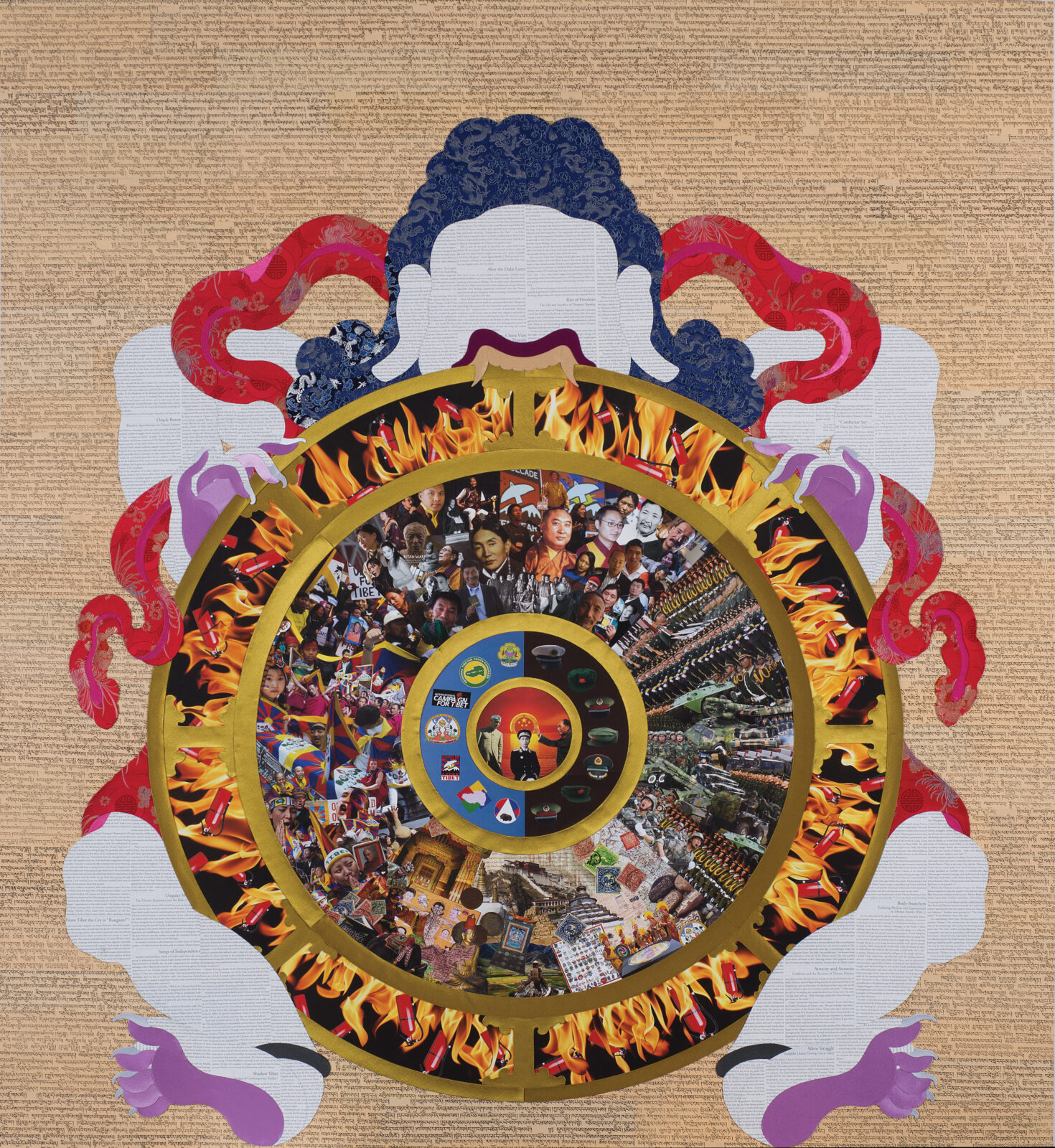

Artwork by Tenzing Rigdol

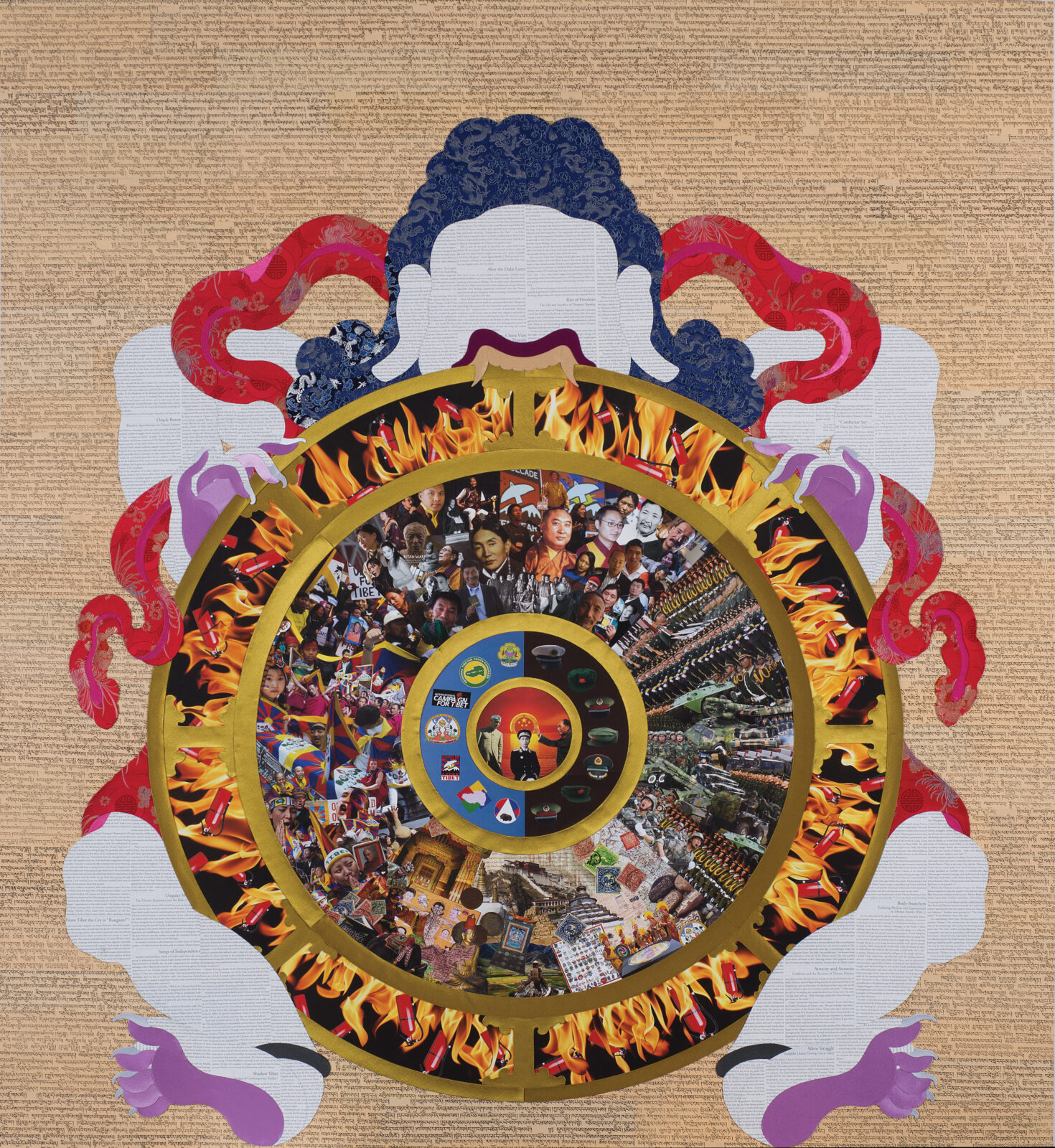

Artwork by Tenzing Rigdol

All of us are accustomed to living in our body, having been on this earth now for some time, so when death comes and we leave this body, we will face a big transition. In Tibetan the word for body is lu, which literally means “what’s left behind.” What we do not leave behind is our consciousness, which travels onward through the bardo—the intermediate state—to a new life.

The actions and deeds of our life heavily influence how our consciousness experiences this transition and where it travels to next. These actions have shaped our mind, and this shaping process is known in the Buddhist and Hindu traditions as karma. Karma is the momentum or energy that propels us through the bardo to find a new birth.

The bardo has two phases. In the first, your consciousness struggles to understand what has happened, slowly coming to realize that you have left your body and died. In the bardo, your mind occupies a mental body, but you may not yet have come to grips with that fact. Initially, you feel the same as you did while on this earth, and to prove that to yourself, you undertake activities such as jumping off a cliff or stepping into a fire. In this world, jumping off a cliff would lead to pain and broken bones, while stepping into a fire would cause serious burns. In the bardo, after you jump you discover your bones don’t break. When you step into a fire, you do not burn. This confirms that you have died and are in the intermediate state. Tremendous grief arises, especially if due to strong attachments in your previous life, you didn’t spend time contemplating and accepting impermanence and death.

With no physical body to limit your consciousness in the bardo, it is said that you can read the minds of others and perceive their emotional states. You can tell if they are experiencing well-being or pain, if they are feeling love and care for you, or if they have fallen into their own self-absorption. When you see their pain and loss, you draw close to your relatives and attempt to comfort them by saying, “Do not grieve, I am here.” But they cannot hear or see you, which provokes more of your own grief. When you observe the love and care your relatives once had for you fade, you feel immensely alienated and alone.

Sometimes conflict arises among your children or relatives over the little bit of money you earned with your own blood, sweat, and tears. To witness their disagreement causes you much pain and sadness. These leftover experiences of the previous life constitute the first half of the forty-nine days of the bardo.

In the second half, flashes of where you will be born in your next life begin to occur. This world will be unfamiliar to you. Nevertheless, as these flashes become more frequent, you gravitate toward them. In the bardo, the mind is flighty and unstable, darting around with great speed in a state of groundlessness. These flashes therefore appear to you as a refuge and a ground. From a deep impulse to find a home, you begin to turn toward your next birth as that home.

Depending on your karma, you are drawn to one of six realms. If it’s the human realm, you see your future mother and father making love, and as the egg and sperm come together, you look for an entry point. The teachings say that if you are to be born as a boy, there will be some aggression toward the father and attachment toward the mother. For a girl, it is the opposite; there will be aggression toward the mother and attachment toward the father. This attachment and aggression are part of what propels you to enter into your mother’s womb.

I believe that these tendencies in the bardo may account for why a father and son can have a challenging relationship, as can a mother and daughter. That point is not stated in the teachings explicitly, yet I imagine these dynamics may start before conception and influence the biological gender of the child. When we enter the mother’s womb, the mind forms in some fundamental ways, so it is traditional in Tibet to begin counting one’s age at the point of conception rather than birth.

You may be reborn in the animal, hungry ghost, or hell realms. To the degree that you have accumulated negative karma by living a life in which you have harmed other beings, you will find yourself in one of these “lower” realms. If your life consisted of working to be of benefit to other living beings, you will be born in the “higher” realms of humans, demi-gods, or gods. In this sense, our karma more or less automatically determines where we take our next birth.

If you are a practitioner and have spent your life meditating, then you have familiarized yourself with your space-like nature. At the time of the dissolution of this body and its elements, you will meet with a great opportunity to become fully awakened by recognizing the primordial ground, the nature of mind. With this deep stability in your mind and based upon your bodhicitta—the unconditional love and care you have developed toward all living beings—combined with a pure altruistic motivation, you can then choose to be born again to live a life of service to others and be of benefit to the world.

Dzigar Kongtrul Rinpoche was recognized by his root guru, Kyabje Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche, and the Sixteenth Gyalwa Karmapa as a reincarnation of Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Thaye. Rinpoche’s father was the third incarnation of tertōn Chokgyur Lingpa, while his first teacher, his mother, Tsewang Paldon, was a renowned practitioner, completing thirteen years of retreat. In 1989 Rinpoche moved to the West and began a five-year tenure at Naropa University as the first holder of the World Wisdom Chair. During that time Rinpoche founded Mangala Shri Bhuti, an organization dedicated to establishing a genuine sangha of the Longchen Nyingtik lineage in the West.

Get the latest news and stories from the Rubin, plus occasional information on how to support our work.