Nicholas Christakis:

My interest in social networks actually began with a prior interest in the widowhood effect, which is the increased probability of the recently bereaved to die.

Devendra Banhart:

Professor Nicholas Christakis is a social scientist and physician who conducts research in the areas of social networks and biosocial science and directs the Human Nature Lab at Yale University.

Nicholas Christakis:

I’d been caring for people who were dying. They would die, and then within a few months, their spouse would die of a broken heart. So there was an old literature on dying of a broken heart. And I started doing research on this topic, studying why is it that when your partner dies, you are more likely to die? And that is actually one of the most powerful illustrations of the role of interdependence and health, because death is a serious health outcome, and marriage is a serious illustration of interdependence. And here we have the two of them connected when people die of a broken heart.

Devendra Banhart:

Welcome to season 5 of AWAKEN, a podcast from the Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art about the dynamic path to enlightenment and what it means to “wake up.”

I am Devendra Banhart, singer, songwriter, artist, and your host. In this season, we hear from experts in the realms of art, social science, Buddhism, and more to better understand how interdependence is the foundation of every aspect of our lives.

Himalayan art has long been a pathway to insights and awakening, and over the course of eight episodes we look specifically at a painting of the Wheel of Life to see what it can teach us about the interconnected nature of existence.

Throughout this journey, we’ll discover how greater awareness of our interdependence can be the wake up call that motivates us to take actions for a better world.

In this episode: Health.

Our bodies may be the single most tangible reminder of the reality of interdependence. For them to function, every part and system at every moment has to work together in a wholly interconnected and fluid way. But, as Nicholas Christakis’s story reflects, good health isn’t limited to just physical functioning—there’s an emotional component as well. In fact, a core part of Tibetan medicine is the knowledge that our health is not only dependent on what we eat and drink but how we move and rest, how we feel, and the community around us.

Dr. Nida Chenagtsang is one of the world’s most renowned Tibetan doctors. He is the founder and medical director of the Sowa Rigpa Institute and Sorig Khang International, organizations dedicated to preserving and promoting traditional Tibetan medicine. Dr. Nida was born in the Amdo region of Tibet. He was not always inclined toward a career in medicine, but once he found his path, he never turned back.

Dr. Nida Chenagtsang:

I was born in a yurt in the nature, you know, it’s a very, very, very old, very, very old fashioned. Very, very old fashioned and very organic. So for me, remembering my homeland is the nature, the grassland. And I always felt like that’s it. I’m part of the nature and nature part of me, kind of the bond, interconnection was very, very powerful.

And, when I grew up in the grassland, I was connected with nature, but then start to go to school, and then the buildings, houses, houses, houses. I really felt something is missing, disconnected. And then one day I went back to my birthplace. My dad was there and I was barefoot. And, just walking, you know, and then near a little river and this, and suddenly like my barefoot touch on the flowers. These flowers, I think is the yellow buttercup flowers. And then I really felt like these flowers are talking to me. And I really felt like this feeling of acceptance, And a feeling of belongingness. And I really had a very, very, very deep, I don’t know, more spiritual or natural, very powerful experience. And then my tears are just coming, just, just like cry. It is not like a sad, but I really thought that’s it. I’m part of this nature and nature is part of me, and we are forever bonded. And then I really felt like this unimaginable beauty and harmony, between humans and nature. But, in that case, between myself and the flowers and the grassland, and the river and the mountain, all these things is completely like a union.

And then my tears are coming, and I was stuck there. That’s the power of nature. And that power of nature comes when we are connected. That’s why this interconnection is so important. It is not just I am a part of the nature, or we are part of the nature. And nature is part of us too, You see, it is not just a one way, it’s a both way.

And then one of my friends says, oh, there’s a Tibetan medicine class, and, one of our local doctors teaching in the evenings, you know, this is very kind of Tibetan style. The old doctors and evenings at their home, they give free lectures, you know, talking, anybody can go there. So I went to join one of this class.

And then one of other teachers says, oh this August, if you want to join us picking up herbs, we go to the herbal camp, we bring our tents and come there for a week and picnics and hiking and picking up herbs and studying and this. And then I hiked a mountain and went very, very, very up. And I just sitting, it’s kind of that time I don’t do meditation, you know? And I just sitting and relax.

I really felt that giant mountain, you know, is talking to me. And I knew that was my inner voice too. Again, like, you are me. You are me, and I’m you. Right? So all about the essence of our human existence is the nature. And like we are ever connected, there’s no separation. And then when I come to wake up from that feeling, I said, that’s it. Then I was 17 years old, that’s why I’m saying now I can make my own decision.

What I want is Tibetan medicine, because Tibetan medicine is herbs, it’s nature. It’s the fresh water, it’s the soil, you know, it’s about organic food. It’s the plant and it’s the talk. It’s the connection. And everything is interconnected.

Many people, when they think about health, they say, oh, I’m healthy, you know, physically. But health is much more than that. And our health is depending on our diet, our health is depending on our lifestyle. Our health is depending on our sleep quality, our health is depending on the environment, our health is depending on the society, social connections. And especially when we talk about holistic medicine. So what does it mean? You know, the holistic medicine is the expression about the interdependency and interconnectivity, and especially in our time today, that the nature of this, the power of the interdependent is so strong.

Devendra Banhart:

Dr. Nida went on to become a doctor and now trains aspiring doctors all over the world. He teaches the importance of balance and taking a broad view of what health means, including our social connections. Again, Nicholas Christakis.

Nicholas Christakis:

One day I was working on the South Side of Chicago, taking care of an older woman who was dying, who was being cared for by her daughter. And the daughter was exhausted for caring for for her mother, who was dying of dementia. And the daughter’s husband had become depressed because his wife was exhausted for caring for her mother. And the husband’s best friend was really worried about his friend. And I get a phone call one day from the daughter’s, husband’s best friend, calling me as the hospice doctor, taking care of this woman for help. I suddenly had this realization that this phenomenon I’ve been studying in my lab, the widowhood effect wasn’t restricted just to husbands and wives and wasn’t even just restricted to pairs of people. It could ripple through the network and affect other people. And that really opened my own eyes. I mean, health is very connected to our social interactions.

Dr. Nida Chenagtsang:

It’s just like a huge web, like billions of billions of little dots. They’re all, interconnected and interdependent. So we cannot talk about health without talking about the human relationship, you know, our social relationship, we can, we cannot talk about psychology. What’s something very important is we know that we humans are animals. And these animals, you know, have a very special characteristics. And the first one is intelligence. We are intelligence animals. And the second one is, we are super social animals. So what, what is a healthy structure of the social? And there’s a good inter-connection and interdependence.

I often say one of the most powerful Buddhist philosophy is interdependence. But we should not see as a philosophy, we should see as the foundation of essential power of human existence. It is like interdependent or interconnection is like a synergy. Because of this synergy. We have energy. Because of this synergy, we are still alive, right? So we can be happy, you know, we can be productive, and we can be functional, and we can help others.

Devendra Banhart:

This season we’re focusing on a painting of the Wheel of Life in the Rubin Museum’s collection. The Wheel of Life, also known as the Wheel of Existence, is a foundational symbol in Buddhism and offers a visual representation and reminder of the cycle of life, death, and rebirth. Part of the wheel depicts the six realms of existence where it is possible to be reborn. To see the artwork in detail, go to rubinmuseum.org/wheel.

Here, professor Annabella Pitkin who teaches Buddhism and East Asian religions at Lehigh University, talks us through the hell realm.

Annabella Pitkin:

In the Tibetan Himalayan artistic traditions, hell is always at the bottom. It’s the very, very worst realm. And very, very importantly, before we even describe for ourselves the nature of the sufferings that beings are undergoing there that are pictured in this image, we really have to remind ourselves again that this is a dynamic model of the universe, and that the processes through which living beings find themselves in a hellish state, just like the processes that cause living beings to find themselves in a God realm or a hungry ghost realm, or an animal realm, or a human realm, those processes are infinitely ongoing. They are dynamic. They are part of a universe that’s always changing, and so hell is the worst state of being they can find themselves in.

It’s so agonizing there. It’s very hard to remember that we could be free. However, this optimistic picture doesn’t just show us the terrors. It also shows us, once again, the Buddha standing up and teaching, and the Buddha has not forgotten the beings in hell. They are not abandoned, and they are in no way doomed forever. The Buddha is saying, even in the most hellish experience, we can remember our connection with one another, our real community with one another. And it is actually possible to generate loving kindness and compassion, even under situations of extreme pain. And that profound insight from the Buddhist traditions is more relevant than ever in the world we live in now, in which so many communities and tens of millions of people are suffering so extremely from war, from displacement and loss of home, from climate change, from disease and epidemics, and poverty, from so many forms of agonizing suffering.

And the image of the painting is suggesting that we are not trapped by those situations. We are the kinds of beings who are eminently capable of reconnecting at any point with the love and compassion and care that according to this image, and to Buddhist, is the path to freedom and to actual healing of the whole hellish situation.

The message that goes with it is this really profound message of transformation that says, the minute that one can cultivate in the midst of one’s own pain, love, or care, or even just a small wish for the person next to us to feel a little bit better, that wish sets us free. And the person next to us, the Buddha is said to have been in his sojourn in hell yoked to a cart next to another, suffering being, and the Buddha to be the Buddha during that sojourn in hell is said to have tried to take the load upon himself. And that small act of compassion was enough to break hell open and to set the Buddha free. So that possibility then is available to all of us. The moment we can return to this awareness of our own interdependence, the flames of hell fall away.

Devendra Banhart:

Reconnecting with our understanding of interdependence doesn’t just come through knowing we’re all connected, but also realizing that those connections can have lasting consequences for our health and well-being. Nicholas Christakis.

Nicholas Christakis:

Our friends don’t just transmit information and germs to us. Our friends also model good and bad behaviors. So if your friends are all smokers and you become a smoker, that’s an example of how, despite having friends, which is good for you, the fact that those friends are smokers and are making you a smoker is bad for you. So the way I think about this is connection and contagion. There’s the things that have to do with our connections to each other and things that have to do with the contagion across the connections that we make with each other. So our friends affect us in terms of our health habits and in terms of the knowledge that they bring. Or for example, you know, if, let’s say you get diabetes and one of your friends has diabetes, and your friend says, you know, I’ve had a long experience managing diabetes. Here’s how I manage it. Or here’s a good doctor to go to to help care for your diabetes. That’s a way a friend of yours could be helpful to you in a health type situation.

Dr. Nida Chenagtsang:

We’re interconnected. Actually, it’s interdependent. Our health, it’s very clear. Depends on what we eat, what we do. So that’s why Greek medicine says, we are what we eat, right? And Tibetan medicine says, our health is depending on what we eat and what we drink, it’s not only what we eat and what we drink. Our health is depending on what we do.

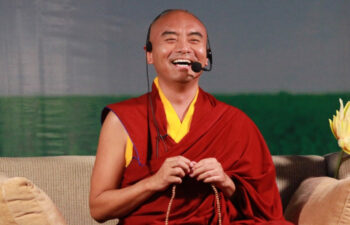

Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche:

There are four things that we need to think about. First is the food.

Devendra Banhart:

Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche is a renowned meditation teacher, author of several books on Buddhism, and head of the worldwide Tergar Meditation Community.

Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche:

So what kind of food we should eat. So normally we call the food, we talk about elements and then temperature. So a heat based food, cold based food, and then like neutral food, something like that. The detail, you have to look at them, each food. So like for example, it’s similar like modern, not too much oily, not too much protein, not too much, not very little protein, not too much carb. So it has to have balance, everything. So nowadays, sometime people say only protein or only cup or only vegetable. So sometime they say, what is the best food? So I said the best food is variety. It’s difficult to find only one best food. People nowadays they have this question. The one thing is the best. You know, we always look for singularity. This is very difficult to find the singularity. It’s interdependent, so many cause and condition. And so to find the food also have balance.

Dr. Nida Chenagtsang:

So that’s why you see, natural medical system is holistic and, the synergy, the energy is all about the interdependence. I always tell my patient, I try to help you, support you, but you are the healer. We need to have a different way of thinking.

Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche:

And then second is what we call balance between resting and acting. In the ancient time most people do movement. So there’s not worry too much about less movement because most of people are farmer or nomad, they have to clean.

Dr. Nida Chenagtsang:

They’re out, you know, on the grassland, all farmers there in the field, right? Everybody, like, and old society, you know, ancient time everybody very active outdoor. But today, we’re not active, you know, including the kids. So that’s how if somebody is physically active, doing exercises or sport or walk or whatever, regularly doing, actually, this is a sign of a healthy person.

Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche:

If you don’t move at all, then body become unbalanced and then it’s not good. But if you too much movement without resting, I think it may not be good. Resting and movement to find balance. And then, sleep is similar like six hours to eight hours, but too much sleep also no good, too much sleep. Then the organs lose function. Mind become very dull, like maybe overly more than eight hours sleep every day might be not so good, I’m not sure. But there’s not so much nowadays research about that.

Dr. Nida Chenagtsang:

I can say in a simple way that healthy person can get seven to eight hours of sleep. And that person has awareness, emotional awareness. So because of that awareness, you know, a good emotional manager, you understand some people says, oh, I’m a good emotional manager. My sleep is disaster. I doubt him that because emotions and sleep qualities, interconnected, interdependent. So that’s why for me, sleep quality is very important.

Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche:

If you think too much, concentrate too much, then energy go up. So this is why what we call the stress, stress is think too much, concentrate too much. Then mind become wild, lot of sensitive, like anxiety, depression, panic, all this comes special before go to sleep, don’t concentrate too much otherwise energy go up. The element in the body. So special, we have the meditation. So if the mind true active than what we call calm, abiding meditation. So shama meditation, if mine is too dull and not energy, then analyze analytical meditation, get more energy, and overall find this balance. So these four things are very important for the for the health and for the mental health, for the physical health and also for the spiritual practice.

Dr. Nida Chenagtsang:

I think the more we understand what natural medicine is, and the more this holistic health awareness, we must have, including the patient. We need to find the balance. And we have to wake up, okay, here, I’m bringing the Buddha’s message. Buddha means wake up. We really need to wake up, right? And most of the disease can be prevented. Number one, target is healthy people. Hey, healthy people wake up, right?

So many people are there, worried, anxious, anxiety. What happens the next day? What happens the next months? What happens in next year? What happens? You know, if I lose my job, what happens? This and that? I often say sometimes, don’t ask these questions. What happens to me? You should more think what happens to us. You’re not alone. We are interconnected, right? Interdependence, it means I’m not existing just by myself. You know, I’m here. My partner is, my kids are here, my friends are here, my parents are here, my this. And then, then we don’t need to worry too much.

There’s a Tibetan expression, I really like it. It means that somebody is not sick yet healthy people help them to maintain their good health. Keep your balance. That’s it. Balance.

Devendra Banhart:

Balance. It’s that simple. And remembering we’re always in relationship. We have to support, help, comfort, and celebrate one another, as our social connections are inextricably tied to our mutual well-being.

You just heard the voices of Dr. Nida Chenagtsang, Nicholas Christakis, Annabella Pitkin, and Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche.

I am Devendra Banhart, singer, songwriter, artist, and your host.

To see the artwork discussed in this episode, go to rubinmuseum.org/wheel.

If you’re enjoying the podcast, leave us a review wherever you listen to podcasts, and tell your friends. For more stories and news from the Rubin, follow us on Instagram @rubinmuseum and sign up for our newsletter at rubinmuseum.org.

AWAKEN season 5 is an eight-part series from the Rubin.

AWAKEN is produced by the Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art with Kimon Keramidas, Gracie Marotta, Christina Watson, and Sarah Zabrodski in collaboration with SOUND MADE PUBLIC including Tania Ketenjian, Philip Wood, Alessandro Santoro, and Aaron Siegel.

Original music has been produced by Hannis Brown with additional music from Blue Dot Sessions.

AWAKEN Season 5 is sponsored by The Prospect Hill Foundation and by generous contributions from the Rubin’s Board of Trustees, individual donors, and Friends of the Rubin.

This program is supported, in part, by public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, in partnership with the City Council.

Thank you for listening.

Our bodies may be the single most tangible reminder of interdependence. But good health isn’t just related to physical functioning—there are emotional and social components as well. What can a holistic perspective on health offer us? And how do our relationships relate to our well-being?

For centuries people have turned to the image of the Wheel of Life to better understand cause and effect and the very nature of existence. The section of the Wheel depicting the hell realm is the focus of this episode’s exploration of health.

This episode features Tibetan physician, scholar, and founder and medical director of the Sowa Rigpa Institute Dr. Nida Chenagtsang. AWAKEN season 5 is hosted by singer, songwriter, and artist Devendra Banhart. Other guests in this episode include social scientist, physician, and professor Nicholas Christakis, professor of Buddhism and East Asian religions Annabella Pitkin, and Tibetan Buddhist meditation teacher and author Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche.

Wheel of Life, attributed to Lhadripa Rinzing Chungyalpa (b.1912, Sikkim–d.1977); Sikkim; c. 1930; pigments on cloth; Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art; C2004.21.1

One of the most important teaching tools in Tibetan Buddhism is the Wheel of Life, also known as the Wheel of Existence, which demonstrates the cyclical nature of life, death, and rebirth. The scenes within the wheel portray the laws of karmic cause and effect, illustrating how a person’s actions bring about positive or negative outcomes in their current and future lives.

The most frightening scene in the Wheel of Life is the hell realm, which depicts tortures such as cutting, boiling, and freezing. This realm is a frightening place filled with fire, red-hot pokers, and monsters eating faces. The wrathful deity surrounded by flames near the top is Yama, who presides over the hell realm, while the presence of the standing blue buddha figure indicates that even in hell there may be some interventions from awakened beings. Along with the hungry ghost realm, the hell realm seems fantastical in its awfulness, but the suffering is echoed in real-world problems, such as war, climate change, disease, and poverty.

Devendra Banhart is an internationally renowned musician considered a pioneer of the “freak folk” and “New Weird America” movements. Banhart has toured, performed, and collaborated with Vashti Bunyan, Yoko Ono, Os Mutantes, the Swans, ANOHNI, Caetano Veloso, and Beck, among others. His musical work exists symbiotically alongside his pursuits in the other fine arts including painting, poetry, and drawing. The Venezuelan American has released 11 albums. His drawings and paintings have appeared in galleries all over the world, including the Art Basel Contemporary Art Fair in Miami; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; Palais des Beaux-Arts in Brussels; Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles; Nicodim Gallery; and Serralves.

Dr. Nida Chenagtsang is a renowned Tibetan physician, scholar, and lineage holder of the Yuthok Nyingthig, the unique spiritual tradition within Tibetan medicine. Born in Amdo, Tibet, he began his medical training at the local hospital before earning his degree from Lhasa Tibetan Medical University in 1996. Alongside his medical studies, Dr. Nida immersed himself in Vajrayana Buddhism, receiving training from esteemed masters across all Tibetan Buddhist schools, with a focus on the Longchen Nyingthig, Dudjom Tersar, and Yuthok Nyingthig traditions. A well-known poet in his youth, he has published books and articles on Sowa Rigpa and Yuthok Nyingthig, as well as groundbreaking research on ancient Tibetan healing practices. As the founder and medical director of the Sowa Rigpa Institute, Dr. Nida continues to share the wisdom of Tibetan medicine worldwide.

Nicholas A. Christakis, MD, PhD, MPH, is the Sterling Professor of Social and Natural Science at Yale University. His work is in the fields of network science and biosocial science. He directs the Human Nature Lab and is the co-director of the Yale Institute for Network Science. He was elected to the National Academy of Medicine in 2006; the American Association for the Advancement of Science in 2010; the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2017; and the National Academy of Sciences in 2024.

Annabella Pitkin is associate professor of Buddhism and East Asian religions at Lehigh University. Her research focuses on Tibetan Buddhist modernity, Buddhist ideals of renunciation, miracle narratives, and Buddhist biographies. She received her BA from Harvard University and PhD in religion from Columbia University. She is the author of Renunciation and Longing: The Life of a Twentieth-Century Himalayan Buddhist Saint, which explores themes of non-attachment and teacher-student relationship in the life of Khunu Lama Tenzin Gyaltsen. More →

Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche is a recognized tulku of the Kagyu and Nyingma lineages of Tibetan Buddhism, a teacher, spiritual leader, and bestselling author. He possesses the rare ability to present the ancient wisdom of Tibet in a fresh, engaging manner. His profound yet accessible teachings and playful sense of humor have endeared him to students around the world. Rinpoche’s teachings weave together his own personal experiences with modern scientific research in relation to the practice of meditation. He has authored several books including two bestsellers: The Joy of Living: Unlocking the Secret and Science of Happiness, which has been translated into over 20 languages, and In Love with the World: A Monk’s Journey Through the Bardos of Living and Dying. His recent TED Talk is titled “How to Tap into Your Awareness—and Why Meditation Is Easier Than You Think.” Rinpoche teaches extensively around the world and oversees dharma centers, including three monasteries in Nepal, India, and Tibet, and the Tergar Institute in Kathmandu; Tergar meditation communities on six continents; numerous schools in Nepal; and social engagement projects related to health, hunger, hygiene, the environment, and women’s empowerment issues in the Himalayas.

Get the latest news and stories from the Rubin, plus occasional information on how to support our work.