1962 U-2 aerial image of Nartang Monastery before its destruction from the west orientation.

1962 U-2 aerial image of Nartang Monastery before its destruction from the west orientation.

In 1962, a U-2 reconnaissance plane known as “Dragon Lady” took off from a US base in India and headed toward central Tibet. Like many Cold War missions, its objective was to gather intelligence. Equipped with high-resolution cameras, the plane photographed military activity across the Tibetan Plateau. But as it flew over the city of Shigatse and the surrounding region, Dragon Lady captured something else—not military barracks or machinery, but Nartang Monastery, one of Tibet’s most important cultural and religious campuses.

For over 700 years, the Monastery had been a center for religious education, practice, and early scriptural production. It housed over 100,000 hand-carved woodblocks and one of the region’s largest printing presses. Taken at a ground resolution of one to two feet, Dragon Lady’s photographs capture the grandeur of the complex in detail. The shadows, stupas, and roofs appear in vivid clarity. These are among the last known images of the site. Just five years later, the Monastery was reduced to rubble.

Nartang Monastery is just one of an estimated 2,000 to 6,000 Tibetan Buddhist monasteries that were destroyed in the 1950s through 1970s, following China’s annexation of Tibet and during the Cultural Revolution. As historic centers of religious and social life, the destruction of these sites represents a profound loss of built heritage across the cultural landscape of Tibet.

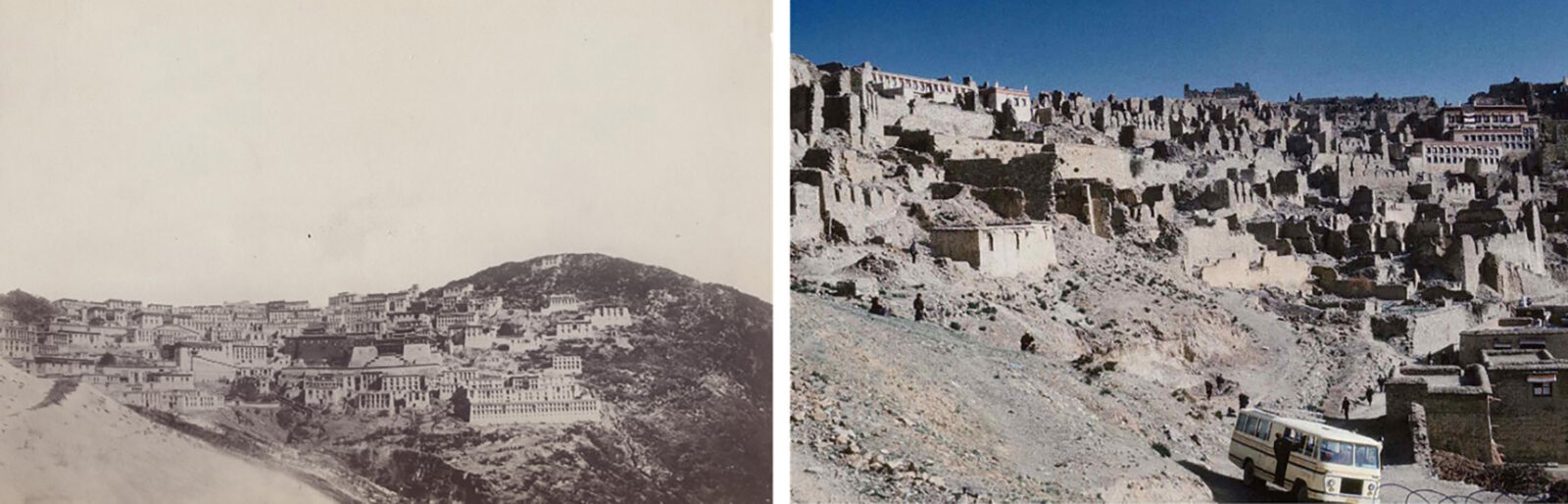

Left: Pre-destruction Ganden Monastery in 1900 (Library of Congress). Right: Post-destruction in 1985 (David Rosberg, 1985).

Nartang was not the only historical site captured on U-2 film. Dragon Lady’s mission was just one of eight that flew over Tibet throughout the 1960s and 1970s, documenting a landscape that was soon to be permanently altered. Similar missions happened across the world, spanning Taiwan to Russia to Cuba.

The CIA classified the film from these missions and kept them under top-secret designation until its declassification in the 1990s. Today, the film cannisters are stored in Kansas and are available for viewing and scanning at the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) cartographic reading room in Maryland.

1962 U-2 aerial image of Nartang Monastery before its destruction from the west orientation.

A-2 camera set being loaded into a U-2 plane in 1956 (US Air Force photo).

As a Tibetan immigrant living in exile and an architect dedicated to cultural preservation, Tenzin Nyandak recognized the U-2 film archive as a powerful tool for uncovering Tibet’s historical built landscape. Nyandak is the founding principal of Studio Nyandak, a multidisciplinary design firm based in New York City, with a pro-bono satellite office of young Tibetan architects and engineers in Dharamsala, India. In collaboration with Dr. Karl Ryavec, a professor of heritage studies and author of A Historical Atlas of Tibet, Nyandak and his team led a yearlong effort to identify historic Tibetan Buddhist monasteries within thousands of U-2 film frames and digitize the imagery for public access.

One of the central challenges of this work—and a major barrier for others using U-2 imagery—is the lack of geographic reference data. Although the images are publicly available and hold extraordinary historical value, they remain largely understudied. When the CIA declassified the film in the 1990s, it did so without providing any metadata to identify where the images were taken. As a result, matching individual frames to specific locations is often seen as prohibitively difficult.

Digital imagery specialist Lin Xu has spent over two decades addressing this problem. His first trip to NARA began with a personal effort to find photos of his hometown, Jilin City, China, which suffered widespread destruction during the Cultural Revolution. Since then, he has developed a method for georeferencing U-2 film and scanning slides at high resolution. Now part of the Tibet from Above team, Xu applies this process to areas in Tibet—recovering visual records of built, vernacular landscapes that people once called home.

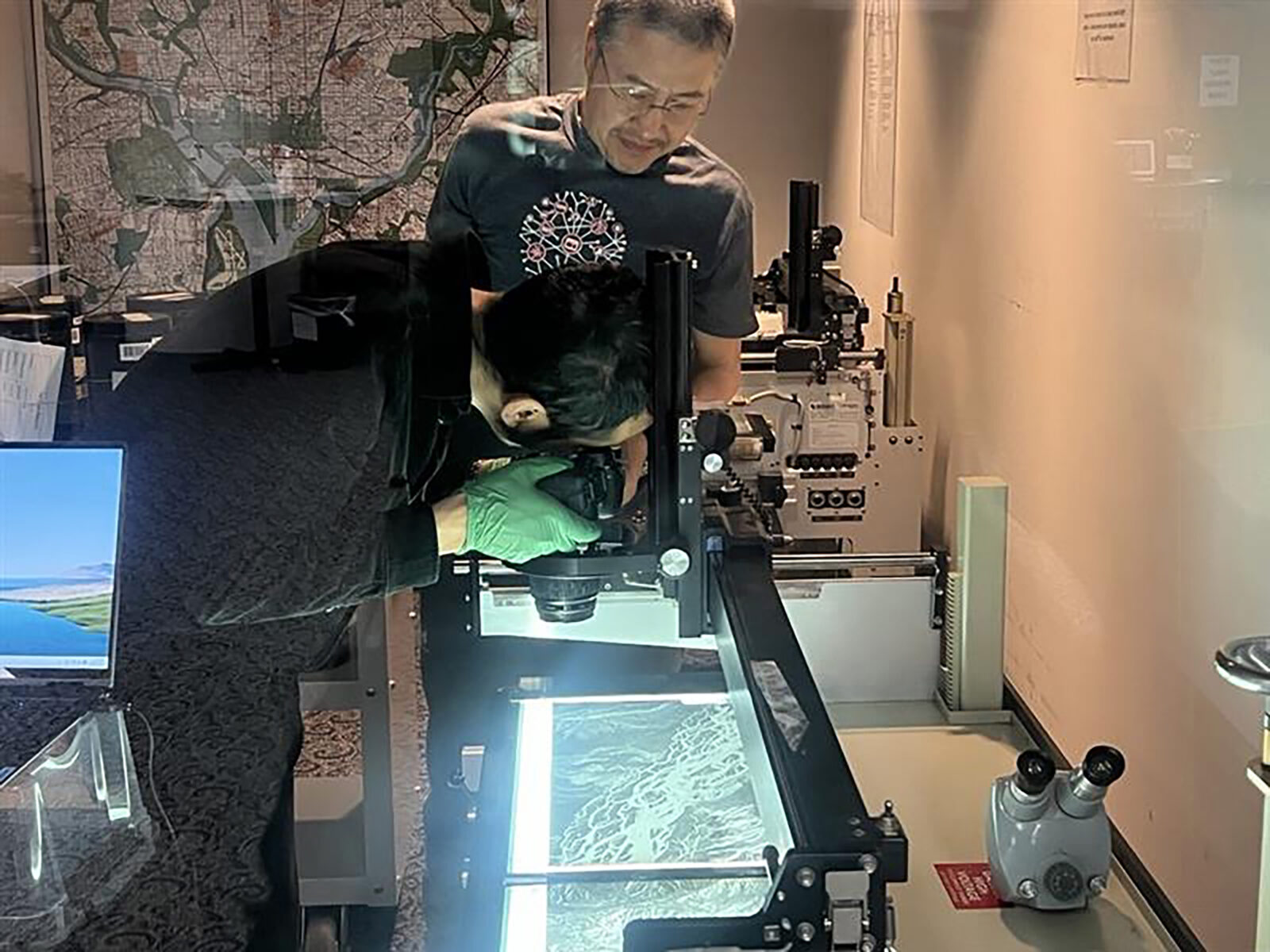

In March 2025, members of Studio Nyandak’s New York team, Karl Ryavec, and Lin Xu travelled to NARA in Maryland to retrieve U-2 film capturing now-destroyed Tibetan Buddhist monasteries. The visit followed two years of extensive preparation. During that time, the team consulted Chinese Gazetteers, studied Tibetan primary texts, and conducted interviews with elder monks living in exile to verify the precise geographic coordinates of more than 2,000 Tibetan Buddhist and Bonpo monasteries destroyed in the latter half of the 20th century. Once the sites were geolocated, the team submitted targeted requests for NARA film rolls believed to contain imagery of the original, intact structures.

The cartographic reading room at NARA opens at 9:00 a.m., but by then researchers, contractors, and scanning equipment have often already formed a long line outside. To stay ahead, Lin Xu made sure the Tibet from Above team arrived before 8:30 a.m. Once inside, researchers work at shared tables with light desks and scanners. Besides a brief break for lunch, most work until the archives close at 5:00 p.m.

Over three days, the team carefully unraveled film rolls by hand and photographed nearly 8,000 images frame-by-frame. Some rolls showed multiple monasteries dotting mountainsides, others only clouds. Each evening, the team uploaded the day’s images and shared them with Studio Nyandak’s Dharamsala office. Thanks to the time difference, the Dharamsala team geolocated each frame using Google Earth and QGIS and created a referenced list of missions and images. The following day, the NARA team scanned these selected monastery frames at a high resolution for later study.

Tibet from Above team members Tenzin Nyandak and Lin Xu scanning U-2 film at the National Archives and Records Administration in Maryland.

The digitized U-2 images highlight the archive’s enormous untapped potential for studying Tibet’s modern history. The detail captured by the high-resolution images reveals both the scale of monastic heritage lost in the late 20th century and inconsistencies between original structures and later Chinese government-led reconstructions. Committed to public access, the project team published the scanned images in Tibet from Above’s online exhibition, where they are available for viewing, download, and research use.

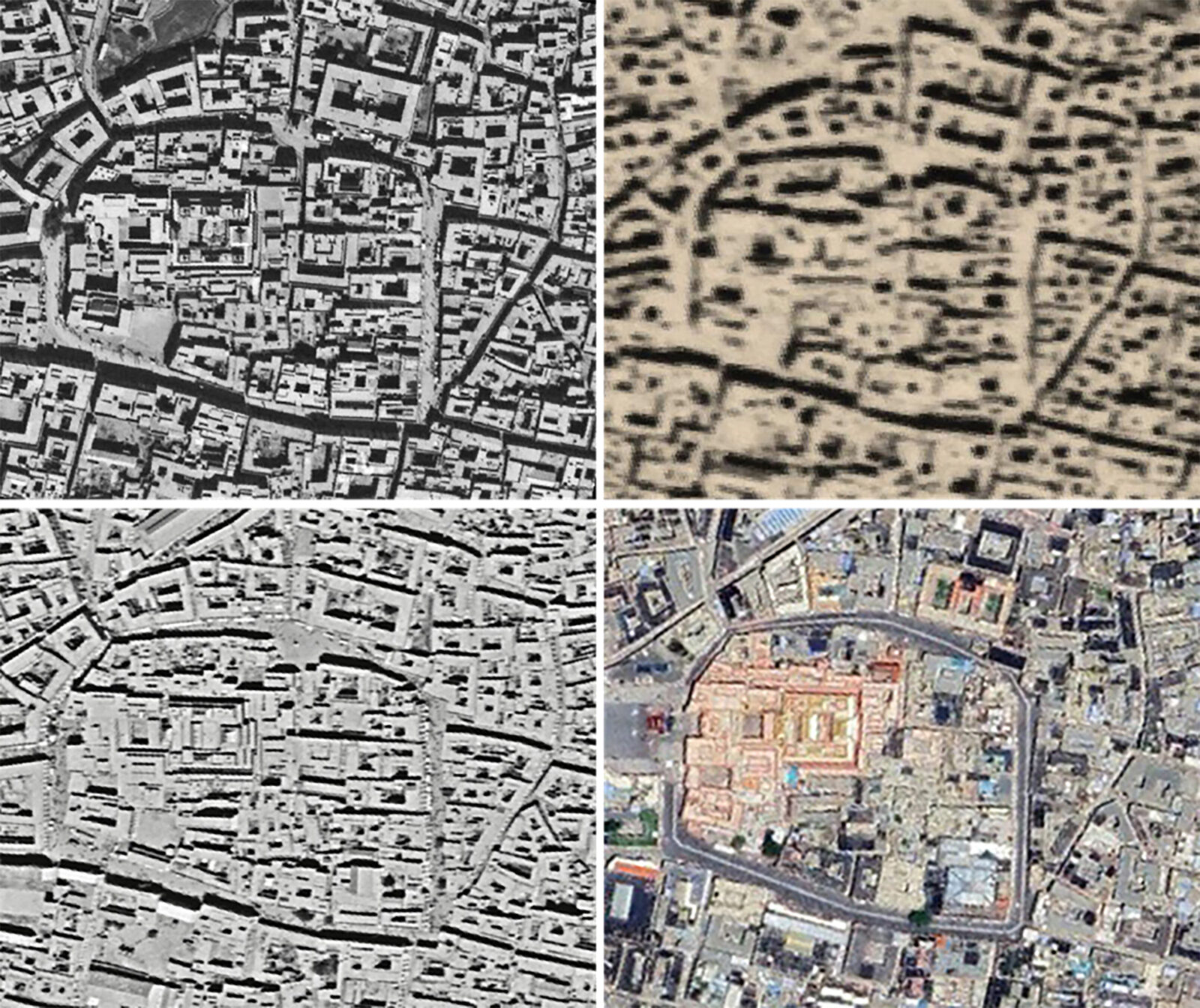

Top left: Aerial photographs of Nartang Monastery, near Shigatse, in 1962 taken by a U-2 Spy Plane. Top right: 1965 Corona Satellite KH-4A. Bottom left: 1975 Hexagon Satellite KH-9. Bottom right: 2025 Landsat Satellite.

Top left: Aerial photographs of Sera Monastery in 1959 taken by a U-2 Spy Plane. Top right: 1968 Corona Satellite KH-4A. Bottom left: 1982 Hexagon Satellite KH-9. Bottom right: 2024 Landsat Satellite.

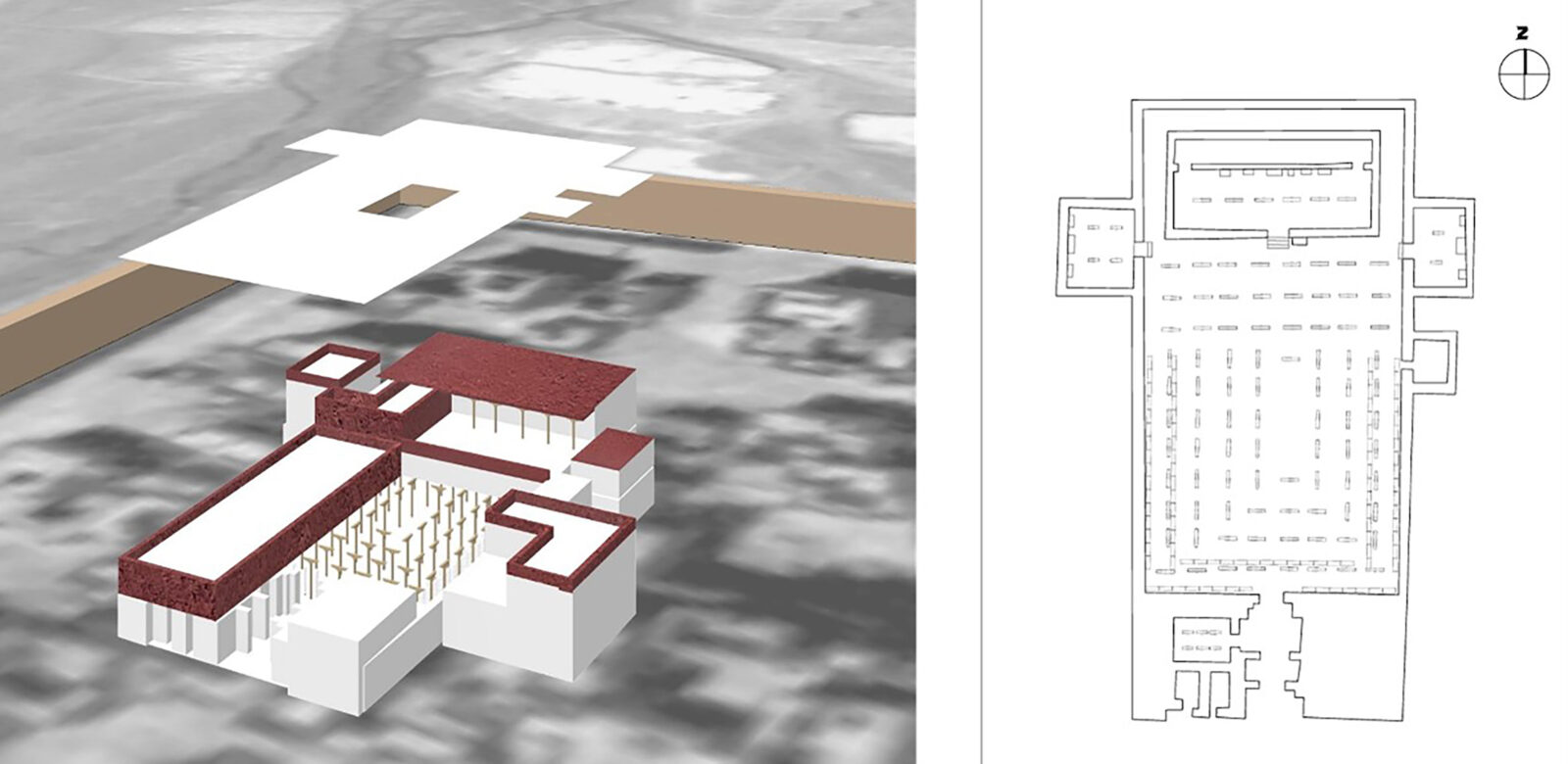

Especially for regions that have suffered widespread upheaval, detailed visual documentation offers displaced peoples a powerful means of remembrance and a foundation for cultural production in exile. Motivated by this goal, the Tibet from Above team has launched a new phase of research. Using the digitized scans, they are applying shadow detection and historically informed architectural stylization to create digital 3D reconstructions of the monasteries. The first of these examples is Nartang, the expansive campus captured by Dragon Lady in 1962.

3D model of Nartang Monastery made by Studio Nyandak, 2025. Studio Nyandak used shadow detection to reconstruct building masses from U-2 imagery and referenced historical research for architectural stylization.

Left: Rendering of Nartang’s Parkhang Chenmo using floor plans made by Chinese archeologist Su Bai in 1959. Right: Pictured floor plan redrawn by authors.

Designed for surveillance during the Cold War, U-2 planes were meant to capture strategic intelligence—not preserve cultural memory. Yet in the process of documenting military targets, they inadvertently recorded vivid traces of landscapes now transformed or lost. While Tibet from Above centers Tibetan Buddhist monasteries, its resulting 8,000 scans offer a foundation for research across fields, including climate history, geography, urbanization, infrastructure development, and much more. The team hopes these images will be used widely and that digitization continues—not only for Tibet but also for other regions with historical landscapes to unearth.

Top left: Aerial photographs of Jokhang and Barkhor in Lhasa, Tibet, in 1959 taken by a U-2 Spy Plane. Top right: 1968 Corona Satellite KH-4A. Bottom left: 982 Hexagon Satellite KH-9. Bottom right: 2024 Landsat Satellite.

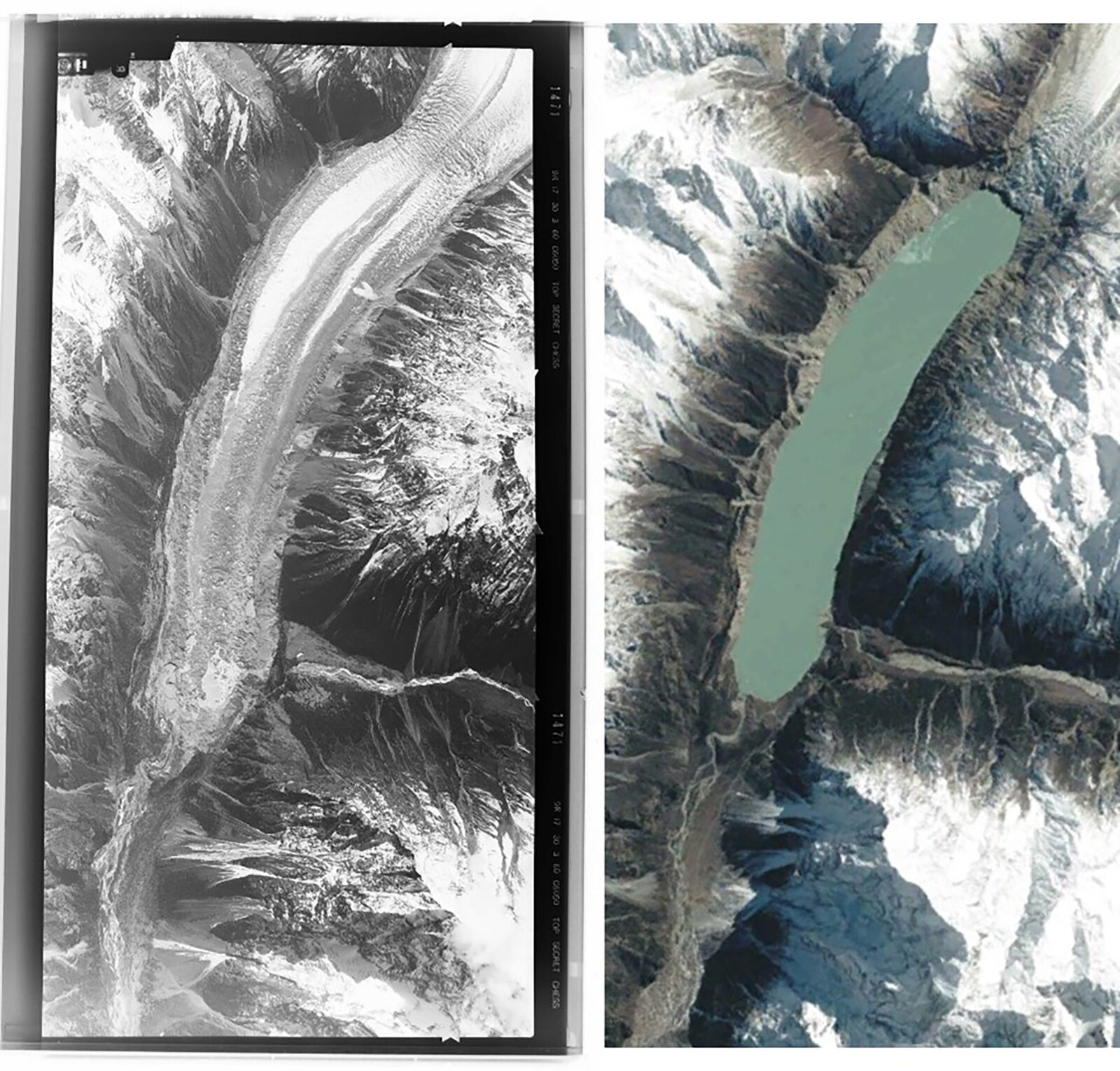

Left: Film negative of a glacier in the Himalayas along the border of Kham and Utsang, Tibet, taken by a U-2 Spy Plane in the 1960s. Right: Photo of the same glacier taken by a Landsat Satellite in 2018.

U-2 image of Mount Kailash, a sacred mountain in Tibet, in 1963.

Tibet from Above was a recipient of a 2024 Rubin x Research grant.

Tenzin Nyandak is the founding principal of Studio Nyandak, a multidisciplinary design practice based in New York City and Dharamsala, India. He is deeply committed to safeguarding cultural heritage, supporting authentic architectural identity, creativity in structural engineering, and supporting the younger generation of architects and engineers. In addition to directing architectural and engineering projects at both offices, Tenzin collaborates with scholars and experts across disciplines on research projects that support the wider field of Tibetan heritage preservation.

Yumtsokyi Bhum helps coordinate Studio Nyandak’s research initiatives, bridging the work of the Dharamsala and NYC offices with broader networks of support, scholarship, and research dissemination. Alongside Studio Nyandak and Dr. Karl Ryavec, Yumtsokyi co-authored “Monastic Architectural Reconstruction From a 1962 U-2 Air Photo of Nartang in Central Tibet,” accepted to be published in the upcoming issue of Studies for Digital Heritage. The article delves into the technical methodology of Tibet from Above’s first digital reconstruction.

Get the latest news and stories from the Rubin, plus occasional information on how to support our work.