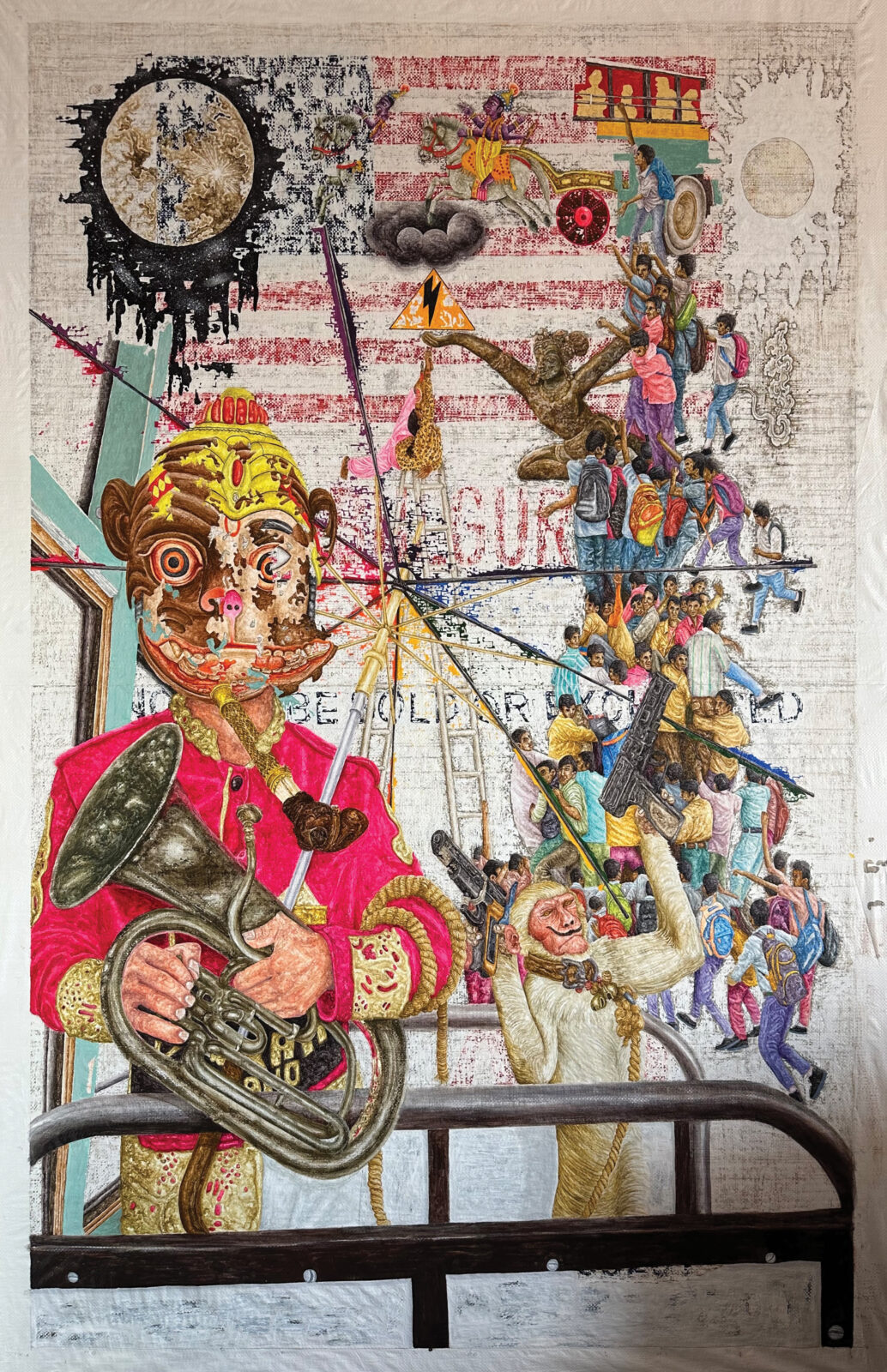

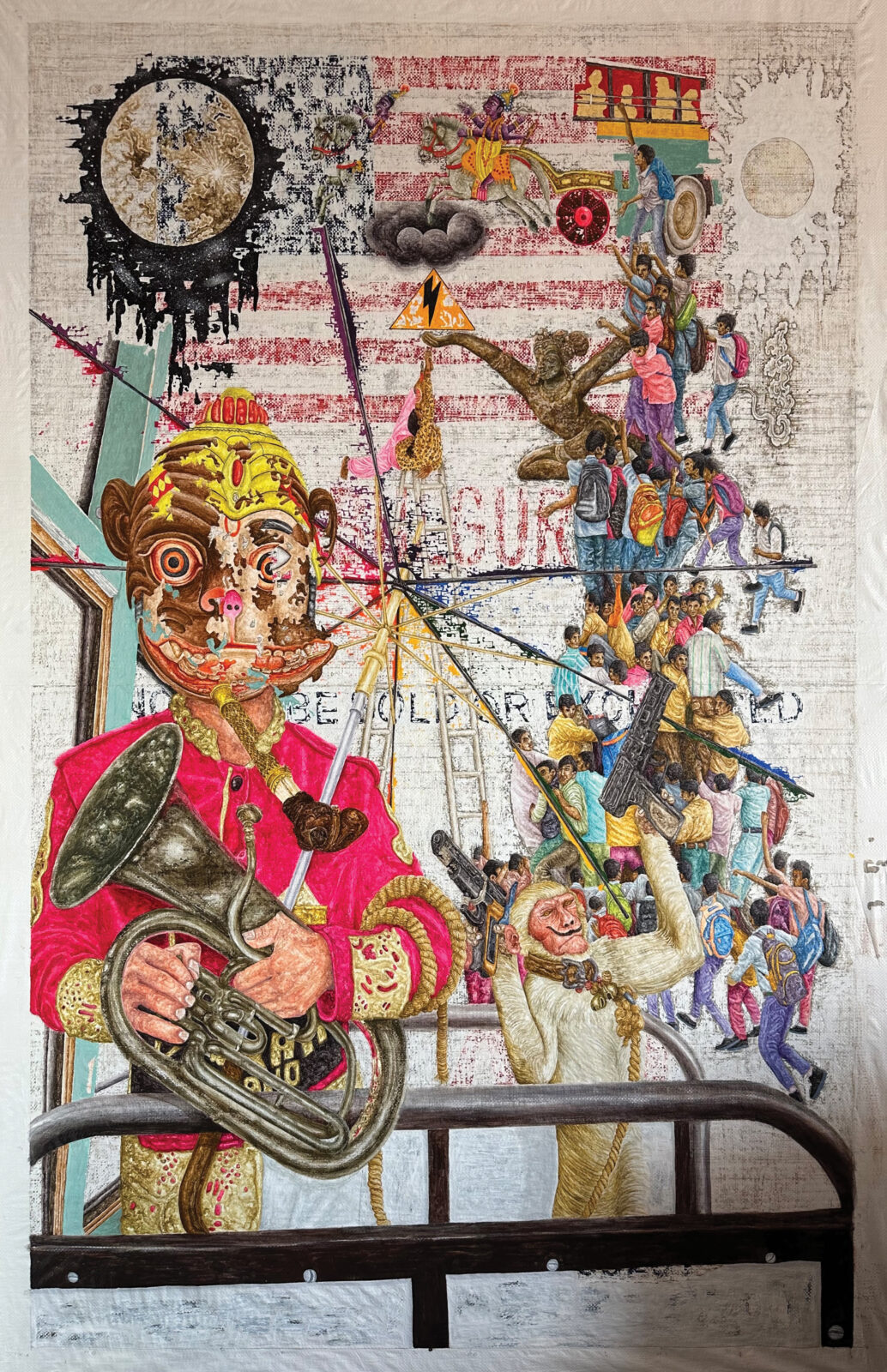

Tenzin Gyurmey Dorjee; chants of a monkey mind; 2023; acrylic on tarp; Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art; C2024.1.1

Tenzin Gyurmey Dorjee; chants of a monkey mind; 2023; acrylic on tarp; Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art; C2024.1.1

Reimagine: Himalayan Art Now presents artworks by thirty-two contemporary artists, many from the Himalayan region and diaspora, juxtaposed with objects from the Rubin Museum’s collection. Co-curator Tsewang Lhamo interviewed artist Tenzin Gyurmey Dorjee about his process creating a new work for this exhibition.

Tenzin Gyurmey Dorjee: My works are important to me because of their subjects. Most of the time, I choose my family, my friends, and people I deal with on a daily basis as the main subjects.

For this show, I chose the local bus stand in New Delhi because I’ve been using that space for a very long time. This bus stand has become kind of my family in a way. So the characters in the painting, along with the materials, all come from my experience being on the bus.

There are lots of people here in this artwork, and it reflects the fact that India is the most populated country in the world. Delhi is one of the most dense cities in India. When I go to the bus station in the morning, which is the busiest time of day, people do not fit in the bus. So in the painting, there are characters that come out from the bus, sort of like a tower going up in the sky.

Some of the characters shown are Indian circus performers, musicians in bands who play instruments during marriage seasons, and sex workers, who are commonly seen at bus stations in India.

What this particular work means to me is that despite having your own country, culture, and religion, without understanding each other on a humanity level, I think we all are lonely and narrow-minded. Our differences shouldn’t act like a cage.

I normally paint with acrylic on a tarp. We call it drochak bureh (drochak means barley and bureh means sack). This material is important for me because when we were kids you could see these bags everywhere in our towns on broken windows to cover them, during construction, as garbage cans, and some people even made bath loofahs out of them. During college, canvas was so expensive for me, so I began to use this material.

I see it as a symbol of our refugee situation. My parents would say, “We are refugees. That’s why we are getting this.” The bags were filled with food supplies as aid, and they were given by the United States to Tibetan refugees back then. The ones you see now are quite different from the ones from back then, especially the ones in Delhi. But they also carry its role in a different way, used for different things.

I’m playing with three objects from the collection: the Monkey Mask, the Kang Ling leg bone trumpet, and the Garland Bearing Apsara wooden carving that the Rubin recently returned to Nepal. I saw it in the newspaper and thought it was very brave of the Rubin Museum to give it back to Nepal, so you can see its return in my work as well.

I use the Monkey Mask for my character because of Hanuman, who is very loyal to Ram. I want to show my loyalty to the Indian community, like Hanuman does to Ram. Indians are very kind to us. On top of that I use the Tibetan mask, which represents me. With the Kang Ling trumpet, it is a juxtaposition with the Indian band Baja instruments. The Kang Ling reminds us of emptiness and impermanence, and the band Baja is kind of materialistic and represents attachment, because it’s usually present in marriage ceremonies in India.

Monkey Mask; Bhutan; c. 19th century; Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art, Gift of Bruce Miller and Jane Casey; C2016.1

Leg Bone Trumpet (Kang Ling); Tibet; 18th-19th century; Human bone, copper, coral, leather; Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art, Gift of Robert and Lois Bayils; SC2019.3.2

I normally stop and try to find humor in my work, and then I call my friends and talk about it. It somehow changes the way I see my work when I joke about it with my friends. From there, I am able to create new paths. Even my father says, when you are going through great misery or you are stuck somewhere, you should realize that there’s always humor in it. I hope my paintings can bring humor into peoples’ lives. Making a full painting and letting it go by selling it and then making another one—that is part of the process for me.

Love. Without love there is no joy as a being. It makes you lonely. That’s the special thing about humans. We can love each other without any kind of boundaries about our culture and everything else.

Because of technology, I can see what other artists are doing and what galleries are showing new works. It helps a lot when seeking inspiration. Because we are able to communicate so easily now due to technology, it will be better for our art community, and art can better technology and community too.

When I was in school, I never liked to collaborate with people. I found it a disturbance when I needed personal space. I think in other places, even when you collaborate, there is still some personal space. But in India we don’t have any personal space.

Someday in the future, I want to collaborate with my senior artists. That inspiration came from Andy Warhol and Jean Michel Basquiat when they collaborated.

These artworks were featured in the exhibition Reimagine: Himalayan Art Now, on view at the Rubin Museum from March 15 to October 6, 2024.

Tenzin Gyurmey Dorjee was born in 1987 in Kamrao Village, Himachal Pradesh, India. He is interested in exploring the paradoxes present in ordinary things and how global changes in culture, politics, climate, and science can impact local surroundings. His father, Tulku Troegyal, taught him drawing in the Tibetan traditional style at the age of six, and he has been practicing arts professionally since 2013. His studio practice is currently based in Delhi.

Tsewang Lhamo, also known as Tselha (they/ཁོང་), is a queer Tibetan multidisciplinary artist, self-taught filmmaker, and cultural producer based in Queens, New York. Born in Nepal, they grew up in a Tibetan refugee settlement in South India. Previously a graphic/web designer, they founded the Yakpo Collective, a Tibetan contemporary art platform centering Tibetan creatives around the world. They are also one of the organizing members of Tibetan Equality Project, a space dedicated to the queer Tibetan community in diaspora. In the future, they plan to create feature-length queer Tibetan films.

Get the latest news and stories from the Rubin, plus occasional information on how to support our work.