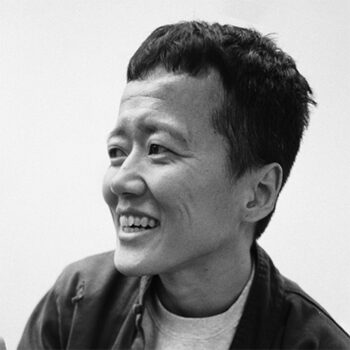

Illustration by Tenzin Tsering

Illustration by Tenzin Tsering

Growing up, I was a youth with a soft voice who used the women’s restroom. It was the restroom society had assigned me. In it, I found myself repeatedly targeted by women who deemed me an unfit member of their group.

When I was born in South Asia in 1984, families like mine were permanently designated as refugees. Lacking a path to citizenship, my parents were motivated to try and raise me elsewhere. My mother wanted me to grow up in a society that prioritized equality, and she was especially fierce in her expectation that I not be dehumanized or discriminated against on the basis of my gender.

We reached the United States in 1989. Through my parents’ sacrifices and the opportunities for equality created through the Civil Rights Movement, I became a US citizen in 1996 at the age of twelve.

I was seventeen when I began experiencing regular harassment in the women’s restroom. My boyish appearance sometimes startled people. I navigated these encounters by smiling, speaking up, and offering identification if it came to that. I grew to observe that the sound of my voice was enough to dispel apprehension. Unfortunately, some women then chose to extend the interaction, despite knowing our bodies shared similar content. They would ridicule me, follow me, point me out to others, touch me, threaten me, and otherwise humiliate or hinder me.

Harassment is a decision, not an involuntary reaction. The women who treated me this way were making a statement about social membership. They viewed me as an unacceptable version of their gender, and therefore unentitled to share space with them.

During the time of these incidents I viewed myself as genderqueer or what could be described as non-binary, but the law held no protection for this identity. I crossed the legal threshold between woman and man in 2010, at age twenty-five. I chose what felt right to me, and I’m grateful to earlier generations who endured violence and exerted effort to create this option.

Upon learning of my decision to begin hormone therapy, my mother first responded with concern that I might get sick from the medication. Neither of my parents were used to medications or receiving physician care. I reassured her I was not harming myself and that being able to make these changes would bring me deep personal fulfillment.

Four years later it was 2014 and US society was talking openly about what had always been in its history—the existence of transgender people. Laverne Cox, a Hollywood actress and Black transgender woman, was the face of the story Time magazine called “The Transgender Tipping Point.”

“Some folks, they just don’t understand. And they need to get to know us as human beings,” she says. “Others are just going to be opposed to us forever. But I do believe in the humanity of people and in people’s capacity to love and to change.” —Laverne Cox

My working-class Tibetan parents, immigrants from recently colonized Tibet, could have dismissed my gender transition as something unworthy of taking seriously. Instead, they drew upon decades of experience as refugees to understand the indignities and risk in store for me as a transgender person.

They are both intimately familiar with what it means to be legally and socially vulnerable—to have your paperwork and identity over-examined and easily rejected. And although they didn’t know the specifics of my experience, my parents were familiar with the positive effects of love. They continued offering it to me without condition and chose to affirm my transition. In doing so they benefited my spirit tremendously.

My mother, who calls herself an uneducated and practical woman, recognized my differences early on. Seeing the pain I felt in “girls” clothing, she shielded my self-expression from others’ judgment and allowed me to grow.

“I don’t ‘try’ to love you or ‘try’ to accept you. If I did this it would not work well for me. Whether you are lesbian, or gay, or transgender, I just love you,” she said in a phone call with me in 2016. “I choose you. You didn’t get to choose me. I had a choice.”

My father has also set a standard of care by not treating his support of me as a favor, but rather as a responsibility and joy. “Children are a parent’s adornment,” he once told me. “Just by existing, you add beauty to our lives like an ornament or jewel.”

My parents’ embrace of my transition reminds me of something a Korean American psychology professor shared in an interview I conducted as an undergraduate. She said that when her LGBT students shared the pain of their identity and experience, she did not understand that specific pain. But she did know the pain of being a woman, of being an immigrant and a person of color. “I do know something about pain,” she said. “And it is from this place I can listen and learn.”

This professor used her identity and experience as a cisgender woman to connect with others, not exclude them. I hope more people do the same.

Our shared quality of life is linked to policy as much as individual acts. As the US looks into whether it will grant my community full membership, I would like to speak to the reader who has a vote in this debate.

Some people like to act as though transgender and non-binary are made-up identities. Influential figures treat us as objects of derision and harbingers of danger. But all our existence does is point to the fact that there is more to gender and sex than you might think. The world is not flat—it has depth. It always has.

Those who are not interested in our equality resort to dehumanizing tactics. They pick apart our bodies whether we are young or old, and insist that no matter what chromosomes cannot be changed.

History can’t be changed either. But that’s why we have things like healing and justice; because we deserve the chance to change from our past. To know what life after might be like.

Tenzin Mingyur Paldron (he/they) is an artist, storyteller, and community educator. He has a PhD in rhetoric from the University of California, Berkeley and wrote the dissertation “Tibet, China, and the United States: Self-immolation and the Limits of Understanding.” Paldron is developing multimedia projects such as Tibet Learning Series, Transgender Learning Series, and Ethical Mindfulness. They are also writing a research memoir entitled Transgender Road Diaries: A Tibetan Adventure. He shares these projects through public speaking engagements as well as on his YouTube channel, @DocTenzin.

Get the latest news and stories from the Rubin, plus occasional information on how to support our work.