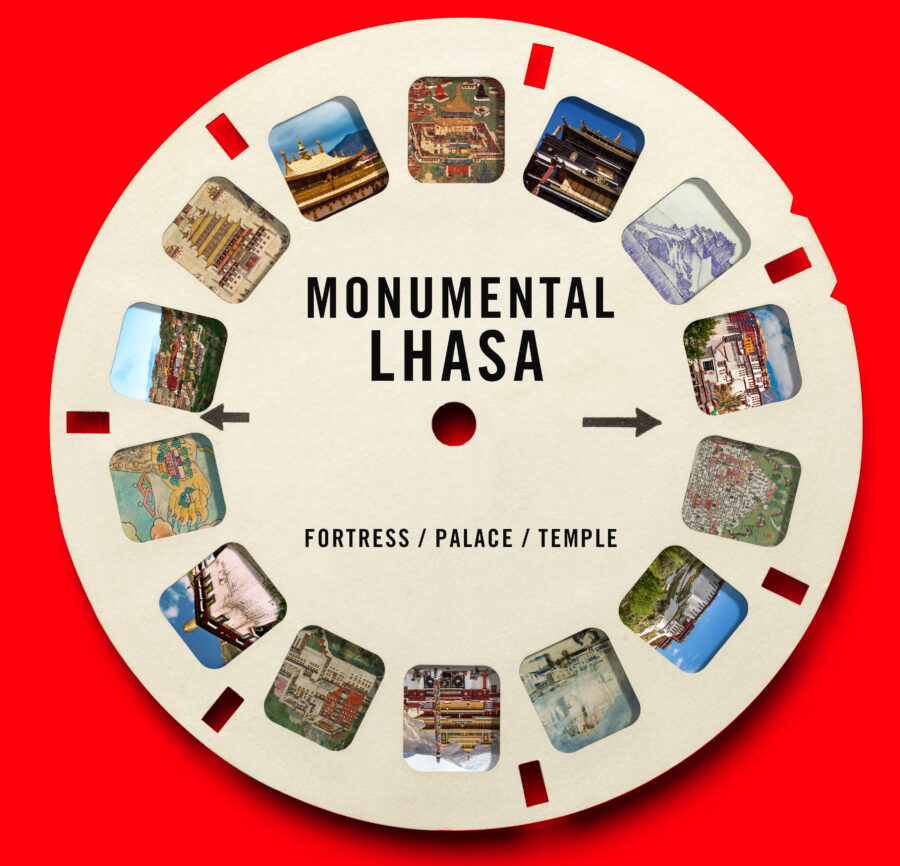

Have you visited the Statue of Liberty in New York City? Have you climbed the Eiffel Tower in Paris or strolled across the smooth marble floors of India’s Taj Mahal? Whether you have stood in front of these global landmarks or not, you are probably familiar with them because you’ve seen their images in newspapers, postcards, and online. These monuments are immediately recognizable around the world because their images are replicated and widely shared, creating opportunities for distant audiences to connect and engage with the monuments via their images.

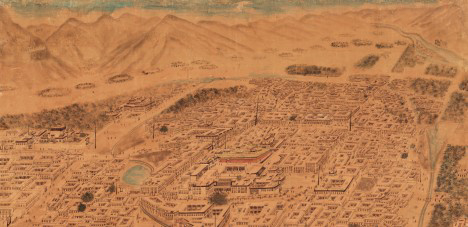

Perspective Map of Lhasa (detail); Lhasa, Tibet; early 20th century (pre-1912); ink, watercolor, and gold leaf on rice paper; Collection of Knud Larsen.