2017 marked 10 years of Brainwave at the Rubin. The popular program aims to deepen understanding of our shared human experience by turning to neuroscientists and leaders inspired by the themes from the art in the Museum’s collection.

To reflect on a decade of unique talks and experiences, we turned to the mastermind behind Brainwave, Tim McHenry, the Rubin’s director of programs and engagement.

Tim McHenry: When I first realized there was something to be said for intersecting Western-based neuroscience with Buddhist principles of understanding, I initially had just conversations in mind. But it’s the interactive experiences that stand out and have become integral to the series since its inception.

In the first year, packing a 50-year-old Dutchman in ice cubes for a record-breaking 72 minutes outside the doors of the Museum was a test not only of endurance but of the ability of someone not studied in tantra to demonstrate the effectiveness of tumo meditation. Then bouncing back onstage afterward, Wim Hof had us all grip an ice cube until it melted. That was cool.

During the second season, in a discussion about anger management, Lewis Black introduced more four letter words—in his own inimitable and explosive way—on the Rubin’s stage in one session than I thought possible. I venture to say that Mark Morris—in his own inimitable and charming way—easily broke that record the very next year.

In the third year, we premiered a Rubin Museum-commissioned work from Sir John Tavener that was performed on all levels of the spiral staircase. The audience was seated in clusters in the galleries facing away from the music. The performance, Towards Silence: A Meditation on the Four States of Atma, was prefaced by a conversation about the way the brain perceives time and death. Critic Matthew Gurewitsch wrote, “After what seemed like a pleasant eternity, there was scattered applause, but not much. Silence was the greater tribute—silence that was as full, as peaceful, and as alive as the music. In no hurry, the audience rose and followed the musicians to the lobby, speaking in hushed tones or not at all.”

One night during the fourth year, we started at 6:00 PM with Amy Tan onstage to talk about her creativity and dreams, and ended at 10:00 AM the next morning after having debuted the first ever Dream-Over. That’s where folks came to the Museum in nightgowns and fluffy bedroom slippers to sleep in the galleries for “a blind date with the art.”

In the fifth season, a hundred visitors stood single file on the steps of the Rubin’s signature spiral staircase to test not only our ability to communicate but also our short-term memory in a game-of-telephone-like “karma chain.” Broadcaster Jane Pauley whispered a phrase into the ear of the first person on the stair till it reached the ear of neuroscientist Sebastian Seung. What he had heard was: “There are no drugs allowed, just lies.” Jane doubled over and guffawed at the garbling, because the phrase was drawn from the last line of her own book Skywriting, “There are no charmed lives, just lives.”

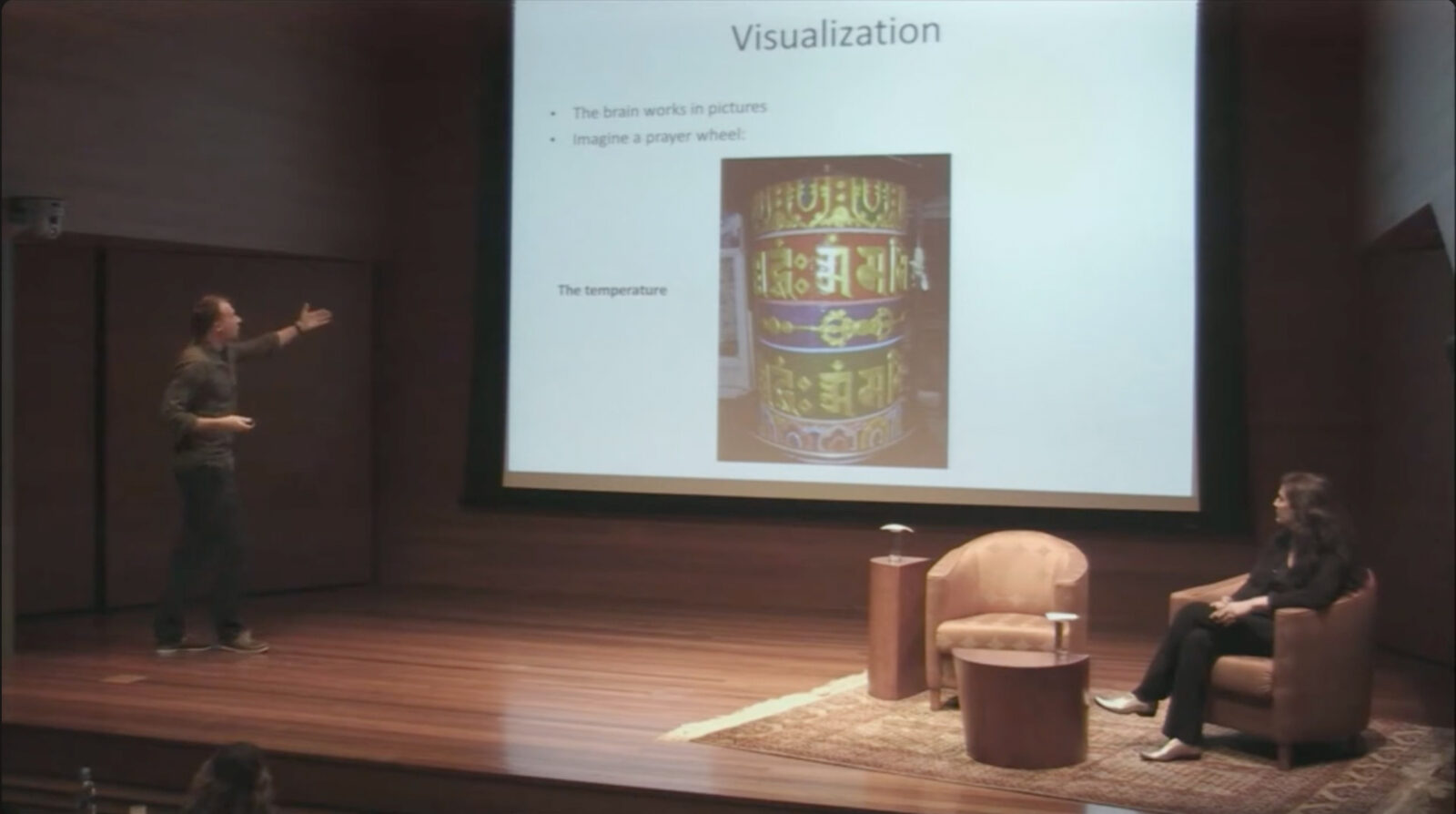

In season six, mountaineer and US memory champion Nelson Dellis tested our ability to acquire and retain 64 separate facts within the space of 64 minutes. Two of the workshoppers succeeded with a 100% score.

In the seventh year, the snappy dresser and basketball champ Walt “Clyde” Frazier admitted that yoga had kept him attuned to his skill all those championship years.

In season eight, Jake Gyllenhaal revealed one of his dreams.

In season nine, my long-held desire to pair Stephen Sondheim and Steven Pinker became a reality. After Professor Pinker launched into his rendition of “Hey Officer Krupke” there was no holding back. It was one for the ages.

In being allowed to taste Lidia Bastianich’s classic marinara sauce while she and Dr. Gary Beauchamp were analyzing it onstage, we also came to understand the motivation behind her culinary empire: refugees from Tito’s Yugoslavia: “That moment I realized I wasn’t going back and I hadn’t said goodbye to my grandmother. Food became my link and my emotion. I needed to place myself in that comfort place. Food is love and connection. A way of saying goodbye. I feel best when I can nurture something.” And in Lidia Bastianich, what a great example of the value that refugees from different cultures bring to this country.