Illustration by Dan Savage

Illustration by Dan Savage

Are video games about power? It’s a common association, one well represented in Steven Spielberg’s movie—Ready Player One (2018), which portrays a virtual reality video game world called—OASIS. While the film mostly avoids explaining the game’s mechanics, it implies that players have worked hard to achieve their power within OASIS and the time and effort they’ve invested can be lost with the “death” of their character. For the protagonist, Wade Watts, the goal is fundamentally about power—win the contest and earn not only the prize money but also control over OASIS itself.

Of course not all video games are about the accumulation of power. Classic games such as Tetris or Mario Bros. don’t offer character progression, nor do more recent games like Telltale’s Walking Dead series or Blizzard’s Overwatch. These games are about making choices and mastering the game’s mechanics.

But the acquisition of ever-greater power is at the core of the identity and purpose of the games like World of Warcraft, Diablo, Skyrim, and Final Fantasy. They offer persistent characters whose progress is not lost when the player signs off: time invested in the game is accumulated and rewarded.

I am currently a game designer for Destiny, which is a perfect example. The quest for higher levels and greater numbers—which translate as power—is the driving purpose behind nearly all the game’s pursuits.

Game designers build power progression into video games because it is incredibly effective at hooking the player. We know there is an undeniable satisfaction in seeing phrases like “YOU ARE NOW AT LEVEL 2” appear on your screen. It exploits the brain’s dopamine reward system: the game asks the player to perform a series of actions and then rewards them with positive sensory feedback, in turn eliciting a dopamine response. This system is so effective that some people have accused popular games of fostering a kind of chemical dependency in their players.

This leveraging of the brain’s reward system has also led to a cynical comparison between video games and a Skinner box: an enclosed apparatus used to study animal behavior. Players take on the role of the lab rat, repeatedly pressing a button to generate a reward. I think this is an unfair comparison, as no behavioral scientist has ever sought to enrich the internal life of a lab rat. The pursuit of power in games affords an incredible variety of experiences beyond the reward response—enjoying a story, mastering a challenge, making a friend, or participating in a community, just to name a few.

But what is power in a video game? Typically it takes one of two forms. The first is an object external to the player’s character, for example a magic sword or a piece of the Triforce. The second is an intrinsic quality of the player’s character, represented with concepts like levels or stats like strength or intelligence. These representations of power are meaningful because they allow the player to overcome progressively greater obstacles.

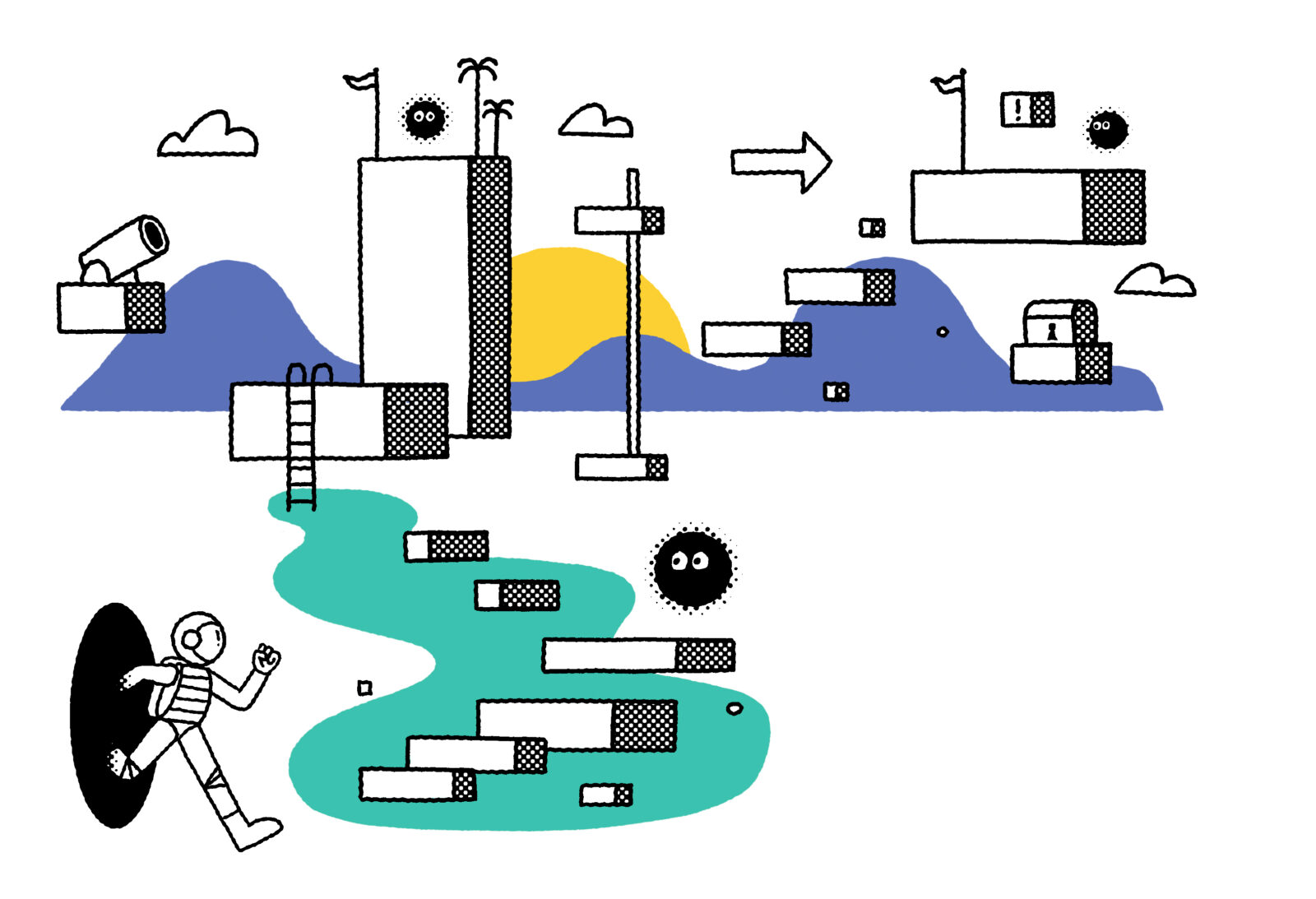

Game designers have a unique, strange relationship with power. We are responsible for creating both the obstacle and the means to overcome it. Our job is to establish an emotionally satisfying friction to the player’s inevitable progress. A common expression of this idea is the model in which the player overcomes an obstacle and is rewarded with the means to overcome the next obstacle. So players slay goblins until they attain a sufficient level to slay giants; then they slay giants until they attain a sufficient level to slay dragons; and on and on.

The cyclical form of this structure is not lost on players, who often describe it as a kind of treadmill or hamster wheel. The term “grinding” emerged with the rise of massively multiplayer online role-playing games (MMORPG), such as Ultima Online, Everquest, Dark Age of Camelot, and World of Warcraft. It refers to repetitive activity intended to increase one’s power. These games are notorious for demanding hundreds of hours to reach the pinnacle levels.

It’s a flippant analogy, but I think of grinding as a kind of asceticism. Players frequently compare stories about the hardships of their “grind” as a metric of their dedication to the game and an expression of the power they have achieved within it. Buddhist and Hindu traditions have examples of ascetics engaging in severe meditative practices to develop their tapas—a Sanskrit term meaning “heat” or “inner fire—”for the express purpose of growing in power.

Games like _World of Warcraft _or Destiny must sustain this progression over literally thousands of hours of play time. They are designed to function as self-contained hobbies, offering a persistent virtual fantasy world in which to explore your internal life. But this persistence has a side effect. If each obstacle the player overcomes provides the means to overcome the next obstacle—and there is no end of obstacles—what is the point? Isn’t it akin to the myth of Sisyphus? To borrow words from the French philosopher Albert Camus, is the struggle itself toward the heights enough to fill a man’s heart?

When I consider these questions, I often think about the game Progress Quest, first released in 2002. It was a text-based role-playing game in the vein of Dungeons & Dragons that sat in the corner of your monitor while you did other activities on your computer. Beyond creating a character, the player did not have to interact with the game at all. It simply played itself. A ticker spewed out text describing the character’s actions as they went about their business of slaying monsters and acquiring treasures. The game is satirical. It pokes fun at our obsession with the acquisition of power and wealth, which take precedence over substantive adventure and heroism.

Progress Quest was absurd, but it was also a remarkably compelling game. And while it was comedic, it was also prophetic. The many “clicker” and “idle”—collectively referred to as “incremental”—games like Idle Heroes, Clicker Heroes, and Tap Titans that currently populate the iTunes and Android stores are essentially iterations on the Progress Quest model. What once was satire has become a genre in its own right.

Illustration by Dan Savage

Today in China many of the top mobile games fall into the role-playing game (RPG) genre. They often feature auto-play modes, so the specific tasks of adventuring are automated. Left alone, your character will wander about the world, fight monsters, collect treasures, and level up. Players need only concern themselves with macro-level decisions in their character’s power progression. The game designers have abstracted the grind, allowing the player to slide into the observer seat at will.

It’s tempting to view these games with condescension, as a game that plays itself can’t be considered much of a game, right? But I think this perspective is misguided and passes over the reason behind the popularity of auto-play games. Rather than missing the point, auto-play games might actually reveal the point: humans derive an intrinsic satisfaction from observing progress.

Power progression in video games is a means of quantifying a need and representing that need visually. We feel satisfaction when we observe that need fulfilled. Our participation is no more a requirement for that satisfaction than the requirement that we actually hold the sword of ultimately slaying. It’s enough to see your character wield it.

Power is progress, and progress is satisfying. Work is getting done. Things are getting better.

Gavin Irby is a lead designer at Bungie, Inc., where he works on the Destiny franchise. He has spent his career helping build online game worlds that support thousands of simultaneous players, including Rift: Planes of Telara, Wildstar, and Pirates of the Burning Sea. Prior to entering the games industry, Gavin attended the University of Virginia as a graduate student in the History of Religions Department, where he specialized in Sri Lankan Buddhism and Hinduism.

Get the latest news and stories from the Rubin, plus occasional information on how to support our work.