Zhitro Mandala by Pema Namdol Thaye; © Padma Studios® 2021.

Zhitro Mandala by Pema Namdol Thaye; © Padma Studios® 2021.

Pema Namdol Thaye is an artist who makes divine structures come to life. Some of us may recognize mandalas as floorplan-like diagrams, usually rendered in paint or colored sand, which represent cosmic realms of deities. What we rarely get to see are mandalas as magnificent architectural forms of manifested heavenly palaces. Pema Namdol creates such celestial edifices. He is an accomplished traditionally trained artist of thangka painting who also perfected the exceptional art of 3D mandala making. The Rubin Museum has shown two of his mandalas in past exhibitions. Here Pema Namdol discusses his latest work and the process of bringing the rich symbolic meaning of the mandala into full view in multiple dimensions.

Pema Namdol Thaye: Art was in our family, and my teacher is my uncle, Lama Gonpo Tenzing Rinpoche. He learned this art of making 3D mandalas in Tibet. Living with my uncle growing up, I was always exposed to art, and from a very early age I was crystal clear that art was my life’s purpose. I had very little interest in anything besides art. It is beyond any doubt that it was my karma to be born in that family.

It is very rare because of the amount of time it takes to create each mandala, and it requires so many different master artists to put it together. Traditionally in Tibet, first the 3D artist has to create the 2D line drawing. Then the artist has to conceptualize everything into the 3D format, after which he works with master wood, clay, and metal carvers to build it. Finally, the artist works with painters knowledgeable about traditional architectural decorative motifs. To build a 3D mandala in the twenty-first century is rare because the tradition is almost entirely extinct. In my case, I am fortunate to have the multidisciplinary training necessary to be able to create all aspects of a 3D mandala. It is my sincere aspiration to see the 3D mandala tradition revived in my lifetime.

First you have to study a wide variety of texts of the deity whose mandala you wish to create. Then you have to visualize the deity. You have to study and meditate on the characteristics of the deity and the deity’s retinue, which will give you a good insight into what you are about to create. You have to be able to see the entire premeditated mandala, the cosmogram of the deity. After that, I wouldn’t say it’s easy, but now you’re just bringing the celestial vision into life, as material compound. It’s in your mind, and now you have to make it solid.

There’s no mandala manual text like that. You have to go to a particular deity’s sadhana, and then in the sadhana it will describe the mandala. But not all texts have detailed instructions. Some have more instructions than others. In terms of Zangdok Palri (Copper-Colored Mountain Palace), there is no one text that describes all aspects of it. There are enlightened beings who traveled there. They had visions, they astral traveled, they had dreams. Each came back with different information. So you have to read over thirty different texts and then mentally weave the information together in order to create the visual imagery of the mandala’s form.

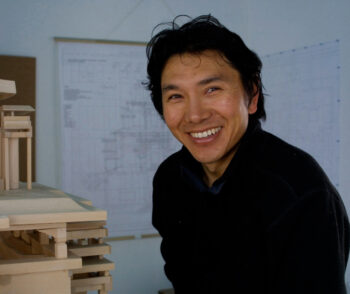

Pema Namdol Thaye; © Padma Studios® 2021.

When I was younger I never had the chance of looking at many old paintings from the masters. Now because of the internet and museum collections worldwide, one can see so much more. But in regard to 3D mandalas, there’s not so much that you can actually look at—3D mandala images are rare to find. I think one powerful thing is because I didn’t have those images when I was a young artist I had to look deeper to study the texts and the meaning and try to get the answer from the source, from blessings from the deity or the guru. I’ve had so many dreams of mandalas. Even now I’m using my dream source to make some of my design pattern on the mandalas.

Using western architectural tools that I learned at the Prince of Wales Institute of Architecture has made it easier to translate 3D mandala designs into modern blueprints. This helps the building process in terms of speed and accuracy. Initially though, I learned to draw blueprints by hand with a pencil. Now I create all the blueprints on a computer with AutoCAD. It’s so precise, down to a hairline, so there is no limit to how much detail I can create. Historically, in the tradition of Tibetan art, it is a big shift. In a way I think it tells a story. Didn’t Buddha say that the expression of dharma will change with time? I’m not changing the essence or celestial dimensions of 3D mandalas, because these are sacred, timeless, spiritual abodes, but I am changing how I make them by using modern tools.

Zangdok Palri Mandala by Pema Namdol Thaye; © Padma Studios® 2021.

In essence, tigtse are celestial measurements of any particular deity, its retinue, and mandala. These celestial measurements are bigger units that break down to smaller units—proportions. If it’s a Kalachakra mandala, then the measurements come from the Kalachakra Tantra, which is a teaching of the Buddha. If it’s a Zangdok Palri mandala, then it comes from Padmasambhava.

I find it quite challenging making the entrances and then joining them to the main internal structure. I find that the entrance is a mandala on its own, because so much detail goes into it. The other challenging part is that sometimes you have to visualize that you’re inside the mandala. You’re looking out. And when you look out, what do you see? For instance, in the text, it says you gaze through the skylight of the sun and moon. Now where is that? You have to find that. That’s not for me to translate. It’s celestial. Only the deities would know that.

Viewing blueprints at Padma Studios with HH Dudjom Rinpoche; © Padma Studios® 2021.

There are types of mandalas that describe the underground. It’s almost like a fort built underground. In Zangdok Palri, for example, the base structure is rooted in the naga world, in the water world. These base pillars are held by the great nagas (mermaids).

My goals are vast. I find that more than anything else showing 3D mandalas helps explain to people the deity phenomena and the spiritual world. People have seen thangka paintings, statues, and religious artifacts. But they haven’t seen 3D mandalas. Everyone who sees a 3D mandala gets tapped into it. Deities don’t need to live anywhere. It is we who haven’t unlocked that secret. Deities display 3D mandalas to unfold the secret in human beings. There is so much to study in the mandala, so much to look at. When people study more and more, they find the true answer of what or who they are.

Also in the text it says thongdrol—it means liberation through seeing. As soon as you see the mandala, you get liberated. That’s how powerful it is. Then when people see the mandala they say, “How come I’m not liberated?” I tell them that you are liberated. You don’t know because of your intense karma. You don’t see the effect, but the seed has already been planted. You’ve been blessed, and it’s going to unfold in the years to come. It’s the seed of liberation.

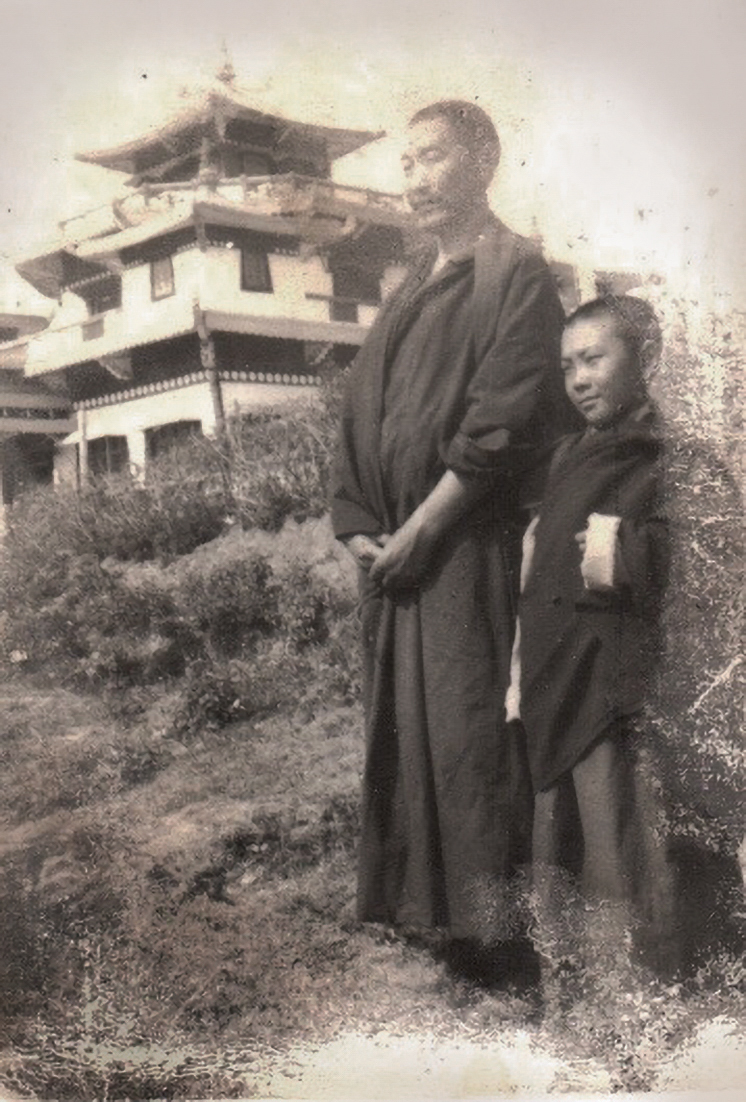

Pema as a child with his teacher in front of Zangdok Palri Temple, India; © Padma Studios® 2021.

I’m working on creating two life-size mandalas. One is in Nepal, which is a Zangdok Palri mandala temple. I was invited to design and build that by His Holiness Dudjom Rinpoche Sangye Pema Shepa. The previous Dudjom Rinpoche’s main mission was to build Zangdok Palri, and he built one in India when he fled from Tibet. The person who helped build and design that temple was my uncle, Lama Gonpo. So I learned from my teacher, and now I’m building the present one. I was also raised a few meters from that Zangdok Palri in India. As a child, I saw that structure built from the foundation to the top. It’s karma, as I previously mentioned.

The other mandala temple that I’m working on is a Zhitro mandala temple in Sikkim, India, for His Eminence Rigzin Dorjee Rinpoche. Inside will be the hundred buddhas, the bardo deities, from The Tibetan Book of the Dead. The idea is that you can walk inside the main mandala and look at each life-size deity. Same thing with Zangdok Palri—you can walk inside and see all the deities. It’s never been done before. You will experience the distinct vibration of the mandala as a whole, almost as if you are inside the womb of the deity.

Awakening for me is awakening from all the poisons. In Buddhism we have the three main poisons: ignorance, desire, and hatred. You can understand it, but to really know it and experience it is a totally different ballgame. Intellectually we know, but we have to take that dualistic knowledge to the wisdom level. Then when hatred is actually happening, wisdom steps in. But it’s hard. It’s a lifelong practice. We have to transform a little at a time by using all kinds of tools. For example, compassion. You become part of the phenomenon. Who can touch phenomenon? No one. Nothing but deeper awakening. You can’t teach that. You can’t buy that. That’s what awakening is for me.

Pema Namdol Thaye is a painter, sculptor, 3D-mandala specialist, traditional Tibetan architect, author, and art educator. An artist of Tibetan-Bhutanese heritage who studied in Kalimpong, India, he has won international acclaim as a master of traditional Himalayan arts. He was awarded permanent residency in the United States in 2008. In the same year he founded Padma Studios in Los Angeles.

Elena Pakhoutova is senior curator, Himalayan art, at the Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art and holds a PhD in Asian art history from the University of Virginia. She has curated several exhibitions at the Rubin, including Death Is Not the End (2023), The Power of Intention: Reinventing the (Prayer) Wheel (2019), and The Second Buddha: Master of Time (2018). More →

Get the latest news and stories from the Rubin, plus occasional information on how to support our work.