Muna Bhadel; Mute Melodies; 2023; acrylic on canvas; courtesy of the artist

Muna Bhadel; Mute Melodies; 2023; acrylic on canvas; courtesy of the artist

Muna Bhadel was born in Changu Narayan, Bhaktapur, in 1989. The city of Bhaktapur is known as a city of “Bhaktajans” or devotees. For centuries the men of the Bhadel family have served as assistants to the Rajopadhya priests at the glorious Changunarayan temple, which is dedicated to Lord Vishnu. This temple, built in the fourth century by Lichhavi King Man Deva, is one of the oldest temples in the Kathmandu Valley.

The Bhadel family has resided in their ancestral home, close to the Changunarayan temple, for hundreds of years. In this household, where devotion is part of everyday life, Muna’s father, Narayan Bhadel, chose a different course and studied art at the Lalit Kala Academy of Fine Arts. After receiving his BFA, Narayan taught art at Umahangma English School in Bhaktapur for five years. In 1997, Narayan met with an accident and tragically passed away—he was just 31 years old. Muna’s mother, Tej Kumari Bhadel, now had the daunting task of raising four children alone.

In the void left by her father’s death, Muna remembers the care and support her family received from her maternal and paternal grandmothers. Muna, who was nine years old when he died, recalls his love and dedication to the arts. After graduating from Basu Secondary School in Bhaktapur, Muna decided to follow in her father’s footsteps and enrolled in the Lalit Kala Academy of Fine Arts in 2006.

Muna Bhadel; Lost in Reflection; 2024; acrylic on canvas; courtesy of the artist

In an Online Khabar interview with arts writer Sangita Shrestha from August 2022, Muna shared, “Relationships and interactions with your loved ones mold your character, behavior, and overall personality. They are also decisive in how you get attached to your loved ones over the course of time. Whether it be literature or art, family background and the way one is brought up usually get reflected on their work.” The impact of Muna’s grandmother on her life and work has been powerful and overarching.

Muna’s 2024 exhibition Silent Whispers at the Siddhartha Art Gallery took on several dimensions. What do the whispers allude to? It could be the connection between a father and daughter and the unspoken connection between the two artists. Yet the paintings and drawings lay bare multiple emotions. What comes through is the tendresse that inspires the artist, and how she has placed care and kinship at the center of her work. This tendresse is accentuated in the aftermath of the great earthquakes in Nepal in 2015 and the onset of the global pandemic in 2020.

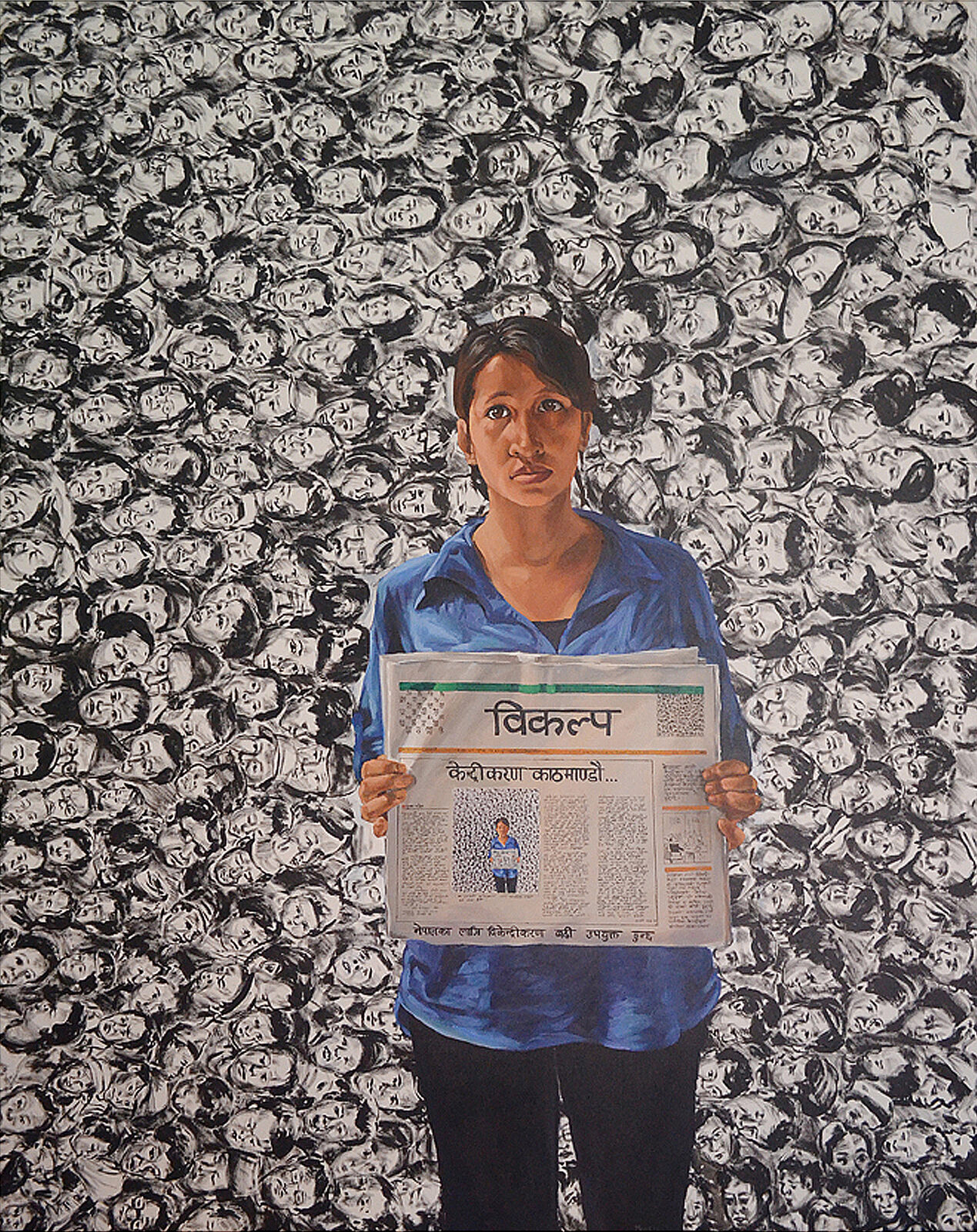

Muna Bhadel; Dentralization; 2013; acrylic on canvas; courtesy of the artist

Muna’s earlier work is politically tongue-in-cheek. The painting Decentralization was part of the United Nations Development Programme that encouraged artists to explore the sociopolitical dimensions or potential impact of federalism in Nepal after the initiation of the new constitution. Instead, Muna painted herself holding a daily newspaper with a satirical masthead: bikalpa, or “alternative.” The headline of the article reads “Centralized Kathmandu.” In a mise en abyme, the front page of the newspaper features the same portrait as the overall painting, with a multitude of curious and expectant faces surrounding her. Thus Muna becomes one with the masses. This work interrogates Nepal’s sociopolitical experiment with federalism and questions if “power” can be decentralized from Kathmandu.

In 2015, several earthquakes struck Nepal with tragic consequences. Some artists lost their loved ones, some saw their homes or studios destroyed, and some sustained injuries. In response to this situation, Siddhartha Art Gallery and Kathmandu Contemporary Arts Centre provided three artists—Muna, Jeewan Suwal, and Sandhya Silwal—a safe space in the garden studios at Patan Museum. Later the three artists showcased the outcome of their residency at the Siddhartha Art Gallery. The works Muna created in this period, the Come Back Home series, portray the vulnerability that older women in the community must have felt after being displaced from their homes, yet their wrinkled faces still reflect resilience in the face of calamity.

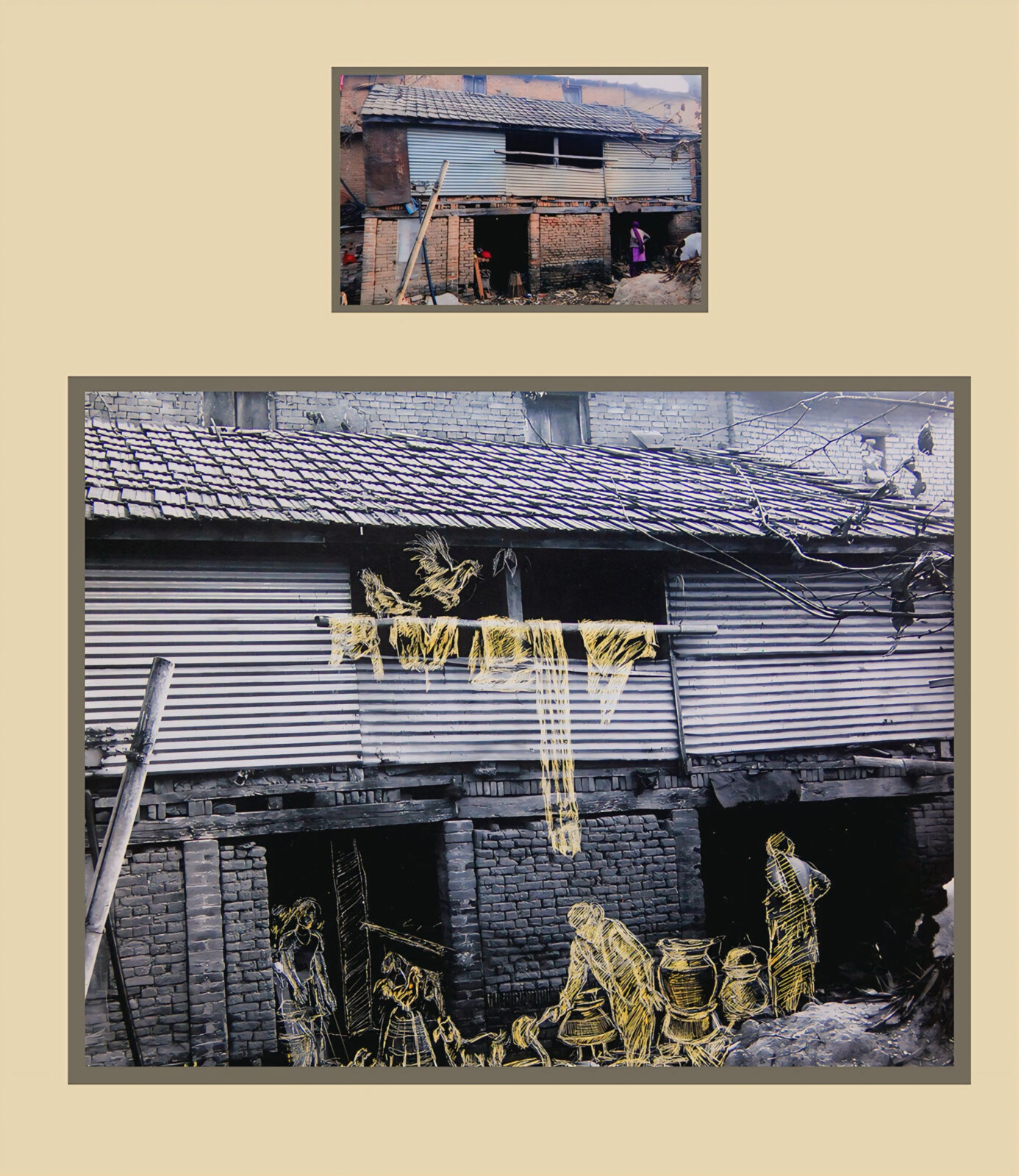

Later that year, Muna graduated from Lalit Kala Academy and joined a master’s program at Tribhuvan University. From 2016 to 2017, she was a resident artist at Taragaon Museum. The resulting body of work, the Missing Souls series, is dedicated to the memory of Dapcha, an old bazaar town perched on a hilltop in Namo Buddha Municipality, where the artist spent time as a child in her maternal grandmother’s home. These mixed-media works reveal Muna’s capacity to research, experiment, and deliver a poignant testament to the loss of heritage and displacement caused by the earthquakes and the impact of migration on this quaint town, which once served as a trade route to Kathmandu. Above all these works pay homage to the artist’s matrilineal identity and the place where a granddaughter bonded closely to her grandmother.

Muna Bhadel; Now where to be found; 2019; scratch on photograph; courtesy of the artist

In 2018, Muna received her MFA from Tribhuvan University, and a year later she married the artist Anil Shahi. The specter of the earthquakes continued its hold on Muna’s psyche and is evident in a series from this period. The drawings depict traditional Newar buildings ravaged by the earthquake. The titles go beyond the physical destruction of the buildings to poignantly address how concepts of family, home, shelter, and community were at peril. Muna’s use of turmeric color in her drawings not only reflects the plant’s history as an organic pigment used by artists of the past but also its use for healing in traditional Ayurvedic medicine.

In 2020, the global pandemic, with its impact on families and the elderly, prescribed isolation, and deaths, deeply affected the artist. The physical and mental trauma of this period anchored the next direction of her work. Narratives of care become an integral theme. The story of her grandmother in particular seems to have sensitized the artist to the plight of elderly women.

The painting Memory Lane features the grandmother’s clothed back facing the viewer. Her solid, stoic form is set against the patterns on her traditional dhaka blouse, auspicious red sari, and red flower tucked into her bun, as she gazes or stumbles upon a scene from a distant past. This scene references traditional Nepali paintings that Muna has seen in Patan Museum and Bhaktapur Museum and from books on Nepali painting and Newar art. These early paintings evolved with influences from India, mainly Rajasthani, Pahadi, and Mughal schools of art. By referencing these elements, Muna expresses a layering of history, not only in the evolution of Nepali painting but also its legacy and connection to her work. The figure of Muna’s grandmother set against a historical backdrop where women revel in their youth and moments of intimacy creates a powerful juxtaposition.

Between 2021 and 2023, Muna made a series of portraits of women. The artist explored a feminine sensuality that is subtly expressed through clothing and textiles, which not only represent our inherent materiality but also acknowledge the emotional connections that people have always had with textiles. In the Sangita Shrestha interview, Muna remarked that our clothes “remind us of special events in our life as well, which sometimes become a way to communicate with new generation about our memories and be nostalgic.”

Muna Bhadel; Correlation Between Us II; 2022; acrylic on canvas; courtesy of the artist

One painting in the series features a young woman with a serene gaze, her back bare, while the rest of her body is sensuously swathed in a luxurious textile. This painting was exhibited at the annual Himalayan Art Festival and expanded into a larger, colorful body of work titled the Correlation Between Us. In this series, the women continue to revel in the sumptuous folds, drapes, and colors of textiles, in patterns derived from traditional dhaka fabric and paubha paintings. Once again Muna juxtaposed images from the past with contemporary portraiture. The images of the women from the past show the same emotions and actions as the women from the present. In these works, a woman’s hair is an extension of her sensuous self, and the mirror serves as a vehicle for a woman to realize her power and beauty.

The series is also a celebration of femininity. As the artist said in the Sangita Shrestha interview, “Feminism also means accepting who you are and loving yourself. So, I am admiring all the qualities of being a woman who is soft yet powerful.” In an article in the Kathmandu Post, Isabel Iwin observed, “Through her art, Bhadel emphasizes the importance of understanding and learning from the older female generation’s experiences. . . . Her art memorializes personal histories rather than advocating for an avenue for societal change.”

The idea of care is evident in a series of monochromatic drawings of intertwined hands in different positions. The artist used red pigment to establish the blood relationship with her grandmother. In the drawings, Muna clasps her grandmother’s wrinkled hands in her own, symbolizing love, trust, and tendresse. Beyond the care aspect, the hands also represent the time past embracing the present and future unconditionally.

Muna Bhadel; Custodian of Fate; 2024; acrylic on canvas; courtesy of the artist

In 2022, Muna gave birth to her first child, and her grandmother passed away. The works in Silent Whispers are a labor of love and a deeply personal homage to the grandmother. Muna references the art of the past to signify the separation between the grandmother’s nostalgia or dreams and status as an older woman. While the grandmother is depicted in a hyper-realistic style, the rest of the composition references and conjures historic art.

Muna’s paintings reflect her observations about the cycle of birth, life, and death, and of youth with all its beauty and seductions. In her article about the exhibition, Isabel Irwin wrote, “In a world shaped by technological advancements and shifting societal norms, traditional roles of women as primary caretakers have undergone significant transformation. This shift is vividly captured in the artistic practice of Muna Bhadel, whose paintings reflect her grandmother’s life and the broader implications for women in Nepal . . . . [Muna] has experienced many freedoms that her grandmother had not—falling in love and pursuing her artistic career.”

The anointing of a woman’s hair and feet is an intrinsic part of the sora singaar (bridal adornments) and is a symbol of youth, marriage, and sensuality. Yet in Muna’s works, this act of anointing is also imbued with multiple narratives about loss and aging, care and lack of care, kinship, community, and loneliness, unfulfilled dreams, nostalgia, isolation, and longing. The aging women in these paintings seem trapped in the cage of filial duty, in a society and time when women were bound to their homes.

The show includes a set of 10 drawings of hands. These hands are juxtaposed against fragments drawn from historic paintings that symbolize a woman’s eternal relationship to nature and the cycle of life.

The artist also created a set of four paintings inspired by patachitras (traditional scroll paintings), called bilampau in Newari. The artwork Age of Grace celebrates the grandmother’s janko ceremony, which occurs when a family member reaches 77 years, 7 months, and 7 days. By juxtaposing and weaving these traditional elements in her paintings and creating a dialogue between the past and present, Muna pays homage to her Newar heritage.

Though this coming of old age is celebrated, Muna’s portraits of her grandmothers are hardly jubilant. Instead, they express the sometimes harsh reality of the elderly and make a powerful statement about care and community in a modern context where the extended family is replaced by a nuclear family and women have joined the workforce. These changes will most definitely impact the elderly as geriatric care is practically nonexistent in Nepal. Muna’s paintings therefore hold a mirror to society, urging us to look at how families and the state will care for the elderly in our “modern” Nepal mandala.

Sangeeta Thapa established the Siddhartha Art Gallery in 1987. She served on the board of the Patan Museum and is a fellow of the De Vos Institute of Arts Management. In 2009, she launched the Kathmandu International Arts Festival (KIAF) as a triannual event that later transitioned into the Kathmandu Triennale. In 2011, Thapa set up the Siddhartha Arts Foundation as a nonprofit organization to manage KIAF and train the next generation of arts managers and leaders. In 2022, Siddhartha Arts Foundation served as co-commissioner of Nepal’s first pavilion at the Venice Biennale. The President of Nepal awarded Thapa the Jana Sewa Prabal medal for her contributions to the field of Nepalese art.

Get the latest news and stories from the Rubin, plus occasional information on how to support our work.