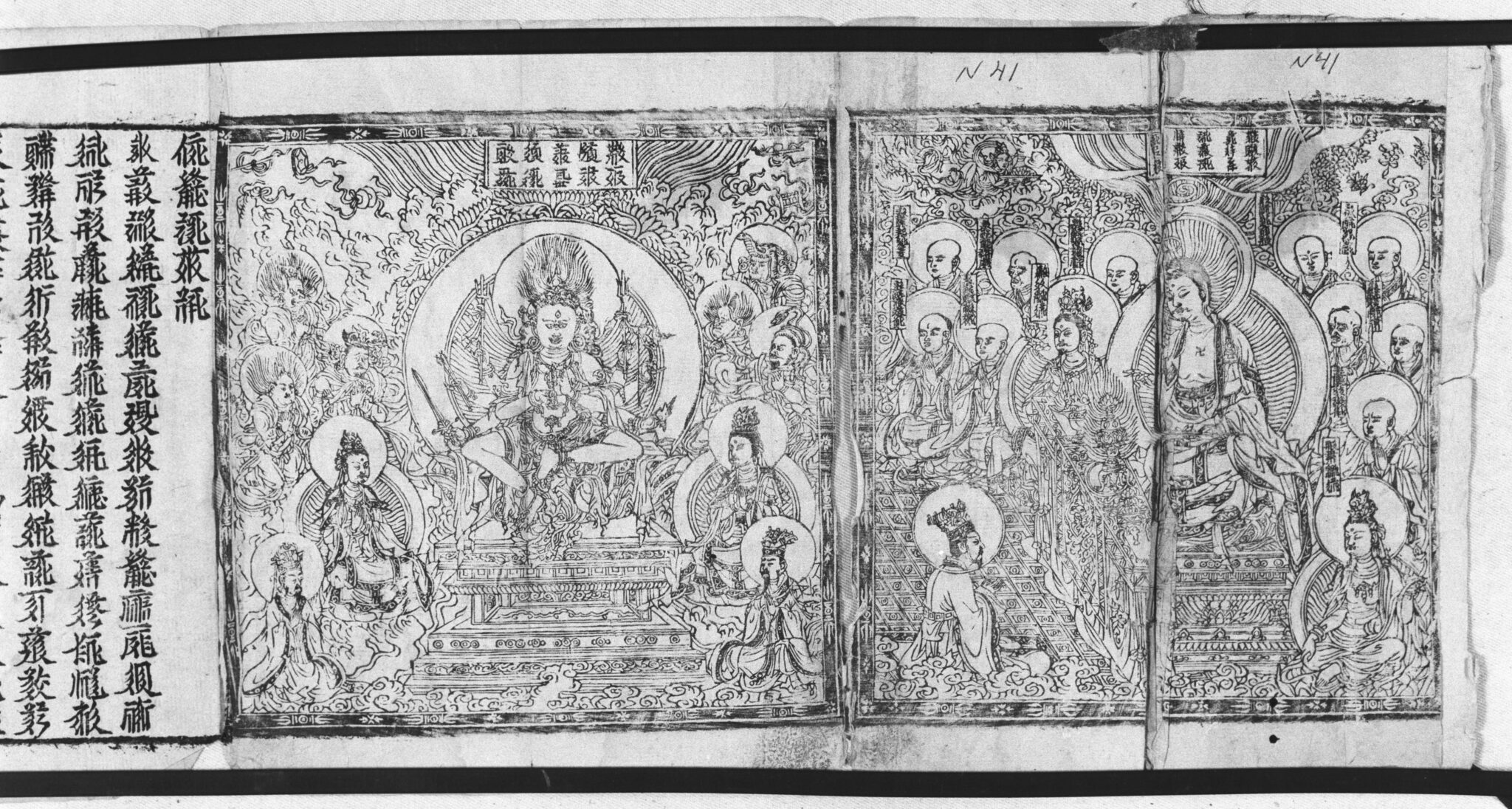

A Pancharaksha Text with Frontispiece Illustrations; excavated from Khara-Khota, Tangut Kingdom (Xixia), Gansu Province, China; ca. late 12th century, reign period of the emperor Renzong (1124–1193, r. 1139–93); xylographed ink on paper, concertina binding, 60 pages of text and 4 illustrated pages; 10 7/8 × 4 3/8 in. (27.5 × 11 cm); Institute of Oriental Manuscript Research; P. K. Kozlov Collection; Russian Academy of Sciences, Saint Petersburg, Russia; Tang 214, n40–41/1; image after Ecang Heishui cheng wenxian vol. 29 (Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, 2019), 100

Karl Bulla (Russian, 1853–1929); Traveler Colonel Peter Kuzmich Kozlov, 1910; Central State Archive of Film, Photo and Record Documents of Saint Petersburg

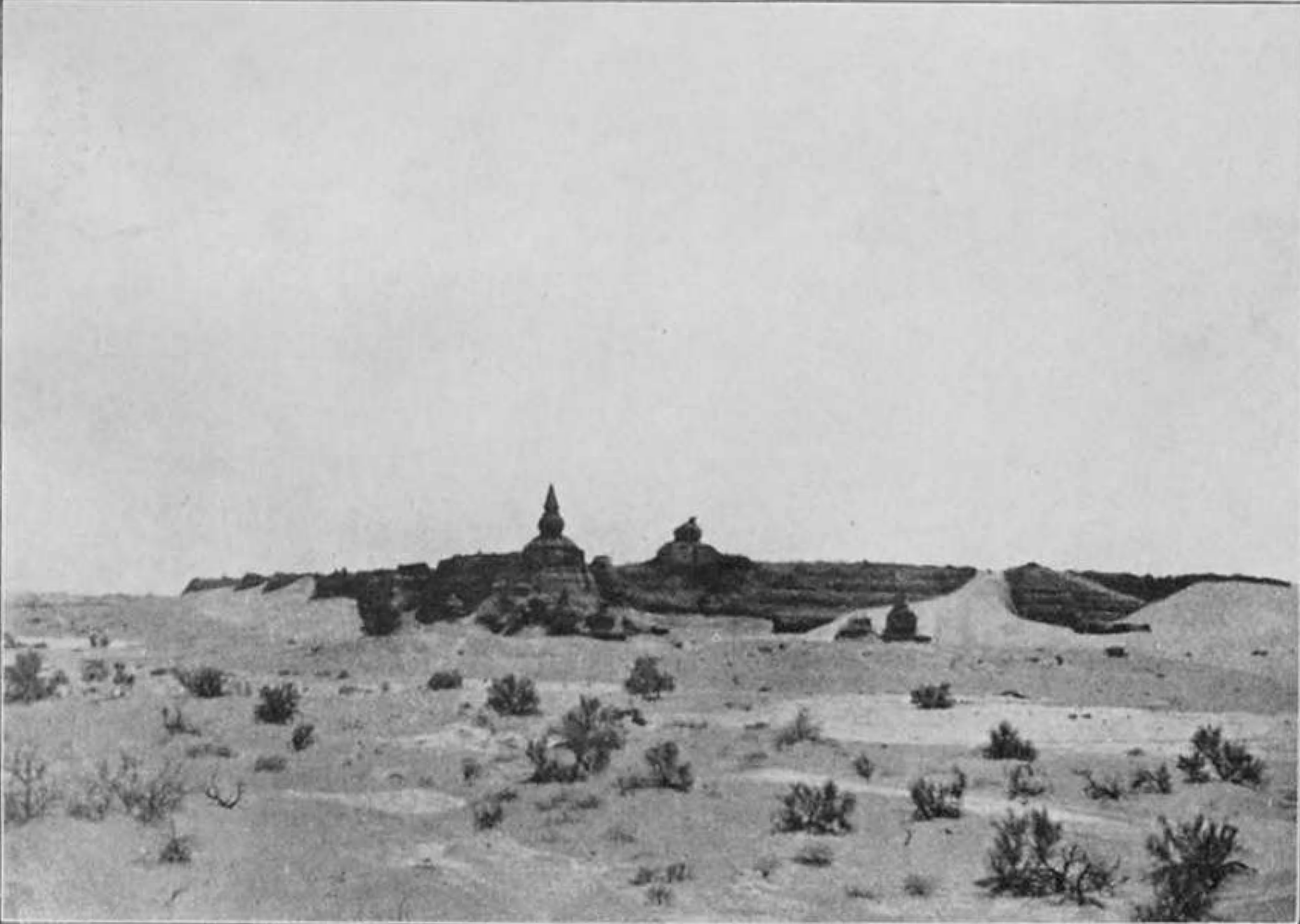

Khara-Khoto from north-west, 1908; from “News From Mongol-Sichuan Expedition” by Pyotr Kozlov, Saint Petersburg, 1908

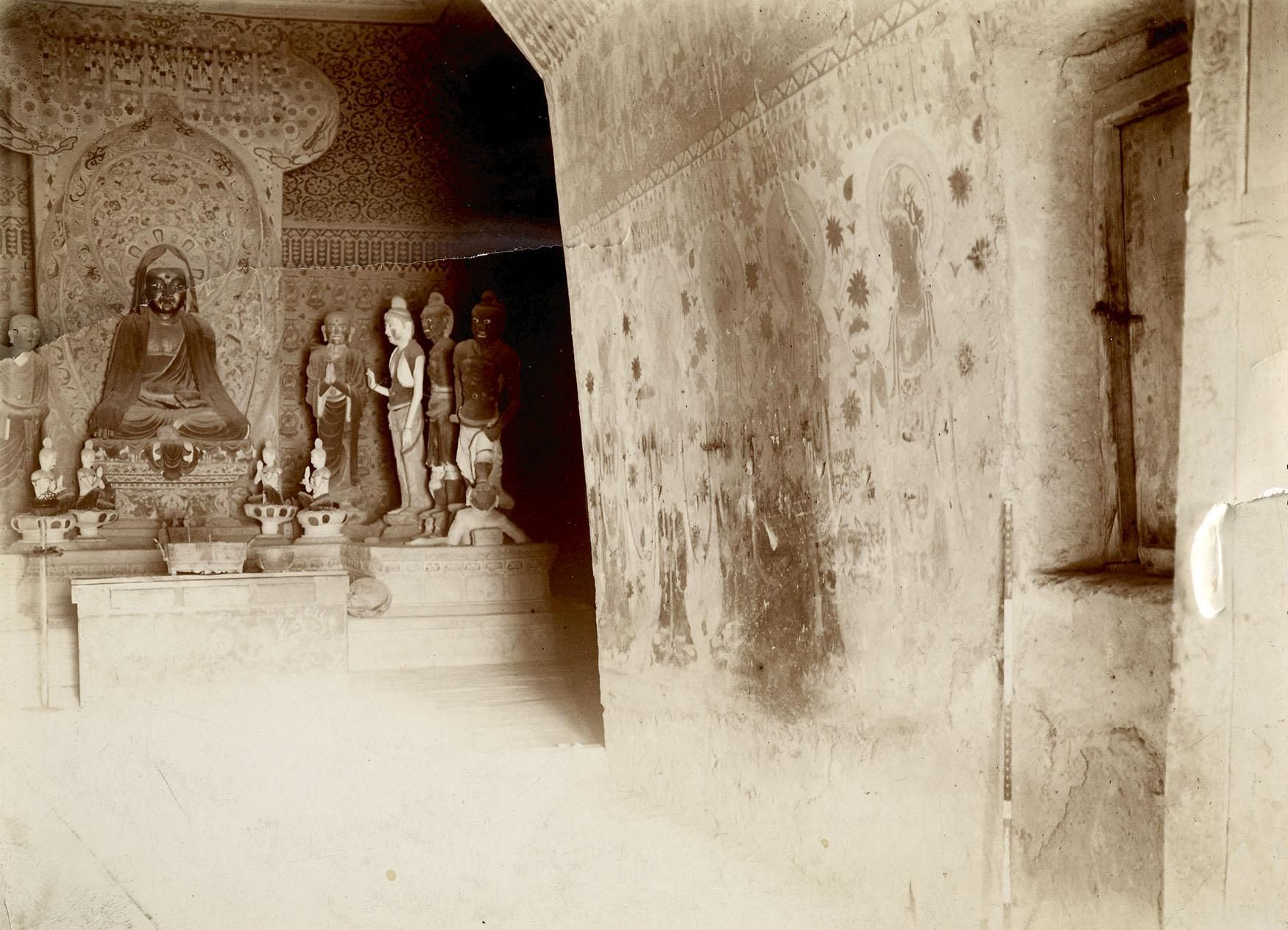

Aurel Stein’s field mission to Dunhuang (1907) Permalink

Paradise of Bhaishajyaguru; Dunhuang, China; 836; ink and color on silk; 60 × 70 in. (152.3 × 177.8 cm); The British Museum, London; 1919,0101,0.32; photograph © The Trustees of the British Museum. All rights reserved

Group with Aurel Stein and assistants at Ulugh-Mazar (north of Chira, in Xinjiang, present-day China). Left to right, seated: Jiang Xiaowang, Stein with his dog Dash, Rai Bahadur Lal Singh. Standing: Ibrahim Beg, Jaswant Singh, Naik Ram Singh. Photograph © Library of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Stein LHAS Photo 37/5 (79)

Aurel Stein (Hungarian, 1862–1943); Stein’s image of an empty cave 16, 1907; 4 11/16 × 6 5/16 in.; International Dunhuang Programme, Photo 392/59(1)

Sven Hedin's expeditions to Central Asia (1893–1935) Permalink

Vajrapani; Efi (efü?) khalkha süme, Shiliin Gol League (formerly in Chakhar), Inner Mongolia; mid-18th century; gilt-copper alloy with lacquer and pigments, inset with gems; height: 73 in. (185.4 cm); Stockholm Ethnographical Museum (Folkens Museum Etnografiska); 1935.50.1714; photograph by John B. Taylor

Sven Hedin making surveys with his leveling instrument in Kara-Koschun in the Taklamakan desert, 1899; The Museum of Ethnography, Sweden, 1025.0072, 1021.II.0072

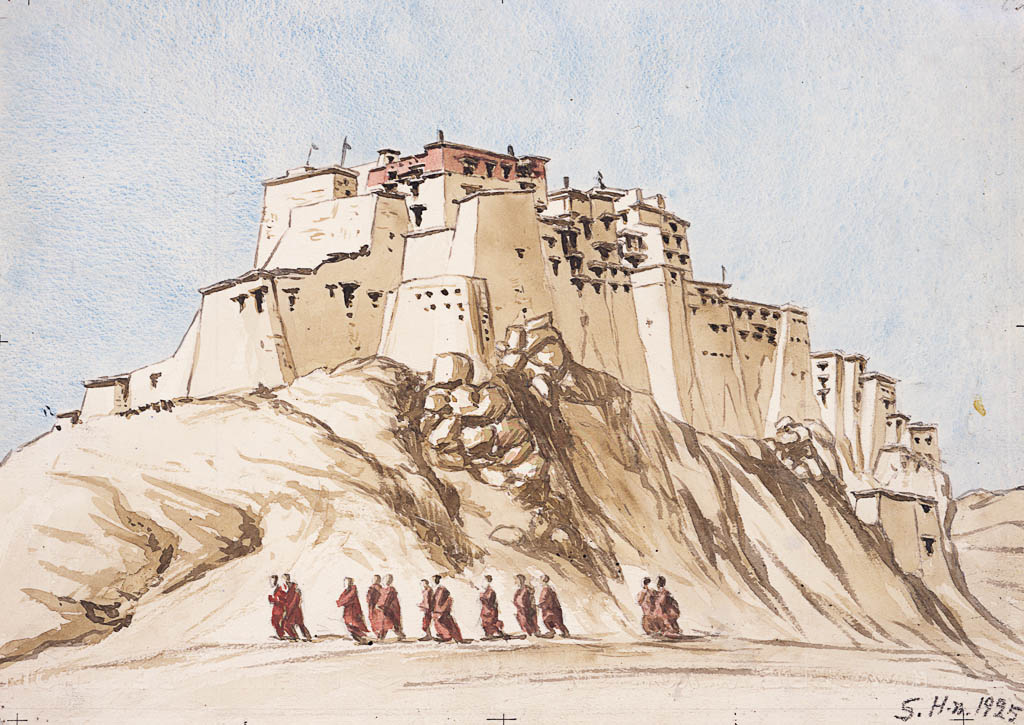

Sven Hedin (Swedish, 1865–1952); Shigatse Dsong, 1917; illustration from Southern Tibet by Sven Hedin

Extracting these objects from their original contexts and presenting them in the visual order of museums led to the erasure of indigenous aesthetic sensibilities and knowledge practices, which were supplanted by aesthetic lenses produced by colonial hierarchies of knowledge, upholding the dominant narratives of empires and nation-building projects. However, even under such conditions of domination, Tibetan, Himalayan, and Inner Asian communities have articulated powerful aesthetic visions of negotiation, resistance, and subversion (see examples in images below) that contest the asymmetrical power relations engendered by empire and colonialism.

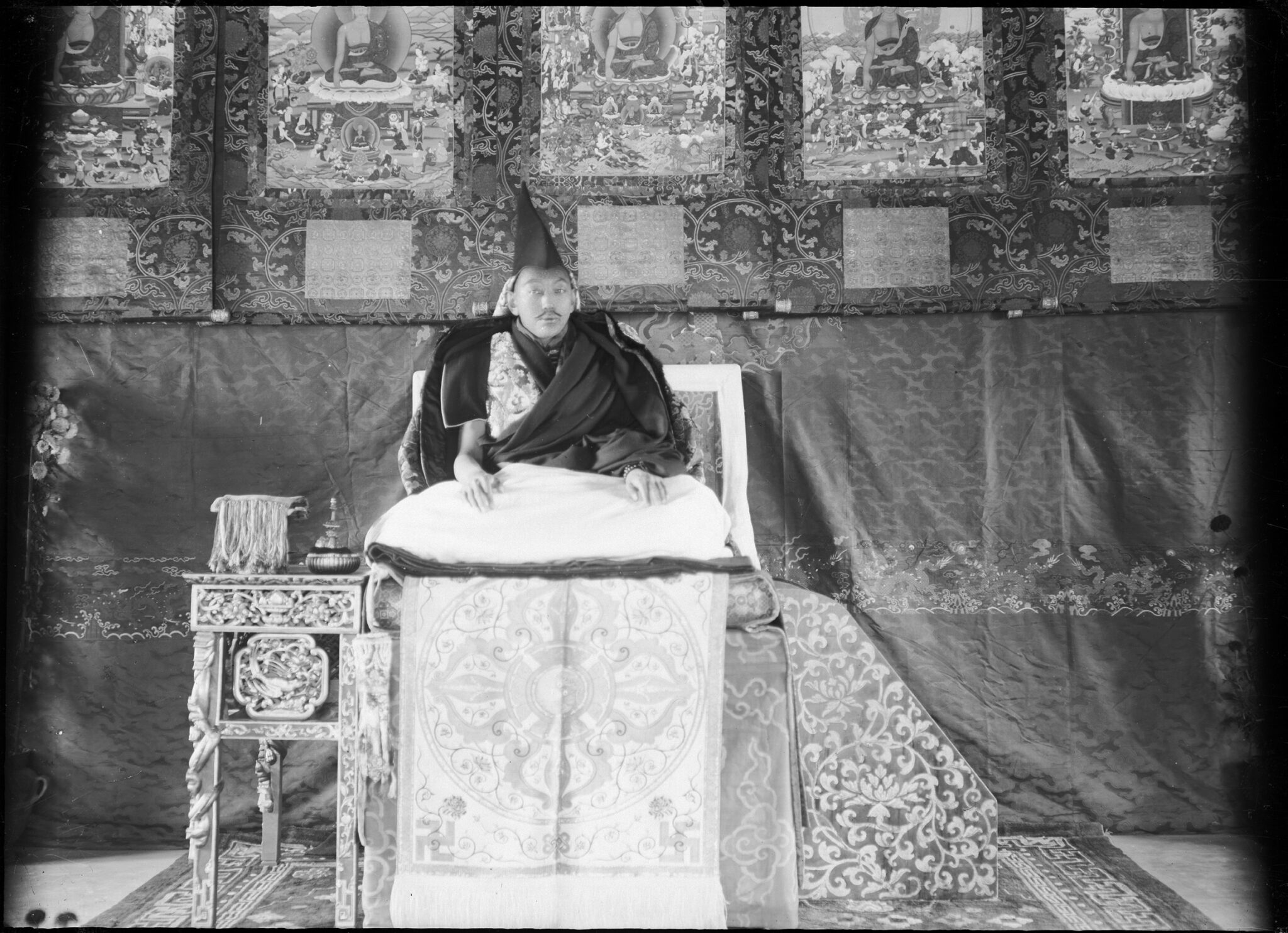

Sir Charles Bell (British, 1870–1945) and Rabden Lepcha (Sikkimese, act. early 20th century); The Thirteenth Dalai Lama on Throne in Norbulingka; Norbulingka, Lhasa; October 14, 1921; lantern slide from negative; 3 3/16 × 3 3/16 in. (8.1 × 8.1 cm); Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford; 1998.285.88.2; photograph © Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford

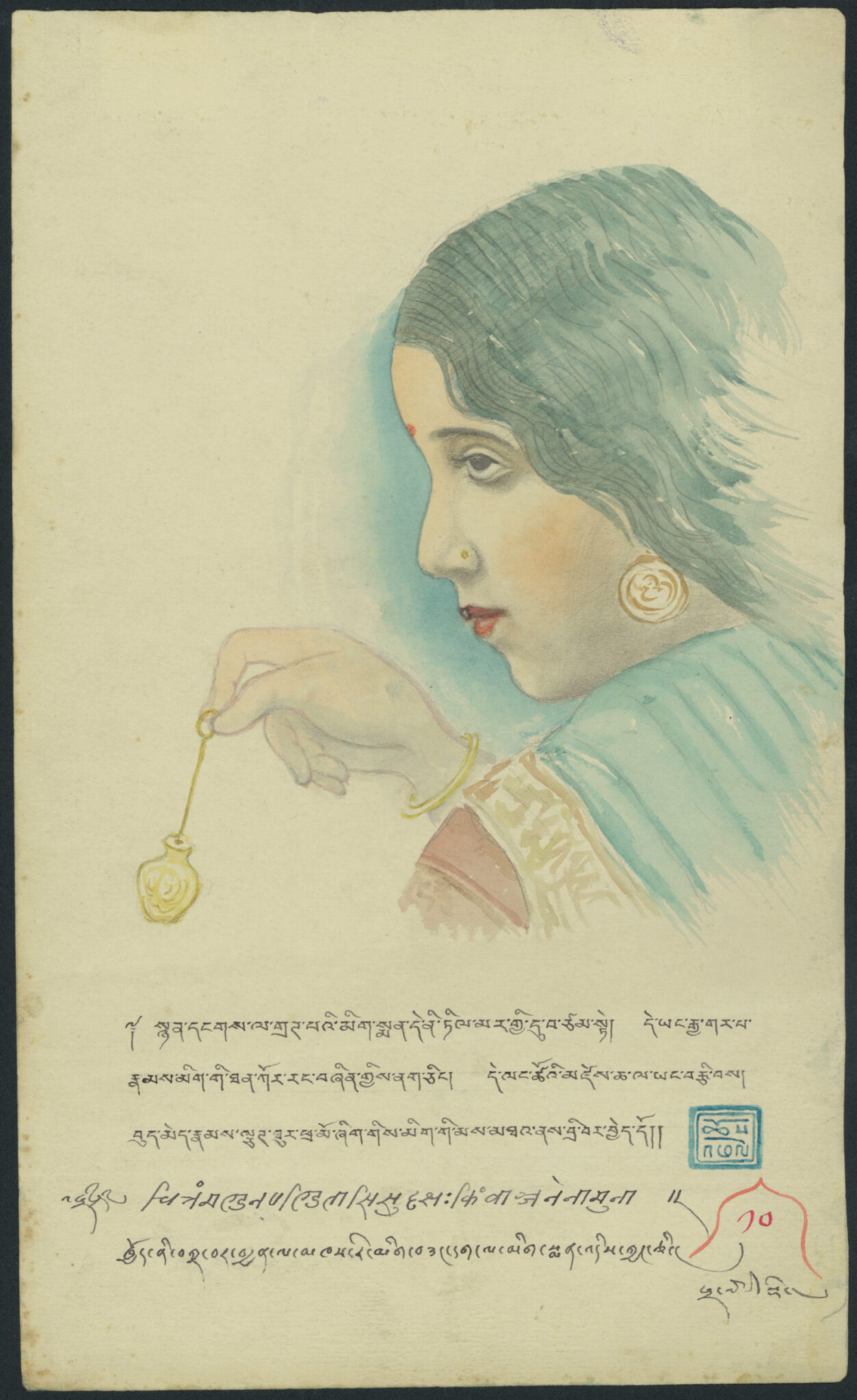

Gendun Chopel (Tibetan, 1903–1951); Woman Applying Kohl; India, ca. 1940; watercolor; 10 × 6 in. (25.5 × 15.4 cm); Private Collection; image after Xiong Wenbin and Zhang Chunyan, eds. 2012. 2012 nian de zhui xun: Xizang wen hua bo wu guan Gendunqunpei sheng ping xue shu zhan 2012 年的追寻: 西藏文化博物馆根敦群培生平学术展. Beijing: Zhongguo Zang xue chu ban she; photograph courtesy Latse Library

Gade (b. 1971, Lhasa); Ice Buddha No. 1 (8 photographs); Lhasa; 2006; chromogenic prints; each 31 1/2 × 19- 5/8 in. (80 × 50 cm); photographs by Jason Sangster, courtesy Gade

Project Himalayan Art Resources Permalink

For more on empires, visit Project Himalayan Art’s Kingdoms and Empires map narrative.