Sarah Zabrodski: From the perspective of your profession, how would you define interdependence?

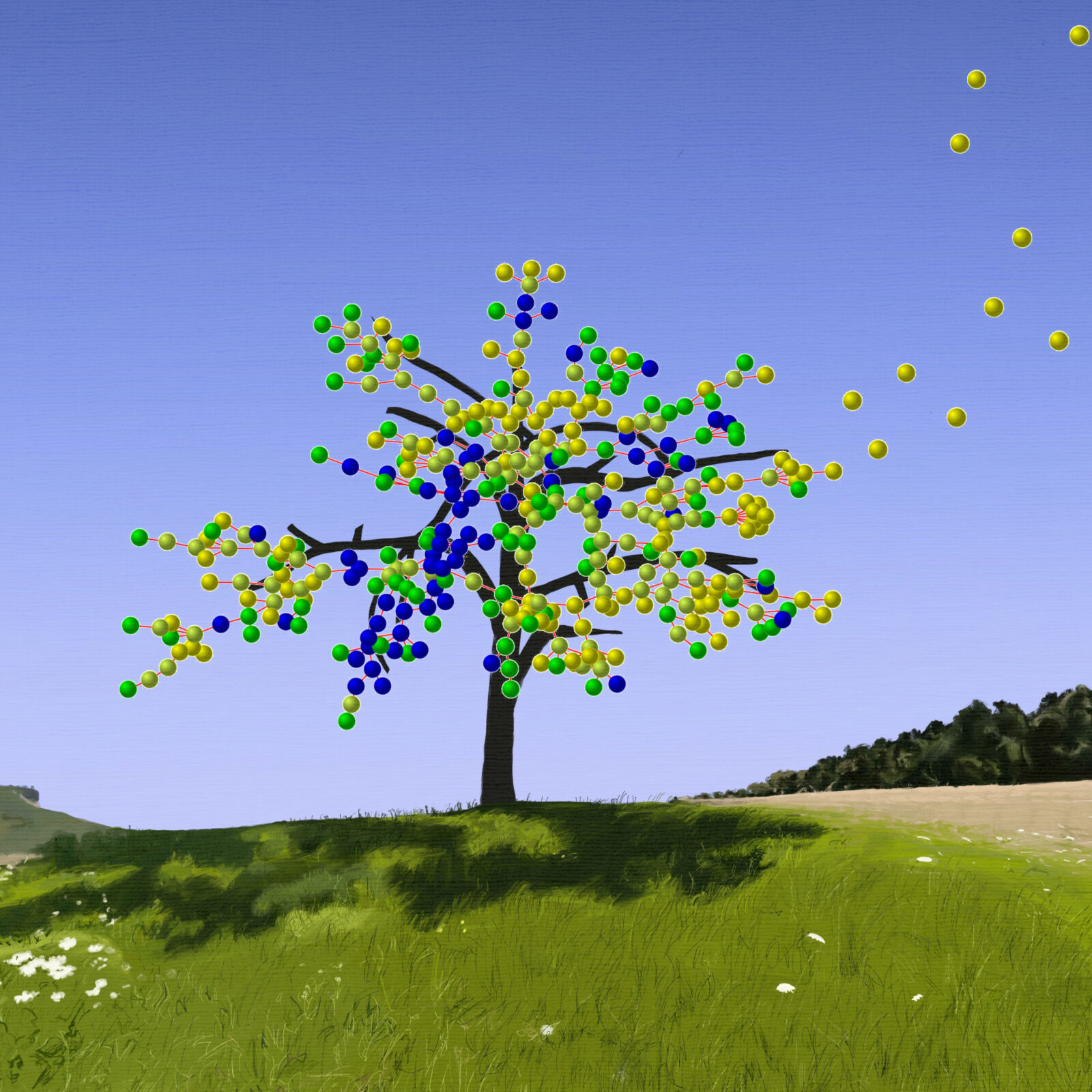

Nicholas A. Christakis: I’ve spent the last twenty-five years studying complex social networks. They are intrinsically an interdependent structure. Each of us inherits our relatives, picks our friends and coworkers, and all of those people in turn are picking or inheriting other people as connections. We therefore proceed to assemble ourselves into this large, interdependent, beautiful, baroque, organic structure known as a social network.

And your fate and life depends, to some material extent, on where you are in such a network. Anyone can understand this, nowadays, because of our recent experience with the pandemic. Whether you get COVID depends, for example, not just on your own actions, but the actions of your friends and the actions of your friends’ friends and the actions of your friends’ friends’ friends.

Our fates are connected to the fates of others, including people we don’t even know. And this interdependence can be understood using a variety of scientific tools from biology, psychology, sociology, physics, and mathematics, because our social networks obey very particular (and scientifically intelligible) rules.

Could you speak about the scientific principle of emergence and how it is related?

Emergence is the idea that collections of things can have properties that are not intrinsic to the thing itself. The simplest example is carbon. You can take carbon atoms and combine them one way, and you get graphite, which is soft and dark. Or you can take the same carbon atoms and combine them another way, and you get diamond, which is hard and clear. There are two key ideas here. First, these properties of softness and darkness and hardness and clearness are not properties of the carbon atoms. They are properties of the collection of carbon atoms. And second, which properties you get depends on how you connect the carbon atoms to each other.

That’s emergence—that these new properties arise because of complexity, because of interdependence, because of interconnection. It’s a magnificent phenomenon in nature, not just restricted to chemistry or biology, but also relevant to our social lives.

I think most people are familiar with how strangers can impact us when it comes to contracting a virus. How do people we don’t even know influence us in ways that we might not realize?

Over the last twenty years in my lab, we’ve done a lot of studies of this, including large-scale experiments in online settings, as well as in public health settings around the world. Initially, we did observational research. We studied, using mathematical and statistical tools, naturally occurring systems. We found, for example, that your body size depends, to some extent, not only on your own choices and actions, but also the choices and actions and the body size of your friends, and your friends’ friends, and your friends’ friends’ friends. Also, we found that how happy you are can depend on where you are in the network and the state of happiness of other people, including not only the people you are directly connected to, but even people you don’t know and are only indirectly connected to.

Those are examples of things that can spread by a process of social contagion within social networks. But it’s very difficult to know for sure that that is what’s happening when you use observational data. To really be certain, you have to do experiments.

What kinds of experiments can be done?

Beginning in 2010, we started doing experiments with tens of thousands of people online and in settings around the world, from Honduras to India to Uganda. For example, you can bring people into a laboratory setting, randomly assign them to groups of four strangers, and have them play something known as a public goods game. In such a game, each person has some money. If I give one dollar to the group of four, that one dollar is doubled and then it’s divided among the four people. The group as a whole has gained two dollars from my one dollar contribution, but then that two dollars is divided four ways and comes back to each person, so I only get back fifty cents. The group benefits, but I pay a price.

Most people might expect that nobody will contribute. From an individual, selfish point of view, the smartest thing to do is give nothing and hope that everyone else contributes. Of course, if nobody contributes, the group collapses. But the best outcome is if everyone contributes maximally. And, indeed, most people are kind and do contribute, and they have some realistic expectation that others will reciprocate.

In that first experiment, people played this public goods game across multiple rounds. A bell would ring and they would play with new strangers, and then ring again and they would play with new strangers. We were able to show that if Tom was kind to Dick in round one, Dick would be kind to Harry in round two, Harry would be kind to Betty in round three, and Betty would be kind to Susie in round four. So how Betty treated Susie depended on how Tom treated Dick, even though neither Betty nor Susie ever saw or interacted with Tom or Dick. We were able to experimentally demonstrate the social contagion of goodness, spreading through a network.

Are there experiments that show how this can play out in the real world?

In other experiments, we mapped the social networks of 24,000 people living in 176 isolated villages in Honduras, who we followed for eight years. We randomly chose certain people in the network, according to certain mathematical algorithms, and we taught them things relevant to maternal and child health, like breastfeeding, vaccination, and so on. We were able to artificially create cascades of the contagion of this desirable knowledge in these isolated villages, improving the health of everyone in the village, not just the subset of people selected to get the knowledge directly. We have also done similar work in India.

In short, both observationally and experimentally, over the last twenty years, we have been able to show that social contagion is an important factor in our lives. How you act, what you know, and how you feel depends on your embeddedness in the vast fabric of humanity.