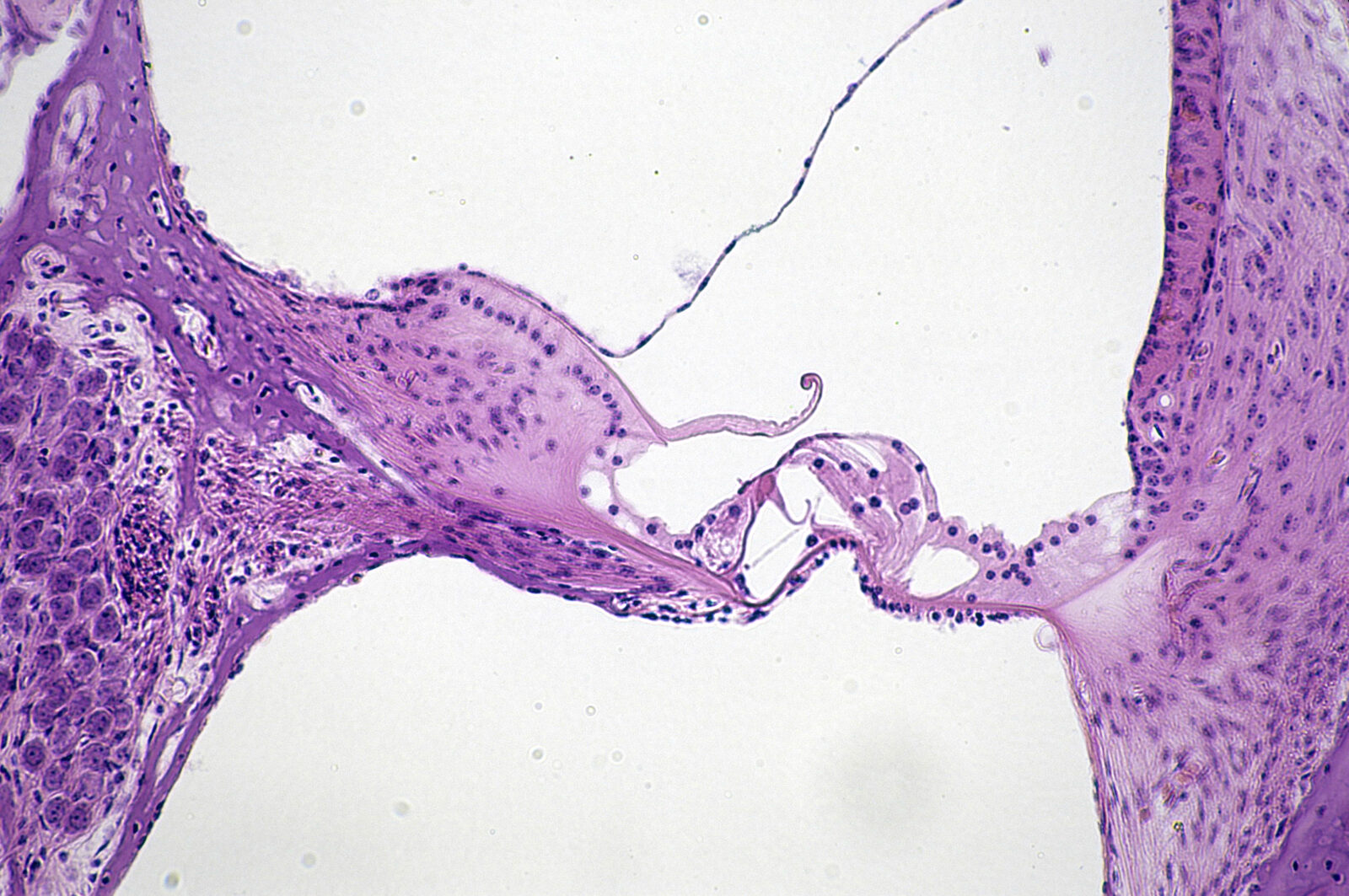

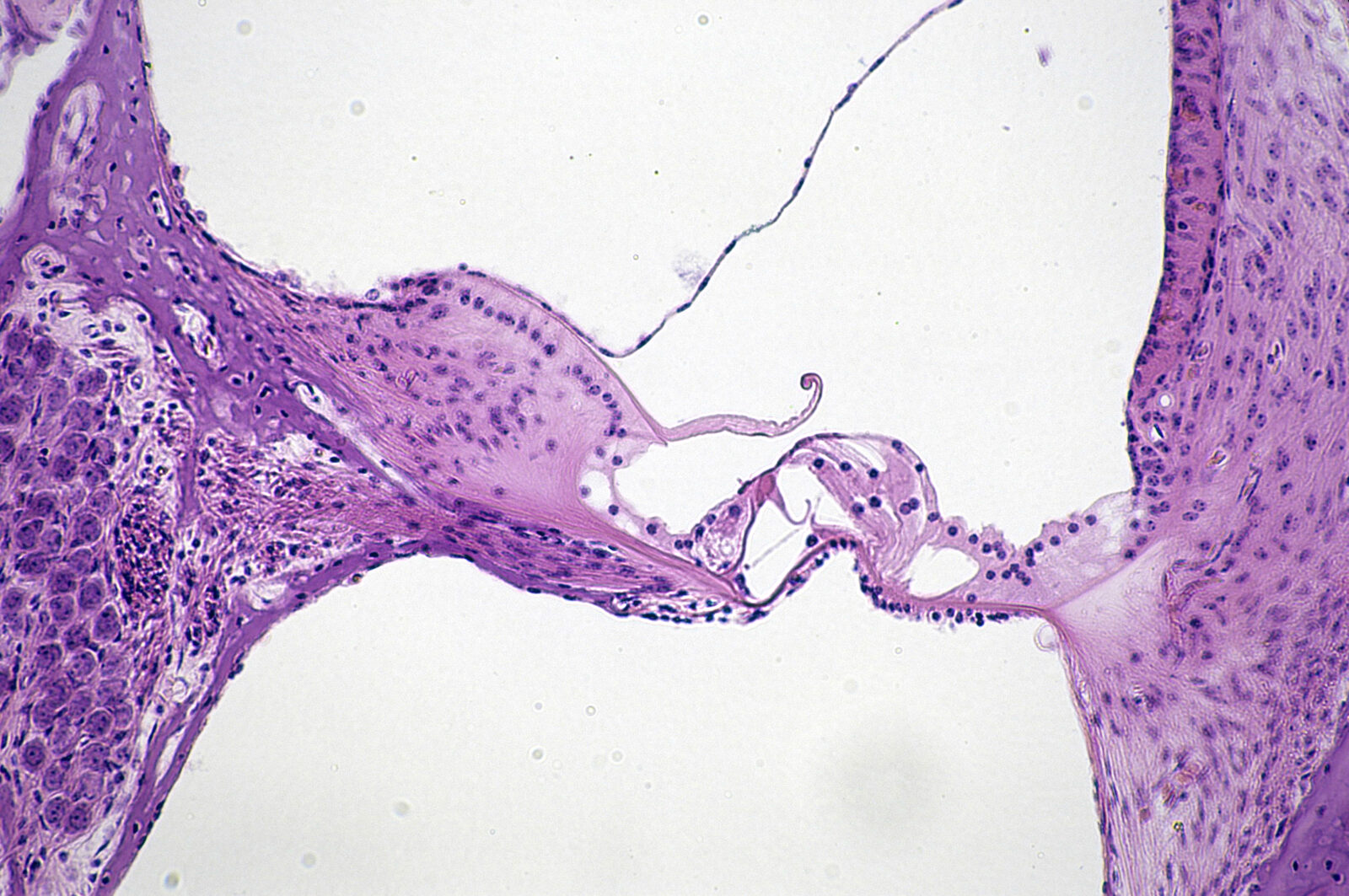

Inner ear (25X magnification). © Ed Reschke/Getty.

Inner ear (25X magnification). © Ed Reschke/Getty.

We’re certainly hardwired for sound. The research seems to suggest that we’re also hardwired for music in particular. It’s not for just one reason but a host of evolutionary forces. One of those is the communicative nature of music. Music is an exaggerated signal in terms of speech, exaggerated in its contours, rhythms, and timbres. When a signal is exaggerated it’s more robust and able to withstand passing down from generation to generation. Music is exaggerated in the way infant-directed speech is exaggerated. When talking to a young child, you don’t say, “Look at the ball” you say, “Look at the baaalllll!!!” because it’s easier for the infant to track what is going on with that exaggerated prosody.

Music is easier to track and so its message or melody stays intact better than speech when it is shared. It’s one reason why the Old Testament was committed to music before it was committed to writing. For a couple of thousand years at least, it was only sung and, scholars believe, quite well preserved.

The brain evolved in an interesting way as reptiles became mammals and some mammals became primates and some primates became humans. Layers were added to our core brain area, built out like the rings of a tree trunk. In fact the word “cortex,” which is used to refer to the outermost layer of our brain, means “bark” in Greek. And so we think of ourselves as a very sophisticated species, but it’s all built on this core of a reptilian brain, which is in charge of the most fundamental and basic aspects of being alive. Music activates the reptilian brain and that suggests to me that it has some ancient evolutionary quality, but we don’t know for sure.

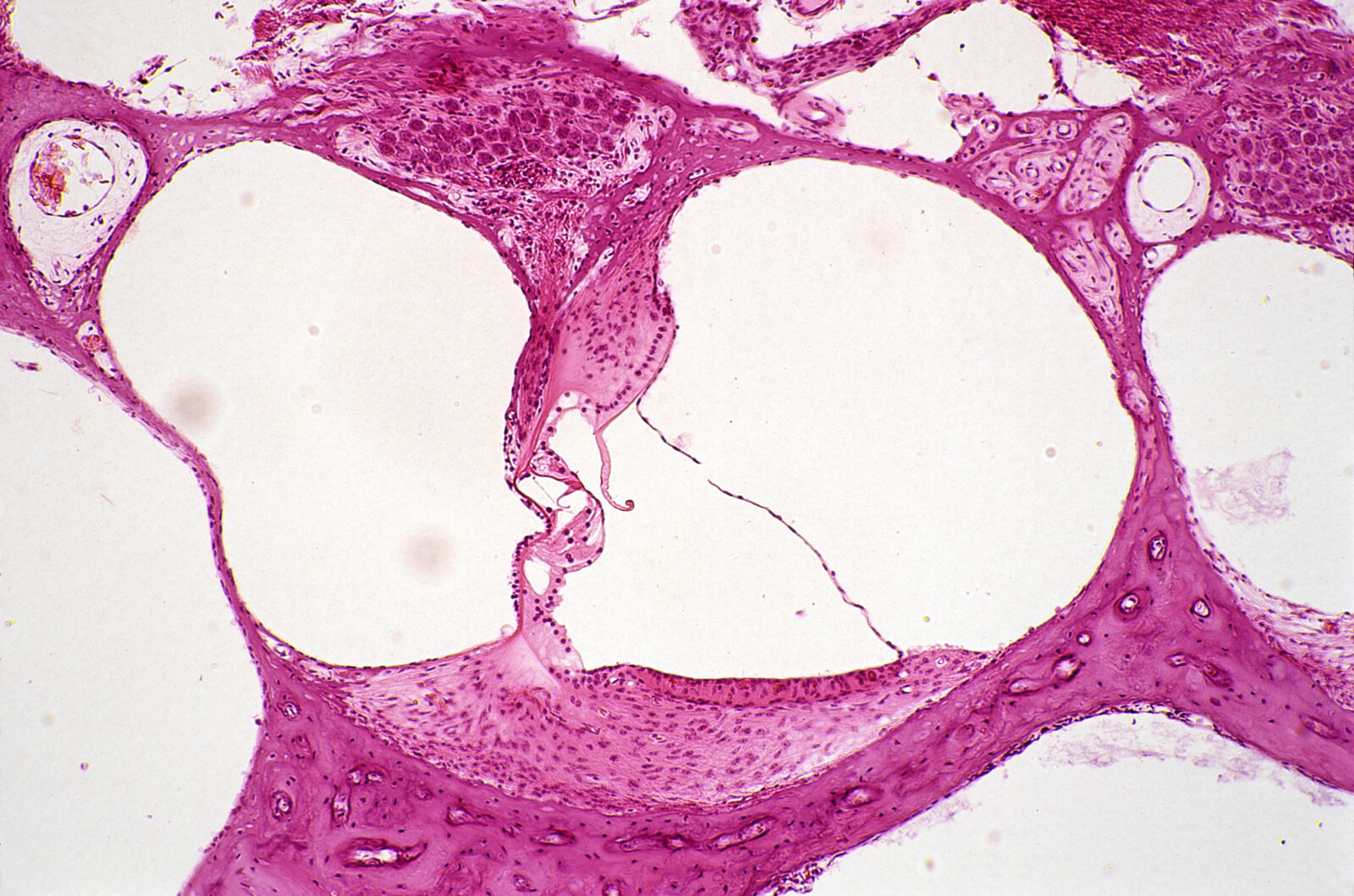

Inner ear (50X magnification). © Ed Reschke/Getty

There’s no scientific answer and no neural answer because it’s a continuum. What sounds like music to one person may sound like noise to another. In effect there’s no scientific definition, but rather it’s in the ear of the beholder. There are circuits in the brain that respond differently to music than to language. For my purposes as a researcher, I’m willing to accept anything somebody says is music as music. I don’t want to exclude something due to snobbery or ethnocentrism or my own taste. For instance, although I don’t particularly care for atonal music, a lot of people like it. And so, if I want to understand how the human brain reacts to music, I have to include that. I keep coming back to the definition of music by composer Edgar Varèse: “Music is organized ” sound.”

Sting came into the laboratory and he composed in the scanner. What we found was really interesting. The gist of it is that he used a lot of the visual cortex when he was composing. I asked him about it and he says that when he’s composing he thinks of songs like architecture with buttresses and filigrees and supports—it’s a very visual metaphor for him. In one experiment we had him imagine ten songs that he knew well, and then we played him those songs and compared the activation. It was strikingly similar. That tells us that when we are mentally imagining or composing music (or at least when Sting is), we’re playing the songs back inside our heads, using the same circuits that would be activated if the music came from outside our heads.

Music can convey our emotional states better than language can, because our emotional states tend to be mixtures of different things. We’re rarely just purely happy or purely sad. There’s always a mixture. The complexity of music allows it to convey that better than language.

Music can modulate serotonin and dopamine reliably. Your brain is producing them all the time, but the amount is up for grabs. Dopamine is involved in feelings of reward when it is present in certain parts of the brain but it’s also involved in helping you to pay attention when it’s in other parts of the brain. Serotonin is a well-known correlate of mood. That’s why we have a whole class of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (antidepressants) that slow down the absorption of serotonin so that whatever your brain is producing tends to stick around for a while. It puts people in a better or less slothful mood.

Prolactin is a soothing, comforting hormone. It’s released when mothers nurse their infants by both the mother and the child. It’s calming. It’s also released when we listen to calming music. I can’t tell you what music to put on that will do that for you because what one person finds calming another person might find aggravating or stimulating. It’s very subjective. For a lot of people, a calming song might be Joni Mitchell’s “Blue” but not for everybody (and not for Joni).

Moods to a neuroscientist are just neurochemical states. We talk about happy or sad or lustful or sleepy as moods, but they are neurochemical states. Our chemistry can put us into those moods based on events. You hear some bad news, it alters your brain neurochemistry, and that puts you in a bad mood. Unless it’s bad news about someone you hate and then it’s schadenfreude.

Clinicians who are part of the American Association of Music Therapists prescribe music for certain outcomes. The issue is that there is no one piece they prescribe to everybody. They have to work carefully with the patient in order to find the right music.

There was a study done where people about to undergo surgery were given either valium or soothing music. The patients who listened to the music did better than the medicated patients on a number of measures. But there’s a whole host of literature that shows that the soothing music must be determined by the patient rather than the doctor.

I did. I think of DJs as musicians. Even if they don’t play an instrument or write music, they are manipulating mood, which is what composers and musicians try to do. They are doing it in often nuanced and skilled ways that cause you as a listener to detect patterns or make connections in music you might not otherwise have made.

Of course there’s also The Smiths’s “Hang the DJ.” But I do think music can save a life, showing us what’s beautiful about the world and helping us feel more connected to our true selves. It can also make us feel more connected to others. Music and all the arts—dance, sculpture, painting, literature—can help us see things from a perspective that we hadn’t seen before, see connections between things that we didn’t see connected before, to open our hearts to truths that we might not be able to understand logically. If a DJ can play a set of songs that does that for you, then yes, a DJ can save your life.

Daniel Levitin is a neuroscientist and musician who investigates pattern processing in the brain. A professor of psychology, behavioral neuroscience, and music at McGill University, Levitin has served as a consultant for the United States Navy, a producer and audio engineer for artists as varied as Stevie Wonder and Blue Oyster Cult, and the best-selling author of This Is Your Brain on Music, The World in Six Songs, and The Organized Mind.

Get the latest news and stories from the Rubin, plus occasional information on how to support our work.