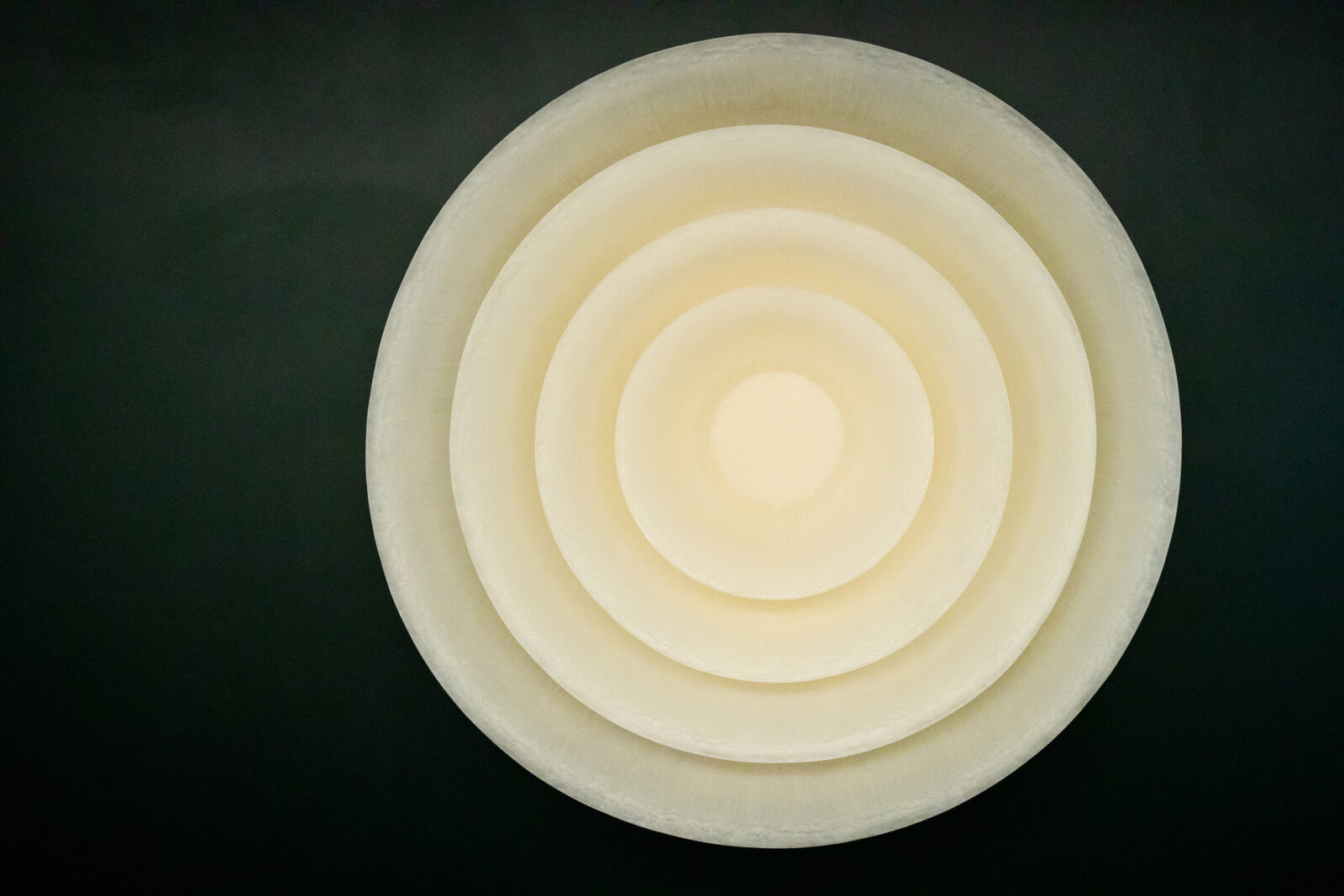

Palden Weinreb (b. 1982, New York, NY; lives and works in New York, NY); Untitled (Coalescence); 2021; PU resin, LED lights, microprocessor; Rubin Museum of Art; C2021.1.1; courtesy of the artist. Photograph by Liz Ligon.

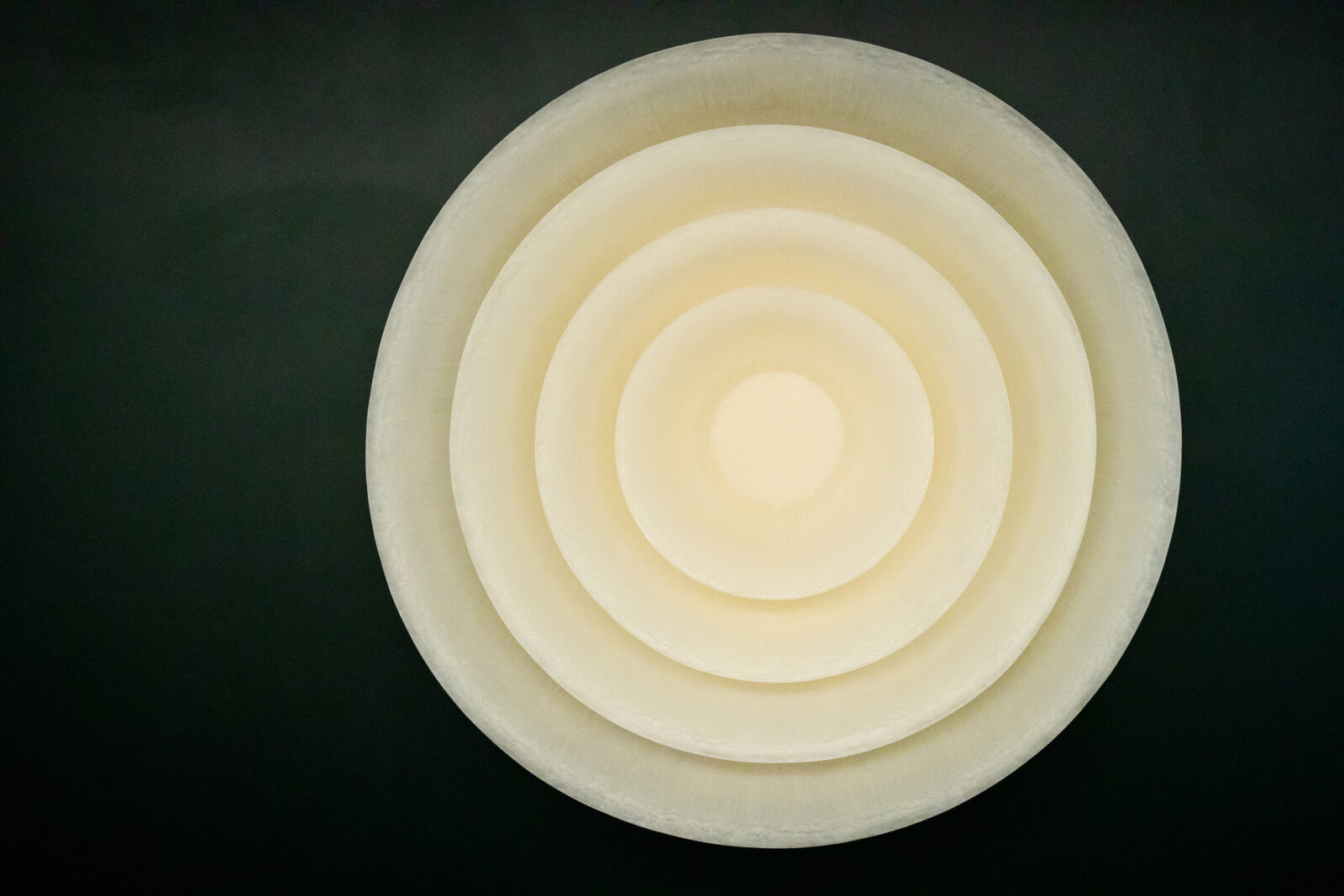

Palden Weinreb (b. 1982, New York, NY; lives and works in New York, NY); Untitled (Coalescence); 2021; PU resin, LED lights, microprocessor; Rubin Museum of Art; C2021.1.1; courtesy of the artist. Photograph by Liz Ligon.

It seems to me, the nose is having a moment.

Classes on mindfulness and breathwork offer transformational experiences through the simple act of inhaling and exhaling, while James Nestor’s book Breath—a how-to and how-not-to guide about breathing (nose breathing for the win!)—hit the bestseller lists.

Breathing. We all do it, but are any of us doing it well? From the first breath we take till our last, our minds and bodies run on fuel supplied by a combination of oxygen, nitrogen, and other assorted gases. And since breathing comes automatically (though with more difficulty if you have asthma or a lung disease), what would happen if breathing became more mindful, more purposeful?

Breath is at the heart of the Rubin’s Mandala Lab, a reinvented space on the Museum’s third floor, where visitors see, touch, feel, and yes, breathe their way toward self-understanding. This interactive installation draws on Tibetan Buddhist teachings and neuroscience to provide sensorial experiences that help us gain deeper knowledge of ourselves and others, inspiring connection and empathy. In turn, this helps us overcome the afflictive emotions of pride, attachment, envy, anger, and ignorance—known as kleshas in Buddhism—that interfere in our understanding of the world and cause suffering.

The installation comes at a time when our country is experiencing the concurrent pandemics of systemic racism and COVID-19. In 2020, George Floyd told officers, “I can’t breathe,” more than twenty times while begging for his life. The coronavirus has filled emergency rooms with people who are fighting for their breath and need to be placed on ventilators. And the politics behind the virus have deeply divided us, revealing more than ever the need to come together as communities and as a nation. As we know from experience, a divided nation will not stand; success occurs when we work in concert with others.

When you enter the north quadrant of the Mandala Lab—which is associated with the air element—you’re invited to sit in front of Untitled (Coalescence), a sculpture by Palden Weinreb, a New York–based artist who draws from Buddhist teachings and combines the ancient and the contemporary in his art practice. A pulsing white light brightens and dims to echo our breathing patterns, encouraging deeper, more thoughtful, slower breaths. Can these regulated breaths have physical, psychological, and emotional benefits?

The sculpture seems to function as a mandala within a mandala, as the light sits in the center of a series of nested spheres, much as a deity is represented in the middle of sacred diagrams. At once you begin to inhale as the light increases, then exhale as the light dims. One cycle lasts about eleven seconds (10.73 seconds to be precise), with approximately five seconds in and six seconds out, the most effective mind-body rhythm.

“The piece invites a meditative experience that encourages viewers to delve into their own thoughts,” Weinreb explains. “While this sets the stage for a multitude of interpretations that align with the concept of a mandala, the pulsating light acts in a continuous cycle to draw viewers into contemplation and separate themselves from their surroundings,” he adds. “Much like a mandala, the light flowing through the sculpture could be seen as an instrument for meditation, setting the stage to invite the pursuit of enlightenment.”

This section of the Mandala Lab invites you to think about envy and how it affects your treatment of others. Being covetous of somebody else’s success or material gains will not do much for you. Buddhist practitioners work to replace envy with positive actions that contribute collectively to a greater good. According to psychologist and neuroscientist Richard J. Davidson, founder of the Center for Healthy Minds at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, connection is one of the pillars of a healthy mind. What if we used our breath purposefully to elicit a feeling of connection with others? When multiple people participate in this section of the Mandala Lab, you get to see this idea in action.

Palden Weinreb (b. 1982, New York, NY; lives and works in New York, NY); Untitled (Coalescence); 2021; PU resin, LED lights, microprocessor; Rubin Museum of Art; C2021.1.1; courtesy of the artist. Photograph by Liz Ligon.

Inevitably, there comes a moment when everyone in the installation is breathing rhythmically to the same light pattern, the same amount of seconds in, the same amount of seconds out—a synchronized union among disparate strangers. When everyone is doing the same thing, you recognize that you’re no different than the person beside you or across the room. And if we’re all the same, how can anyone be jealous of anybody else? In this way, slowing down the breath and syncing up with others may help us cut down on envy and add a little more equanimity to our lives.

James Nestor’s book Breath: The New Science of a Lost Art could be considered the bible on breathing. His journey to discovering the benefits of nose breathing and the hazards of mouth breathing (snorers, take note) takes him to Stanford University for observation, and it even involves sleeping with his mouth taped shut to prevent him from using his mouth to breathe. Breathing through the nose allows air to be warmed while also removing impurities. As a bonus, nose breathing activates nitric oxide, which releases oxygen, which is beneficial for our bodies. Mouth breathing does not.

Nestor wasn’t the first to discover the positive effects of nose breathing and its offshoots including alternate nostril breathing. In fact, the lost art he references in the book’s subtitle has a long history; breath has been a part of yogic practices and world religions including Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam, and Christianity for millennia. Tummo breathing, for example, is an ancient meditation technique developed by Tibetan Buddhist monks.

In Tummo, a practice named after the goddess of heat and passion, practitioners raise their body temperature significantly using breath and visualization techniques. About a century ago, explorer Alexandra David-Néel visited Tibet—and is believed to be the first Western woman to have done so—and described her firsthand accounts of witnessing monks melt frozen sheets of cloth from their bodies while practicing Tummo.

In many languages, the words for breathing and spirit are the same or closely related. In yoga, breath is the tool for energy and transformational experiences, and a mindful breath is essential to Buddhist practice. I was reminded of the importance of breath in a spiritual context when taking mindful meditation classes with Lama Aria Drolma, a formally authorized Buddhist teacher and lineage holder in the Karma Kagyu tradition of Tibetan Buddhism. During sessions Lama Drolma would frequently tell us to focus on our breathing when we get distracted or lose focus. “The breath,” she said, “will bring you back.”

Lama Drolma described in a bit more depth the importance of breath in meditation. “When Buddha became enlightened, he saw that we were all interconnected, and that was the nature of all beings,” she said. “In meditation practice the breath is used as an anchor to still the mind and acts as a bridge between the mind and the body. Mindfulness meditation helps to bring our attention to the present moment by focusing on the breath and seeing what arises in the mind without judgment. When the attention wanders off, bring the mind’s attention back to the breath. When you’re swinging between past and future your mind becomes very stressful. Our breath always gives us the opportunity to connect with what is happening right now.”

Her words sound even more prescient when experiencing the Mandala Lab, focusing on Palden Weinreb’s light sculpture. Breath can bring us in contact with ourselves as well as others. I realize now how important the simple phrase “Take a deep breath” can be, whether it’s gaining focus in meditation class, navigating everyday stresses in life, comforting a friend in need, or simply returning to the present moment.

Breathing can help.

Experience the power of breathing in the Mandala Lab.

Howard Kaplan is an editor and writer who helped found Spiral magazine in 2017. He currently works at the Smithsonian and divides his time between Washington, DC, and New York City.

Rubin Museum

150 W. 17th St., NYC

Get the latest news and stories from the Rubin, plus occasional information on how to support our work.