Riti Maharjan; The Symmetrical Journey; 2022–2023; acrylic on canvas; image courtesy of the artist

Riti Maharjan; The Symmetrical Journey; 2022–2023; acrylic on canvas; image courtesy of the artist

The French author Anaïs Nin wrote that great art is “born of great terrors, great loneliness, great inhibitions, instabilities.” The Nepal Civil War, which raged from 1996 to 2006, led to the deaths of over 17,000 people. The war maimed over 8,000 men, women, and children, and an additional 1,530 disappeared. These bellicose times changed Nepal forever and led to a mass exodus of men who sought to escape recruitment in the Maoist army and the spiral of violence that had gripped the countryside.

The war also impacted the arts; artists, poets, and writers metamorphosed into activists, articulating the pain and trauma of these times. Local art institutions and theaters were pivotal in reaching the public with powerful stories that documented the horror of the war and the need to lobby for peace.

The 1990s thus marked an era in Nepal when artists began to address the realpolitik of the nation by creating socially aware works that reflected and explored multiple sociopolitical issues. These issues included climate grief, the crisis of the subaltern, the suppression of the disenfranchised, historical grievances of indigenous people, the status of women, gender and LGBTQIA+ rights, the city as a locus for creativity, and the plight of Nepali migrant workers.

At a global level, the plight of the migrant worker is one of both peril and of economic upliftment. Over the last twenty-seven years, political turmoil, scarce local job opportunities, low wages, poor economic growth, social inequality, and natural disasters like earthquakes and the COVID-19 pandemic have propelled an exodus of Nepalis from the country.

While looking for foreign employment and better pay, many Nepalis have encountered exploitation and abuse. Nepali migrant workers have been killed in the unrest and wars in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Israel. In a bid for a better life, Nepalis have also joined armed outfits in Russia and Ukraine and have perished on foreign soil.

The artist Nhooja Tuladhar’s video installation Nepalis Killed in Iraq: A Documentary of Memories is a visual narrative of the lives of the twelve Nepali laborers who were killed in 2004 by Iraqi militants and the political and religious unrest that followed in the aftermath of their horrific deaths.

Nhooja Tuladhar; Nepalis Killed in Iraq: A Documentary of Memories; 2012; video installation; image courtesy of the artist

Yet international labor migration has grown exponentially over the past decade. According to Nepal’s Foreign Employment Promotion Board (FEPB), around 1,700 Nepalis leave the country each day, sending their income back to families they left behind. According to the World Bank, remittance to Nepal is one of the highest in the world and amounts to nearly thirty percent of its GDP. The remittances sent by migrant laborers have helped alleviate poverty among migrant families and improved their living conditions.

The subject of migration is one of paradoxes, as the flight of the youth is causing a demographic imbalance, which has impacted Nepal’s socioeconomic growth and obstructed the nation’s development endeavors. In a nation where over sixty percent of the population is engaged in agriculture, the countryside is now bereft of young men and women, farms are now fallow, and food insecurity is a looming threat.

The printmaker Nabina Sunuwar addresses this issue of fallow farmlands from her home in Okhaldhunga. Her bucolic memories of things past are rooted in her village. These memories continue to make her nostalgic about her family, the sights, sounds, open spaces, and the earthy smell of the village. Her works are evocative of the past, and her imagery oscillates between visible, clear, blurred, and invisible.

Nabina Sunuwar; Echoes from the Land of Memory; 2022; relief print; image courtesy of the artist

Nabina Sunuwar; Echoes from the Land of Memory II; 2022; relief print; image courtesy of the artist

Another facet of this paradox is the social and psychological impact it has on families—the challenges that children encounter growing up without one or both parents and the hardships faced by the elderly as they are deprived of essential care and support. Furthermore, the cultural impact of this exodus is that a generation of young men and women will not be prepared to become the custodians of their culture.

In their short film Dadyaa: The Woodpeckers of Rotha, Pooja Gurung and Bibhushan Basnet tell the story of an old couple in the picturesque village of Jumla trying to cope with all their sons leaving home. In what is an ancient tradition in their village, the parents carve wooden sculptures to represent their sons. Eventually, the viewer is confronted with the moving specter of a wooden family that the couple desperately seeks to activate as living family members.

Pooja Gurung and Bibhushan Basnet; Dadyaa: The Woodpeckers of Rotha; 2016; film; image courtesy of the artists

Pooja Gurung and Bibhushan Basnet; Dadyaa: The Woodpeckers of Rotha; 2016; film; image courtesy of the artists

The jarring revelation of a deserted village covered with these unsettling wooden figures embodies how gravely migration has affected lives in villages. It forces us to come to terms with the lonesome experiences of those left behind—mostly the children and the elderly.

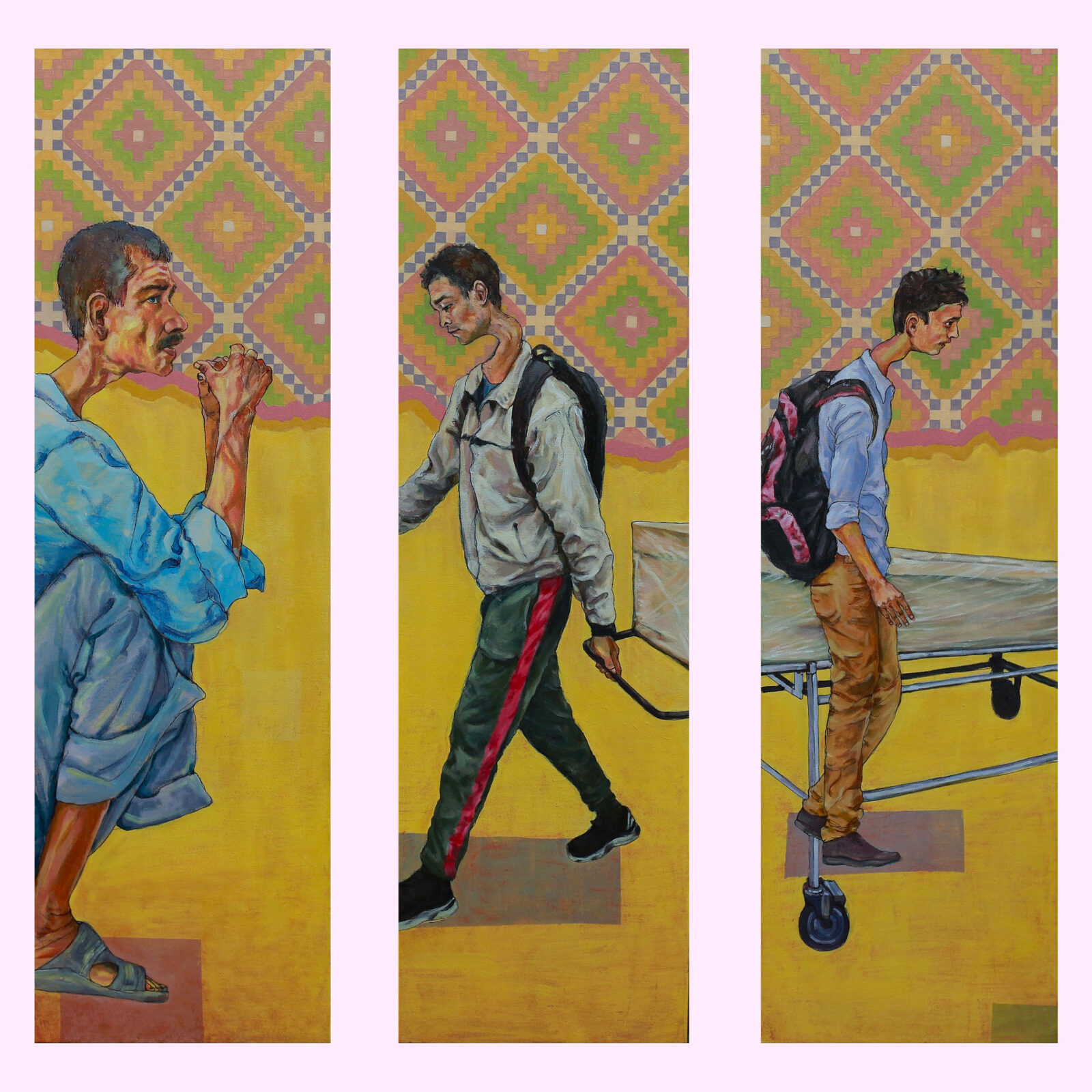

While the artist Riti Maharjan’s works address the pain of families separated from their loved ones, the artist Mekh Limbu has been documenting his personal story. As the son of a migrant laborer, he waited for nineteen years to meet with his father who worked in Qatar and sent remittances back home.

Riti Maharjan; The Shape of Tear; 2022–2023; acrylic on canvas; image courtesy of the artist

Riti Maharjan; My Father’s Hat; 2022–2023; acrylic on canvas; image courtesy of the artist

Mekh Limbu; Parallel Life of a Nepalese Migrant Worker and His Family in Nepal; 2017; acrylic on canvas; image courtesy of the artist

Sadly, migrant laborers are often subject to exploitation—abuse, slavery, and untimely deaths are common among migrant workers from Nepal. FEPB estimates 726 migrants perished overseas in 2012, an increase of eleven percent over deaths in 2011. Contrary to these nationally accepted figures, the advocacy group Pravasi Nepali Coordination Committee (PNCC) claims the real death toll to be around an astounding 1,300 people. Incidentally, the number of deaths among Nepali migrant workers remains the highest among Asian countries. Migrant workers from the cold climes of the Himalayas suffer the early onset of kidney damage due to dehydration from the brutal heat of the Gulf countries.

To document the pain of migrant laborers, artist Sunil Sigdel created an installation titled Spine. His process involved collecting two hundred pairs of used gloves that Nepali migrant laborers had worn on construction sites in India. The artist did not sanitize or rework the gloves, as he wanted to preserve the authenticity of the laborers’ sweat and labor. These gloves were strung together to resemble a monumental human spine—where the medium itself was imbued with the message. The result was an ambiguous object that had a life of its own. The gloves serve as a reminder of the laborers and a profound reference to the working class and their struggles.

Sunil Sigdel; Spine; 2010, 2012, 2014; used gloves, metal hangers pipe light; image courtesy of the artist

Sunil Sigdel; Spine; 2010, 2012, 2014; used gloves, metal hangers, pipe light; image courtesy of the artist

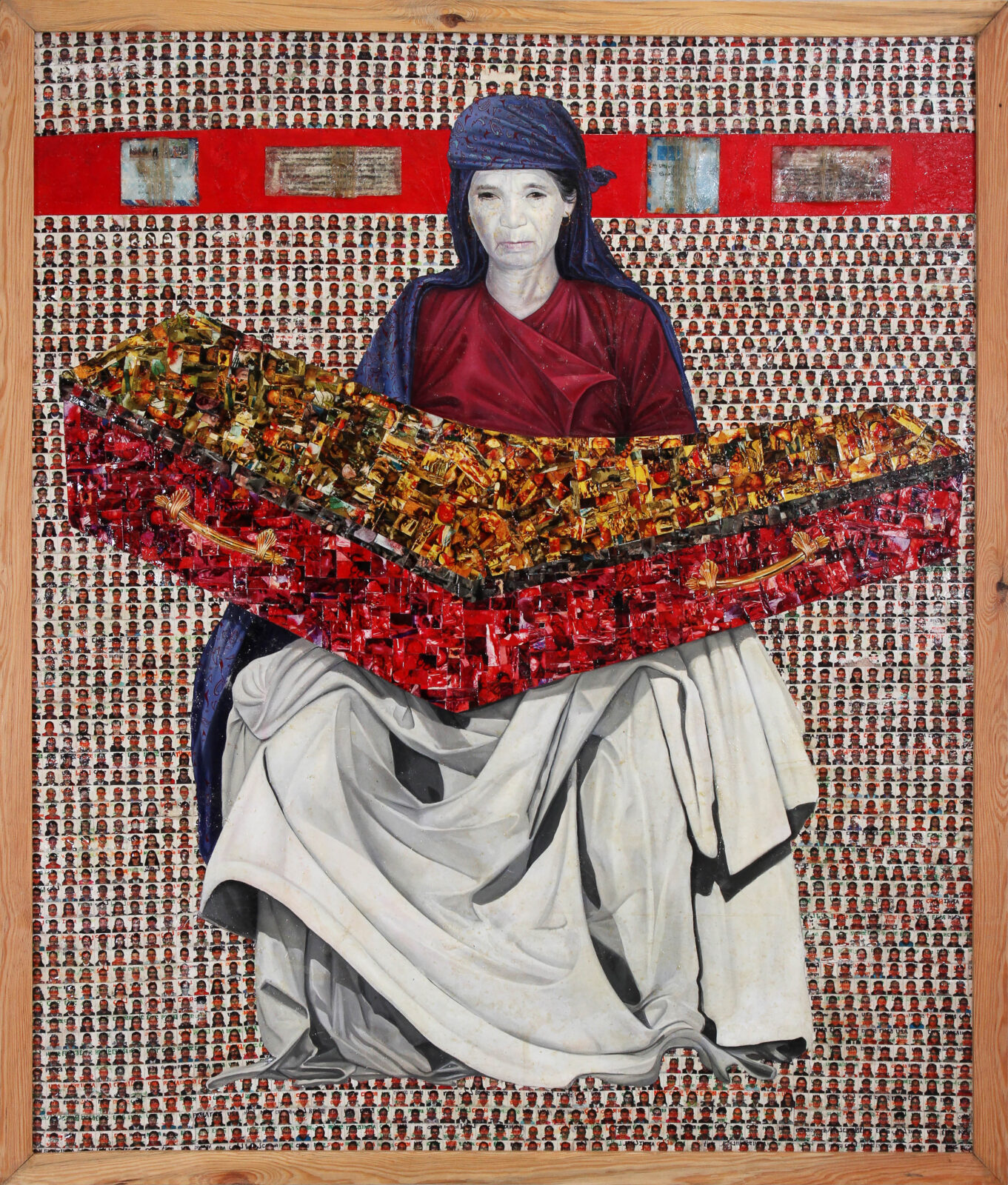

The artist Hitman Gurung is well known for his powerful sociopolitical works. His paintings have drawn attention to the corruption in the country and to the plight of migrant workers, a topic that he has been passionately documenting over the last three years. It is also a personal topic for the artist, as the Gurungs, as with some other Nepali ethnic groups, have a long history of joining foreign armies. Hitman himself had been pressured by his family to work abroad.

Hitman Gurung; Everyday at the Airport from the series I Have to Feed Myself, My Family and My Country; 2013; specific installation with coffin boxes from Saudi Arabia, set of a migrant worker’s uniform from Qatar; imitation gold leaf, print transfer from newspaper, drawing on light box, arduino; image courtesy of the artist

Hitman uses photography to help narrate his sociopolitical concerns. He says, “For me, different genres of art, material, and medium have their own characteristics and essence. In the process of my work, I chose the genre that relates to my concept the most. I have used photographs with different approaches such as photo collage, photo montage, and installation, and I also have merged it with other mediums of art.”

Migrants dream of a better life. However, some never return from working towards this dream. Depending on the company that employs them, it can take up to three years for a dead body to be sent back to Nepal. Still, three to four coffins arrive at Nepal’s international airport each day. Hitman’s art piece Everyday at the Airport features a coffin sourced from a crematorium that was used to bring back the body of a migrant laborer. This work is part of a powerful, larger body of work, I Have to Feed Myself, My Family, and My Country.

Hitman Gurung; Mom Has a Tragic Story from the series I Have to Feed Myself, My Family and My Country; 2014; mixed media; image courtesy of the artist

In multicultural Nepal, divergent yet vigorous last rites are observed. For workers who pass away abroad, such considerations are never made. Their backgrounds are ignored, and their identities are reduced to the contents of a wooden box. The interior of the installed coffin in this artwork is painstakingly lined with a selection of photographs of men and women who applied for work visas.

Their nameless portraits and identities are obscured by calligraphy, which highlights the destinations of the migrant laborers. This information is handwritten in the language of that country and is strategically placed on their forehead or cranial space. The country of origin of the migrant laborer, Nepal, is written in bold Nepali. This text occupies the middle or the heart of the portrait, while the place of birth of each person appears on the bottom half of the photograph, as if to signify that this place is where all hopes and dreams are born.

Each of the photographs has been painstakingly collected, cut, pasted, written upon, and laminated with fiberglass, charting a singular and a national narrative. The exterior of the coffin features tiny prints of passports belonging to the same people. A distorted map of the world hand-drawn in red by the artist highlights the countries where large numbers of Nepali workers have perished.

The Belongings installation is a grim recreation of a dead migrant worker’s belongings returned along with their body. The artist displays the objects as they would arrive in Nepal in boxes containing the deceased’s minimal possessions: passport, ID card, wristwatch, mobile, wallet with photographs of family, diary, clothes, and shoes. The coffin installation reflects the hopes and aspirations of migrant workers as well as the grief experienced by families of those who never return.

Another work, titled 9:11 a.m., is also from the series I Have to Feed Myself, My Family, and My Country. The painting refers to the time difference between Nepal and Qatar, which is two hours and forty-five minutes. When the first massive earthquake hit Nepal in 2015, it was 11:56 a.m. in Nepal and 9:11 a.m. in Qatar.

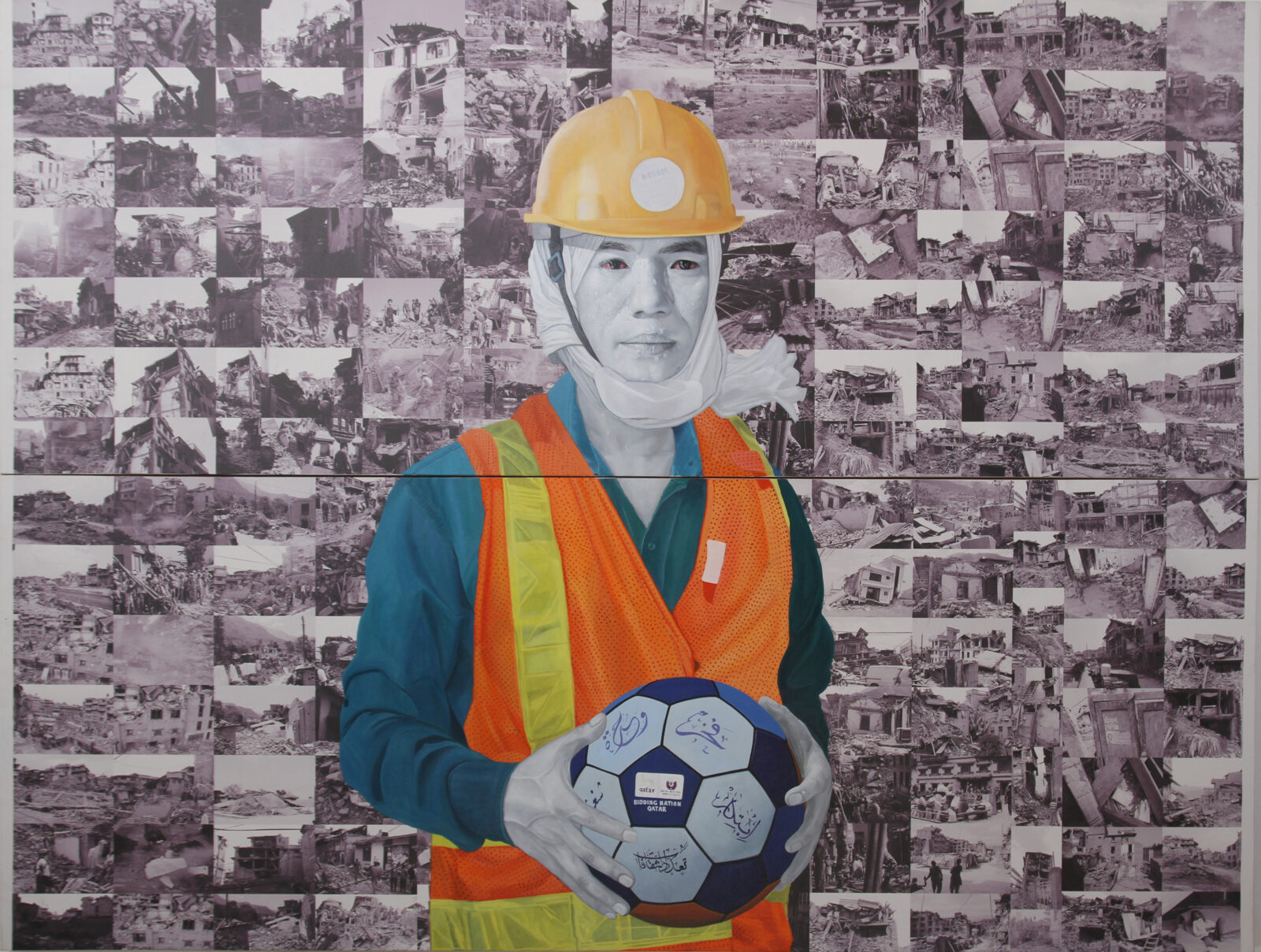

Hitman Gurung; 9:11 am from the series I Have to Feed Myself, My Family and My Country; 2015; mixed media; image courtesy of the artist

On April 25, 2015, and May 12, 2015, two earthquakes struck the Central Region of Nepal. 8,969 people lost their lives, 500,000 homes were destroyed, and more than a million people were displaced. Some communities and localities in particular suffered considerable loss of life and property.

Half a million Nepalese migrants were working and living in Qatar at the time, with many involved in building structures for the 2022 World Cup. Many migrant workers lost their loved ones and their property in the earthquakes and the three hundred aftershocks. Some were traumatized to learn that their entire village had been leveled. But even in this time of emergency, massive loss, trauma, insecurity, and panic, these migrants were not allowed to return to their country. Nepal was in desperate need of help. Hundreds of lives could have been saved in Nepal had there been enough manpower on the ground. The irony is that these grief-stricken migrant laborers were instead working to build the ultra-luxurious stadium for the World Cup.

To narrate this bitter and tragic story, Hitman uses multiple photographic images of the devastation caused by the earthquake that he scanned and digitally printed in black and white on canvas. These stark photographs expose a backdrop of devastation and tragedy while also paying homage to the dead and the resilience of the Nepali people. Against this narrative of sorrow is a self-portrait of the artist standing at the center of the maelstrom.

Dressed as a construction worker, the artist visually relives the agony of the Nepalis working in Qatar. Though his hands and face are deliberately rendered in black and white, in acknowledgement of the devastation captured in black and white in the background, the artist’s eyes are red-rimmed with grief, further unsettling the viewer. The black-and-white portrait of the artist is in stark contrast to his work uniform: the hard yellow hat, blue shirt, fluorescent vest, and most importantly, the football with the logo of the World Cup 2022, which is symbolic of the blood, sweat, and tears shed by Nepalis to bring home money.

Ashmina Ranjit’s work Migration—Space and Dreams is another compelling installation that reflects the perils of thousands of migrants who leave Nepal to find work. Ranjit’s piece features a two-dimensional image of a bunkbed created by the merging of lines of tape on the wall. On the walls above and in between the beds is a montage of precious visual ephemera—images of deities, photographs of family members, and a calendar marking the festivals that migrants will miss and their date of return. These visuals of festivals, historical events, and family are jumbled like a dreamscape that allows each migrant worker to be transported home to their life back in Nepal as they retire for the night.

Ashmina Ranjit; Migration—Space and Dreams; 2022; video installation with photographs, drawing on the wall with tape; image courtesy of the artist

Various economic, social, and psychological components contribute to Nepal’s multifaceted migration scenario. Comprehending these factors is essential for shaping effective policies and actions that manage migration and safeguard migrants’ well-being. Art has an important role to play in offering a way to move forward.

A poem by a migrant returnee, Dalbir Singh Baraili (translation from Kesang Tseten’s documentary A Migrant Speaks), poignantly captures the ethos of the resilient migrant worker whose toil, blood sweat and tears feeds their families and the nation.

Come to the desert

See how the sun is

See how barren the desert is

Come to the desert

See how the sun is

Don’t expect money growing on trees

Don’t expect money growing on trees

Try to understand how it is to work in the desert

See how barren the desert is

These days the desert sun fears us

Ever since it felt the mountains in our heart

I have room for any amount of love within me

Though we toil here, we remain strangers

Though we toil here, we remain strangers

Listen, dear Nepal is within me

I have room for any amount of love within me

Sangeeta Thapa established the Siddhartha Art Gallery in 1987. She served on the board of the Patan Museum and is a fellow of the De Vos Institute of Arts Management. In 2009, she launched the Kathmandu International Arts Festival (KIAF) as a triannual event that later transitioned into the Kathmandu Triennale. In 2011, Thapa set up the Siddhartha Arts Foundation as a nonprofit organization to manage KIAF and train the next generation of arts managers and leaders. In 2022, Siddhartha Arts Foundation served as co-commissioner of Nepal’s first pavilion at the Venice Biennale. The President of Nepal awarded Thapa the Jana Sewa Prabal medal for her contributions to the field of Nepalese art.

Get the latest news and stories from the Rubin, plus occasional information on how to support our work.