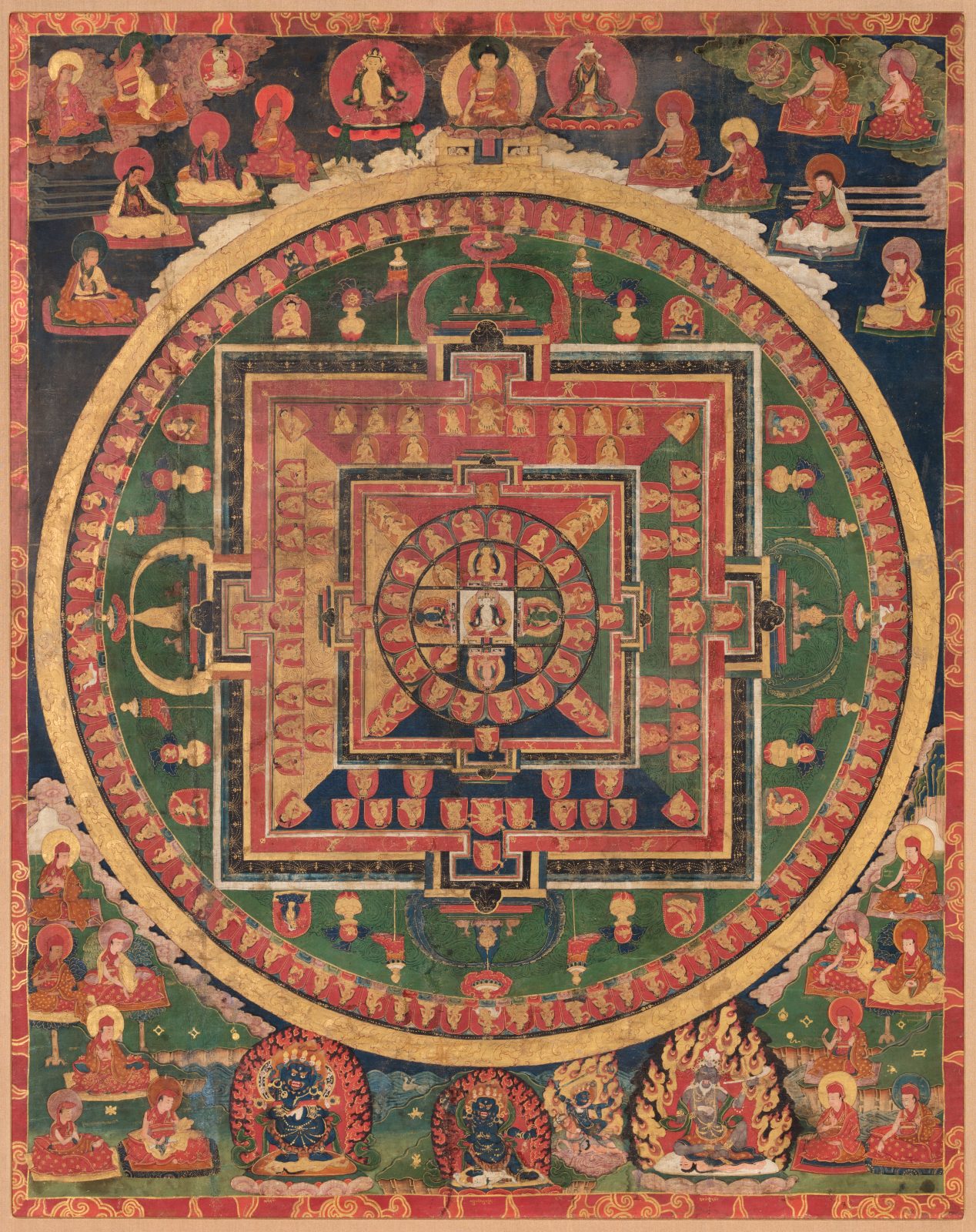

A mandala illustrates the structure of our world, outer and inner, including the five directions, five elements (space, water, earth, fire, air), five aggregates (matter, sensation, perception, volition, consciousness), five inner negativities (ignorance, anger, pride, desire, and jealousy) and their opposites, the five wisdoms of an enlightened mind. The colors of the sections follow the symbolism outlined in the yoga tantras, with blue in the east (where the meditator enters), yellow in the south, red in the west, and green in the north.

The mandala not only shows the outer cosmic and inner psychic universe but also reveals the path to an exalted state, to the inherent buddhahood that slumbers within every being, waiting to be discovered and awakened. The ultimate essence or unifying principle represented in the form of the central deity symbolizes this perfect world.

All painted mandalas are a blueprint of a three-dimensional reality. In this mandala, Vairochana sits on a small cube atop a larger cube, which rests on a crossed vajra. One must imagine the spokes of the vajra protruding from the four sides of the large cube, along with steep stairs—usually not depicted in a painted mandala—leading to the lower cube’s platform. Here one enters the mandala palace through the east gate, which is protected by guardian deities. Inside, deities sit on two pedestals.