Stories, morality tales, and legends are an important part of Buddhist culture. These “teaching” stories originated in India and were embraced in all Buddhist cultures, where they were adapted to local traditions. Particularly, the life story, his teachings, and events from his many previous lives serve as a template for later biographies of famous practitioners and teachers. The result is a rich tapestry of storytelling of purely Tibetan, Nepalese, and other cultural narratives.

The Buddha's Stories Permalink

Stories about the young prince who renounced his life of luxury to seek liberation from suffering is the story familiar to Buddhists around the world. Then known as Siddharta, he spent years searching for enlightenment, and after attaining it he spent the rest of his life teaching it to others as the Buddha.

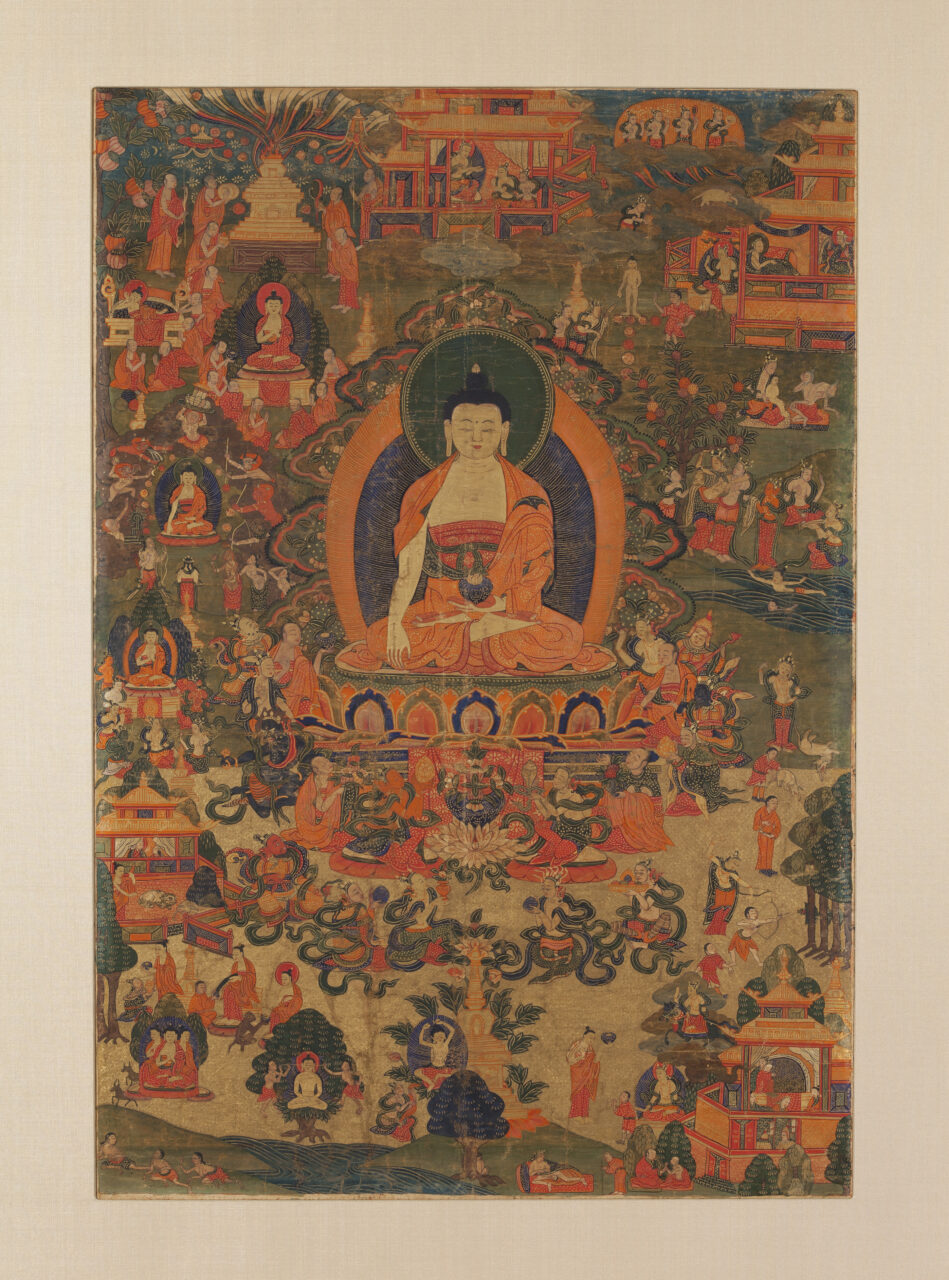

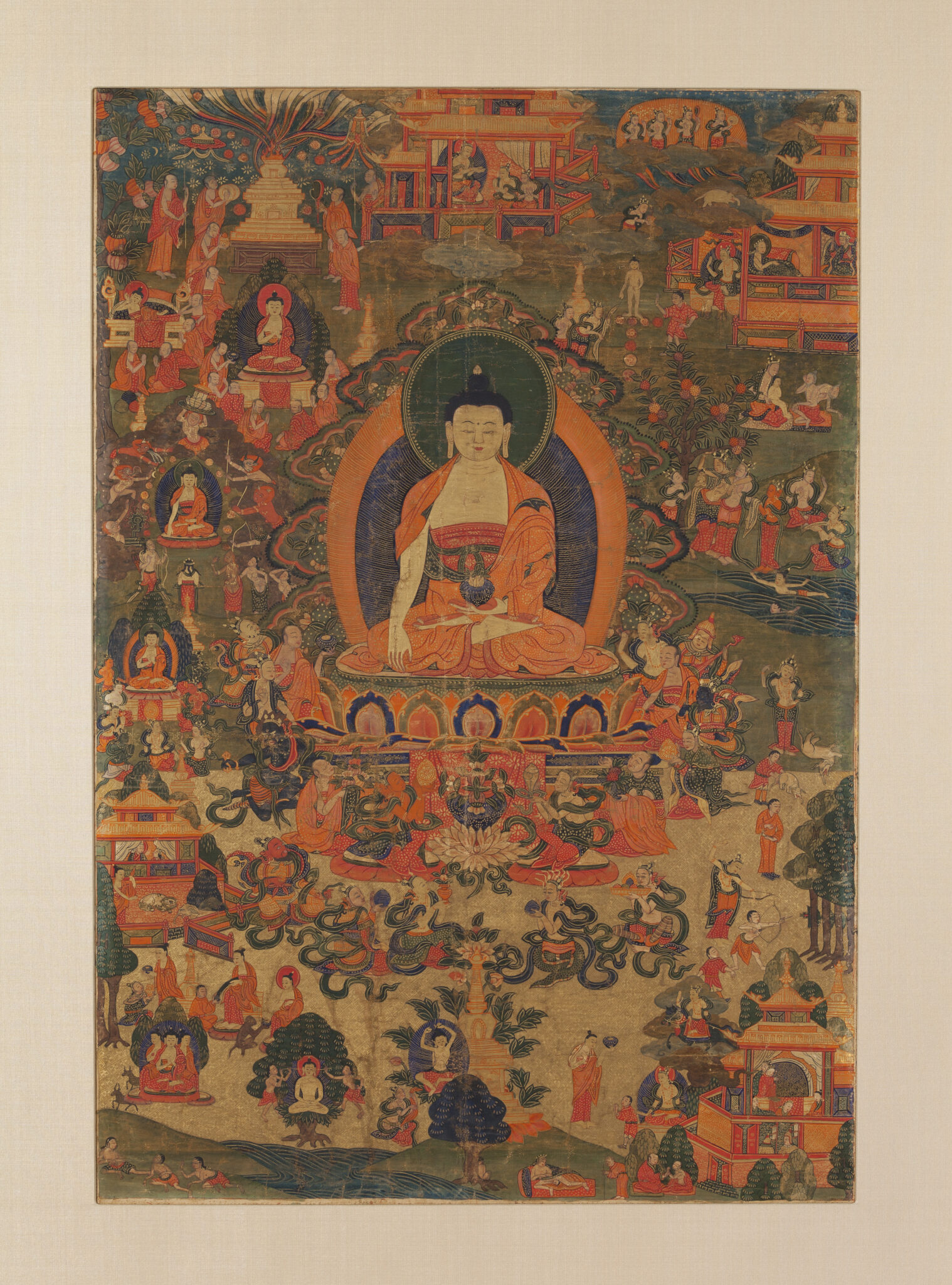

The Buddha’s teachings and the biographical accounts of his journey toward awakening were originally recounted orally. While the exact dates of the Buddha’s life are still debated, he is believed to have lived sometime between the sixth and fourth century BCE. His full life story was not written down until the second century CE, but visual narratives of various episodes from his life and previous lives have been the main subject of Buddhist art from its very beginning. They continue to be represented in various sculptural and painted forms in all Buddhist cultures today.

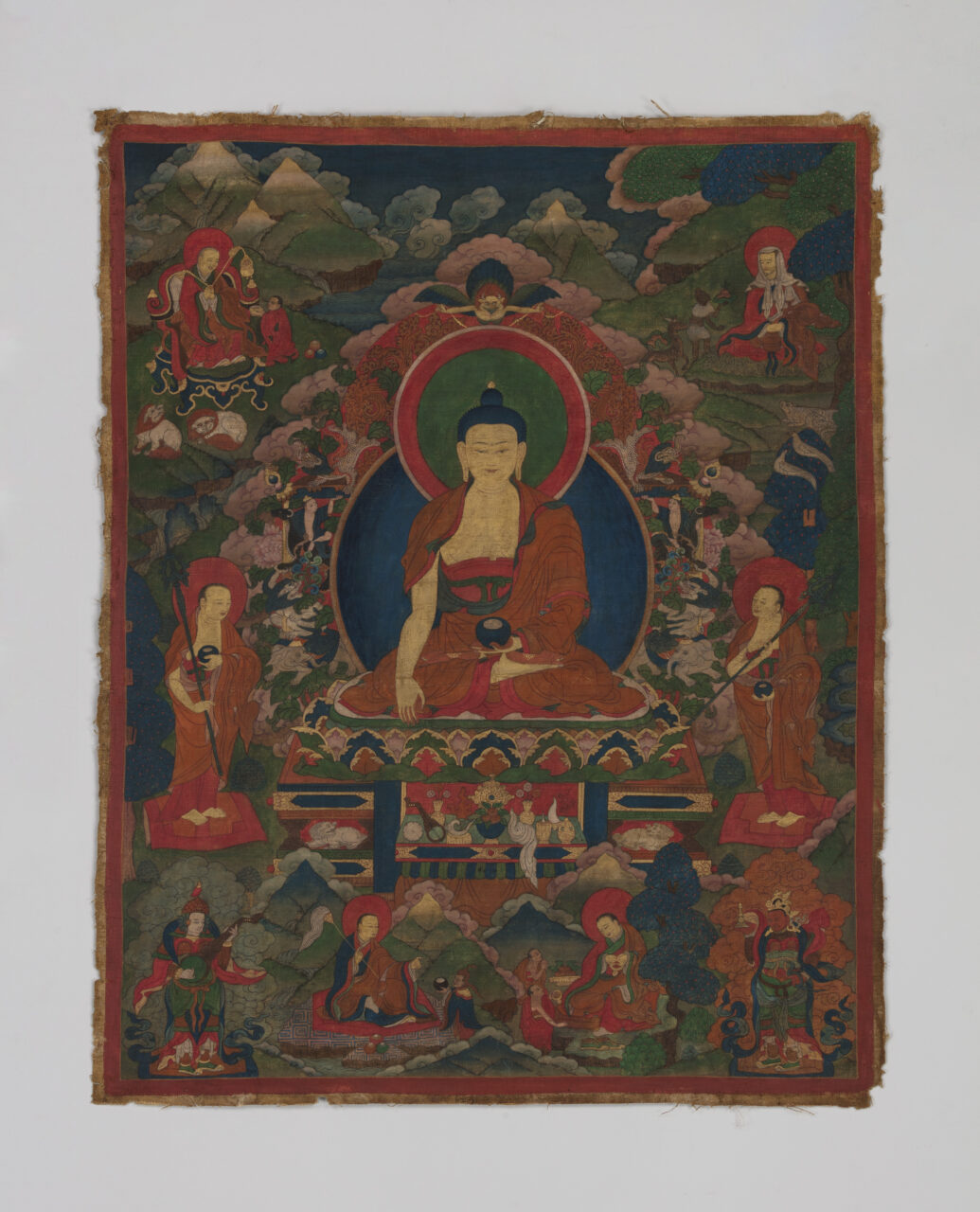

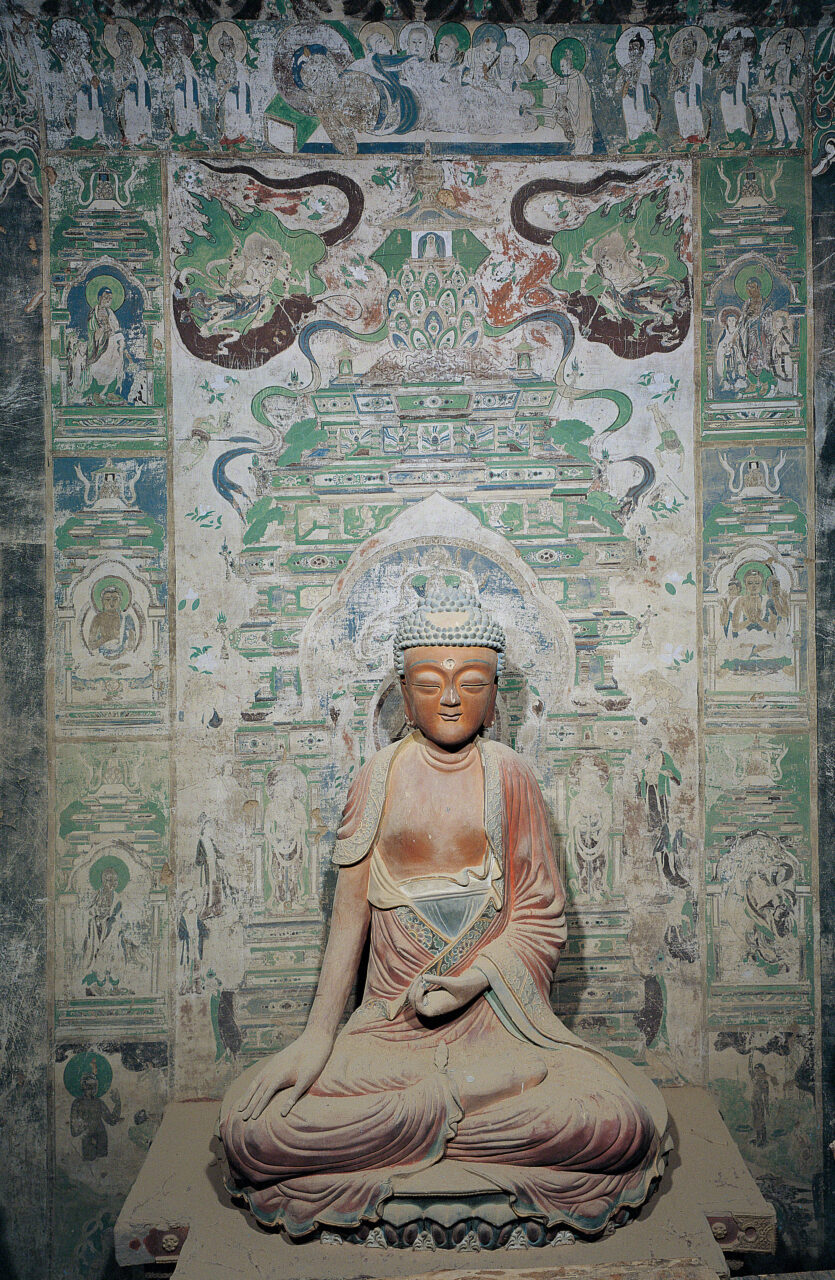

Tibetan depictions of the Buddha’s life are found in a variety of art mediums, from murals to scroll paintings. A visual representation of the of the Buddha’s life developed in India during the fifth through the ninth centuries became prominent in the medieval art of many Buddhist countries—from the Indian kingdoms of and Sena to city states, and from Central Asian empires to Tibetan and Burmese kingdoms. The scenes are depicted within architectural structures but do not represent the events as occurring within the sites. It visually refers to commemorative shrines built at the sites where the events occurred.

Tibetan Depictions of the Buddha's Life Permalink

Exhibition Objects

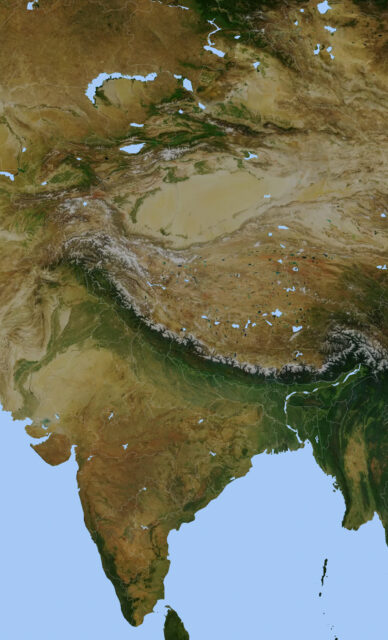

Current locations of the places mentioned in the Buddha Shakyamuni’s life.

Art Interactives of Images of the Life of the Buddha Permalink

Life Stories of Masters Permalink

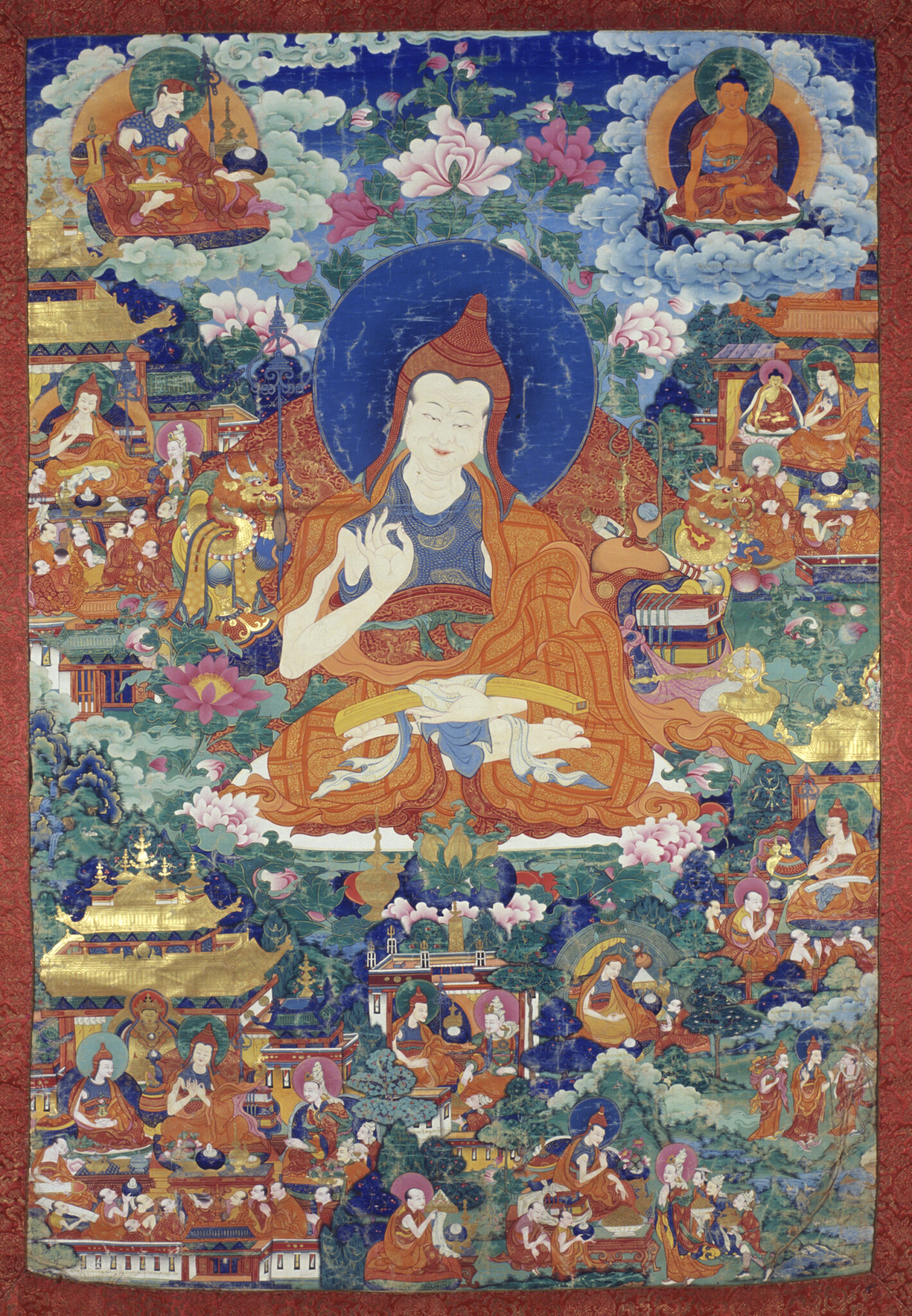

A painting can be a historical record. Some paintings serve as visual narratives, and were often commissioned by prominent Tibetan masters to illustrate historical developments. They commonly include captions that identify specific scenes, and were often the visual renditions of written biographies (namthar) of lineage masters and important teachers of their tradition. The teachers were usually depicted with iconography similar to the Buddha’s. In the paintings, their figures are larger than the others, with hand gestures that symbolize their enlightened status or their role as teacher, and implements that identify them as emanations of . Depictions of life stories of masters probably make up the majority of Tibetan narrative paintings, and the manner in which these narratives are presented, perceived, and maintained is as varied as the paintings themselves. Nepalese masters likewise were celebrated for their achievements.

Indian who were invited to Tibet, such as Padmasambhava and Shantarakshita, were among the sources of many teachings and their lives were illustrated and tied into the Buddhism’s flourishing in the Himalayan and Tibetan regions.

Padmasambhava and his eight manifestations; Kham Province, Eastern Tibet ; 19th century; Pigments on cloth; 27 × 21 1/2 in.; Rubin Museum of Art, Purchased from the Collection of Navin Kumar, New York; C2005.35.1

Indian Master Shantarakshita (Active 8th century) and Scenes From His Life; Tibet; 19th century; Pigments on cloth; 72 × 41 1/2 × 1 7/8 in. (182.9 × 105.4 × 4.8 cm); Rubin Museum of Art, From the Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Walter Warren Wilds; C2007.22.1 (HAR 65798)

Iconographic elements, such as mudras and body posture are often direct references to pivotal moments in the life story of the depicted subjects. The Buddha’s touching the gesture referring to the moment of his Awakening and Victory over Mara. Tantric master Virupa’s raised hand to stop the sun illustrates his display of powers in the famous story from his life.

Buddha Shakyamuni; Tibet; 15th century; Gilt copper alloy; 7 3/4 × 5 7/8 × 4 7/8 in.; Rubin Museum of Art, Gift of Shelley and Donald Rubin; C2006.66.656 (HAR 700092)

Virupa; Sakya Monastery; Tibet; ca. 1216–1244; distemper on cloth; 22 × 19 5/8 in. (55.9 × 49.8 cm); The Kronos Collections; photograph by John Bigelow Taylor

Popular Narratives Permalink

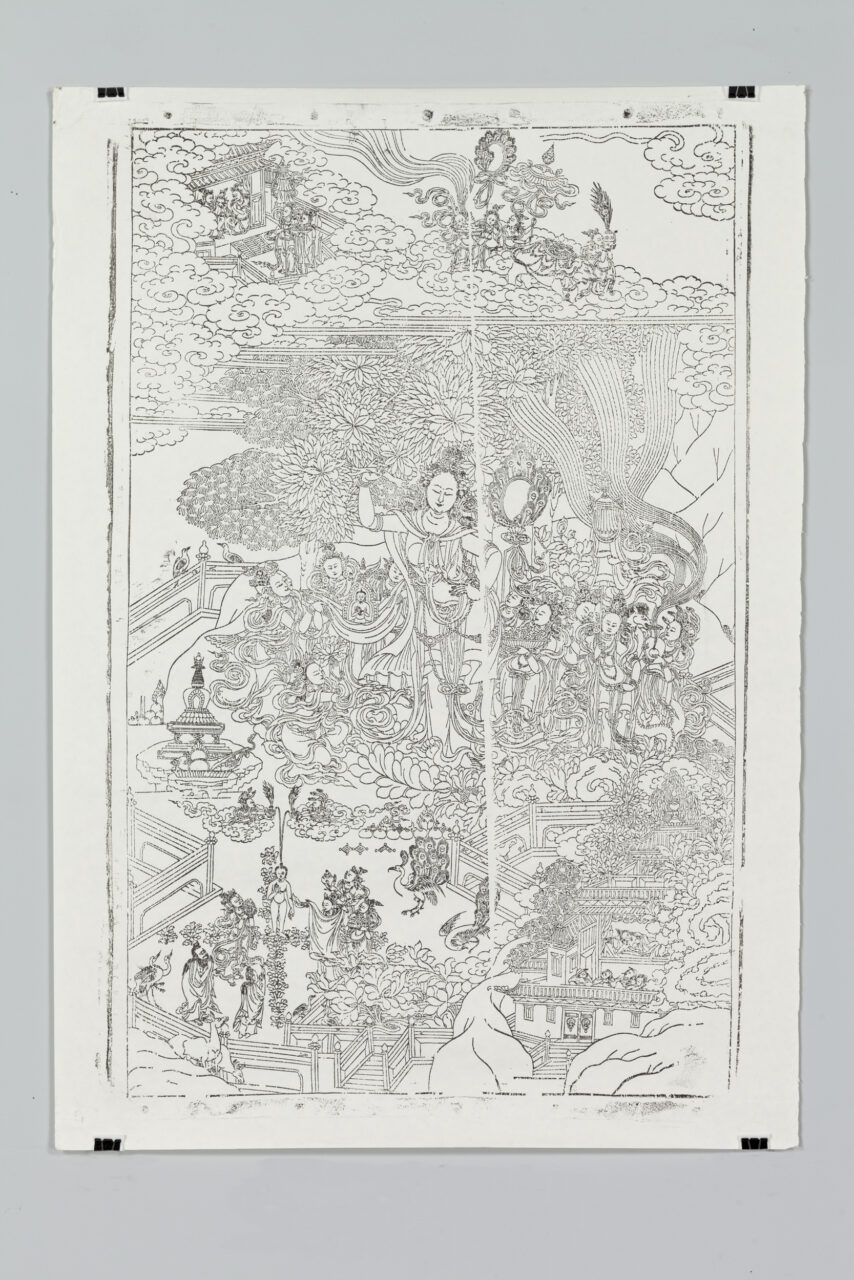

Popular narratives, such as stories adapted from Buddhist narratives, or legends about people whose lives were so memorable they inspired storytelling and even opera performances are often depicted in murals, portable hanging scrolls, and often accompanied by itinerant story-tellers’ narrations.

Storytelling is a main means of teaching in Buddhist cultures and includes legends, life stories of the Buddha, famous masters, as well as lay practitioners. The stories, visual and written, are meant to inspire and help travel the path the Buddha presented during his legendary life.